Dheeraj P.C.

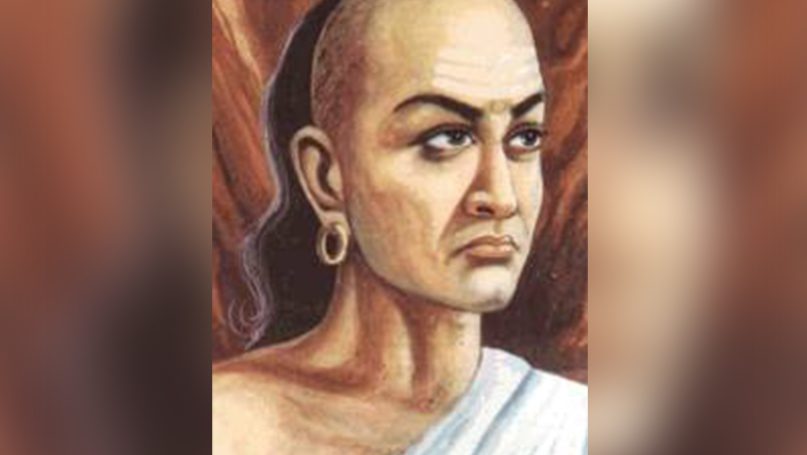

Why are nations surprised? National security surprises take the form of traditional military attacks such as the Pearl Harbor attacks (1941), the Yom Kippur War (1973), or the Kargil War (1999), or non-traditional surprises such as the devastating terrorist attacks of 9/11, 7/7, and 26/11, to name a few. How do nations guard against such surprises? Generic perception around the world points to better intelligence and forewarning. Indeed, intelligence bureaucracies around the world found their births owing to some form of military surprise. However, academic studies on strategic surprises remain divided between the inevitability of surprise versus its preventability owing to timely and precise intelligence. Where modern scholars have largely built their arguments on the postmortems of alleged intelligence failures and instances of strategic surprises, ancient Indian treatises on statecraft engaged this question at a theoretical level. Against this backdrop, this article presents a brief on Kautilya’s approach to strategic intelligence for foreign policymaking as espoused in the text—Arthashastra. Kautilya’s intellectual engagement with strategic intelligence is elaborate and cannot be captured entirely in this article. Therefore, what follows is a limited exposition on Kautilya’s ideas on intelligence analysis to avoid strategic surprises, extracted from a chapter of my book.

A simplistic answer that Kautilya would give to the problem posed above is to consider the inevitability of surprises and hence maximise power to achieve deterrence. Accordingly, a combination of the tangible (prabhava shakti) and the intangible (utsaha shakti) aspects of hard power is the best insurance against any enemy actions. However, in adequately utilising hard power, Kautilya emphasises another aspect of power called mantra shakti that is derived from knowledge and intellectual competence. It is in this realm that Kautilya believes that a state can and should do everything in its ability to both avoid being surprised as well as adroitly employ power towards maximisation of national interests. According to him, if the cause of the surprise is knowable, and hence, foreseeable, then it is a clear instance of intelligence failure. Such failures arise out of errors – human or structural – that ought to be rectified.

The origin of this prognosis is linked to how Kautilya views the construction of a state’s foreign policy and the elements that determine it. Accordingly, any state derives its foreign policy choices from sadgunya (the six choices), which is in turn determined by the saptanga (the strength of the seven key elements). Thereby, the foreign policy choices available to a state are:

- Samdhi (peace) – determined by the superior power of the rival state.

- Vigraha (war) – determined by the power inferiority of the rival state.

- Asana (neutrality) – determined by the balance of power between the two states.

- Yana (war preparation/coercive diplomacy) – determined by the relative increase in power against the rival state.

- Samsraya (alliance formation) – determined by the faster growth of the rival power.

- Dvaidibhava (diplomatic double game) – fluid constellation of rivals and allies.

The likelihood or unlikelihood of being surprised, according to Kautilya, depends on the accuracy with which one can determine the enemy’s choice within the sadgunya framework. To do so, Kautilya directs his analysts to focus on the seven constituent elements of the state (Prakriti); for the policy choices depend entirely on the cumulative strengths of these elements. The seven elements are the king, the councillors and ministers, the territory and its people, fortified towns and cities, the treasury, the military, and its allies. The combined strength of the seven elements both in quantitative and qualitative terms will determine the foreign policy choices of the state. Hence, the accurate estimation of these, aimed at forecasting the probable foreign policy choice of the rival state, is the goal of the strategic intelligence endeavour of the Kautilyan state.

Modern day strategic intelligence estimates have had mixed results in successfully influencing policies. Recent scholarship has begun to realise the limitations of strategic intelligence on policymakers. Kautilya, on the other hand, was aware of such complexities. Hence, where modern democracies divide intelligence and policy between dedicated intelligence bureaucracies and policymakers respectively, Kautilya made the policymaker, the leader of the strategic intelligence process. In so doing, he states that “whatever character the king has, the other elements also come to have the same, for they are all dependent on him for their progress or downfall”. For today’s scholars of intelligence, this can be sacrilegious since the intelligence product must be independent of political interference and uphold the spirit of ‘speaking truth to power’. Yet, there are scholars who believe that intelligence is not about ‘telling truth to power’ since it is incapable of knowing the whole truth and is only meant to reduce uncertainty, which gives the policymakers the freedom to accept or reject it.

Bearing in mind such complexities, Kautilya divides strategic intelligence into three different types of knowledge:

- Immediate knowledge based on what the ruler himself sees and hears – with their own international networks, policymakers have their independent sources of information. Former Indian intelligence officer, B Raman, has recorded how “some of the Indian Prime Ministers were well-informed about important developments in the region and the world”.

- Mediated knowledge based on what the ruler hears from his ministers, spies, diplomats, and other experts – such information is a product of both intelligence collection and analysis.

- Combined knowledge with respect to future developments and own intended actions – self-explanatorily, this indicates that the ultimate form of knowledge emerges when intelligence estimates meet other factors guiding policy choices.

Thus, by making the policymaker the leader of the strategic intelligence programme, Kautilya gave the intelligence bureaucracies a realistic picture of their influence on policy. For greater efficiency, however, he mandated subject matter knowledge (sastras) for the policymaker.

With such an appreciation forming the basis for intelligence in the Kautilyan state, the bureaucracies were shaped to focus extensively on collection at the grassroots level of the organisation, whereas analytical responsibilities got formed hierarchically (see table 1).

Station chiefs oversaw operations, both collection and covert action. Analytical rigour at this level was limited to testing the veracity of information and reliability of the sources. It is prescribed that no information can be considered authentic unless verified by three independent sources. This shows Kautilya’s awareness of deception and misinformation as being the enemies of intelligence. A few years after India’s independence, the then Home Minister, C. Rajagopalachari had given a similar advice to the Director of Intelligence Bureau, B.N. Mullik, which the latter claimed to have incorporated as operational practice. However, the source of Rajagopalachari’s advice was not the Arthashastra but the Kural—a classic Tamil text, indicating the exchange of knowledge on statecraft across the lengths of the country.

Above the level of the station chiefs, the minister of intelligence performed all-source analysis and offered advice to the king. In conducting the all-source analysis, Kautilya recommends using all the intellectual might the state can marshal (yathásámarthyam) to tackle the issue at hand. However, where policy recommendations are in question, Kautilya recommends limiting the body to four members. The logic here is that four analysts are adequate to tackle the challenges of both group think and conflicting analyses. The ‘combined knowledge’ thus produced, and in possession of the ruler, becomes the basis for policy. The entire process thus far narrated serves one key objective, i.e., aversion of surprises. In the event of a lapse, the defence capability of the state must be prepared to tackle the challenges born therewith. And therein lies Kautilya’s emphasis on power maximisation.

Therefore, in the Kautilyan state, intelligence analysis formed the bedrock of foreign policy formulation. Yet, it was structured in a manner to reflect its limitations on policymaking as well as complemented by the existence of an expanding state power to tackle surprises.

No comments:

Post a Comment