David Loyn

It is two years since the United States withdrew its troops from Afghanistan and ceded power in the land to the Taliban. Yet the Taliban’s control of the country remains fragile, and if its administration were to break up, there is a danger Afghanistan would become a failed state of feuding warlords and a crucible for terrorism. The international community is doing little to support a potential opposition to Taliban rule, something that should now become an urgent priority.

It is hard to know what is going on inside the Taliban. But a brief window into the internal tensions opened earlier this year when a number of senior figures, including Sirajuddin Haqqani, the acting interior minister, and Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, the acting deputy foreign minister, were filmed speaking out against the tight control by Hibatullah Akhunzada, the supreme leader who issues edicts from his base in Kandahar. The public expressions of dissent were squashed and Stanikzai left the country, but the tensions have not gone away.

The Taliban face a different country from the one they left in 2001, with a new generation with different aspirations

The principal division is between the Haqqani network, which controls Kabul and is strong in the capital and the east, and the Kandahar leadership in the south. The Haqqani network was founded in Pakistan and is backed by Pakistani intelligence. It has been formally allied to the Taliban for more than a decade, but the relationship is now strained.

Both sides have been courting loyal commanders. Hibatullah is said to have brought a

suicide bomber unit back to Kandahar for his added protection.

The Taliban have found it hard to adapt from being a guerrilla group to a government. Many ministries are headed by poorly educated clerics. While operating in the shadows for most of the past 20 years, the Taliban imposed control through intimidation – killing more than 10,000 tribal elders and religious scholars, according to one military source, and mobilizing opinion against the presidency of Ashraf Ghani, calling it corrupt and westernized.

In government, they wanted full control of the media. They allowed foreign correspondents into the country for their first year in office, but the issuing of visas is now rare. Widely publicized executions and the flogging of male and female ‘adulterers’ are acts designed to secure compliance through fear as well as displaying their tough jihadi credentials to recruits, who might otherwise join Islamic State-Khorasan Province, which has a growing presence.

Window of opportunity

On taking power the Taliban enjoyed a peace dividend amid relief that the fighting had stopped. The new Taliban state was accepted in 2021 by traditional tribal and religious leaders for want of anything better, as the republic collapsed. But that consent was conditional on delivering stability. And as time has passed the Taliban have provoked opposition to their rule by their failure to build an inclusive government, with few non-Pashtuns in any significant roles and no jobs for women.

Pashtuns are Afghanistan’s largest minority but form less than half of the population. The Taliban now face a different country from the one they left when driven from power in 2001, while a new generation with different aspirations, particularly among women, is more willing to end the cycles of violence that have marred the past 50 years.

One of the brightest stars to flee the country in August 2021, the filmmaker Sahraa Karimi, said: ‘Our generation wanted to create a new narrative for Afghanistan that promised construction, dynamism, hope and progress.’

The Taliban regime is offering something very different, with girls confined at home and boys educated along strict lines in madrassas. The window of opportunity to recover the values of the Afghan republic will not be open for ever.

Challenges of opposition

Just as the Taliban have found it hard to translate from insurgency to government, in a mirror image, those who were in government have struggled to build a coherent platform for opposition. There were some understandable problems. Afghanistan’s most competent people are scattered across the globe, focused on resettling their families, with many ending up on Canada’s west coast.

Afghanistan’s past brings its own problems as well. Political parties have been treated with suspicion for complex historical reasons, and there was no interest in developing them in the republican era after 9/11. Many of those recently in government were technical appointees. They had never had to deal with practical politics.

In traditional areas, people have been persuaded that democracy is a western construct, responsible for corruption

‘Democracy’ is a contested concept, treated with suspicion in more traditional parts of the country, where people have been persuaded that it is a western construct, responsible for corruption and mismanagement, and not applicable to their traditional Islamic culture. Reaching back further into the 1980s and 90s, the communist takeover backed by Russia and the mujahideen resistance which defeated it, both carry their own baggage.

One of the lost opportunities of the collapse of the republic was that 20 years was not long enough to neutralize the toxic potential of this history. The mujahideen leaders, often referred to as ‘warlords,’ are now mostly based in Turkey and could be an obstacle, although few expect them to retake power.

In building an opposition movement to the Taliban there are inevitable tensions between activists inside the country and those outside. A number of women’s groups have spontaneously emerged inside Afghanistan since the fall of the republic.

Shaharzad Akbar, the former head of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Council, has been tracking these groups from Britain, and says they want a harder line from the international community: ‘They are very specifically asking for non-recognition of the Taliban.’ They do not have the benefit of western funding and are resentful of the NGO activists who received that funding in the past and have now fled.

There is no way that you can take back power from the Taliban without military pressureNargis Nehan, prominent women’s activist and former government minister

The most promising track to build a coherent opposition outside is the Vienna process, which has seen two conferences in Vienna and one in Dushanbe, and set up a working group to create a ‘single national umbrella organization’ against the Taliban. This process, and other meetings of the Afghan diaspora, have been supported by foundations and private funding, with no government involvement.

When international envoys from more than 20 countries met the United Nations Secretary-General in Doha in May to discuss Afghanistan, there were side meetings with the Taliban, but no attempt to engage non-Taliban opposition groups. There is a paradox that the international community is able to ignore an Afghan opposition that lacks coherence, while doing nothing to create it.

Some of the key movers in building an opposition are the network of ambassadors of the republic, many of whom are still in their embassies. One of the most effective, the Geneva ambassador Nasir Andisha, said it is going to take time to build a coherent platform, with a need for participants to understand the mistakes that led to the collapse of the republic. ‘I think they could never be in opposition,’ he said, ‘if they do not really have a deep-down reflection.’

The failure of engagement

Two years on it is clear that the Taliban have no interest in giving in to demands for a less repressive government, so the current engagement is not working. The US, Britain and the European Union have all publicly stated that they will not back armed resistance against the Taliban, and that was one reason for their lack of support for the Vienna process. But Nargis Nehan, a prominent women’s activist, and former government minister, said: ‘There is no way that you can take back power from the Taliban without military pressure.’

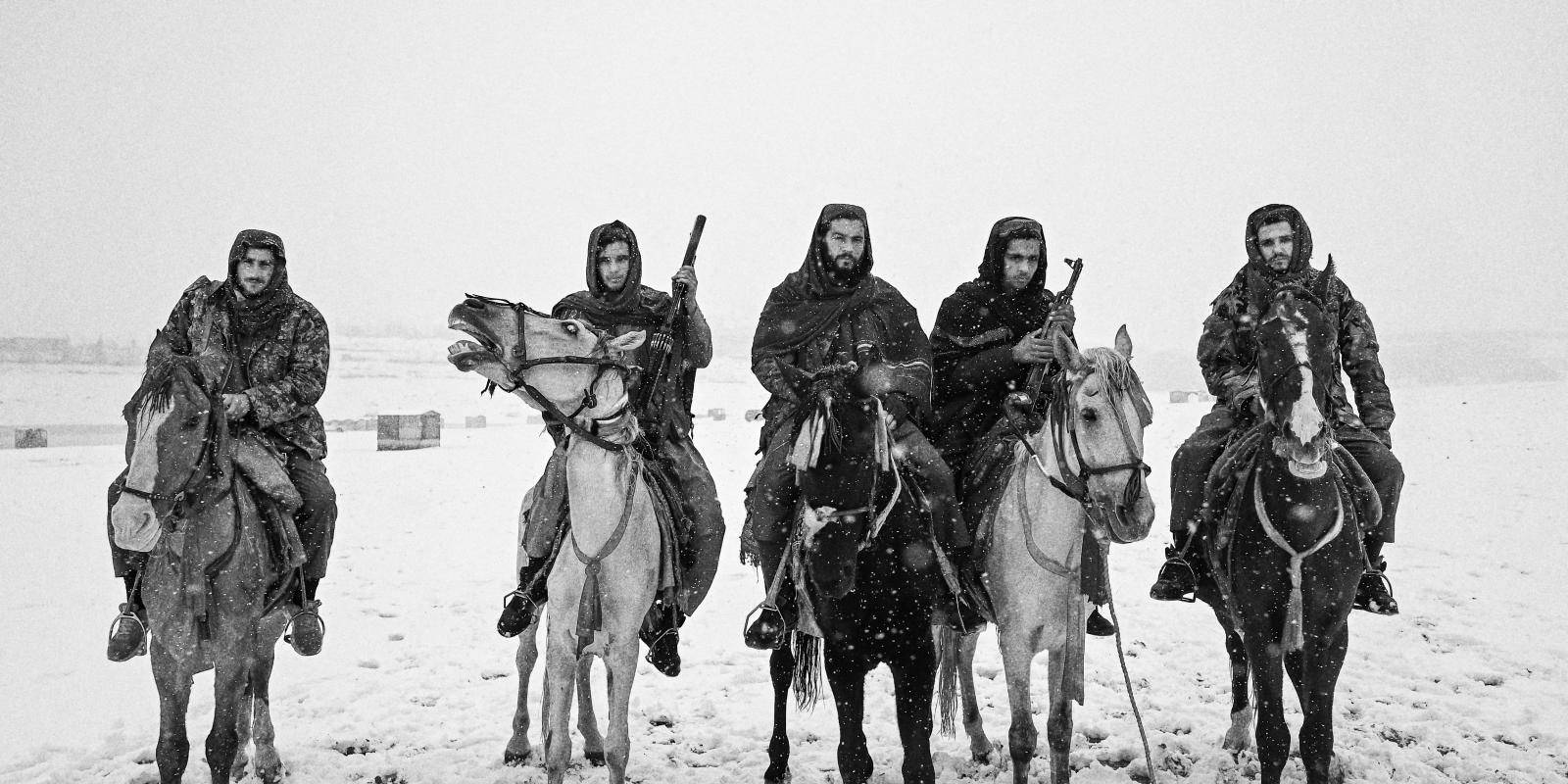

Ahmad Massoud, the commander of the most prominent anti-Taliban armed group, the National Resistance Front, was at both Dushanbe and Vienna. His father, Ahmed Shah Massoud, who was assassinated on the eve of the 9/11 attacks, was the most successful mujahideen commander in the insurgency against Russian occupation in the 1980s.

Apart from the NRF, which has been fighting, with some effect, in the Panjshir Valley northeast of Kabul, Yasin Zia, a former Afghan army chief of staff, has also had success in guerrilla actions, including targeted assassinations. Sami Sadat, another former Afghan general, has spent most of 2023 in the US, building support among veterans’ groups for a fightback.

We have reached a point where the Taliban dictate the terms of the EU’s engagement with the democratic oppositionNasir Andisha, Afghan ambassador to Geneva

The Taliban reprimanded Tomas Niklasson, the EU envoy in Kabul, after the Vienna meeting because of the presence of armed groups. But this should be robustly ignored. As well as acceding to Taliban demands not to support armed opposition, the West is also allowing the Taliban to dictate the terms by its focus on women’s rights rather than a wider agenda, such as the Taliban failure to deliver an inclusive government with representation from Afghanistan’s many ethnicities, or their backing of Al-Qaeda.

Women’s rights are clearly an urgent priority. UN agencies in Afghanistan are now operating outside their mandate by acquiescing to the Taliban ban on women workers in April this year. This does need to be resolved.

But the issue has taken all the oxygen in the room, according to Manizha Bakhtari, the Afghan republic’s ambassador to Vienna: ‘It is very important and significant, but it is a softer thing to discuss than the links between the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. I believe the world should consider all these problems together.’

It suits the US administration not to discuss the Al-Qaeda connection. Washington does not want reminders of the chaos of withdrawal, preferring to focus on the Taliban’s offer to work against terrorism. On June 30, President Joe Biden made a frankly delusional unscripted aside at a press conference: ‘Remember what I said about Afghanistan? I said Al-Qaeda would not be there. I said we’d get help from the Taliban. What’s happening now? What’s going on? Read your press. I was right.’

Between reality and the wishful thinking of the Biden administration, a coherent American approach is not likely to emerge soon

Only four days earlier he could have read a headline that did indeed show what is happening now: ‘Taliban Flouts Terrorism Commitments by Appointing Al-Qaeda-Affiliated Governors,’ referring to a UN report showing that links between the two organizations are ‘strong and symbiotic,’ and Al-Qaeda is ‘rebuilding operational capability’ from its base in Afghanistan.

The UN report could not be clearer: ‘Promises made by the Taliban in August 2021 to be more inclusive, break with terrorist groups … and not pose a security threat to other countries seem increasingly hollow, if not plain false, in 2023.’

Given this disconnect between reality and the wishful thinking of the Biden administration, a coherent US approach is not likely to emerge in the short term.

Alternative paths

But the West is not America. And there is an opportunity, for not much cost, for other countries to support a potential Afghan opposition movement and the civil society and media it will need to develop.

International donors are believed to send around $40 million a week to Kabul, although precise figures are not publicized, and governments should be able to ensure it is going where it should while at the same time looking to potential political actors other than the Taliban. This can be done while maintaining purity by not supporting armed activity. But there has been little interest to help emerging leaders.

Al-Qaeda is so bound up in government that its training manuals are used in the Ministry of Defence

Another effort to build a civic platform for dialogue between Afghans, including the Taliban, is being explored by the European Institute of Peace, under Michael Keating, its executive director. But while this is specifically non-violent, it has been difficult to attract funding for it.

Nobody thinks this is easy. There are so many different interests among non-Taliban Afghans that a united platform would be hard to achieve. The women’s activist Nargis Nehan said that supporting several initiatives may be the best way forward: ‘By putting all these small drops together,’ she said, ‘we will bring on board a good number of diverse opinions.’ There are innovative ways to fund local activists without having to go through Kabul, she said.

The alternative is that regional players, most notably Russia, China, Pakistan and Iran, will try to build their own client bases. They have lost any illusions that they can deal with the Taliban, and all face potential threats from movements based in Afghanistan. The UN report found that about 20 insurgent groups are now operating under the Taliban, with Al-Qaeda so bound up in government that its training manuals are used in the Ministry of Defence.

The anti-Chinese East Turkestan Islamic Movement is being given sanctuary and poses a ‘serious threat to Central Asia in the longer term.’ The anti-Pakistan group Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan has a ‘tightly bonded’ relationship with the Afghan Taliban. Mohammad Reza Bahrami, the former Iranian Ambassador to Kabul, tweeted that the ‘inevitable deepening of internal rifts between the Taliban factions’ made recognition less likely.

All these countries are now looking for alternative paths for Afghanistan. If Taliban infighting increases early next year as stocks of opium run down after the ban on planting poppies, then local commanders could take things into their own hands.

We have seen this play out before in the early 1990s, when the country was torn by rival warlords after the Russian withdrawal. The West has the opportunity to shape a different future for Afghanistan this time.

No comments:

Post a Comment