Pradip Kumar Datta

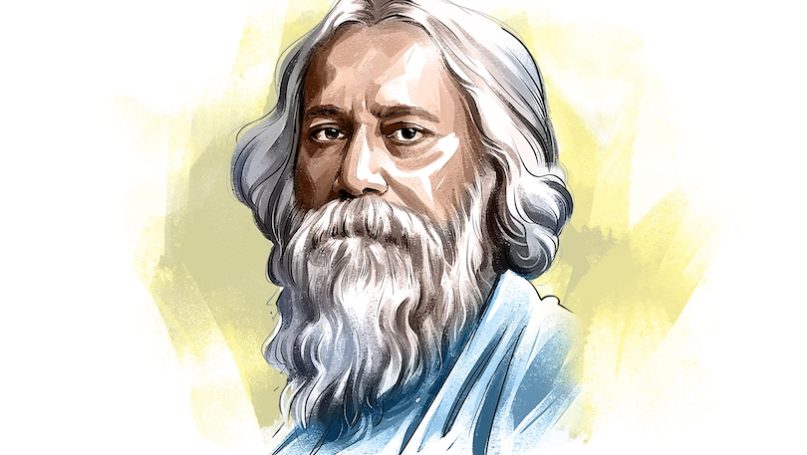

Rabindranath Tagore lived between the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. He was and remains an iconic figure in the Indian subcontinent, especially in its eastern part. Besides being the first Asian to get the Nobel Prize, he was not just a poet, a composer and novelist, but also a playwright, actor, short-story writer, artist, peace activist, who also founded a global university. In addition, he was an original thinker. Born in 1861, a few years after the 1857 rebellion and the establishment of Her Majesty’s Government, the young Tagore grew up in conditions of Hindu cultural revivalism and contributed actively to it as a young person. This was to culminate in his celebration of Vedic ethical norms and then later in a whole-hearted involvement with what is accepted as the first popular movement against colonial authority. I am referring here to the Swadeshi movement that took place in the first decade of the twentieth century (see Sarkar 1973). Side-by-side Tagore also inherited a faith in the universalism of Vedantic ideas from his family. This was based on a conviction in the omnipresence of Brahman, which can be defined as an essential presence that permeates all of creation as well as the individual soul, which is cosmic and acosmic, the origin and the infinite. It is possibly the belief in spiritual universalism that made Tagore receptive to the sense of ‘global’ existence. Born in a wealthy family with immense cultural capital, Tagore also travelled to England as a youth. The journey allowed him to experience the global as a habitation that was based on differences. The youthful journey presaged his later years when he travelled across the globe to about twenty five countries, as a public intellectual spreading a message of global peace and cultural interconnectedness.

Idea of the Nation

Swami Vivekananda and many others after him found in the idea of a Hindu Nation, a mark of cultural distinction and pride in a colonised world. Tagore, however, walked a parallel and more problematic path. Tagore emerged as an exceptional public intellectual who felt the effects of British colonialism deeply, not just on his country but on the world as a whole. He protested against Britain’s greed for territory and resources through the wars she waged against the peoples of China and Southern Africa. The wave of popular patriotism in England that supported the British repression of the Boers in South Africa was a tipping point for Tagore (Datta 2007). It paved the way to make him uncompromisingly critical of the idea of the ‘nation’.

In his early discursive writings during the turn of the century, Tagore drew on Renan to define the nation, only to dismiss it as a concept-word that was foreign to India. The nation for Tagore was the way that the Western world produced a singular and homogenous unity for itself. Tagore appears to have identified nationalism with colonialism in this period. In his poetry, he defined the nation through tropes of destruction and all-consuming fire. But together with this critique, Tagore retained a sense of cultural distinction. In this period, the commitment to cultural distinction led him to share much of the discourse of Hindu nationalism. He held society or samaj to be the basis of unity and invoked the myth of a Vedic past based on a respect for poverty, humility, and sense of kinship. The Vedic was a counterpoint to the materialism and destructiveness of the West. In formulating his project in these terms, the idea of society/samaj brought together the themes of sacrifice with that of extended community and rejection of the colonising West. However, the combination of these elements made his notion of the ‘social’ analogous to the concept of the nation.

Indeed, Tagore had reached an ideological crossroads. The incipient strands of Hindu nationalism could have developed into a full-blown Hindu exclusivism. This was certainly a possible option given the fact that at a time when the Swadeshi movement gathered steam and drew the middle and upper classes to itself, it was interrupted by the outbreak of Hindu-Muslim riots. Surprisingly, Tagore reacted in an unconventional way to the riots. For Tagore, these riots demonstrated the explosive reaction to the upper caste Hindu custom of treating Muslims as untouchables; in general, this was also a trait that he had noted in British colonialism, namely its propensity to separate itself from its others and engage in violence against them. It was something that was repeating itself in an anti-colonial movement. While this trajectory of self-reflection initially made him – in his novel Gora (1909) – critical in general of the idea of exclusivist identities whether of Hindu nationalist orthodoxy or Hindu reform (see Datta 2002), it developed into a global critique of the dominant strand of modern life itself.

Rocked by the outbreak of the Great War (1914-1918) between mutually competitive colonial powers of the West, Tagore now developed a global critique of the idea of the nation. The war led him to critically conceptualise the idea of the nation that arose in the west but now threatened to hegemonise the countries of the East. In short, the nation was the dominant way of organising global humanity. He elaborated his critique in the Nationalism lectures (see especially Tagore 1994) and in The Home and the World (Datta 2002), his novel about Hindu nationalism. It is not surprising or coincidental that these works were composed in 1915-16, during the middle of the First World War, an international conflict of nations that confirmed the worst fears of Tagore. Let me turn here to his critique of Nationalism.

Critique of Nationalism

To Tagore, the modern global condition was one in which cultures and peoples were coming closer. This proximity raised a problem. It made the issue of difference, an urgent and critical one. Instead of finding ways to live with differences that populated the globe, the nation converted differences into antagonisms by producing both external and internal enemies. At the heart of the nation was an ethical violation of human relationships. The nation organized entire peoples into mechanical organizations brought together by common political and economic interests. The purpose of the nation was to accumulate resources and territory. Society itself was converted into a resource. It became an object of control while human relationships became instruments to serve the nation. The foundation of the nation was supplied by the principle of competition. Tagore did not rule out the importance of competition. But in pre-modern times, while the principle of competition was always present in social organizations, it existed as a subordinate element in society. Society/samaj was based on ethical values that subjected the principle of competition to its own ends. Competition was confined to certain economic activities.

Over time however, the process of competitive accumulation, that is the acts of vying with one another for possessions, expanded its sway to cover the entirety of society itself. It became the organizing principle of society. This was also a process that demanded more and more efficient levels of organizations to maximise resource extraction and utilisation. The outcome of this was the establishment of a new principle of collective life. This was the nation. Two global outcomes followed. Firstly, the nation became more than just a business corporation. It generated a transcendental, god-like aura around itself. Secondly, competitive accumulation led nations into war as these nations competed for resources and territories. The nation became a new god. It generated a religion that motivated an entire people to be willing to kill and to die.

Tagore’s critique of the nation as a global phenomenon required a move to universalist and globally-oriented thought. The world war had led to widespread jingoism in every country of Europe. But it had also mobilised a few but influential thinkers and peace activists there, who strenuously objected to the war. Tagore joined this group that included intellectuals such as Bertrand Russell and Romain Rolland. With them, Tagore became a co-signatory to what was grandly called Declaration of the Independence of the Human Spirit. This was a global manifesto for international solidarity and global peace (Andrews 1945, 20). It is interesting that the despair at the Great War led Romain Rolland to visualise the importance of educating future generations in peace. The enterprise of education was something in which Tagore was already engaged from the beginning of the century. So, instead of visualising the future, Tagore expanded his existing experimental school into Visva-Bharati that is popularly described, although with some inaccuracy, as a world university. But I am anticipating my story.

While Tagore was a universalist, he was a qualified believer in it. It may be recalled that in his early career, Tagore veered towards Hindu nationalism but then moved away from it. But this did not lead him to repudiate his identity as a Hindu. However, Tagore re-defined identity itself. For him, identity was not a name with some attributed characteristics that was designed to distinguish and pit one group of people against other collective identities. Accepting the identity of a Hindu did not mean that he saw it as counterposed against Islam and Christianity. Instead, identity for Tagore had open boundaries (Sen 2014). Let me explain further. Identity in the sense of belonging to a history and to a people was not just inevitable but also necessary. Without different identities there would be a ‘colourless cosmopolitanism’. Indeed, we can see the suspension of differences would make the global a homogeneous place where people need not interact for everywhere they would be the same. Instead, identity needed to be held but in way that would make it open to interactions with other identities. Hence identity would be like a “blank cheque”, containing just the name, its place and time, but with its contents constantly being changed by interactions with others. This also meant that the universal was not a given. It had to be produced through constant and widening arcs of interactions with people who were strangers and others.

It is the process of constant interaction that was sought to be institutionalised in Visva-Bharati. The latter was based on interactions between student and teachers, between middle class intelligentsia and rural peasantry, between students of different provinces of India and finally and possibly most significantly, interactions between peoples of different nations and regions. Interaction itself was conceptualised as the notion of cooperation, that is, institutionalised activity that brings people together to produce new relationships, cultures and improved material life.

Tagore gave a great deal of importance to work. He believed that any idea got its final shape by work; it was work that showed the possibilities and limits of any idea. This makes it necessary to conclude the story of Tagore’s thought by a quick glance at the practices of Visva-Bharati. But before that I will dwell at some length on the essay I have referred to, that is The Religion of Man. This was delivered as a lecture at Oxford in 1930, nearly a decade after the founding of Visva-Bharati. This essay contains some of the key philosophical ideas that underpin Visva-Bharati.

The Religion of Man

While The Religion of Man offers a wealth of ideas and experiences, two concepts in particular demand attention (Tagore 1996). The first is the idea of Cooperation. Tagore begins by proposing an atomistic idea of creation. According to this conception, the world begins as atoms that come together and then mutually coordinate to acquire form and life. Cooperation between atoms then supplies the basis of creation and evolves and develops into human life and its human interactions. Together with cooperation is the exceptional status of the human. This comes from the human capacity to generate surplus. For Tagore, surplus means the capacity to overcome limits and constraints. The human begins by standing on two legs which indexes man’s capacity for transcending limits, in this case, the constraints of its biological nature that would have condemned him to use four limbs to move. By human, Tagore does not mean purely individual capacities, but those of society as a whole. Individuals realise themselves in their relationships with others instead of being caught up in the prison house of individual interest. Thus, agriculture is the first activity in which humans come into their own, for they work together in cooperation. In short, ‘surplus’ is the capacity of human beings to continuously transcend their limits through ‘cooperation’.

The universalistic orientation of The Religion of Man provides the grounds, as mentioned before, for the practices of Visva-Bharati. I will briefly relate two of these. The first is the idea of cooperation as ‘cultural exchange and intermingling’. For Tagore, India consists of several traditions of thought which were dominantly religious but also included folk and vernacular traditions. All these were needed to be brought together and consolidated. It may be observed that the streams of Indian thought which Tagore identified also included Western traditions. For Tagore, these elements were scattered. They needed to be consolidated through a free exchange of interactions so that India could then gift the best of her traditions to the West. This was not to be an India that regarded its Vedic past as a model for the present and future. Instead, India was seen as an entity that was evolving through a process of internal exchanges leading to an unknown horizon of the future where yet another round of work would start in interactions with the West. Of significance here is the distinction – and the overlap – between the East and the West. India is no pure space of thought. It already includes the West (and Islam and many other traditions besides classical Hinduism). On the other hand, the West is seen to have some of its constitutive elements from the East, for instance, the teachings of Christ. Cultural distinctions are not stable nor are they incommensurable. They are generated by different processes, of specific interactions in time and space.

The principle of cooperative surplus works not just at the plane of thought among different cultures of the world, but also in the other, internal space of division, that is, between the ‘City’ and ‘Village’. Cooperation is also embedded in the materiality of work undertaken in specific communities. Visva-Bharati was also premised on the assumption that education was not just a matter of generating new ideas. It had to also produce new forms of material and social life. This was to be done by remaking village life so that it would work on principles of cooperation. The world of village India was an individuated and litigious one. Hence one of the key tasks of Visva-Bharati volunteers was to organise rural inhabitants and make villages self-sufficient. Middle class volunteers (with urban backgrounds) would act as co-workers who would help remove the villagers from the chain of dependencies – whether these were on money-lenders, the vagaries of nature or indeed the middle class activist. All this could come about if villagers learnt to cooperate through institutions that promoted this objective. I should note that Visva-Bharati generated multiple modes and levels of cooperation (see Sinha 2010 and Datta 2015). This was all directed towards producing what I call an ‘existential surplus’ that would address the differences and divisions of the world and generate mutual conversation and exchange.

What does Tagore’s project tell us about the search for distinction and universalism? It may be remarked that Swami Vivekananda resolved the problematic relationship between cultural distinction and universalism by claiming that the distinction of Hinduism lay in its spiritual universalism as well as in its capacity to absorb other religions into its scheme of life. Tagore’s notion of cultural distinction does not tread the path of Hindu Supremacism. Instead, it takes the different route of co-operation. The idea of cooperation was one that Tagore had encountered in the writings of George Russell, an Irish nationalist and member of the Irish literary revival. While Russell’s book The National Being had sought to theorise the global implications of rural co-operators, Tagore extends it into a philosophical principle that carries resonances of the atomistic philosophical traditions of Vaisheshika, one of the schools of Hindu philosophy, even as he harnesses this into his own conception of an infinite human surplus. Further, as I have tried to show, Visva-Bharati disaggregates cooperation into a multiplicity of practices that inhabit different kinds of worlds that make up the ‘Global’. Tagore’s idea of cultural distinction is not a stable one. It is open to constant change and re-inflictions by different ideas from other cultures.

I want to end with two observations. The first is that Tagore’s career demonstrates a process of moving away from the field of religious nationalism as the grounds of cultural distinction to a secularised version of religion which he called the religion of man. The second is the idea that instead of searching for a single universal principle that could organize global life, Tagore is committed to universalisation as a process. The emphasis on an open-ended but globally interrelated multiplicity of process distinguishes Tagore from the traditions of universalism whether derived from Vivekananda or from the Enlightenment. Nor is it identifiable with the theories of deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation that envisaged the global as a singular space of multiple flows and interactions. Instead, Tagore’s thought conceptualised boundary making without a corresponding territorialisation. What this meant was an open notion of cultural boundaries that would retain its selfhood without insisting on a hard definition of what constituted the cultural character of a nation or a people. It was the selfhood developed and changed in different ways through the specificity of its history; which was also the history of interactions with other dynamic collective selves. It is in a wager on this process that Tagore finds a ‘Global’ belonging, one that did not need to be facelessly cosmopolitan or draw the global into becoming a battlefield of cultural universals.

No comments:

Post a Comment