THERESA HITCHENS

WASHINGTON — While it likely will be impossible to completely deter adversary attacks on US space systems, a strategy that takes a mixed approach — including diplomacy at one end and offensive counterspace weapons at the other — is most likely to be successful, a new RAND Corporation study finds.

“A comprehensive approach to space deterrence—one that seeks to regulate the use of force in space in the interest of stability; ostracizes states that violate agreed-on norms; and allows states to retain some capacity to punish space aggressors in multiple domains and to develop measures to enhance the defenses, resilience, and redundance of space systems—may have the greatest probability of success,” the study, “A Framework of Deterrence in Space Operations” released today, finds.

Stephen Flanagan, the lead author on the study, explained in an email to Breaking Defense that the concept is one of “mixed deterrence,” that works through “a mix of resilience and defensive measures, combined with robust active defenses of space assets and more substantial capabilities to degrade the space systems of other countries.”

This approach includes US Space Command and the Space Force not just highlighting “continued investments in space mission assurance and resilience,” but also cooperation with allies and partners, he added.

Noting that “there is no broadly agreed-on framework in the U.S. or allied governments or the wider analytic community on the nature and requirements of deterrence in space operations,” the study explains that the study’s goal is present suggested guidelines to policy-makers both to understand how other nations think about space deterrence and make decisions.

The study further notes that there is no agreement upon international definition of what constitutes space deterrence or how to achieve international stability among potential adversaries either in peacetime or crisis.

“Various countries have quite different conceptions of what the term means and how it can best be achieved,” the study says. For example, Chinese and Russian writings reveal an aggressive approach based on “intimidation” and threats; whereas those of France and Japan show a more “passive” one. India, where strategic thinking seems to still be in play, falls somewhere in between, it adds.

At the same time, the RAND authors stress that a foolproof space deterrence strategy is almost certainly out of reach.

“The prospects for complete success in deterrence of hostile attacks on space assets, particularly reversible, nondestructive attacks, are limited. Reversible attacks are the most difficult to deter because adversaries assess that they have lower risks of a robust response or escalation,” the study explains.

Thus, efforts would be better focused on “mitigating damage and preserving essential capabilities through a mix of defensive and offensive counterspace actions, resilience measures, and reconstitution,” it adds.

That said, RAND suggests decision-makers also should avoid going too far toward an “offense dominant” approach that focuses on “punishment” of adversaries and emphasizes counterspace weaponry to avoid undercutting space “stability.” Indeed, the study finds that because of the nature of the space environment, even some actions intended to defend national capabilities could easily be seen as adversaries as “plans to attack.”

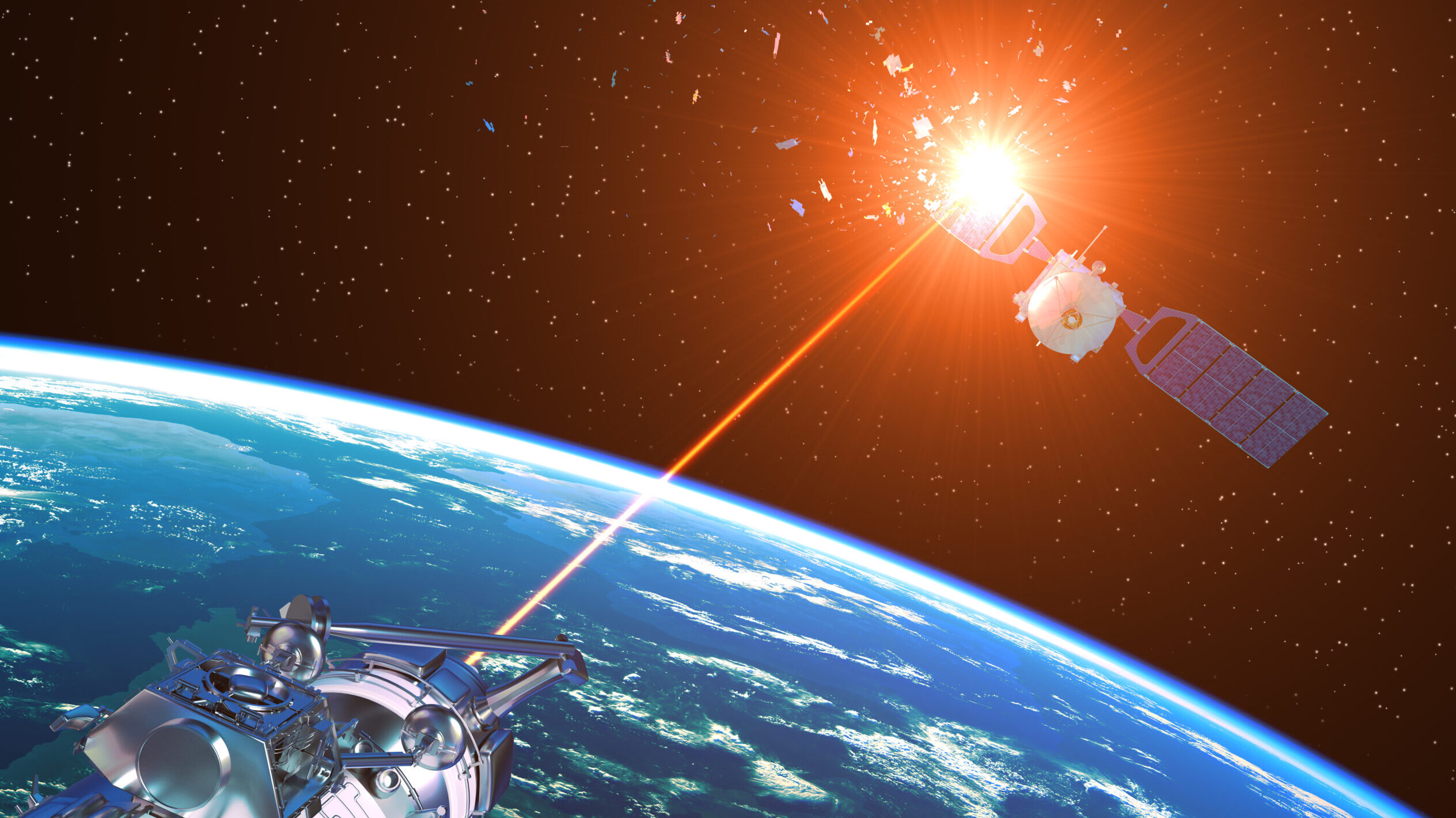

“For examples, space deterrence will plausibly be relatively more unstable if states deploy large arsenals of ASAT [anti-satellite] systems; such systems may make war in space appear inevitable. If these missiles are postured in ways that makes them vulnerable to a preemptive attack, such a scenario could be even more unstable. Deployment of orbital ASAT weapons could also create ‘use or lose’ incentives in a crisis to prevent an adversary from launching a first strike that would destroy or disable critical satellite systems,” the study says.

Instead, RAND finds that better results are likely by including in any strategy efforts to provide “assurances” to potential adversaries that restraints on aggressive and/or threatening actions will be rewarded in kind. In addition, it notes, such measures also could be useful in identifying “off-ramps” in crises, avoiding escalation into warfare.

Further, the study says that diplomatic measures, including norms that constrain some military space activities, also help to bolster space deterrence. (An example of such a norm is the Biden administration’s push to voluntarily obtain global commitments to forgo testing of destructive, direct ascent ASAT missiles.)

“Although imperfect and not enforceable, non–legally binding norms of space behavior could help build confidence among space-faring nations and enhance stability and deterrence by creating rules of the road and thresholds that would be clear warnings of hostile intent,” the study says.

“Strategic messaging, deliberate revelation of selected space capabilities, and the development of international norms of responsible space behavior can enhance stability and deterrence in the space domain,” the study asserts.

The suggestion that certain capabilities should be revealed echoes the years-long debate within the US national security community about whether the Pentagon should declassify more information about its own counterspace capabilities in order to help deter Russia and China.

“Effective deterrence does require that hostile powers are aware of the general scope U.S. counterspace capabilities,” Flanagan explained. “However, given the dependency of the U.S. military and Intelligence Community on space, particularly before the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture is in place, statements or actions that suggests the United States has an aggressive counterspace strategy and capabilities may only encourage Chinese and Russian preemption in a crisis.”

Thus, he added, US officials should keep in mind Teddy Roosevelt’s famous dictum: “Speak softly and carry a big stick.”

No comments:

Post a Comment