Zhou Xin in Hong Kong Coco Feng in Beijingand Minghe Hu in Beijing

The Chinese government has made technology and innovation key priorities in its development plans for the next five years, as it strives to build a “Digital China” and overtake the US as the world’s No 1 economy. In this third and final part of a series looking at the politicisation of China’s internet landscape, we explain how the views of China’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, about the internet have evolved into what they are today.

In August 2013, after just five months as China’s top leader, President Xi Jinping held a closed-door meeting with the country’s propaganda officials in Beijing to raise concerns about the Communist Party losing control of the national narrative online.

“The internet is now a key battleground for public opinion,” Xi said in a speech at the time. “Anti-China forces in the West have always tried to ‘topple China’ via the internet … Whether we can hold on and win the fight on the battlefield of the internet matters to our ideological security and regime safety.”

New insight into Xi’s thinking on the role of the internet and its relationship to state power were unveiled with the publication of a new book titled Excerpts of Xi Jinping’s Discourse on Cyberspace Superpower, which contains selections from remarks he gave between early 2013 and the end of 2020. Some of these had been a state secret until the book went on sale in January.

The 171-page book groups Xi’s quotations into nine chapters under themes such as “enhancing the party’s centralised leadership over cyberspace affairs”, “making China a cyberspace superpower”, “winning the battle of online ideological struggle”, and “building up shared destiny in cyberspace”.

The book offers a glimpse at how the Chinese leader’s views of the internet evolved, from taking a defensive strategy that regarded the internet as a potential risk to using it as a tool for amplifying and expanding China’s influence and power. One Chinese government official, who declined to be named, said the fact that the speeches are being published now showcases Beijing’s fresh confidence in its approach to internet governance. This confidence has been further bolstered by the fractious politics of the US, exacerbated by a more freewheeling online environment, which helped give rise to conditions leading to the attacks on the US Capitol building in January.

These views have shaped the development of the internet in the world’s most populous country in recent years, leading to a model of governance that has been criticised abroad as a form of “digital authoritarianism”. At the same time, internet development in China has unleashed new sources of economic growth, raising living standards and helping turn China from a technological copycat into an innovator and, in some market segments, a leader.

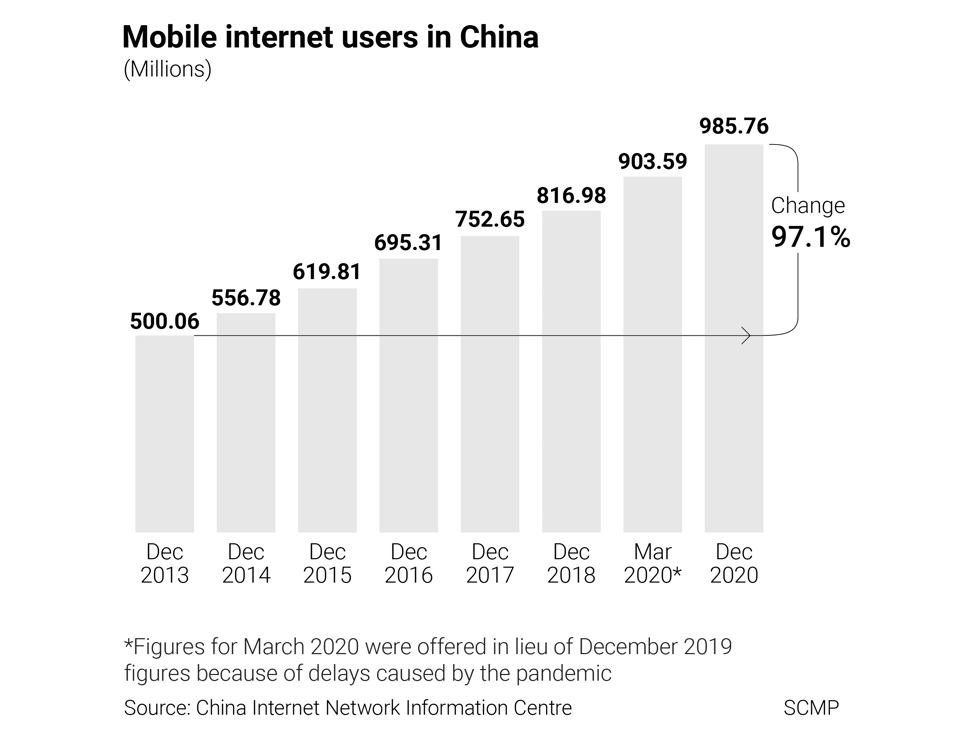

Since Xi came to power, China’s biggest internet firms have grown to equal the likes of Amazon, Facebook and Google. The number of internet users also ballooned during this period to nearly 1 billion, with online retail sales growing from 1.3 billion yuan (US$200 million) in 2012 to 9.8 trillion yuan in 2020. In recent years, the country has also been investing heavily in cutting-edge technologies, and Xi has increasingly discussed applying technologies such as artificial intelligence and blockchain to improve national development and governance.

In 2013, though, China’s internet industry was still weak. Google’s pull-out in 2010 made the country looked isolated. China’s technology industry was inferior to that of the US in both hardware and software. More importantly, the Chinese governing apparatus was largely untrained in managing the internet, a decade after the country’s Great Firewall went into effect. It was also more common at that time for people to use the internet to promote free speech and a pluralistic society. Opinion leaders such as Ren Zhiqiang, who was sentenced in 2020 to 18 years in prison on corruption charges, openly challenged official narratives coming from Beijing.

This is why Xi, who became the Communist Party’s general secretary in late 2012 and the country’s president the following March, viewed the internet at that time as a source of concern, where authorities were on the defence.

Xi determined that the government needed to take more initiative in shaping ideology online, according to his speeches. In his 2013 speech, Xi said China’s official propaganda outlets must avoid “being marginalised” on the internet, and he urged the national propaganda apparatus to acquire the skills necessary to “carry out online public opinion struggles”.

“It is not an easy job, but we have to do it no matter how hard it is,” Xi said. “Fewer negative comments online can only do good to our social development, social stability and the happy living of our people.”

Ryan Fedasiuk, a research analyst at Georgetown University’s Centre for Security and Emerging Technology, noted that the early days of Xi’s tenure marked “a drastic shift” in managing online content from the policies of the preceding decade under then-president Hu Jintao.

“The Party launched a crackdown on internet rumours and established the ‘seven baselines’ [in censoring online discussions],” Fedasiuk said. The seven baselines, also known as the “seven things not to talk about”, included topics such as universal values, freedom of the press and civil rights.

John Lee, a senior analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, said Xi’s concerns about the internet were also partly informed by geopolitical events overseas.

“Apparent catalysts were Edward Snowden’s revelations about the extent of China’s vulnerabilities in cyberspace and the ‘Arab spring’ political revolutions, combined with the Obama administration’s commitment to supporting ‘internet freedom’ as a US foreign policy principle, which highlighted the internet’s potential to subvert the Communist Party’s narrative control,” Lee said.

Documents leaked by former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Snowden in the summer of 2013 revealed for the first time the broad extent to which the US was monitoring cyberspace and unveiled the tools it used to do it. The leaks detailed the NSA’s collection of telephone records and how it requested user data from large internet firms, including Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Yahoo, to track online communications in a programme known as Prism.

For Xi, the leaks confirmed concerns about US surveillance, spurring Beijing to cut the use of foreign equipment and software in key systems. In his 2013 speech, Xi cited Prism and XKeyscore, another US computer system unveiled by the Snowden leaks that collected and analysed global internet data, as evidence for why China must stay alert to external cyber threats.

In the intervening years, Xi has repeatedly reasserted his views on the internet as an ideological battleground, urging government cadres to be alert to the threat.

As late as 2018, Xi had asked internet police to look deeper into “who is starting rumours, what motives do they have, and whether there are hostile forces hiding behind” them. But that same year, Xi started to emphasise the internet’s role in easing the country’s rise and the Communist Party’s rule.

China's President Xi Jinping is seen on a screen before the opening ceremony of the World Internet Conference (WIC) in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province, on November 23, 2020. Photo: Reuters

“We have fundamentally changed the situation in the past when chaos was rampant, our positions were lost, and we were always on the defensive side [on the internet],” he said.

Xi asked the country’s officials to emphasise the good the internet can do for the country and take advantage of it as a powerful governing tool in a “new [global] competition of comprehensive state power”. He called it a “once-in-a-thousand-year opportunity for the Chinese nation” to thrive.

“To some extent, the countries that take command of the internet will win the world,” Xi said.

In 2017, Xi said China could use big data to “modernise state governance”. The following year, he elaborated that this was because the internet enabled the government to get its hands on “all data” instead of relying on smaller samples.

With the maturation of China’s internet economy, tech giants such as Tencent Holdings and Alibaba Group Holding, the owner of the South China Morning Post, have grown in size and clout, and Xi started to see them as requiring state guidance.

In his 2018 speech, Xi said that China needs more internationally competitive internet firms while ensuring their growth does not threaten national security.

China now has nearly 1 billion internet users

“We cannot sacrifice security for development and we cannot let [internet] enterprises become wild horses without reins,” Xi said.

The Chinese government’s rising confidence is also reflected in its efforts to shape opinions outside the country.

In recent years, Chinese state media and diplomats have increased their presence on overseas platforms such as Twitter to engage in sometimes heated exchanges on topics related to China. Georgetown University’s Fedasiuk said China is now trying to influence public opinion overseas as Beijing pays more attention to how the rest of the world views China after silencing domestic critics.

But China’s assertion that the internet should serve the state is still “at odds with global norms around internet freedom and the free flow of information”, Fedasiuk said.

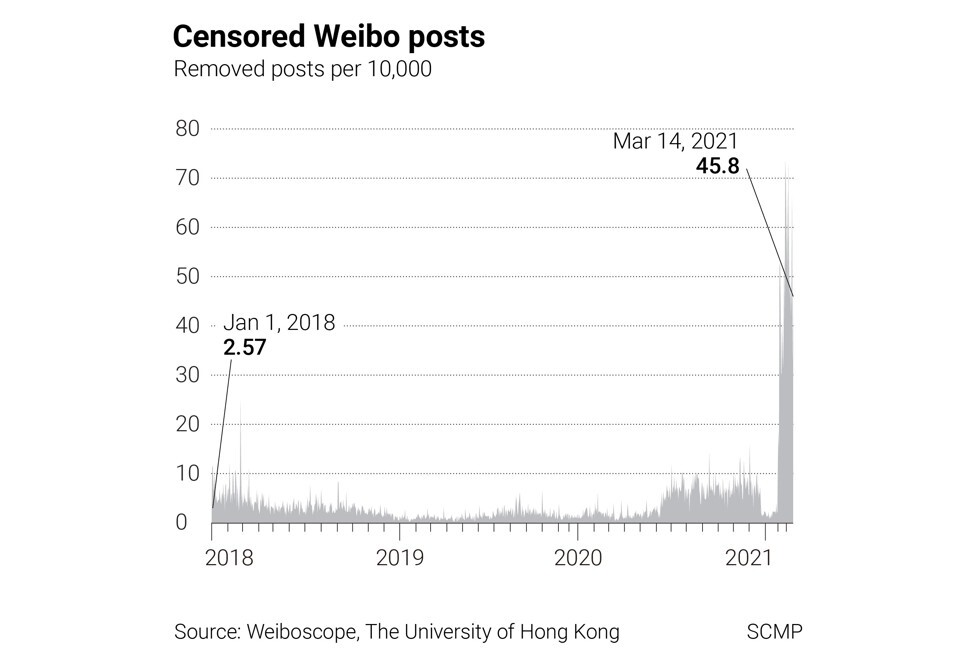

Debate about the merits of China’s internet policies has not ended. Beijing has been criticised over censorship of early warnings of the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, possibly one reason the virus spread out of control.

Beijing has pushed back, saying China’s use of new technologies for social tracking helped it contain the pandemic. Xi said in November that “the internet has played an important role in economic recovery, social functioning and international cooperation”.

People wearing face masks to protect against the spread of the coronavirus use their smartphones as they walk through Ditan Park in Beijing, Tuesday, Feb. 9, 2021. Photo: AP

Over the last few years, however, dissident voices have not been Xi’s primary concern regarding cyberspace. A bigger worry has been cybersecurity challenges and China’s reliance on Western countries for certain technologies. Under former president Donald Trump, the US escalated a technology war by restricting Chinese companies’ access to US technologies.

This is why Xi has made technological self-sufficiency a key policy for China, and it is something he has called for repeatedly in his speeches over the years.

“Key internet technologies are our biggest lethal weakness, and the reliance on others for core technologies is our biggest danger,” Xi said in 2016, 2018 and 2019.

In the 2018 speech, he added, “Without core technologies, our efforts of building up a cyberspace superpower will be … like building a castle on the sand, as it cannot withstand any wind or rain.”

No comments:

Post a Comment