Tim Fernholz

The point of putting a sensor in space is to gather data about the Earth—that’s where everybody is, it’s where all the money is, and so there is an industry of companies whose satellites are imaging the Earth in various ways.

The point of putting a sensor in space is to gather data about the Earth—that’s where everybody is, it’s where all the money is, and so there is an industry of companies whose satellites are imaging the Earth in various ways.As space becomes more economically important, and with the number of satellites rapidly increasing, there’s a lot more interest in pointing those sensors away from the planet below—at other spacecraft, at debris in orbit, at potentially dangerous asteroids, even at the Moon. You may have noticed that you rarely see a picture of a spacecraft in orbit—it’s either an image from the factory floor, or a computer rendering. That’s about to change.

Maxar, a corporate descendent of the first private Earth observation company that was taken private by Advent International earlier this year, is rolling out a new business line called non-Earth imagery, or NEI, doing exactly that. The company has offered the service to the US government for several years, but only obtained a license from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to sell the imagery to private buyers and allied governments in August 2022.

Traditionally, the US hasn’t allowed companies to collect imagery of spacecraft, so that it can hide the designs and capabilities of its own satellites from potential rivals. But in a world where Russia and China are capable of sending inspection satellites to check out American spacecraft, it doesn’t make much sense to hold back the industry anymore. Now, in an effort to leverage the advances made by the private space sector, the US government is rolling back restrictions on all kinds of precision sensors in space. Besides being able to take pictures of other spacecraft, NOAA has now lifted restrictions on things like high-resolution space radar imagery.

Kumar Navulur, a senior director at Maxar, led the team that figured out how to adapt the satellites for non-Earth imaging. The biggest challenge is pointing the spacecraft accurately. Maxar needed to develop new software to help predict conjunction points in orbit—when their spacecraft will be optimally positioned near a target to capture an image of it. That’s trickier with objects in space than objects on the Earth, since Maxar’s satellites always know how far they are from the planet when they observe it but don’t know exactly how far away another spacecraft or a piece of debris is.

What satellites see when they’re not looking at Earth

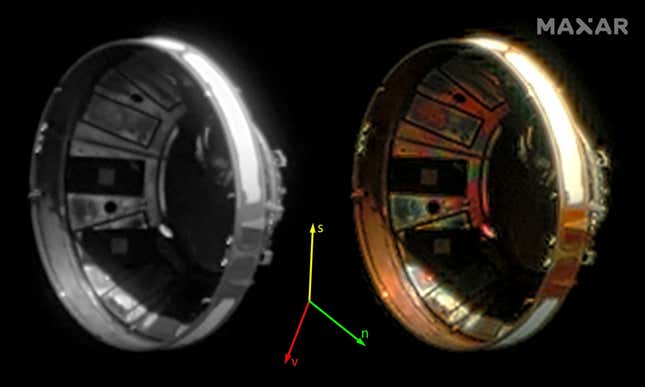

Navulur says there are several different applications for the new product. One is inspecting spacecraft for potential damage. One of Maxar’s own satellites, WorldView-2, suffered damage from space debris in 2016. Other times, spacecraft suffer problems when solar panels and other components fail to deploy correctly after launch, or if it starts tumbling in an unexpected way. An image from Maxar could help other satellite operators better understand their vehicles on orbit.

An image of NASA’s Landsat 8 taken from 94 kilometers away.Image: Maxar

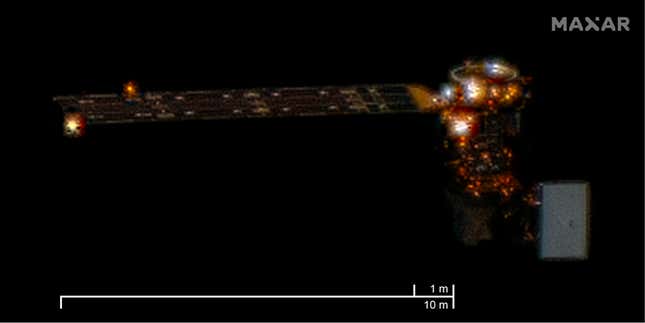

Another use case is space situational awareness, a growing concern as tens of thousands of new spacecraft are expected to be launched into orbit in the years ahead. Right now, the US government is developing plans to better monitor the environment around the Earth, an effort that will require multiple sources of data, from ground-based radar to trackers in space.

Imagery of a Japanese rocket fairing abandoned in Earth’s orbit.Image: Maxar

Maxar’s orbital sensors can help confirm that satellites are where they are expected to be, a potentially useful service given that most satellite locations are based on calculating orbital dynamics, not real-time observation. Wide-field imagery that isn’t focused on a single satellite could still allow users to identify and locate multiple spacecraft or pieces of debris. There’s also the intriguing possibility that Maxar could capture the often-chaotic deployment of dozens of spacecraft during rideshare missions like SpaceX’s Transporter series. Navulur suggested that though Maxar’s license allows it to capture any images it likes, the company wouldn’t share imagery of private spacecraft without their owner’s permission.

An image of the International Space Station captured from 314 km distance.Image: Maxar

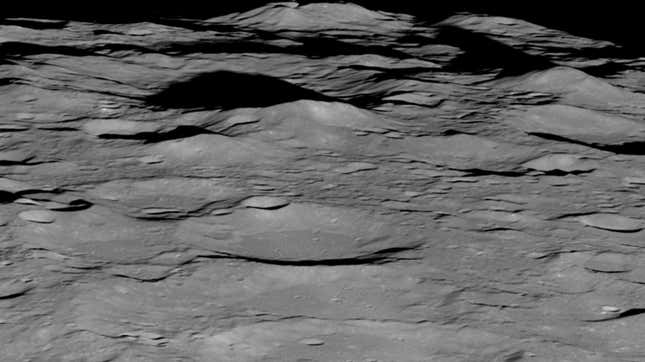

This imagery could also help track potentially dangerous near-Earth objects. NASA is still working to launch an infrared space telescope to spot incoming asteroids, but in the meantime, additional sensors can help provide more coverage. Though visual-wavelength images aren’t great for determining the size of objects, it does allow them to be located, even at long distance. Here’s a shot of an asteroid, NEO 2015 TB145, that the satellite captured in 2015 when it was less than half a million kilometers from Earth.

No comments:

Post a Comment