RYAN PALLAS

When the all–volunteer force turned fifty last month, civilian and military leaders called it the most challenging environment since the force’s establishment in 1973. Amidst the ensuing discussion about how to solve the nation’s military recruiting woes, many people have suggested that a return to mandatory national service could help. Often, they imagine that conscription could fix the challenges facing a country they see as less fit, less patriotic, and less eager to serve than previous generations.

Unfortunately, contemporary debates about conscription often rely on a distorted understanding of its history. Over the past 250 years, the nation has generally used conscription sparingly. Whatever the benefits or drawbacks of reintroducing the practice today, this historical experience suggests that it is unlikely to be a panacea for the country’s problems. As military historian Brian Linn put it, “Nostalgic references to a golden age where Americans were fit, patriotic, and motivated have been a staple of Army lore for well over a century, but they hardly reflect historical reality.”

Being Selective with Selective Service

During the Revolutionary War, the colonies depended upon militias comprised of “raw untrained troops, for the very good reason that none others were available, except in paltry numbers.” The “first scheme of mobilization” was instituted on July 18, 1775, and the Revolutionary War was “fought by a Continental army that was staffed in part by a militia draft.” After this, the nation saw the first national conscription act passed during the Civil War. If one investigates further, it was not President Abraham Lincoln who initially did this, but rather Jefferson Davis and the Confederate Congress in April 1862. It would not be until March 1863 that a National Conscription Act was passed by the United States.

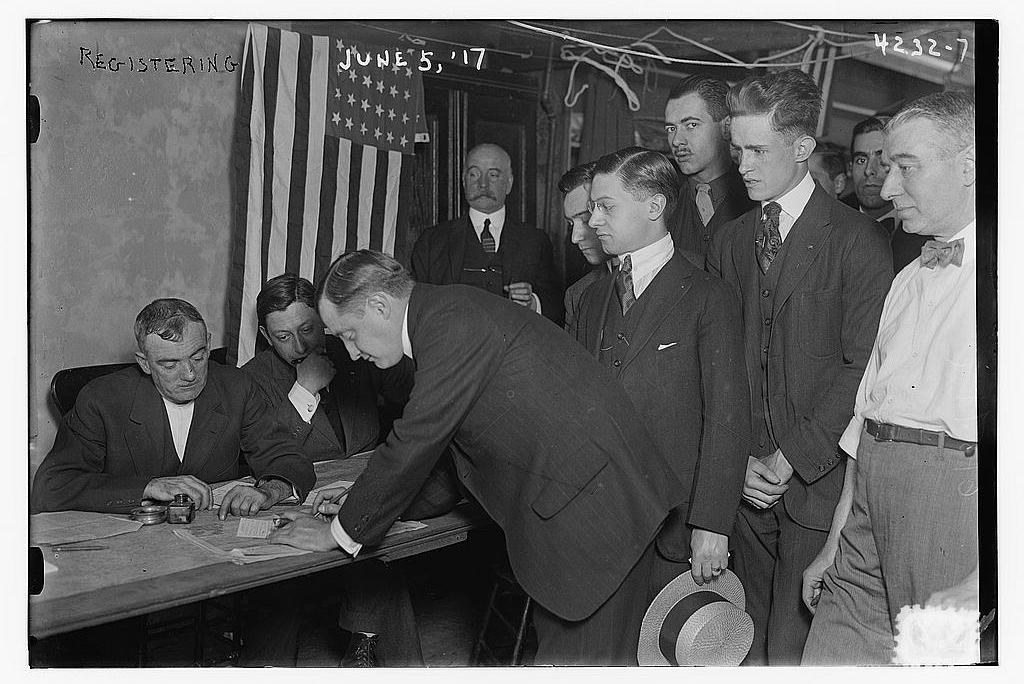

The establishment of the Selective Service, the agency responsible for instituting the military draft, occurred in May 1917 and received widespread public support. Prior to World War II, lawmakers foresaw a rising need for increased personnel levels leading to the first peacetime conscription law in 1940. At the conclusion of World War II, the United States continued to see the need for a peacetime draft and in 1948 again reintroduced it after President Harry S. Truman had ended it the year before. This trend toward peacetime conscription was aimed at providing adequate personnel levels necessary for the Cold War. The U.S. Army has remained the largest consumer of conscripts, more so than any other service due to its historical manpower challenges. In this context, the benefits of conscription were “a steady and sufficient number of recruits at low cost in salaries and benefits.”

Between 1951 and 1967, Congress repeatedly voted to extend conscription with little opposition. Then, as the United States navigated Vietnam, senior military leaders began to increasingly present the practice as the country’s historical default. As a result, when the all-volunteer force was established in 1973, it was easy to forget that this “marked less of a rupture with custom than a remembrance of a venerable practice.” In fact, America “only relied on conscription to field an armed force four times: the Civil War (1863–1865), World War I (1917–1918), World War II (1940–1945), and the Cold War (1946–1947 and 1948–1973), a total of 35 years.” Some quick math shows this only amounts to 15 percent of the country’s existence.

Old and New Concerns

Not only has conscription seldom been the norm, but American and European history offer further warnings against viewing it as a panacea. Consider the verdict of historians on the use of conscription during the Napoleonic wars. After the country’s revolution, France’s citizens rallied around calls for mandatory military service, or the levée en masse, which provided the French government with an endless supply of personnel. This “enabled the French commandeers to fight more aggressive and costly campaigns, and to fight more of them.” Whatever the short-term benefits, France ultimately paid the price for this approach.

Despite emerging victorious in its wars with France, Britain also faced problems regarding conscription. Bernard Rostker, one of the foremost experts on U.S. military personnel policy and an Army officer who served during a time of conscription, argued that, in Britain as in America today, it was “the romantic and utopian who longed for the conscript force of citizens.” By contrast, he concluded that the transformation to a standing professional army was “inevitable” on account of broader historic trends. In short, “it was the practical consideration that a conscript force could no longer produce a viable military institution that moved England toward a professional military.”

Tellingly, it was frustration with the British practice of conscription that helped drive early American leaders’ resistance to the practice. Describing impressment into the Royal Navy, Benjamin Franklin wrote: “The question then will amount to this; whether it be just in a community, that the richer part should compel the poorer to fight for them and their properties for such wages as they think fit to allow, and punish them if they refuse?” Franklin, for his part, concluded that while the practice might be legal, “I cannot persuade myself it is equitable.”

In addition to these historical precedents, conscription would face greater challenges today, even if it was conducted more elegantly than British impressment. Rostker recently commented that calls for conscription fail to account for the small percentage of personnel the policy would actually be required to provide. Where many see an idealistic policy in which hordes of able-bodied men report for mandatory service, their arguments fail to account for the increased costs, logistics, and personnel requirements to process and train such a force. Thus, calls for a return to conscription become more about reviving an imagined past than responding to the concrete needs of a modern military establishment.

Arguments in favor of conscription also fail to consider that of the available population, the military requires only a fraction of a percent of total eligible males. History reveals a similar situation where “the size of the eligible population of young men reaching draft age each year in the 1960s was so large and the needs of the military so small in comparison, that in practice, the draft was no longer universal.”

Calls for conscription also fail to include women, half of the national population and a majority of those with higher education levels. The male-only draft was upheld on June 25, 1981, by Justice William Rehnquist on the grounds that women could not participate in combat-related functions. This argument no longer holds, as Secretaries of Defense Leon Panetta and Ash Carter opened combat-related positions and all military occupations in 2013 and 2015 respectively. What’s more, a 2019 district court ruling declared a male-only draft unconstitutional.

Conclusion

History cannot tell us if reintroducing conscription is right or wrong. But it reveals that this policy has been the exception throughout the nation’s existence. A historically informed approach to supplying the personnel levels the U.S. military needs might begin with examining the anachronistic personnel policies, largely derived from World War II, that remain in existence today. These include a failure to acknowledge the incongruence of military service and modern families, shifting family forms, archaic promotion schemes, outdated pay tables, and frequent relocation. A new study on military service could also include some of the factors that the original Gates Commission ignored in 1973, including the role of women and families. This could provide a basis for more lasting and meaningful change to enhance military effectiveness going forward.

No comments:

Post a Comment