Peter Schrijver

In early August 2023, residents of Russian-annexed Crimea received phone calls containing a recorded message urging them to avoid military infrastructure, naval bases, and assembly areas for military equipment in Crimea. The unidentified speaker warned of missile strikes and ongoing drone attacks against Russian forces. It was yet another example since Russia’s invasion last year of the innovative strategies in the information environment for which Ukraine has earned praise. Specifically, Ukraine has gained admiration for its effective communication of messages to both domestic and international audiences, as well as for its robust cybersecurity measures, which have enabled the prevention of and response to cyberattacks on its networks and systems.

Of course, success in war is often a function not only of innovation, but also of a willingness to borrow tactics, techniques, and procedures that have worked well elsewhere, in other conflicts. Indeed, the phone calls in Crimea bear a resemblance to similar warning calls and text messages received by Israeli citizens and Gaza residents over the past fifteen years during periods of tension between Israel and the de facto rulers of Gaza, Hamas. But this is not the only example that appears to have influenced the development of Ukrainian operations in the information environment. Unsurprisingly, these operations have also borrowed from Soviet and Russian concepts of information warfare. They have also incorporated Western ideas about strategic communications. In some instances, the learning pathways are clear and evident, while in others they are less so. But regardless of how deliberately Ukraine has emulated others’ successful approaches, it is clear that effective practices migrate across both time and geography. Tracing that migration not only enables observers to better understand Ukraine’s operations in the information environment, but also equips them to leverage such migration in future conflicts. For NATO countries, that likely means learning from Ukraine in the same way it has learned from others.

Soviet and Russian Influences

The legacy of Soviet and Russian ideas about information warfare is natural, and Russia, as the dominant state in the Soviet Union, has had a profound and deep influence on Ukraine.

An example can be found in the activities of the Ukrainian military intelligence service, HUR (Holovne Upravlinnja Rozvidky). This service uses intercepted phone calls of Russian soldiers to family members and regularly releases excerpts of these calls on social media. In particular, fragments are used in which Russian soldiers express discontent, disappointment with their leadership, or confessions of (war) crimes. This highlights the twenty-first-century possibilities of technology. However, it is not a new idea to use the personal communication of opponents for influence operations. During the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Red Army’s Political Directorate, responsible for all political propaganda by the military, targeted German army members with specific messaging. After the Battle for Moscow, in December 1941, the directorate started an operation analyzing captured letters from German soldiers to their families. These letters, in which German soldiers expressed dissatisfaction about their circumstances in winter, provided insight into the morale and psychological stamina of the enemy. This information was used to specifically tailor messaging to German forces via a wide array of delivery methods. The themes—You are lost, forgotten, and doomed in an endless Russian winter; The dead are calling to the ones still alive; The ones who surrendered do not suffer anymore—are reminiscent of today’s HUR operations on social media.

Another example is the extensive use of personal celebrity to enhance individual messages. For the Soviet Union, this took the form of employing well-known authors and poets as war correspondents. These prominent writers—like Ilya Ehrenburg, Konstantin Simonov, and Vasilii Grossman, who all wrote for the military newspaper Krasnaia Zvezda—followed Red Army units in their battles against Nazi Germany. Ehrenburg was one of the leading anti-German publicists and became legendary, the single most read journalist of the war, adored by the population. Ukraine has adopted a different approach, but one that still leverages celebrity. Instead of relying on prominent authors with a large, preexisting following, it grants ordinary Ukrainian soldiers the ability to send out a continuous stream of messages on social media about their daily activities on the frontline, giving their audiences an up-close view of the military’s experience. This has made some of them celebrities on TikTok and YouTube, with several—like Lieutenant Olga Bigar (callsign “Witch”) of the Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces and Operator Starsky—attracting large numbers of followers, just as Ehrenburg did eight decades ago.

It is noteworthy that social media publication policies are guided from Kyiv, ensuring that messages revolve around key themes—bravery, resilience, and defiance—and are consistent and aligned with overarching goals. Other than that, Ukrainian content creators hardly face any restrictions, unlike their Soviet predecessors, who operated under harsh guidelines from Moscow. Humorous content and interaction with animals, particularly cats and dogs, are recurring themes in videos of Ukrainian military personnel on social media. Additionally, blatant failures and alleged crimes of Russian armed forces are frequently emphasized.

Ukraine has also adopted—and adapted—more modern Russian ideas, like the concept of information confrontation. Russian military thinking separates this concept into two main categories: informational-psychological confrontation and informational-technical confrontation. The former consists of efforts to influence the enemy’s population and military forces, while the latter involves the physical manipulation or destruction of information networks. According to Russian military doctrine, state actors handle implementing this concept, but nonstate actors also play a key role.

Ukraine has in recent years felt the effects of Russian information confrontation firsthand. Russia ratcheted up a multifaceted campaign of information warfare in 2014 with the intention of undermining Ukrainian sovereignty. This included a range of strategies, including physical acts, online attacks, and efforts to sow disunity in Ukrainian society. Russia specifically attacked the physical and digital information infrastructure of Ukraine. The goal was to weaken Ukraine’s defenses by stimulating reactions like confusion, disorganization, and a sense of helplessness.

Inadvertently, civil society in Ukraine during the years 2014 and 2015 aligned with Russia’s paradigm of information confrontation, which accentuates the involvement of nonstate entities. Nongovernmental organizations and initiatives such as Information Resistance, StopFake.org, Ukraine Today, and the Ukraine Crisis Media Center assumed a critical function in counteracting propaganda and extending media-bolstering efforts. This involved the provision of services conventionally attributed to governmental authorities. Presently, these Ukrainian nongovernmental organizations persist in their consequential roles, wherein they—along with fundraising collectives—continue to have substantial influence on the communication landscape of wartime Ukraine.

After the events of 2014 and 2015 Ukrainian researcher Mikolay Turanskiy described the consequences of Russia’s operations and the necessity to improve his country’s approach. “The establishment of an independent Ukraine has been associated with persistent psychological and informational pressure,” he wrote. “To mitigate the effects of such pressure, Ukrainian scientists, and experts in the field of information and psychological warfare must make concerted efforts to expose manipulative and propagandistic actions and prevent hostile information and psychological campaigns from being conducted on Ukrainian soil.” Concurrent with Turanskiy’s recommendation, Ukraine’s military-scientific establishment studied the Russian approach and developed strategies to counter it. This has led to a series of measures to improve the resilience of Ukraine in the information environment.

Learning from the Israeli Experience?

Despite the combined government and civil society efforts to thwart Russian influence, Ukraine faced a bleak situation after the dust somewhat settled with the Minsk agreements in 2015. Russia had annexed Crimea and an uneasy ceasefire in the east of Ukraine was established. The National Institute for Strategic Studies in Kyiv concluded in a postmortem report that Ukraine had lost the battle in the information environment.

In this respect, Ukraine faced similar challenges as Israel had in the past. This is exemplified by an archetypical event during the Second Lebanon War in 2006. During that war, Hezbollah fired an Iranian-supplied Noor antiship cruise missile at the Israeli corvette INS Hanit. The attack killed four crew members and caused considerable damage to the ship. Although the strike had a minimal impact on Israel’s naval operations, it had a profound psychological effect. Hezbollah used its media platform, al-Manar, to broadcast a video that claimed to show the attack, accompanied by a triumphant speech by Hezbollah’s leader, Saeed Hassan Nasrallah. The video was intended to create a powerful impression on both domestic and international audiences and to achieve several objectives: demonstrate Hezbollah’s capability, emphasize the group’s resolve, and boost its image and legitimacy It was an event that showed Hezbollah’s skillful use of information warfare as a strategic tool and how nonstate actors can challenge state actors in asymmetric conflicts by exploiting their weaknesses. Considering instances like this, analysts credited Hezbollah with a decisive victory in the information environment, which Israel failed to achieve at that time.

However, six years later, in 2012, during Operation Pillar of Defense in Gaza, Israel showcased that it had learned to use the information environment to its own advantage, specifically social media. A central focus of Israel’s social media campaign was the portrayal of the precision and potency of its weaponry, alongside shedding light on the difficulties endured by Israeli citizens in the face of Hamas rocket barrages. A distinct hallmark of Israel’s digital engagement during the operation was its mobilization of domestic and international supporters via platforms such as YouTube, Twitter and Facebook. By disseminating messages and testimonials across online platforms, Israel succeeded in fostering a sense of unity, solidarity, and patriotism among its backers. A distinctive facet of Israel’s social media approach was its decentralized and bottom-up orientation, which included giving young, media-savvy officers of the Israel Defense Forces the lead in the social media campaign.

Both Israel and Ukraine have launched dedicated online ventures tailored to supply their respective supporter bases with resources for information dissemination and advocacy. An example of this transpired in the initiation of the Israel Under Fire project on social media in 2012. This citizen initiative, reinforced by government endorsement, provided live updates and information about attacks on Israel. The campaign aimed to raise awareness and support for Israel’s right to defend itself. Ukraine has embraced comparable tactics, shaping platforms and campaigns to not only diffuse accurate information but also to rectify any misinformation, while concurrently fostering international awareness of the circumstances faced by Ukraine, its military, and its people. An example is #SnakeIslandStrong, a campaign designed to spotlight the valor and tenacity exhibited by Ukrainian soldiers during their defense of Snake Island against a Russian attack in 2022. Additionally, Ukraine’s adept use of social media to express gratitude toward international partners for their (military) aid packages further illustrates its strategic approach to fostering support and solidarity.

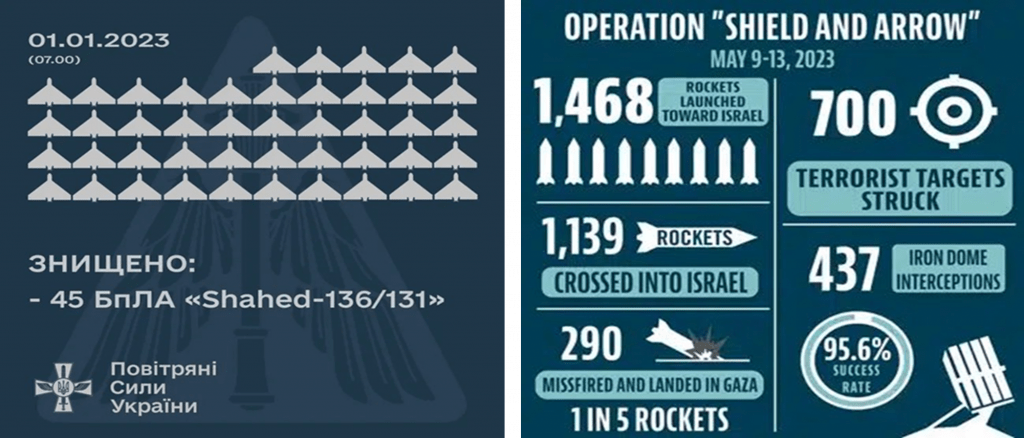

Two examples showing the similarities between visual overviews of successful air defense operations shared on social media by the Ukrainian Armed Forces (left) and the Israel Defence Forces (right).

Although there is no record of official contact between Ukraine and Israel regarding an exchange of knowledge on operations in the information environment, there are more than just superficial similarities between the approaches of the two countries. Both nations have rallied domestic and international support by capitalizing on the reach of social media. Furthermore, Ukraine has extended beyond this trajectory by incorporating initiatives for crowdfunding goods for the army and the needs of citizens who are not able to help themselves, thereby broadening the scope of engagement. A notable case in point is the recent crowdfunding effort undertaken by several Ukrainian entities—the government program United24, nongovernmental organization Come Back Alive, and private company Monobank. This cooperative initiative, aimed at procuring ten thousand first-person-view drones and ammunition for Ukrainian forces, emerged as an illustrative instance of mobilizing financial support from the public. Within a span of five days in August 2023 the crowdfunding organization collected 235 million Ukrainian hryvnia, equivalent to 6.3 million US dollars, through contributions from over three hundred thousand individuals and companies from Ukraine and abroad.

The Israel Defense Forces, and Israel’s broader experience more than ten years ago, demonstrated that combat operations, coordinated with activities in the information environment, can have significant impacts. Like Ukraine in 2014, Israel had learned from a previous situation (the Second Lebanon War in 2006) that a compelling narrative is required, one that explains why its forces were on the battlefield and solidifies support from its own population and foreign sympathizers. After the experiences of 2014 and 2015, the Ukrainians seem to have taken these lessons to heart and are applying it in their ongoing operations.

Strategic Communications as an Integrator—Facilitated by Ukrainian Networks

A third apparent external influence on the Ukrainian approach to operations in the information environment is the NATO strategic communications concept. In 2014, a report from the National Institute for Strategic Studies in Kyiv recognized the active role of civil society in countering Russian influence, while at the same time noting that this positive development was set against the backdrop of the government’s tame media response toward the Russian campaign. The institute’s experts attributed this to the absence of a solid national strategy for sharing information with both local and international audiences. There was also a shortage of resources and skilled personnel in this area.

Given these challenges, the report’s authors advised that it was necessary to “implement and institutionalize the practice of the strategic communications”. This idea gained more traction as time went on. Ukrainian scholars Tetiana Popova and Volodymyr Lipkan outlined the core features of this concept as a coordinated effort involving both state and nonstate actors to manage information, including by using various methods to shape public opinion, safeguard information sovereignty, and advance national identity and interests.

In 2015 Ukraine teamed up with NATO. This collaboration resulted in the NATO-Ukraine Strategic Communications Partnership Roadmap. The roadmap, signed by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council Secretary Oleksandr Turchynov, aimed to boost Ukraine’s strategic communications abilities. It also sought to cultivate a culture of strategic communications in Ukraine and maintain standards of accuracy and ethics to ensure the credibility of government communication.

An important aspect of Ukraine’s strategic communications culture is the strong ties among specialists from various departments in charge of information-related tasks in Ukraine’s ministries and civil society representatives. These horizontal personal connections were forged in the years before the 2022 full-scale Russian invasion, fostered by instructive training sessions and seminars on strategic communications. Consecutive Ukrainian deputy ministers of defense have been leading figures in these recurring events, which covered diverse topics, exposing participants to collaborative work under pressure, networking, and joint problem-solving. This collaborative atmosphere involved a range of actors, such as military and intelligence personnel, civil servants, academics, journalists, and public figures. Consequently, a culture of continuous networking and informal communication flourished.

In essence, Ukraine’s investments in strategic communications reflect a concept based on international alignment with NATO mixed with strong internal Ukrainian networks that developed in the years leading up to the invasion. This approach has leveraged networking as a method for success.

Activities in the information environment, often facilitated by cyberspace, bring together previously separate activities such as mass communication and intelligence. In Ukraine, this has resulted in impactful outcomes—the observations of which should not be disregarded by anyone searching for lessons. Ukraine has grasped the importance of collaboration among government ministries, military actors, and civil society.

But this effort has developed entirely organically. External influences have played a role in shaping Ukraine’s strategies for operating in the information environment. Influences from the former Soviet Union and Russia have had a lasting impact. Clear parallels can also be drawn between Ukraine and Israel, wherein initial failures in the information environment led to enhanced interagency cooperation and the involvement of tech-savvy personnel who understand the dynamics of the online world. And notably, Ukraine has also eagerly embraced the strategic communications concept of NATO, albeit with a Ukrainian touch that emphasizes networking over rigid doctrine.

It would be wise to take note of Ukraine’s approach in the ongoing conflict with Russia. Despite being outmatched by Russia in 2014, Ukraine has transformed into a nation that steadfastly defends itself against the Russian onslaught, rallying Western and other allies for support and setting a strong model for a government’s use of the information environment in times of conflict.

No comments:

Post a Comment