Captain John T. Hanley

Former Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Michael Gilday’s Navigation Plan 2022 calls for a “rigorous campaign of learning” as part of a “continuous, iterative force design process to focus our modernization efforts and accelerate capabilities we need to maintain our edge.” He identifies a “learning culture” as essential.

Former Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Michael Gilday’s Navigation Plan 2022 calls for a “rigorous campaign of learning” as part of a “continuous, iterative force design process to focus our modernization efforts and accelerate capabilities we need to maintain our edge.” He identifies a “learning culture” as essential.The Navy during World War II developed a learning culture modeled on the Prussian campaign of learning. The Navy’s campaign dissipated following the war, as the national security establishment and the Navy evolved, though the submarine force and the CNO Strategic Studies Group successfully used similar campaigns during the Cold War. An attempt to re-create a campaign of learning for naval warfare innovation failed in the 1990s. The learning initiatives in Navigation Plan 2022 are essential for regaining headway in competition with China.

U.S. Navy Reforms

The Prussian campaign of learning balanced theoretical study and practical experience and exercises, including war games. Leading U.S. Navy reform, Stephen B. Luce sought to follow the Prussian campaign, resulting in the founding of the Naval War College (NWC) in 1884. Luce explained his idea for the college declaring, that “there are no professors competent to teach” warfare. “All here, faculty and class alike, occupy the same plane, without distinction of age, rank, or assumption of superior attainments.”1

The first NWC curriculum included Alfred Thayer Mahan’s theoretical lectures—which lead to books such as The Influence of Seapower upon History and The Problem of Asia—assisted by war games developed by McCarty Little for learning naval concepts. In 1894, games became an integral part of the instruction, with a selected adversary studied each year.

Rear Admiral William S. Sims, president of the NWC following World War I, emphasized the practical over the theoretical and preparing minds versus preparing plans. Using games to test new principles and plans for future operations was secondary to building character and developing leadership skills—grooming officers for command at sea.

In the 19th century, the Secretary of the Navy directed Navy operations. When the Spanish-American War came along, Secretary John Davis Long received competing war plans from the NWC, naval intelligence, and the Bureau of Navigation. As a result, Long created a General Board in 1900, led by Admiral George Dewey and other distinguished admirals, to oversee war plans and manage the disparate Navy bureaus and offices, with the president of the NWC, a senior Navy intelligence officer, and the head of the Bureau of Navigation as ex officio members.

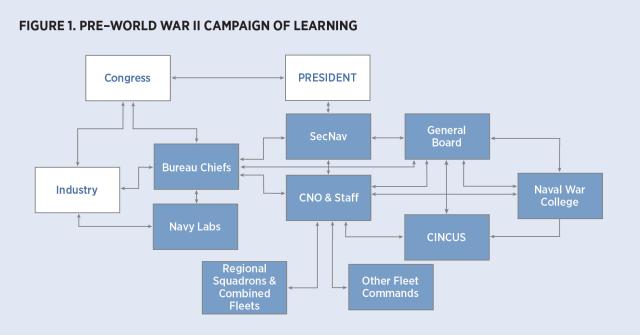

Overcoming congressional fears about creating a Prussian-style general staff and the opposition of Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, Admiral Bradley Fiske championed legislation in 1915 that created the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). The Office of the CNO (OpNav) took over war planning from the NWC and General Board, but a web of interactions among the CNO, the General Board, naval intelligence, the NWC, fleet commanders, and technology developers led to an interwar campaign of learning. Under the CNO, this Navy-wide effort orchestrated annual Fleet Problems to develop operational and tactical concepts using emerging technology (Figure 1).2

This learning culture prepared the Navy for victory in World War II. Leaders such as Ernest King, Chester Nimitz, Raymond Spruance, Richmond Kelly Turner, Charles Lockwood, and others learned from every operation.3 They developed the combat information center to allow rapid decision-making and fleet tactics in which short codes instructed task forces to adopt a particular formation.4

Punctuated Evolution

Although war games continued at the Naval War College after World War II, the curriculum shifted from naval strategy and tactics to strategy and policy, with students more often playing the role of national decision makers and less focused on the roles of tactical and operational commanders. Naval History and Heritage Command

Following the war, the national security establishment experienced a punctuated evolution. Contributions from top mathematicians such as Alan Turing and John von Neumann and other scientists led to computers and atomic weapons. The successes of scientists such as Philip Morse and Bernard Koopman supporting the Tenth Fleet created a new discipline of operations research.5

The National Security Act of 1947 created a powerful Secretary of Defense. President Harry S. Truman—fearing a recession as the war wound down—focused on stabilizing the U.S. economy, devoting as little funding as he could to defense.6 Louis Johnson, who followed James Forrestal as Secretary of Defense, believed all the country needed was an Air Force and atomic bombs. He demobilized Army and naval equipment as quickly as he could until the Korean War reversed the process.7

Johnson’s cutting the Navy’s plan for a supercarrier and his attempts to muzzle dissent led to a revolt of the admirals and CNO Admiral Louis Denfeld being fired. Rivalry between the Navy and Air Force was fierce. Conditions were set for competition for scarce budgets, both among the services and the warfare branches within them.8 By the time Arleigh Burke became CNO in 1955, the Pentagon’s focus was finely tuned to budgets and programs.9

In President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s farewell speech, he addressed perils of both the military-industrial complex and the rising influence of defense intellectuals.10 Focusing the techniques developed during World War II for researching operations based on analyzing the cost-benefit of systems, McNamara established the planning, program, and budgeting system (PPBS) that continues today with few modifications.

In 1944, Navy Secretary Frank Knox appointed Vice Admiral William Pye, who had become president of the NWC in 1942, president of a board to study the methods of educating naval officers. Pye had participated on a similar board with Captain Ernest King (then head of the Naval Postgraduate School) and Commander Dudley W. Knox of the NWC in 1920. The board recommended that the NWC include three tiers: a command-and-staff course prior to command of a large ship, a course before commanding a division of ships, and an advanced course for flag officers.11

The NWC was never to achieve a scheme of education progressing with officers’ increased responsibilities over their careers, nor the stature in the Navy that it held before the war. Pushed for by Admiral Ernest King, in 1945, Congress passed legislation making the Naval Postgraduate School a fully accredited graduate degree–granting institution.

CNO Admiral Chester Nimitz made Spruance president of the NWC in 1946. The curriculum shifted from naval strategy and tactics to strategy and policy; games had the students playing the roles of national decision-makers rather than commanders. The curriculum lost its balance between practical reason and theoretical understanding. The web of interactions that had formed the campaign of learning disintegrated. The Pentagon focused on programs and budgets rather than strategies for defeating potential adversaries, and the fleet was organized for continuous deployment.

Because the NWC emphasized policy and strategy, the Navy sent few students who had the potential to become future Navy leaders.

PostWar Navy Campaigns of Learning

Though big Navy lost its culture of learning, several organizations created learning cultures similar to those of the interwar years. Facing demobilization, the submarine force established Submarine Development Group Two to develop antisubmarine warfare (ASW) tactics and technology. It used an open door to laboratories established during World War II and a program of designing frequent exercises using prototype concepts and technology, collecting data during exercises and forward operations, reconstructing engagements, and conducting unvarnished analysis. As a result, the submarine force went from having no ASW capability during the war to being the dominant ASW force within a decade.12

Other programs adopted the submarine force’s methods. Among the successes was finding that the Navy did not have the communications required to employ submarines as an outer screen for a carrier battle group, nor the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance to employ antiship Tomahawk missiles in a cluttered sea environment—resulting in a sole focus on land-attack Tomahawks. Using consistent data collection methods across multiple exercises and carefully reconstructing that data allowed the Navy to make informed tactics, organizational, and procurement decisions.13

In the 1990s, the CNO Strategic Studies Group (SSG) also employed a web of interactions in a campaign of learning that involved study, critical analysis, and war games that led to concepts for the 1986 Maritime Strategy. Many successful innovations came from a practical focus on both combat and other influence operations.

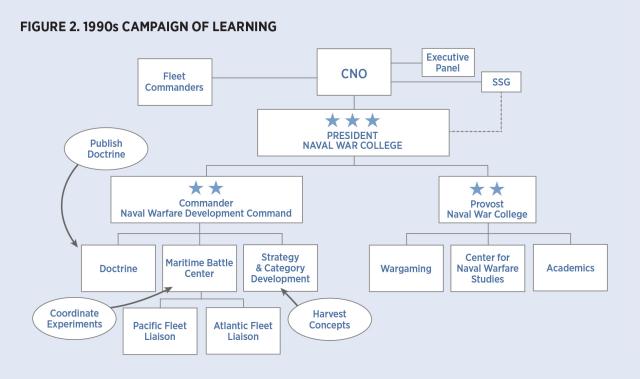

An effort to create a campaign of learning for naval warfare innovation in the 1990s failed. The CNO Executive Panel formulated a process, and CNO Admiral Mike Boorda directed the SSG to focus on concept generation. Unfortunately, Admiral Boorda’s death came as the first SSG he tasked readied to brief him on their concepts. Attempting to make this approach work, CNO Admiral Jay Johnson changed the mission and organization of the SSG to focus solely on naval warfare innovation and the NWC to “provide unity of effort by realigning Navy warfare doctrine development, concept innovation, and fleet experimentation with strategy development and wargaming under the command of the President, Naval War College.”14 (See Figure 2.)

The Naval Doctrine Command became the Naval Warfare Development Command and moved to Newport. However, no changes were made to the NWC curriculum or the relationship between the college’s theoretical academic and practical research sides. While the new organizational structure was consistent with a campaign of learning, absent the coordinating oversight of an organization like the General Board, the necessary interactions did not mature. The next CNO, Admiral Vernon Clark, moved Navy Warfare Development Command back to Norfolk to be closer to the fleet, and the NWC president reverted to a two-star admiral. OpNav provided no funding for demonstration. The Navy is now pursuing many of the SSG’s concepts from the 1990s.15

Implications

Each of the Navy’s communities depends on the others—OpNav should not be the focal point for the Navy’s campaign of learning. A modern General Board with the presidents of the Naval War College and Naval Postgraduate School, the Director of Naval Intelligence, heads of systems commands, the Chief of Naval Research, and regional fleet commanders convening to inform the CNO on which problems “big Navy” should focus would accelerate the learning campaign. The Education for Seapower Strategy 2020 should be implemented.16

When the SSG’s mission was making captains of ships into captains of war, of 88 officers assigned, the program produced eight four-star and ten three-star admirals. Absent a course for all flag officers, the SSG should be resurrected with this mission, using a similar program to the one that proved successful during the late Cold War.

The Secretary of the Navy and CNO should implement the recommendations of the two Pye boards, balancing practical and theoretical studies. The Navy should have a curriculum for officers headed to their first commands modeled after Sims’ use of theater-level games to develop character and command skills, learning how to fight outside their warfare specialties.

Officers headed to major command should have a similar curriculum balancing practical studies of specific adversaries combined with higher-level operational considerations, directly addressing Navy component commander roles in combatant commander plans. These courses would meet JPME Phase 1 criteria and satisfy demands for a master’s degree. In addition, the president of the Naval War College should be a post-numbered-fleet command three-star with oversight of the Naval Warfare Development Center to connect the fleet.

No comments:

Post a Comment