Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project. In this edition of 2-2-2, SCSP Director for Foreign Policy Will Moreland reflects on the recent Kigali Global Dialogue and lessons for engaging those developing economies that are skeptical of, but essential actors in, the global technology competition.

Recognizing a competition is the first step in winning one. For too long, the current international competition grew with inadequate recognition. Then history began a sharp turn. Evidence of expanding authoritarian “tech spheres of influence” started to emerge. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine brought a stark reminder that authoritarian aggression persists. Within the United States, awareness of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a competitor now has grown. Internationally, Washington’s re-engagement with core partners — from NATO and the G7 to the Quad and beyond — has also yielded deeper alignment. Within that close circle, momentum appears strong.

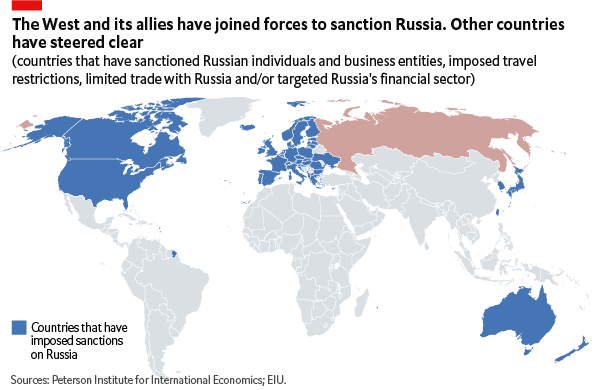

However, a wider lens reveals a more fraught picture. Beyond those allies and partners, skepticism of the competition paradigm is deepening, particularly for countries in the “Global South.” Many of these concerns are not new. For years, there has been a refrain of “don’t make us choose” between Washington and Beijing. Russia’s blatant territorial aggression spurred only tepid interest in sanctions outside the West. An entire recent Foreign Affairs issue heralded a new age of non-alignment and “fence sitters.”

The United States can ill afford to ignore the concerns of over two-thirds of the world’s population. Attending the recent Kigali Global Dialogue offered greater insight into these concerns. An American response demands a combination of a new positive vision for a tech-enabled future and specific steps to engage developing countries on their priorities.

SCSP Director for Foreign Policy Will Moreland speaks at the Kigali Global Dialogue

A Sea of Challenges

As SCSP’s recent travels in the Indo-Pacific illustrate, U.S. tech prowess still inspires worldwide respect. Nonetheless, countries have real concerns about how that U.S. tech edge will be put to use, how they can access and benefit from those tools, and their voice in shaping rules and norms around those technologies.

In Kigali, geopolitics was an unwelcome guest at a conference focused on the intersection of technology, development, and governance. Yet, it pervaded all three days. Whether discussing food security or the upcoming BRICS summit, geopolitical dynamics lurked behind every conversation. However, for many countries battling challenges around public health, economic development, and climate change, man-made geopolitical struggles can seem like optional problems thrust on them.

Impacts are particularly felt in areas like food security. As Shoba Suri of the Observer Research Foundation (a Kigali Dialogue host) has outlined:

“Around 80 percent of the world’s population lives in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, where farming households are disproportionately poor and vulnerable. These regions are particularly at risk of crop failures and famine brought on by climate change.”

Nor are these negative impacts narrowly limited. Disruption begets further disruption. For instance, food inflation reaching 24.61 percent remains a key driver of broader inflation roiling the Nigerian economy. Catastrophic geopolitical events like the Russia-Ukraine War, which is disrupting global food supply chains, are as likely seen as unnecessary compounding factors to existing challenges as problems in their own right.

Loading of a Ukraine Grain Shipment in 2021. Source: Shutterstock.

Likewise, the Global North’s focus on geopolitics raises concerns as to whether advanced industrial democracies are reliable partners genuinely invested in the priorities of Global South nations. Some in developing countries are quite skeptical of leveraging the U.S.-PRC competition to obtain funding or technical assistance to support local objectives. The Cold War’s shadow looms large. No country wants its development agenda instrumentalized as a geopolitical pawn.

Being caught in a development tug-of-war can chill capital-intensive projects. Developing economies fear shifting geopolitical winds will cause investors to withdraw from local projects. And, most basically given the scale of the developmental, green financing, and public health investments required, some chafe at choosing between U.S. or PRC funds when neither pot of money alone meets the overall need.

Even unintentionally, Global North policies adopted for geopolitical rationales can have collateral effects on Global South nations that speak to a lack of caring. As one speaker noted, moves like the Inflation Reduction Act are not heralded as a bold step on the shared global challenge of climate change, but as a “protectionist race to the bottom.”

Simultaneously, that skepticism bleeds over in some cases to Western tech companies. Multiple factors underlie this suspicion. Again, the geopolitical factor raises its head. Fears of vulnerability drive some to emphasize building autonomous local tech capacities. The lessons of decades of U.S. sanctions and the Ukraine War are that the West can sever access to these services at a whim. Regardless of whether a direct and intentional policy choice or “acceptable” collateral damages in pursuit of other objectives, the resulting damage is done.

International Sanctions on Russia Following the Invasion of Ukraine (April 2022). Source: Economist Intelligence Unit.

At the same time, the legacy of colonial exploitation cannot be ignored as a factor at play. Particularly when it comes to Western tech companies’ data collection, extractive parallels are quickly drawn. When compared to affordable and accessible alternatives like India’s Digital Public Infrastructure push, Western tech platforms can be depicted (regardless of the fairness of the characterization) as rent seekers.

Fundamentally, these preceding concerns speak to the Global South countries’ lack of voice in international governance and rule-setting, which limits their ability to protect and advance their interests on the global stage. That lack of voice dampens the outrage regarding recent geopolitical crises that these nations may express compared to that felt by the industrialized democracies. As one South African speaker reminded the audience, the old multilateral ideal never truly existed for Africa in the same way it did for Europe and the United States. Instead of the general peace and prosperity ascribed to the rules-based international order in the West, the order has been described as “increasingly frayed and unresponsive to the needs of developing countries.”

That same drive to expand the developing world’s representation at the “high tables of global governance” also complicates the values-based alignment the United States and its like-minded partners seek to build. While the United States speaks of a battle between democracy and autocracy, more seats at the table can take priority over the regime type sitting at it. Today’s focus for many is first and foremost achieving Global South representation in the halls of power, such as an African Union seat at the G20. For the moment, at least, the democratic character of those voices matters less.

India prepares to host the 2023 G20 Leaders Summit. Source: Shutterstock.

Preparing for a World of Multialignment

The preceding points of tension with the United States and its allies do not presage a major swing toward the PRC. Fortunately for the United States, some in Global South countries also see the PRC as a problematic partner. The PRC’s Digital Silk Road may provide the technology, funding, and resources that many nations desire. However, there is a deepening recognition of the surveillance and security costs that come with those investments. Likewise, the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative has created points of friction as tightening economic conditions have increased pressure on many Global South countries vis-a-vis PRC debt. The debt distress confronting many developing countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, is quite urgent. As the PRC continues to increase its use of coercive economic tactics, the space will only grow for conflicts to emerge.

Given these overlapping points of friction, U.S. policymakers should anticipate a future of multi-alignment rather than predicted non-alignment. Developing nations will look to partner and adopt stances issue by issue instead of embracing ideologically-centered positions. Perhaps nowhere is this approach more evident today than India’s simultaneous membership in the Quad and BRICS, straddling geopolitical divides. In a world with a plethora of cross-cutting challenges, other developing countries are likely to adopt similar strategies to maximize their leverage on specific issues. Each issue — and what a partner can offer in addressing it — will matter in its own distinct right.

Meeting the Moment: A Glass Half Full

Fortunately, the United States is already on the march to adapt to this evolving international landscape. Many of the puzzle pieces are present. Policymakers now must put them together. To begin, the United States recognizes and has reembraced the importance of transnational challenges. Like its predecessor, the 2022 National Security Strategy (NSS) emphasizes the core geopolitical challenges confronting the United States. But the 2022 NSS also highlights the importance of international cooperation on shared challenges — even at times with rivals.

The 2022 NSS, and subsequent statements, appreciates that transnational challenges ranging from climate change to public health and food security are concerns both for the United States in their own right and for other nations with whom the United States must partner to advance its interests. Thus, it is in the U.S. national security interest to recognize and work on those transnational issues both inherently and instrumentally. Recently, the Biden Administration has reinforced statements affirming developing nations’ priorities with tangible action. The December 2022 U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit yielded an estimated $5.7 billion in new two-way trade and investment.

Simultaneously, the same issues that animate many Global South actors inspire innovators in the U.S. private sector. Combating climate change is an ever-more vibrant startup space. Established American tech firms and incubators are backing start-ups providing new solutions for developing world challenges. U.S. venture capital is increasingly interested in betting on local, home-grown Global South startups.

Now it is the U.S. Government’s obligation to combine its recognition of these challenges with America’s private sector capabilities. The United States must promulgate a vision that both speaks to the world and mobilizes the U.S. private sector. A new vision must outline not only the world to be avoided — one ravaged by conflict, techno-authoritarian dominance, or poverty, famine, and disease — but what a positive tech-enabled future looks like. The United States must lay out a program for harnessing emerging technologies to improve individuals' daily lives, opportunities, and governance at home and around the globe.

It is understandable that the U.S. Government is just beginning to lay out such a vision in detail. National narratives are like supertankers. Ships do not turn on a dime. For the past seven years, the U.S. Government has worked to turn the ship’s wheel, explaining both at home and abroad why the preceding decades’ strategies are not adequate for today’s environment. That convincing required significant work and continues today.

Nonetheless, that first phase of redefining American strategy for the 21st century has come to an end. The more challenging and complicated work of the second phase — building out that positive vision — must begin today.

Three Steps Forward

As American leaders and policymakers begin to chart that course, the Kigali Dialogue offers three principles to keep in mind vis-a-vis the developing world.

First, to build a new vision, the United States should seek to center voices from Global South nations. A key critique of the leading 20th-century institutions is their divided nature, excluding much of the world in decision-making. A vision for a tech-enabled 21st-century international order must incorporate developing world voices alongside industrial democracies. UN Security Council reform is a long-running issue. However, the Biden Administration already has indicated its support here, and any move to expand its representation would be a strong initial measure to ensure the right players are at the right tables to address the world's future challenges.

UN Security Council Chambers. Source: Shutterstock.

Second, as U.S. policymakers work to craft the new institutions and rules of the road underlying a forward-looking vision, they should center technology concerns found in Global South nations. Emerging tech presents a range of opportunities but also particular challenges and, therefore, priorities for Global South countries. For instance, developing nations have specific concerns surrounding the impact of generative AI and other technologies that impact labor. When economic opportunity is a stability imperative, such questions become core security issues in a way they may not in the advanced industrial world. Looking ahead, it is critical to have Global South voices at the table not only for the resulting conversations on governance, but the initial conversations shaping the table as to what, where, when, and how to govern.

Third, American policymakers must center the expertise of Global South actors to learn from their experiences. Technology may be global, but the best solutions are often context-dependent. As the private sector has learned, what works in one market may not in another. U.S. leaders building new institutions should aim to learn from the Global South experts as much as offer solutions based on Global North conditions. Such an approach would recapture previous experiences of the Good Neighbor policy and the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions, where U.S. experts engaging in technical assistance programs gained new ideas and insights from the host countries as much as they offered guidance. In this vein, the United States could gain an easy win by supporting South-South collaboration on innovation and governance. Practically, solutions from one developing country may best align with conditions on the ground in another. Normatively, there is a powerful desire to end perceived dependencies that accompany all roads running through the Global North. In a time where resilience is the growing watchword, the United States should support lattice works of engagement options, not options deploying a hub and spoke model.

No comments:

Post a Comment