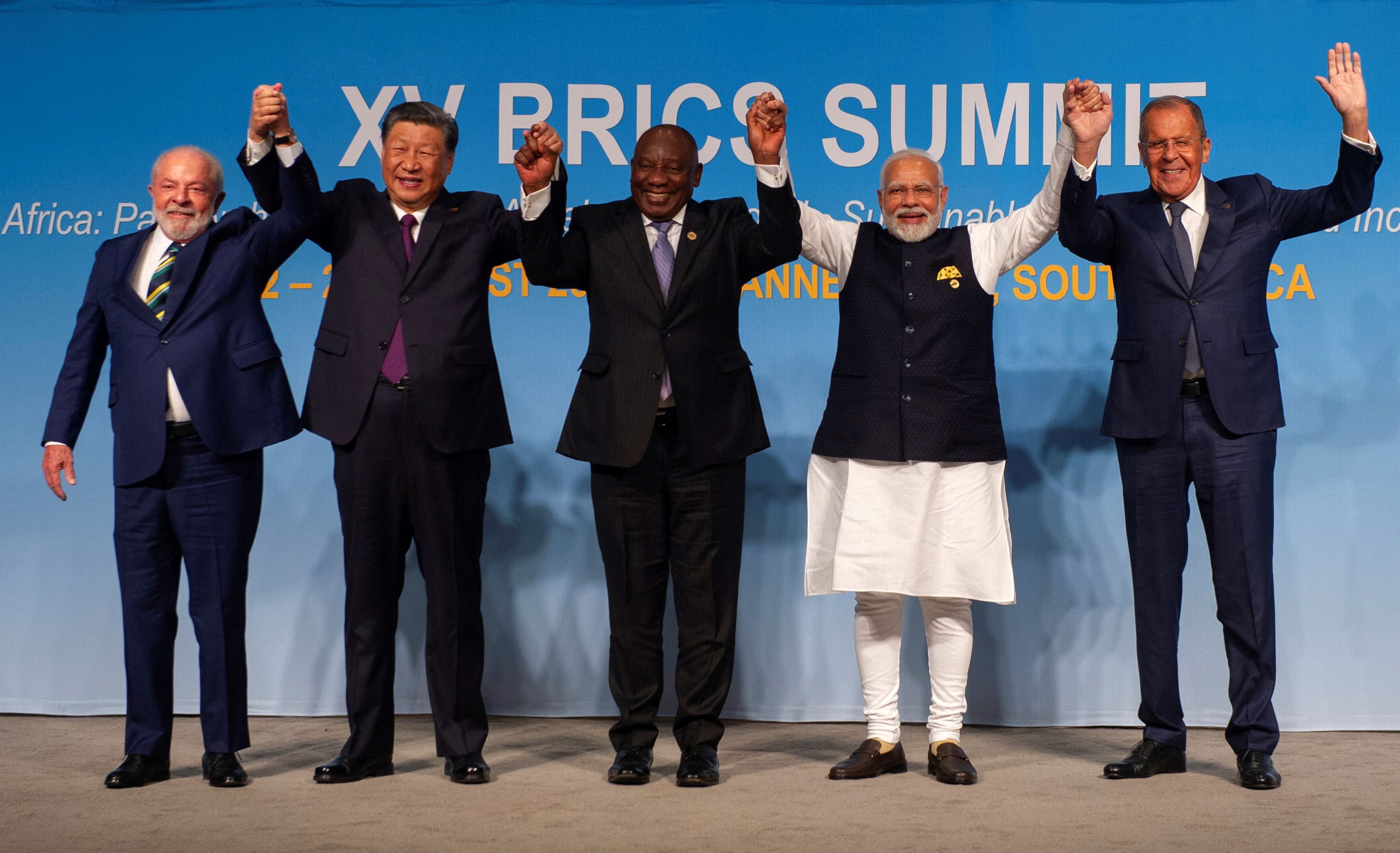

The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) bloc met for its annual leader’s summit in Johannesburg, South Africa on August 22–24, 2023. The highlight of the fifteenth summit was the agreement to admit six new member countries: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, who will officially join the group in January 2024. Ten Council of Councils (CoC) experts from BRICS members and beyond reflect on the future of the grouping and what expansion means for global governance.

The World Should Welcome the New Kids on the Bloc

The fifteenth BRICS summit has gone further than any other in the recent past to modernize and galvanize the grouping. It has sent a strong signal that the post–World War II order should accept the multipolar reality and change with the times.

The slew of applications to join the BRICS is clearly a symptom of a deeper malaise. The West’s proclivity to deploy unilateral financial sanctions, abuse international payments mechanisms, renege on climate finance commitments, and accord scant respect to food security and health imperatives of the Global South during the pandemic are only some of the elements responsible for the growing disenchantment with the prevailing international system.

The expansion of the BRICS to a BRICS+ format and the adoption of guiding principles, standards, and procedures for the same, have potentially made the BRICS a more attractive institution for consensus-building and dialogue in the developing world. Even the profile of the new members suggest that the system is headed for something beyond traditionally “acceptable” partners in the eyes of the West. The presence of Iran especially and the reactions to it in the coming days will be interesting to follow.

Another important aspect will be how these partners tap into the new systems of cooperation that the BRICS has been attempting to set up. Hype about a common BRICS currency might be impractical and premature, but trading in national currencies is becoming a reality. The recent rupee-designated oil transaction between India and the United Arab Emirates is not merely a swipe at the petrodollar arrangement that has prevailed since 1973. It is also a signal that the world’s major commodity exporters and importers can try to reduce their dependence on the dollar. If not a new world order, the BRICS expansion is certainly an attempt at an alternative world order, one with a more sympathetic ear for the developing many versus the developed few.

The challenge ahead will not be who joins the BRICS as a partner country but who holds the key to decisions on policy positions. The consensus-driven decision-making process of the BRICS will not make policymaking easier but the attempt to democratize is worth a serious effort.

The Geopolitical Moment of the BRICS+

The fifteenth BRICS summit will be remembered in two ways: as a summit that decided on the transformation from the BRICS to the BRICS+ and as a summit of complaints against the West for its responsibility for crises and wars and its inability to even control the consequences of these events. What some observers call a negative coalition of states that cannot agree on a common position, but can create a consensus on what they oppose, is growing in number to avoid sanctions and protectionist measures. The old scripts of belonging to a certain order are no longer valid because the reliability of traditional partners has changed. Meaningful narratives about old forms of order that have become fragile are losing their binding effect. New horizons of possibility are seized in anticipation of new options for action, pointing clearly to the urgent need to reorder international relations to overcome the self-referentiality of the West.

The refusal to be drawn into a contest of competing global powers is a general perception in the Global South that should not be underestimated. Western countries need to understand that the BRICS+ will continue as a loose grouping heterogeneous in its membership but with high aspirational dimensions seeking to expand its practical capabilities for other countries around the globe, especially a wider projection of the New Development Bank. The accusation that the West is arrogant toward the needs of the Global South is serious. It cannot be answered by offering “value-based partnerships” and a “rules-based” multilateralism when the interest of the BRICS is focused on changing those rules in global finance, trade, and other standard-setting procedures.

Although the BRICS+ has not elaborated on a model of global governance, and the democracy and human rights records of several of the new invited members are more than poor, the G7 needs to be aware that the formation of BRICS+ is more than a mere political maneuver to advance China’s vision of international order. All the BRICS+ members and the future group of partner countries have their own agendas and the BRICS forum is one of the various platforms on which member countries try to promote their vision of the word, especially for their participation with better conditions in the global economy.

The BRICS+ countries have seized their geopolitical moment and called for a united stand of emerging and developing countries against a world order and practice of international politics that does not correspond to their needs and necessities. Apart from Russia’s interest in presenting itself as a recognized member of the international community, the anti-Western narrative is not dominant among the BRICS+ states. However, signs are clear that the Global South is calling for a new form of open and inclusive multilateral cooperation overlooking the domestic situation of the partners—certainly a challenge for the West in times of uncertainty.

The Quest for Global Influence

A critical moment in the creation of a new world order may have just occurred. After horse trading and arm twisting, the BRICS is now the BRICS-plus-six. The new members will add their voices to advocating for a more equitable global governance system, reforming the UN Security Council, and increasing influence for the Global South.

The expansion signifies a growing alignment of geopolitical and economic agendas within the BRICS. It incorporates major global oil producers near crucial trade chokepoints, such as the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz and Bab-al Mandab Strait. India, Iran, and Russia are already developing the International North-South Transport Corridor. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, two of the world’s largest oil and gas exporters, supply most of China’s energy imports. Brazil, the last BRICS member to approve the expansion, specifically requested Argentina’s inclusion, which was reportedly a precondition for Brazil agreeing to the expansion as a whole. As the host, South Africa successfully negotiated the inclusion of two African countries, strengthening its ongoing efforts to promote integration, development, and growth through the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Russia’s 2024 BRICS presidency will focus primarily on using local currencies and payment systems, steered by discussions among finance ministries and central bank governors. However, a larger membership also means greater challenges to reaching consensus and adds new layers of complexity. Egypt and Ethiopia continue to dispute the management of the Nile River. Although a Chinese-brokered deal has eased tensions, Saudi Arabia and Iran remain historical rivals for regional dominance in the Middle East. Argentina, facing economic challenges and an impending contentious presidential election, has an uncertain political future. Iran's inclusion is set to make the bloc more assertive and vocal in its criticism of the West, targeting the United States and Israel in particular. Meanwhile, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, both modernized and oil-rich nations, increasingly focus on Asian commodity markets.

The BRICS expansion has now located countervailing forces and interests at the heart of the club, which could make it difficult for its democracies—Brazil, India, and South Africa—to straddle the global geopolitical divide.

The BRICS Is Not an Anti-Western Association Per Se

When the world is experiencing an acute geopolitical conflict, any event is viewed exclusively through its prism—the United States versus Russia and China, the West versus the Rest, democracy versus autocracy, and so on. Accordingly, the conflict will always see a winner and a loser. The BRICS summit in South Africa is no exception, especially given that the contestation appears embedded in its composition. Now experts talk both about the success of the non-West, which is expanding, as well as the West’s victory, because the BRICS+ remains an amorphous, non-institutionalized group.

In fact, the outcome of the Johannesburg summit should be considered not from the point of view of rivalry but in the context of objective international trends. The supporters of turning the BRICS into an anti-Western association could not prevail. Apart from Russia, the members are not interested in direct conflict with the West. Moreover, interests of member states coincide only to a certain extent. The decision to invite new members is a choice of development model for the next stage. At the fork in the road between deepening and institutionalizing ties or expanding outward, the BRICS chose expansion. The accession of countries will now be regular. Judging by the set of first invitees, no clear membership criteria is established, only the matter of agreement among those at the table. Only one condition applies—no binding relations with the West.

As a result, the direction has been determined. The BRICS will move toward the alter-West rather than the anti-West. The grouping will expand the space of interaction bypassing the Western world and without the participation of Western countries. Each of the BRICS states is free to develop its relations with the United States and Europe, but it should not harm its relations with the BRICS states. Current and future BRICS members have one thing in common: they reject the right of the United States and the European Union to impose restrictions on other countries’ foreign policy and economic activities. The BRICS space can be developed as a tool for diversifying the world and moving away from Western domination toward a far more multifaceted scenario. It will be further enhanced and strengthened in the process, albeit a long process.

A Greater Voice for Developing Countries

This year’s BRICS summit attracted unusual international attention, largely because of its relevance to the increasing importance of the Global South in today’s world affairs. More than twenty countries formally expressed their willingness to join the BRICS, which likely prompted the Group of Seven countries to strengthen their outreach to the Global South at this year’s Hiroshima summit. It appears that both the G7 and BRICS are competing for influence in the Global South.

The Global South’s economic growth potential and increasing security influence is contributing to its rising global importance. The United States and European Union have proposed their version of infrastructure and development initiatives, following China’s Belt and Road Initiative, that will ideally free more resources for the Global South countries to achieve their respective sustainable development goals.

However, the G7 engagement and the BRICS engagement toward the Global South differ significantly. The G7 only occasionally invites Global South countries for partial dialogues. The BRICS have now recruited six influential full members from the Middle East, North Africa, and South America. This expansion also shows the ability of the five established BRICS members to reach consensus. In addition, the BRICS foreign ministers are developing partner country models to further meet the engagement demands from other countries in the Global South.

The BRICS vision is to demand a greater voice for developing countries in world affairs, as South African President Cyril Ramaphosa referenced at the recent summit when recalling the Bandung Conference of 1955. Given that the next three G20 chairs are BRICS members, the Global South’s voice will be integrated into the G20 agenda. In addition, BRICS leaders showed appreciation for the African Leaders Peace Mission’s proposal for a peaceful resolution to the Ukraine crisis. Both demonstrate that the BRICS prioritizes the Global South’s agenda and demands for international influence and respect, something the G7 appears to be approaching differently. In this perspective, it may be a clue to the rising attractiveness of the BRICS for Global South countries.

Expansion Will Test the BRICS’ Cohesion and Effectiveness

The addition of six new members underlined the BRICS’ determination to create a bloc of major emerging economies to represent the interests of the developing world. It was clear in the lead up to the summit that the group’s aims resonated with many developing countries, with some forty countries applying or indicating interest in joining the group.

The group aspires to reshape global governance by increasing trades in local currencies, reforming the United Nations and International Monetary Fund to better accommodate the aspirations of emerging countries, and aligning positions on global issues such as on agriculture, health, and sustainable development. The summit’s statement highlighted that while the BRICS seek to supplement and reform existing international institutions that are deemed to be unresponsive to their interests, it does not seek to challenge or replace existing groupings such as the G20.

Moving forward, the group’s expanded membership could be a double-edged sword. The incorporation of U.S. allies such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia alongside countries ambivalent or opposed to the United States could frustrate efforts at deepening cooperation between member-states. Members would need to decide if BRICS is to be a bloc of emerging economies seeking to promote their interests in a multipolar world order or adopt a more explicitly anti-West orientation, the latter of which is preferred by China and Russia.

Indonesia was conspicuously absent from the list of new BRICS members. With the world’s fourth largest population and a major emerging economy in Southeast Asia, Indonesia was invited to join the BRICS on multiple occasions. Indonesian President Joko Widodo attended the Johannesburg summit and said that Indonesia largely shares the group’s priorities and interests. However, the president made it clear there is currently no urgency for Indonesia to join. It is likely that Indonesia will wait to see if BRICS member-states are able to resolve the group’s identity crisis, establish a more coherent vision, and become more institutionalized.

The challenges and opportunities presented by expansion will test the BRICS’ cohesion and effectiveness. Its ability to remain a credible force for reshaping global governance will depend on its capacity to forge consensus among its diverse members.

Brazil and the BRICS: Focus on Multipolarity and Multilateralism

The defense of multilateralism is a core characteristic of Brazilian foreign policy, except on rare occasions, such as in the Bolsonaro government. In this context, the BRICS has always been understood as a constructive platform to contribute to the reform of multilateral institutions. The growing economic weight of the BRICS members merits demands for a larger role in economic governance reforms. The BRICS countries want more power in multilateral decisions that guarantee a greater degree of domestic autonomy or flexibility (or both) in their respective development agendas.

The entry of six new members has led to a debate on the future trajectory of the BRICS and Brazil’s role in it. The Lula administration was originally against expansion because it would reduce Brazil’s bargaining power within the bloc. However, as a defender of greater participation from the Global South, Brazil accepted expansion, and the addition of Argentina was a positive sign.

It is difficult for Brazil, as a defender of strengthening democracy and human rights, to justify belonging to a group that includes Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Human rights was not on the BRICS agenda, and Russia and China are not democracies, so this is not an issue for the Lula administration. Besides, nondemocratic countries belong to various multilateral institutions.

The most controversial issue for Brazil, however, is the defense of nonalignment and neutrality in tensions between the United States and China and in the war in Ukraine. The inclusion of countries with clear anti-Western bias signals support for and reinforces similar positions of Russia and, occasionally, China.

Brazil, India, and South Africa, the oldest members, will have a difficult time ensuring that the new BRICS is not a platform for defending the geopolitical interests of China or Russia. Topics that are of interest to the Global South as a whole should be prioritized: cooperative mechanisms for energy transition, technology transfer, financing the New Development Bank, resumption of the World Trade Organization dispute settlement mechanism, and UN Security Council reform. The signing of the Mercosur-European Union agreement and accession to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development would also reinforce Brazil’s role as a non-anti-Western BRICS member. This is the role Brazil should play in BRICS, a platform that contributes to multipolarity and multilateralism.

Summit Displayed South Africa’s Contradictory Foreign Policy

For several weeks in the run-up to the BRICS summit, the entire event threatened to be a massive headache for the host country. The South African government’s enthusiasm for BRICS expansion faced both widespread skepticism about whether the bloc could agree on criteria for admission and tension around the country’s contradictory obligations as summit host and Rome Statute signatory, which in turn led to much hand-wringing about how to handle a potential visit from Russian President Vladimir Putin given the International Criminal Court’s warrant for his arrest. In the end, these problems were resolved. South Africa can rightly boast that the gathering exceeded expectations.

However, even though South Africa’s government clearly sees the summit as a win for the country and its stature, the summit was also a venue that underscored the contradictions in the country’s approach to foreign policy. In President Cyril Ramaphosa’s speech to the nation just days before the summit, he underscored the value of South Africa’s diverse foreign partnerships and sought to bring clarity to his government’s policy of nonalignment. In his remarks, he reminded the country of how the advent of democracy in 1994 radically changed South Africa’s relationship with the rest of the world, and went on to list “the promotion of human rights” as first among the “key pillars of our foreign policy.” The distance between a foreign policy grounded in a democratic identity and committed to promoting human rights and an embrace of a global order shaped by China and Russia—and now Iran, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia as well—is considerable. The gulf between the story South Africans like to tell themselves and the reality of their government’s nonchalance toward repression and aggression as long as it is within states that position themselves in opposition to Western powers is hard to ignore.

Still, South Africa may have captured the regional zeitgeist by seizing on legitimate frustration with the status quo to embrace a fairly inchoate idea about a new global order (one cannot help but reel at the prospect of Ethiopia joining Saudi Arabia, a country that has reportedly been mowing down Ethiopian refugees, in a group aimed at addressing global inequities). Certainly other African governments share a desire for a multipolar order and meaningful reform to the international institutional architecture that was largely designed without their input. Just what those reforms will look like, and whether they actually serve African interests, remains to be seen, however.

No comments:

Post a Comment