Richard Engel, Charlotte Gardiner, Jennifer Jett and Alexander Smith

HSINCHU, Taiwan — A military conflict over Taiwan would set the global economy back decades because of the crippling disruption to the supply chain of crucial semiconductors, according to the head of one of the island’s leading makers of microchips.

Taiwan, a self-ruling democracy about 100 miles off China, makes the world’s most advanced microchips — the brains inside every piece of technology from smartphones and modern cars to artificial intelligence and fighter jets.

China claims Taiwan as its territory and has said it would be prepared to use force to take control of the island, although it has not laid out any timeline for doing so. Officially, the U.S. discourages conflict but takes a neutral stance, although President Joe Biden has repeatedly suggested he would step in to defend Taiwan.

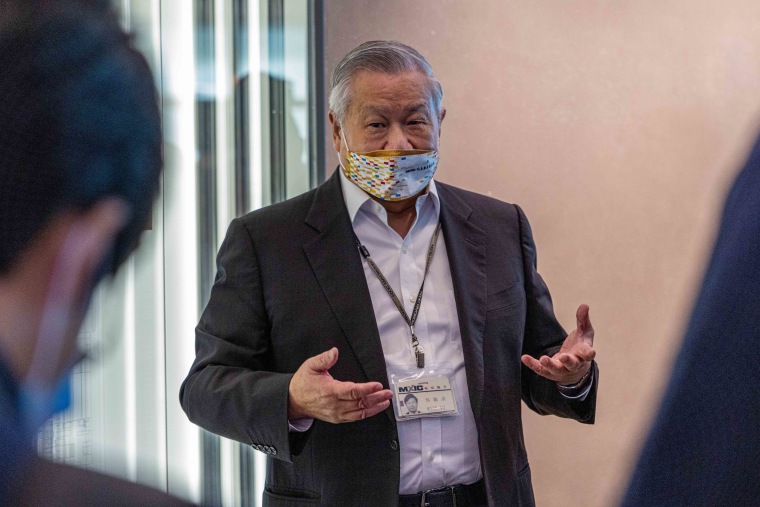

If the industry were to be disrupted by military conflict, the impact on the global economy would be “huge,” said Miin Wu, the founder and chief executive of the Taiwanese chipmaker Macronix.

“My opinion is, you will be set back at least 20 years,” he told NBC News on Monday in the company’s showroom at Hsinchu Science Park in northwestern Taiwan.

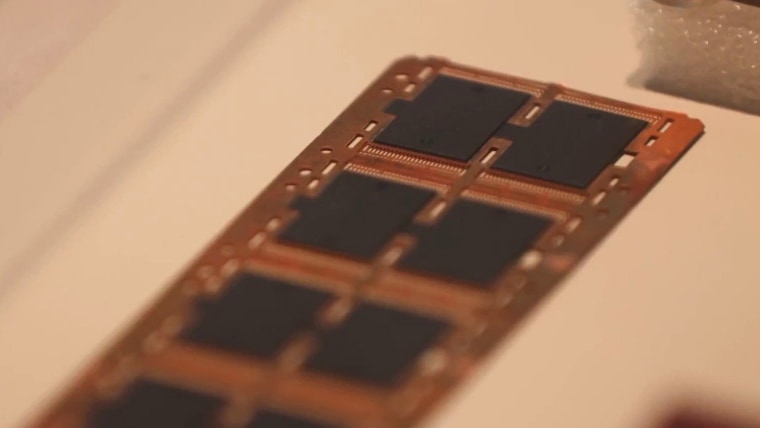

The island is a microchip fabrication hotbed, producing 60% of the world’s semiconductors — and around 93% of the most advanced ones, according to a 2021 report from the Boston Consulting Group. The U.S., South Korea and China also produce semiconductors, but Taiwan dominates the market, which was worth almost $600 billion last year.

These technological wonders consist of tiny patterns, measured in nanometers, that are etched onto thin slices of silicon called “wafers.”

Wu, 75, played a major part in establishing Taiwan’s chip industry when he founded his company in 1989, having spent more than a decade working in Silicon Valley, including as senior manager at Intel. He brought some 40 senior Taiwanese engineers back with him.

If Taiwan’s semiconductor industry were disrupted by military conflict, it would set the global economy back at least 20 years, according to Miin Wu, founder of the Taiwanese chipmaker Macronix.Annabelle Chih / Getty Images file

If Taiwan’s semiconductor industry were disrupted by military conflict, it would set the global economy back at least 20 years, according to Miin Wu, founder of the Taiwanese chipmaker Macronix.Annabelle Chih / Getty Images fileThe Macronix campus has a Silicon Valley vibe, with employees bouncing between work and an on-site gymnasium, a roller-blading area and a large park. Displays in the company’s showroom explain how the chips are made and showcase products in which they are used, from Fitbits and Nintendo game consoles to cars and medical equipment.

“I thought the only thing I want to do is I want to develop technology based on the U.S. standard and then move up,” Wu said.

He said he never anticipated that semiconductors would become one of the most important industries in the world — and one that is now at the heart of spiraling tensions between the U.S. and China, the planet’s two biggest economies.

Relations between the two countries have been at a low ebb in recent years as disputes have arisen over a range of issues including trade, human rights and Russia’s war in Ukraine, as well as Taiwan, whose government the U.S. doesn’t recognize officially but is bound by law to supply with defensive weapons.

Taiwan’s semiconductor industry has been described as a “silicon shield” that gives the U.S. and other supporters added incentive to promote the island’s security in the face of growing threats from China.

Since the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949 after a civil war, its ruling Communist Party has claimed sovereignty over the island, where the defeated Nationalist forces set up a rival government.

Like his predecessors, Chinese President Xi Jinping says China desires “peaceful unification” with Taiwan but has not ruled out the use of force.

The U.S. has a long-standing policy of “strategic ambiguity” in terms of how it would respond if China attacked Taiwan, the idea being to deter Beijing from invading and discourage Taipei from doing something — like declaring independence — that might provoke a military response from its neighbor.

Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, Calif., in April.Eric Thayer / Bloomberg via Getty Images file

Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, Calif., in April.Eric Thayer / Bloomberg via Getty Images fileAny instability in the Taiwan Strait “resulting from escalation, accident or use of force would have major economic and security implications for the region and globally,” according to a State Department readout of a call last week between Undersecretary of State Victoria Nuland and her European Union counterpart, Stefano Sannino.

Biden, however, has appeared to move away from strategic ambiguity by saying on several occasions that Washington would step in to defend Taiwan. Each time, the White House later said that U.S. policy on the island had not changed.

Though Taiwan may be small, Malcolm Penn, chief executive of the British semiconductor industry consultant Future Horizons, agrees with Wu that a war over the island would “bring the world to its knees” because of the disruption to global chip supply.

“It would make Covid seem like a walk in the park,” he said, “and it would hurt China just as much as anyone else.”

Robert Tsao, a Taiwanese billionaire who made his fortune in semiconductors, agreed that a war would “ruin everything” and be “disastrous for the international interests” of the U.S. and the world.

As part of its territorial claims, China also says it owns most of the South China Sea, a vital shipping route abundant with natural resources. This claim isn’t recognized in international law, and Washington’s attempts to demonstrate this by sailing ships and flying aircraft through the region have been met by Chinese vessels and planes “buzzing” their unwelcome backyard guests.

A Chinese soldier during combat exercises in the waters around Taiwan in August.Xinhua News Agency / via Getty Images file

A Chinese soldier during combat exercises in the waters around Taiwan in August.Xinhua News Agency / via Getty Images fileIt is against this backdrop that the Biden administration says it wants to “de-risk” its relationship with China — keeping trade essentially open but restricting certain areas that Washington believes could give China the upper hand when it comes to national security or future-defining technology.

Last year, Biden imposed a sweeping set of export controls designed to block China’s access to certain kinds of semiconductor chips made with U.S. technology.

These export controls and other technology restrictions have had implications for companies all over the world and Macronix is no exception. Like other Taiwanese chipmakers, it is barred from selling advanced chips to China, the island’s largest trading partner.

China has criticized the export controls as an abuse of trade measures that is meant to protect U.S. “technological hegemony.” Many industry figures agree Washington’s attempt to control the market is counterproductive.

The U.S. export controls will “delay but not stop China” from achieving technological parity, said Penn at Future Horizons.

“It may take 10 years, but they’ll do it: They have the resources to do it, they have got the scientific know-how, they have got the money, they have got the market, and now they’ve got the need,” he said.

Penn is among the experts deeply critical of Washington's export controls, calling them counterproductive. And this week the chief financial officer of American tech firm Nvidia, Colette Kress, said at an investor conference that introducing new restrictions would result in a "permanent loss of opportunities for the U.S. industry to compete and lead in one of the world’s largest markets."

The U.S., which produces about 10% of the world’s semiconductor chips and none of the most advanced ones, is also trying to boost domestic manufacturing, offering tax incentives for projects like the $40 billion factory being built in Arizona by the Taiwanese chip giant TSMC.

But building such a complex industry will take time, Wu said. “I would say 10 years,” he added.

Ultimately, he said, the stability of the semiconductor industry — and people’s access to the devices powered by it — depends on the leaders of China, Taiwan and the U.S.

“They have to make the right decision with their wisdom,” Wu said. “That is the solution.”

Richard Engel and Charlotte Gardiner reported from Hsinchu, Taiwan, Jennifer Jett reported from Hong Kong, and Alexander Smith reported from London.

No comments:

Post a Comment