Mackenzie Eaglen

A U.S. Air Force F-35A Lightning II fighter aircraft, assigned to the 421st Fighter Squadron, Hill Air Force Base, Utah, prepares to join formation while en route to Turku, Finland, June 13, 2019. The F-35A flew alongside two Finnish F-18 Hornet aircraft as part of a Theater Security Package. (U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Jovante Johnson)

U.S. President Joe Biden’s decision to send cluster munitions to Ukraine is important, but it has served up yet another reminder that the U.S. is short on stuff that blows up. Responding to reporters’ questions about the decision to send those shells, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said, “We need to build a bridge from where we are today to when we have enough monthly production of unitary rounds.”

Building a production and manufacturing “bridge” for munitions and mines takes time. These lines and workforces are not light switches that can be turned off and on quickly. From the consolidation of firms and suppliers, to long lead times for parts and energetics, and a number of other issues in between, our inability to produce munitions at scale has numerous causes.

Funding Woes

Dig a little deeper, though, and it is clear that money is the main reason the munitions industrial base lacks surge capacity. And like so much else when it comes to the state of our military today, the insufficient funds are no accident.

When past defense budgets did not provide for real growth, policymakers often allowed munitions to take the hit, choosing to support other underfunded accounts. Flying hours, munitions, sustainment, and workforce are regular bill payers for other defense priorities, according to Pentagon acquisition chief Bill LaPlante.

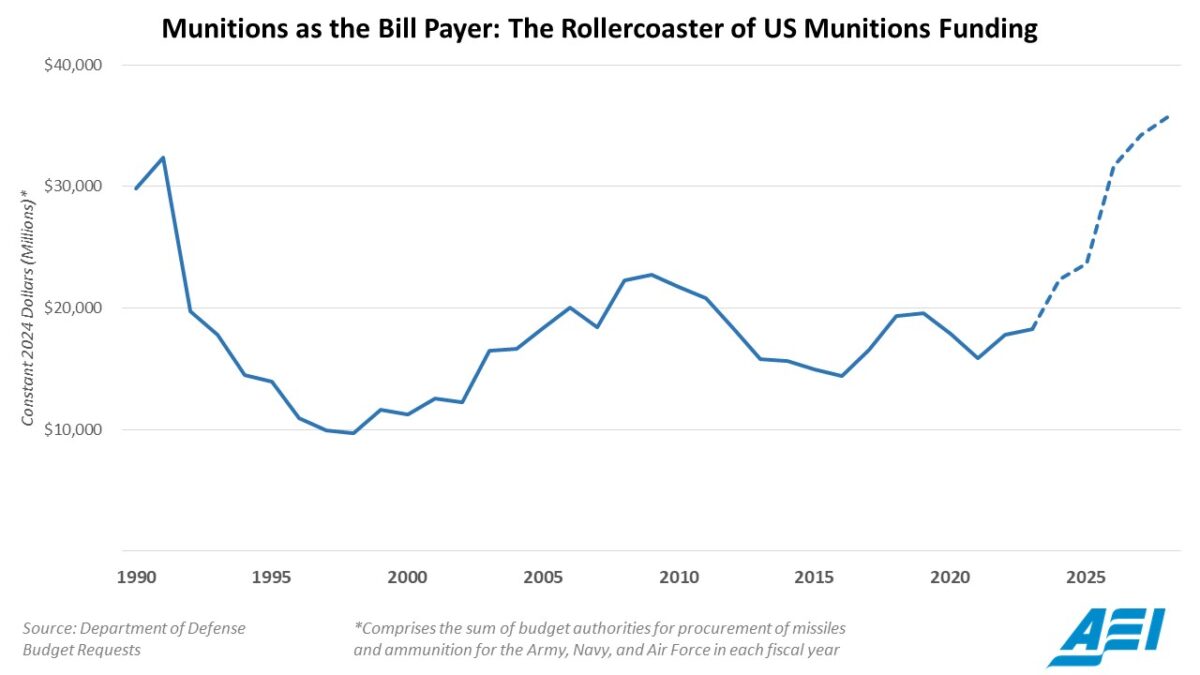

The result is munitions funding — and therefore production — that has come in waves. From over $30 billion at the end of the Cold War, funding fell to around $10 billion during the so-called procurement holiday of the 1990s, and it sits just under $20 billion today. There has not been for decades a sustained and steady increase in how much we spend on the things that give our planes, tanks, and ships firepower.

In a smaller snapshot of the above graph’s timeframe, Eric Lofgren found that between fiscal years 2011 and 2020, Congress tended to “cut roughly 40 percent of all munitions procurement line items.” That creates a lot of unpredictability and uncertainty. It makes industry suspect that this moment of support for Ukraine and Taiwan is just another episode of Lucy pulling away the football when it comes to promised munitions investments.

Deadly Variance

Absent a sustained increase in spending for munitions and mines, industrial bases are left without a clear demand signal. They see variance rather than upward consistency. Many of these highly unique and specialized contractors operate in a monopsony market — unless they are lucky enough to support a foreign military sales contract, their sole customer is the Pentagon.

Year-to-year variance from their sole customer makes it difficult to keep plants open at all, and it is near-impossible for private industry to proactively invest. As the war in Ukraine has shown, even when plants are fully cranking, it can take years to surge production.

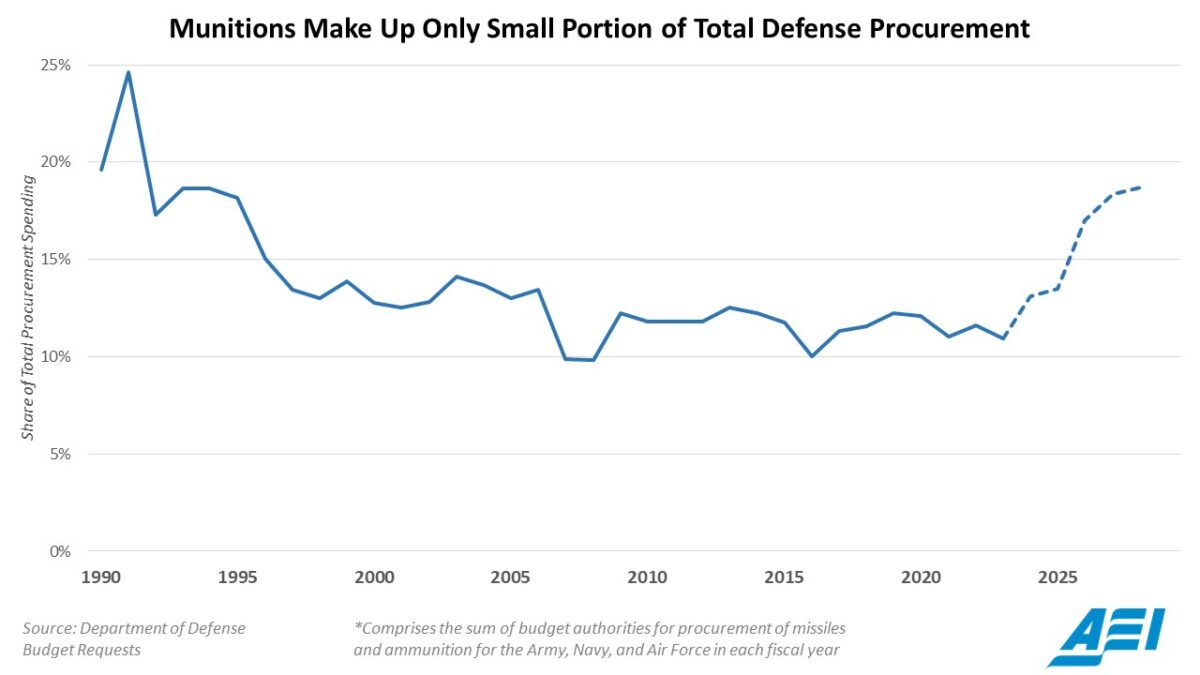

Receiving relatively few dollars from the shrunken procurement pot makes it hard for these companies to keep lines open. Just over 10 percent of procurement dollars today buy the payloads that make the weapons for our weapons systems. Without bullets, bombs, missiles, or rockets, our weapons systems are little more than very expensive paperweights.

It is crucial that Washington not only outfit the military with the weapons it needs immediately, but also build a resilient stockpile capable of lasting in a protracted war.

Munitions Win Wars

Take for example the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), an air-launched projectile that would be key to defeating enemy fleets in a potential conflict. In the president’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2024, the Pentagon procures only 118 of these missiles, split between the Navy and Air Force. In previous fiscal years, the quantities were even smaller.

In a conflict with sophisticated enemies, insufficient quantities of key munitions would quickly limit the U.S. military’s ability to win. A CSIS wargame estimated that in a potential conflict with China over Taiwan, the U.S. would deplete its stockpile of LRASMs within a week, a dreary reality check for our brittle industrial base.

Even when given the tools, namely funding and authorities, to fix this problem, not all parties use them fully. For instance, last year Congress provided authorities for the signing of multiyear procurement contracts to purchase a variety of munitions, and the Army and Air Force are smartly taking advantage.

Yet House appropriators won’t approve requests for the SM-6 and AMRAAM missiles, sending yet another wavering signal to industry about U.S. willingness to spend on missiles and munitions. Worse, House appropriators cut funding for Air Force missile procurement and Navy weapons procurement by over $1 billion for the coming fiscal year.

Congress cannot keep shorting munitions investments and expect anything but a brittle, fragile, slow-to-respond industrial base. Only clear and consistent demand and funding will change the trend. Congress should allow multiyear authority for these two missiles and use supplemental funding to add more funds to the missiles and munitions accounts that are not yet maxed out. Purposeful and sustained commitment to munitions production is crucial to revitalizing our ailing industrial base and fixing the munitions shortages.

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Mackenzie Eaglen is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she works on defense strategy, defense budgets, and military readiness. She is also a regular guest lecturer at universities, a member of the board of advisers of the Alexander Hamilton Society, and a member of the steering committee of the Leadership Council for Women in National Security.

No comments:

Post a Comment