Brad Lendon and Simone McCarthy

China has built the world’s largest naval fleet, more than 340 warships, and until recently it has been regarded as a green-water navy, operating mostly near the country’s shores.

But China’s shipbuilding reveals blue-water ambitions. In recent years it has launched large guided-missile destroyers, amphibious assault ships and aircraft carriers with the ability to operate in the open ocean and project power thousands of miles from Beijing.

To sustain a global reach, the People’s Liberation Army Navy will need places for those blue-water ships to refuel and replenish provisions far from home.

New analysis from Washington-based think tank the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) says Beijing’s growing push for that port access includes helping to build a naval base in Cambodia and scouting other potential locations for military outposts as far afield as Africa’s Atlantic coast.

This is augmented by People’s Liberation Army (PLA) facilities in places like Argentina, FDD reports, and Cuba, that can do everything from monitor space and track satellites to eavesdrop on the communications of Western countries.

Together, experts say, these efforts aim to enhance China’s military reach, which currently includes only one operational overseas naval base in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa.

China maintains that the Djibouti base supports its anti-piracy and humanitarian missions in Africa and West Asia.

Chinese officials have repeatedly stressed that Beijing does not seek “expansion or spheres of influence” abroad and have pushed back on various assertions that it is cooperating with other nations with an eye to establishing overseas bases on their land.

But the FDD has gathered open-source intelligence and reporting to support its conclusion that China is building toward more naval outposts, including satellite imagery that shows the remarkable development of the Ream Naval Base, sitting on a stubby peninsula jutting from the west coast of Cambodia into the Gulf of Thailand.

“The PLA’s expanding global footprint and corresponding ability to conduct a wider range of missions, including limited warfighting, carries major risks for the United States and its allies in the Indo-Pacific as well as other operational theaters,” the report says.

And the PLA is not slowing down, said the report’s author, FDD senior fellow Craig Singleton.

“It’s a question of when – not if – China will secure its next overseas military outpost,” he said.

CNN has approached China’s Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Foreign Affairs for comment.

A tale of two piers

Chinese and Cambodian officials presided together over a ground-breaking ceremony for a Chinese-funded upgrade to the Ream Naval Base facility last year, with Beijing’s envoy in the country hailing military cooperation as part of the countries’ “iron-clad partnership.”

Cambodian Defense Minister Tea Banh at the time dismissed claims that it would become a Chinese military outpost, stressing during the ceremony that the project is in line with Cambodia’s constitution, which bars foreign military bases on its territory.

Chinese officials have described the base as an “aid project” to strengthen Cambodia’s navy and called assertions otherwise “hype” with “ulterior motives.”

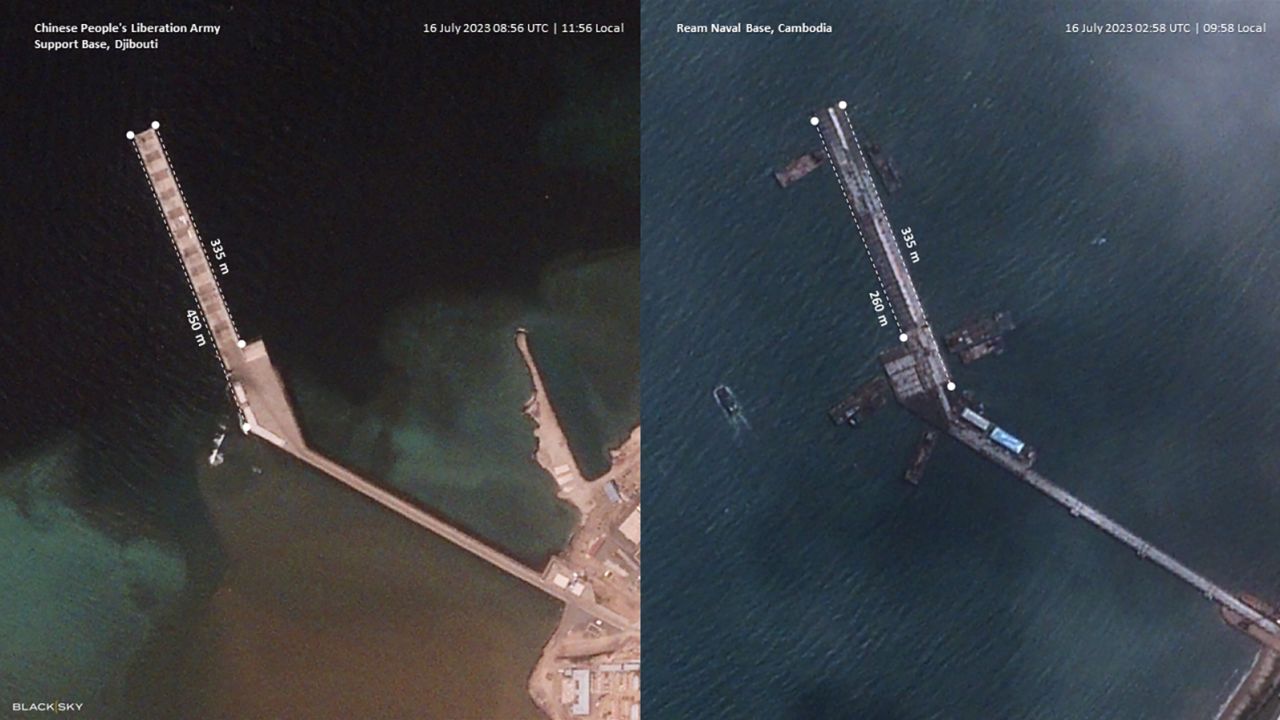

The FDD’s Singleton says its analysis of satellite imagery shows a pier being built at the Ream base has similar dimensions to one at China’s overseas military base in Djibouti.

The Djibouti pier has the ability to receive Chinese blue-water ships, and these similarities suggest that Ream could support such vessels too.

The Ream base is also more expansive overall, and Singleton and others wonder if it could be a blueprint of what’s to come for China’s military ambitions overseas – despite official denials of this aim.

“In 2016, Chinese and Djiboutian officials similarly denied reports that China intended to establish a military foothold in the Horn of Africa,” said the FDD’s Singleton.

“But, less than a year later, the PLA deployed ships from its South Sea Fleet to officially open its base in Djibouti, after which the PLA conducted six weeks of live-fire exercises,” he said.

That is not the only example of China saying one thing and doing another when it comes to its military operations.

In 2015, Chinese leader Xi Jinping pledged that Beijing would not militarize artificial islands that it was building in the disputed South China Sea.

But today Beijing uses military installations across those islands to bolster its territorial claims in the region.

A sea change?

China has long decried the US’ network of an estimated 750 overseas military installations, accusing Washington of undermining global security and using these outposts to interfere in other countries’ affairs.

But Beijing has become more assertive in its home region, using the military to press its claims in the South China Sea and intimidate Taiwan – a self-governing democracy that China’s ruling Communist Party has vowed to take, by force if necessary.

As its rivalry sharpens with the US, experts say Beijing has grown increasingly focused on finding ways to break what it sees as its physical “encirclement” by the US and its allies, while projecting its military might – and its vision for global security – abroad.

A 2019 defense white paper stressed the need for the PLA to protect its “overseas interests,” including through “developing overseas logistical facilities” – similar to the language it used to describe the Djibouti base.

China’s growing global clout and rapid expansion of its maritime commercial operations over the past decade has led to a more muscular approach to security on the seas, experts say.

Xi’s sweeping Belt and Road infrastructure financing initiative has been a springboard for Chinese firms to gain a stake in what experts say are dozens of ports around the world, which can also support some logistics and refueling for China’s navy and could host future military bases.

A recent study by AidData, a research lab at William & Mary University in Virginia, looked at where Beijing may put new naval bases from a financial standpoint, focusing on ports and infrastructure projects that have already gotten big money from China between 2000 and 2021.

“While our data is neither exhaustive nor definitive, we suggest a list of port locations — where China has invested significant resources and maintains relationships with local elites — that may be favorable for future naval bases,” AidData says.

Top of the list is Hambantota, Sri Lanka, followed by Bata, Equatorial Guinea; Gwadar, Pakistan; Kribi, Cameroon; Ream in Cambodia; Vanuatu in the South Pacific; Nacala, Mozambique; and Nouakchott, Mauritania.

The Hambantota commercial port in Sri Lanka has long been considered a prime candidate for a Chinese naval base.

Beijing gained control of the port in 2017, when a Chinese state-run company signed a 99-year lease with Colombo to run the facility – after Sri Lanka was unable to pay back the Chinese loans that built it.

“Naval cooperation was further cemented in 2018, when China gave a Type 053 frigate to the Sri Lankan Navy as a gift, rather than a foreign military sale,” AidData said.

Equatorial Guinea appearing second on the list shouldn’t be surprising. US military leaders warned on more than one occasion last year that Beijing was making moves there.

Army Gen. Stephen J. Townsend, commander of US Africa Command, told a US House hearing in March 2022 that China was actively seeking a military naval base on Africa’s western coast that could threaten US national security.

“The thing I think I’m most worried about is this military base on the Atlantic coast, and where they have the most traction for that today is in Equatorial Guinea,” Townsend said.

But US engagement with Equatorial Guinea, which is ruled by one of the world’s longest serving autocrats, may have put Bata on the backburner for Beijing, according to the FDD’s Singleton, who says there are signs China may be focusing on nearby Gabon instead.

“Gabon this year elevated its bilateral relationship with China from a ‘comprehensive cooperative partnership’ to a ‘comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership,’ one in which the two governments will almost certainly deepen collaboration in security and military-related domains,” Singleton said.

After Gabonese President Ali Bongo Ondimba, whose family had ruled the country for 56 years, visited Beijing in April to seal the upgrade in relations, he told China’s state-run Xinhua news service that “the two countries have reached a high level of consensus on preserving global peace and security, as well as resolving conflicts.”

A coup in Gabon this week, in which military officer placed the president under house arrest, brings new uncertainty to the China-Gabon relationship.

But no matter the exact details of any plan by Beijing to push forward military access in West Africa, Singleton said one thing is clear: “China aims to one day develop the capability to project its forces throughout the Western Hemisphere.”

Smooth sailing?

However, China’s path to developing permanent overseas bases, if indeed that is its aim, is not straightforward.

Many countries hosting US bases share defense treaties with the superpower, but China has a long-standing policy of not having formal allies – raising questions about the incentive for countries to welcome Beijing’s bases on their land.

Though China wields sizable economic clout that may help in that regard, governments that agree to host a Chinese military base could place their relations with the United States and its many allies in jeopardy amid growing rivalry and tension between the two powers.

And operating overseas bases exposes Beijing to other security risks, including becoming drawn into domestic conflicts in host countries.

Chinese nationals in Pakistan, for example, have been targeted by insurgents. Most recently on August 13, militants attacked vehicles carrying Chinese engineers in Gwadar, one of the places experts say China could be eying for military port facilities.

Nonetheless researchers at the Naval Research Academy in Beijing argued in a 2014 report that China’s maritime power must extend into the Indian Ocean “to support the expansion of China’s national interests.”

“A possible strategic point could be the Pakistani port of Gwadar, which was built with Chinese support,” the authors said, adding that given geopolitical sensitivities in the region, the development of “overseas supply and support points” should be “done cautiously and in a low-profile manner.”

While public discussion about overseas military bases has gathered momentum in China in recent years, there remain “higher military priorities” for the People’s Liberation Army, according to Isaac Kardon, a senior fellow for China studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace think tank in Washington.

“Chinese leaders perceive the most acute threats in maritime East Asia – Taiwan, South and East China Seas – and are unlikely to allocate major resources or leadership attention to far-flung outposts that serve limited strategic purposes,” he said.

Instead China may be likely to continue its preference for relying on “lower-end dual-use options” linked to its overseas commercial infrastructure, like ports, according to Kardon.

Still “there is a growing case for a few more military bases to support a more robust, higher-end presence,” Kardon said, adding that China will be “will be opportunistic about basing arrangements when they can be had.”

More than bases

While the bulk of attention on the PLA’s overseas ambitions focuses on naval facilities, it is also looking at facilities for eavesdropping and communications, according to the FDD – something other powers like the US are widely believed to operate in key strategic locations.

Sources told CNN earlier this year that China has been spying on the US from facilities in Cuba for years. A source familiar with the intelligence said Beijing also has a deal in principle to build a new spying facility on the island that could allow the Chinese to eavesdrop on electronic communications across southeastern US.

The FDD’s Singleton says the Cuban efforts show the extent of the PLA’s reach already.

“China’s deepening military and intelligence ties to Cuba reaffirms that the PLA need not establish regional military primacy in Asia as a precondition to project globally,” he said.

Singleton also points to China’s deep space ground station in Argentina’s Patagonian desert region, which Argentina said both sides agreed was “exclusively for civil purposes.”

The facility is run by the China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General Organization, which government records show is linked to the PLA’s Strategic Support Force.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank in Washington points out why that’s troubling to US military planners.

“Ground stations … help keep track of the tens of thousands of satellites and other objects in Earth’s orbit – a capability known as space situational awareness (SSA) that is critical for fighting and winning wars in information-rich battle spaces,” the CSIS said in a 2022 report.

The view from Washington

In Washington, some members of Congress are taking notice, and urging the Defense Department not to hesitate in taking measures to counter a growing PLA footprint, whether by enticing possible Chinese base hosts to look to the US instead, or by beefing up the US military presence in areas where the PLA is.

“The Chinese Communist Party will continue their strategic expansion of military bases across the globe with access to major sea lanes, maritime chokepoints, and oil and gas import routes,” Rep. Rob Wittman, a Virginia Republican, said in an email to CNN.

“The Defense Department must enhance its engagement with Beijing’s target nations to offer those countries the United States as a stronger economic and security partner,” he said.

Wittman’s colleague, Massachusetts Democrat Rep. Seth Moulton, told CNN that Washington should be getting more involved in countries where Beijing is trying to make inroads because it offers what China can’t.

“Our first response should be to double down on diplomacy because America offers freedom, security, and economic opportunity where China wants control,” Moulton said.

“China’s goal is world dominance through authoritarian control. And authoritarianism is what they are exporting to other countries and regions by expanding their military footprint.”

That view is echoed in the Pentagon.

“What is particularly concerning about (China’s) activities is the lack of transparency and clarity around the terms it negotiates with host countries and the intended purposes of these facilities,” US Defense Department spokesperson Lt. Col. Martin Meiners told CNN.

No comments:

Post a Comment