JOSEPH CONNOR

By February 1942, the 74 men of Station Cast on the Philippine island of Corregidor had become some of the most important sailors in the U.S. Navy. These radio operators, linguists, and cryptanalysts were eavesdropping on enemy radio transmissions and had made steady progress deciphering the Japanese naval code. The U.S. military hoped this top-secret project would soon give the United States advance notice of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s plans.

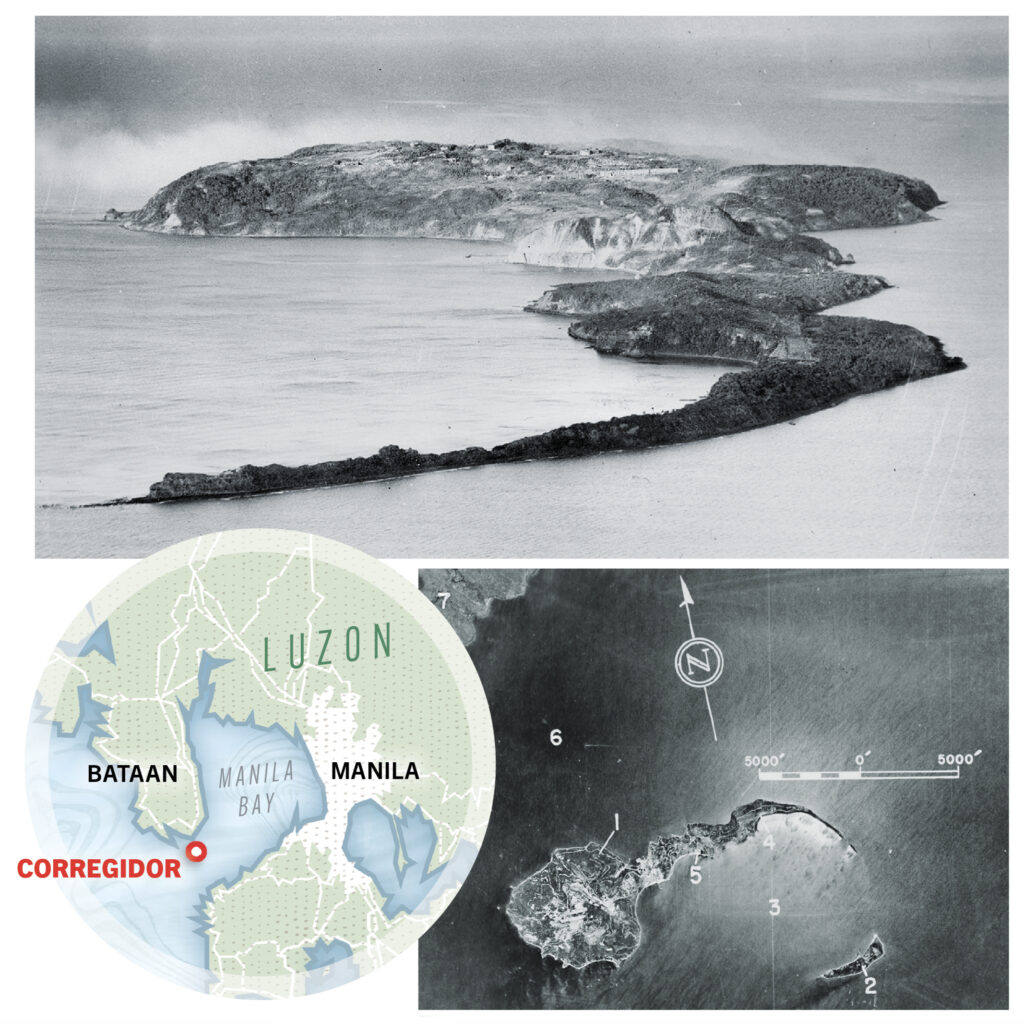

Station Cast’s problem was its location. The Japanese had invaded the Philippines two months earlier and were pushing the American and Filipino defenders back toward a last-ditch stand on the Bataan peninsula on the island of Luzon. Corregidor, a small fortified island in Manila Bay, lay only two miles off Bataan. If Bataan fell, which seemed inevitable, Corregidor would soon follow.

The navy couldn’t let Station Cast’s personnel fall into enemy hands. The Japanese knew what these men were doing and would torture them to learn American codebreaking secrets. If that happened, the enemy would change its codes, and that would force the navy to start the tedious, time-consuming process of figuring out the enemy ciphers from the beginning.

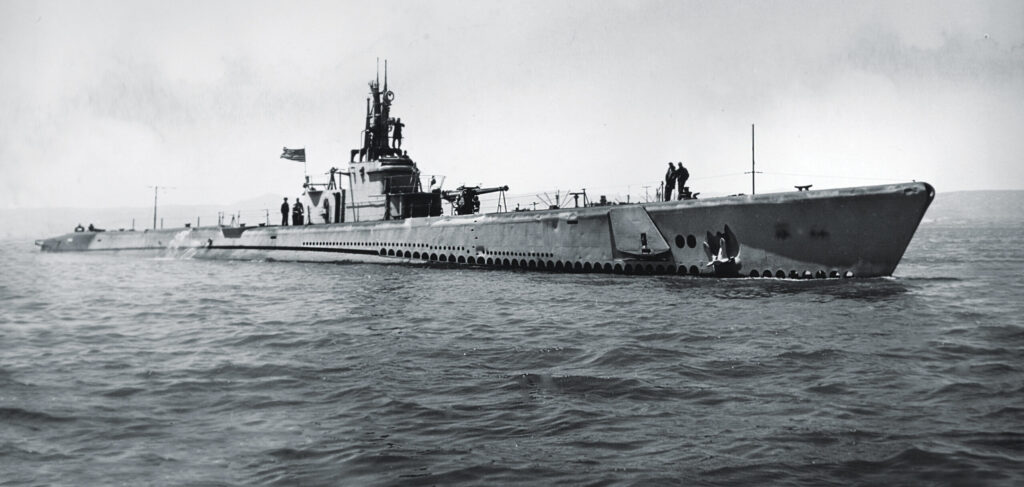

Evacuating the sailors posed monumental challenges. The Japanese had clamped a tight naval and air blockade on Bataan and Corregidor, making rescue by airplane or surface ship next to impossible. Submarines offered the only alternative, but they would have to dodge Japanese destroyers on the lookout for them.

Corregidor was a fortified island at the mouth of Manila Bay just offshore from the Bataan peninsula. Once Bataan fell, the capture of Corregidor was only a matter of time. (Top: National Archives; center: Hum Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images; map by Brian Walker)

Corregidor was a fortified island at the mouth of Manila Bay just offshore from the Bataan peninsula. Once Bataan fell, the capture of Corregidor was only a matter of time. (Top: National Archives; center: Hum Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images; map by Brian Walker)The men of Station Cast knew this and the knowledge gnawed at them. They wondered if the navy could rescue them and worried that their superiors had something far more drastic and final in mind. They feared that, one way or another, they wouldn’t get out of

Corregidor alive.

By the time the United States entered the war in December 1941, the U.S. Navy had made codebreaking a high priority. The Japanese relied heavily on radio signals to send information to their bases and warships across the Pacific, and their communication system was modern and efficient. The Japanese wrapped their messages in a dense code they believed to be unbreakable, but the U.S. Navy thought otherwise.

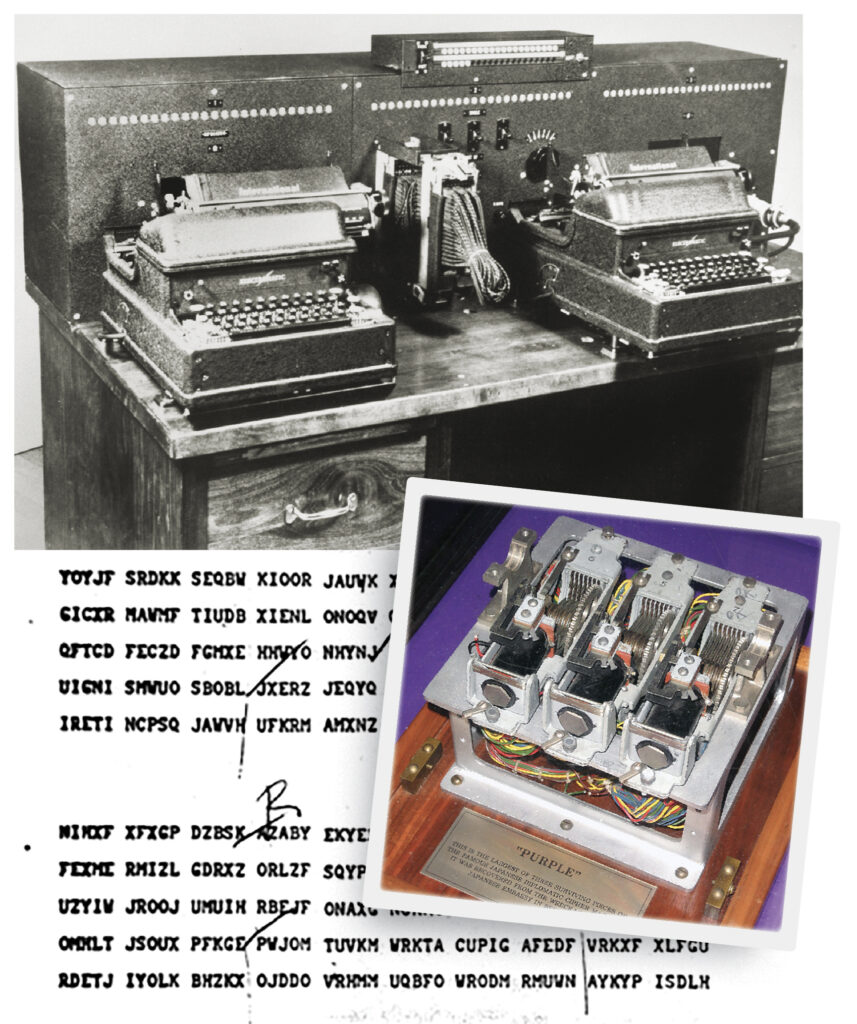

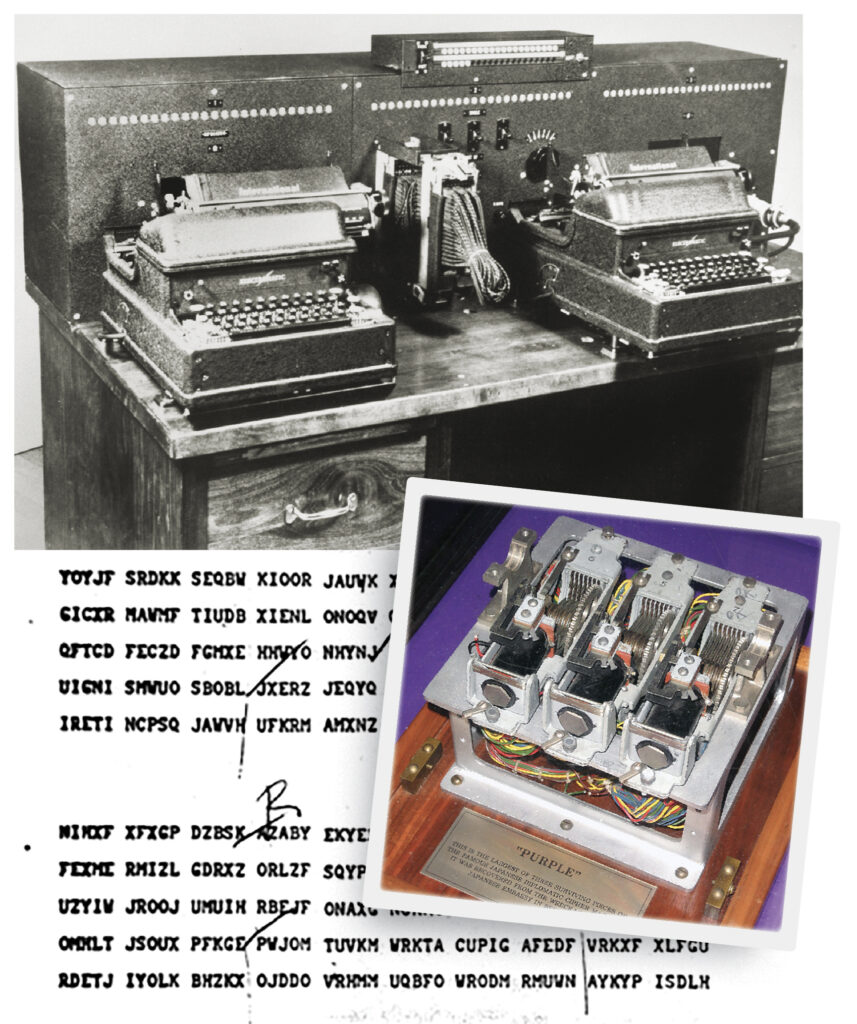

The American codebreakers were making significant strides. They had figured out the Japanese diplomatic code, which they nicknamed Purple, and the U.S. government could now read the top-secret dispatches Tokyo sent to its embassies. The juicier prize was the Japanese Navy’s operational code, dubbed JN-25. This code, adopted in 1939 and in use since 1940, was complex and sophisticated. It used about 45,000 five-digit combinations, each representing a different word or phrase. Random numbers, known only to the sender and recipient, were added to complicate things even further.

Still, the navy codebreakers were making headway. In December 1941, for example, Station Cast scored a breakthrough when it intercepted a message mistakenly sent in both code and plain text. By comparing the two, analysts began to better understand how JN-25 worked. Nevertheless, progress was slow: just a word here and a phrase there, but each deciphered word or phrase became a building block for further discoveries.

The headquarters of the navy codebreaking operation was Station Hypo in Hawaii. Station Cast served as an advance outpost and operated from the Navy Intercept Tunnel in an area of Corregidor called Monkey Point, located on the tail of the three-mile-long, tadpole-shaped island. More than 10,000 American and Filipino soldiers, sailors, and Marines were stationed on Corregidor, and General Douglas MacArthur directed the defense of the Philippines from his headquarters there.

Corregidor offered an ideal spot for interception work because radio reception there was remarkably clear. It was also, pre-war navy planners believed, “well protected and can be held for several months after the outbreak of war.”

Top: American codebreakers put together a machine that helped them crack the Japanese “Purple” diplomatic code. Bottom right: This piece of a Purple machine was taken from the Japanese embassy in Berlin at the end of the war. Bottom left: Encrypted Purple messages looked like random letters. The handwritten notations were to indicate how to adjust the machine’s rotors to break the code. (Top: Granger; inset: National Cryptological Museum; background: National Archives)

The Navy Intercept Tunnel had been built before the war, ironically with cement imported from Japan. It was 12 feet wide and 220 feet long, with two lateral tunnels branching off to the sides. It was stocked with high-tech equipment that included 11 National model RAO shortwave radio receivers, 21 specially built Underwood typewriters to translate Morse code into the Japanese alphabet, various IBM machines that were precursors of modern computers, and direction-finding equipment to determine the origin of enemy radio transmissions. It also housed a so-called Purple machine, which decrypted Japanese diplomatic messages and was one of the fewer than a dozen such machines in existence.

Station Cast was a hush-hush operation, and security was tight. A double iron gate blocked the tunnel’s entrance. Classified documents were stored in a vault protected by a triple-combination lock, and a Marine sentry stood guard at the tunnel entrance 24 hours a day. To disguise the outfit’s true purpose, it was called the Emergency Radio Station, with a cover story that it was merely a back-up communications system for the U.S. Asiatic Fleet.

The station had two components: a general unit, which did the interception work, and a special unit, which analyzed the intercepted messages. The cryptanalysts were a special breed. Their work required a high IQ, an abundance of curiosity, and painstaking attention to detail. They were dedicated to their craft. “I have never seen a more devoted group of workers. Many of us often worked two shifts a day,” said Ensign Laurance L. MacKallor, one of the codebreakers. “The work was too challenging to put down as long as one could keep his eyes open.”

The tunnel protected the men from the frequent bombing raids, but the war hit home in other ways. Lieutenant Rudolph J. Fabian, a cryptanalyst, had stockpiled crates of food for Station Cast, but the army confiscated these rations and put them into the communal pot for the entire Corregidor garrison. After that, said Chief Yeoman John E. “Vince” Chamberlin, Station Cast’s personnel ate only two sparse meals a day, mostly spaghetti and soggy rice. The skimpy fare wasn’t enough for active men in a tropical climate, and all lost weight. In four months, for example, Chief Radioman Sidney A. Burnett dropped 53 pounds, and Chamberlin lost 40. Occasionally, the chow contained meat, and when it did, Radioman James B. Capron Jr. worried that Monkey Point had gotten its name for a reason.

Corregidor was a likely target for a Japanese landing, so all troops, regardless of specialty or assignment, trained to defend its beaches. This posed a problem for Station Cast, whose arsenal consisted of only two .45-caliber pistols and one .22-caliber rifle, but an enterprising chief petty officer found a sunken barge in shallow water nearby and salvaged several crates of .30-caliber Enfield rifles. The men cleaned these weapons and practiced infantry drills, calling themselves the Monkey Point Militia.  Admiral Ernest J. King didn’t want to take the codebreakers out too early and risk disrupting the operation, but he understood that it would be a disaster if they fell into enemy hands. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Admiral Ernest J. King didn’t want to take the codebreakers out too early and risk disrupting the operation, but he understood that it would be a disaster if they fell into enemy hands. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Admiral Ernest J. King didn’t want to take the codebreakers out too early and risk disrupting the operation, but he understood that it would be a disaster if they fell into enemy hands. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Admiral Ernest J. King didn’t want to take the codebreakers out too early and risk disrupting the operation, but he understood that it would be a disaster if they fell into enemy hands. (Naval History and Heritage Command)The Japanese blockade isolated Corregidor from the outside world, and the men were on their own. No mail could get through from home, so their only contact with the United States came when they tuned in KGEI, a shortwave radio station in San Francisco. The codebreakers knew that Corregidor was doomed and in January 1942 they began burning sensitive documents, including used carbon paper, and destroyed any equipment they didn’t need for daily operations.

The navy high command pondered Station Cast’s future. It realized it couldn’t let these men fall into Japanese hands. “Their loss would represent a severe setback to our Communication Intelligence activities,” the brass noted on January 23. It recommended evacuation, but that presented daunting problems. Dodging the Japanese blockade to get out of the Philippines would be risky, and the loss of these men would eliminate nearly half of the American codebreakers in the Pacific theater. A mass evacuation was out of the question because, even if it succeeded, it would put Station Cast out of business for weeks as the men traveled to Australia and set up shop there. At this critical juncture in the war the codebreaking activities were essential. “Communication Intelligence organization…is of such importance to successful prosecution of war in Far East that special effort should be made to preserve continuity,” insisted Admiral Ernest J. King, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Fleet and, beginning in March 1942, chief of naval operations.

King ordered the men to be taken out in stages so Station Cast could keep operating on Corregidor for as long as possible. He knew the Japanese would eventually capture the island, but he couldn’t predict how much longer Bataan or Corregidor could hold out. He believed a staged evacuation was worth the risk.

While the high command pondered its options, the codebreakers learned there was a far more drastic plan in play. One evening, Radioman Duane L. Whitlock saw two officers in the tunnel sitting at their desks and cleaning their .45-caliber pistols. He jokingly asked if they were expecting a visit from the Japanese that night, but they didn’t smile. “No, these are for you and the others,” one of them explained. “We have discussed it between us and have decided we will not let a single one of you fall into their hands. When the time comes, we are going to shoot every one of you, then shoot ourselves.” Whitlock knew the officers weren’t kidding around. The general feeling, Radioman Burnett said, was that if “any of us got off the place alive, it would be a miracle.”

The evacuations began on February 5, 1942, at 7:31 p.m., when the submarine USS Seadragon (SS-194) surfaced off the coast of Corregidor. It left 15 minutes later, carrying four officers and 13 en-listed men from Station Cast. The submarine took them to the Netherland East Indies (now Indonesia). From there, they went to Australia to begin setting up a new Station Cast. The evacuation happened unexpectedly and on short notice, leaving the 57 men left behind startled to find their 17 colleagues gone so quickly that they had to leave all their worldly goods behind. Their clothing went into a “lucky bag” for communal use, and Chief Machinist’s Mate J.W. “Pappy” Lowery received their cigarettes for rationing. Station Cast remained in business. The navy had made sure that enough linguists, cryptanalysts, and radiomen stayed behind to do the work.

By March, the Japanese continued to push the Allied defenders farther back on Bataan. The navy high command realized that Bataan and Corregidor could fall at any time. “Evacuate personnel of Radio Intelligence Unit soon as possible…. Take all steps possible to prevent loss of personnel of Radio Intelligence Unit,” Admiral King ordered on March 5.

The evacuation would take time. While they waited, the men continued their daily work, and on March 16 they made a discovery, seemingly routine at the time, that justified King’s insistence on keeping the station open. The cryptanalysts determined that “AF” was the coded designation that the Japanese used for the Pacific atoll of Midway, a vital U.S. base 1,100 miles northwest of Pearl Harbor. Station Cast relayed this information to Station Hypo in Hawaii.  General Douglas MacArthur (left) had his headquarters on Corregidor. He was able to escape to safety aboard John T. Bulkeley’s PT boat, an option that wasn’t available to the large contingent of Station Cast personnel. (National Archives)

General Douglas MacArthur (left) had his headquarters on Corregidor. He was able to escape to safety aboard John T. Bulkeley’s PT boat, an option that wasn’t available to the large contingent of Station Cast personnel. (National Archives)

General Douglas MacArthur (left) had his headquarters on Corregidor. He was able to escape to safety aboard John T. Bulkeley’s PT boat, an option that wasn’t available to the large contingent of Station Cast personnel. (National Archives)

General Douglas MacArthur (left) had his headquarters on Corregidor. He was able to escape to safety aboard John T. Bulkeley’s PT boat, an option that wasn’t available to the large contingent of Station Cast personnel. (National Archives)That same day, the submarine USS Permit (SS-178) docked off Corregidor. It had originally been sent to evacuate General MacArthur and his staff, but MacArthur had left by PT boat five days earlier, a method of escape deemed impractical for the much larger number of Station Cast personnel and their equipment. Instead, the Permit took on board four officers and 32 enlisted men from Station Cast, as well as other assorted evacuees. The Permit now carried 111 men, nearly double its normal complement. Its mission was to get the codebreakers safely to Australia, but the submarine received orders to make a detour to hunt Japanese warships. It was a puzzling directive, since the men from Station Cast would be lost if the Permit were sunk.

That almost happened the next day. At 8:10 p.m., skipper G. “Moon” Chapple spotted three enemy destroyers near Tayabas Bay, southeast of Corregidor. Within minutes he fired two torpedoes from a range of 2,000 yards. The torpedoes missed but attracted the destroyers’ undivided attention. At 8:22 p.m., the Permit dove and the enemy ships attacked, dropping 12 depth charges that rattled the submarine, shaking bunks loose from bulkheads and light bulbs from their sockets. The persistent destroyers continued to hunt for the Permit with depth charges. With 111 men aboard the submerged submarine, the air soon became foul. There wasn’t even enough oxygen to light a match, Radioman Whitlock said, and Chapple took emergency steps to prevent suffocation. The Permit finally surfaced at 6:55 p.m. on March 18 after having been submerged for a harrowing 22 hours and 33 minutes. Ensign MacKallor called the episode “the most terrifying experience that I have ever undergone.” The Permit reached Australia on April 7.

Now only 21 men, including station commander Lieutenant John M. “Honest John” Lietwiler, remained behind to run Station Cast. They continued their interception and decryption work, usually toiling for 16-18 hours a day, but they knew that time was running out.

Of special concern was the Purple machine used to read diplomatic messages and the specialized IBM equipment used for decryption. The navy didn’t want these items to be captured because they might tip the Japanese off to American codebreaking secrets.

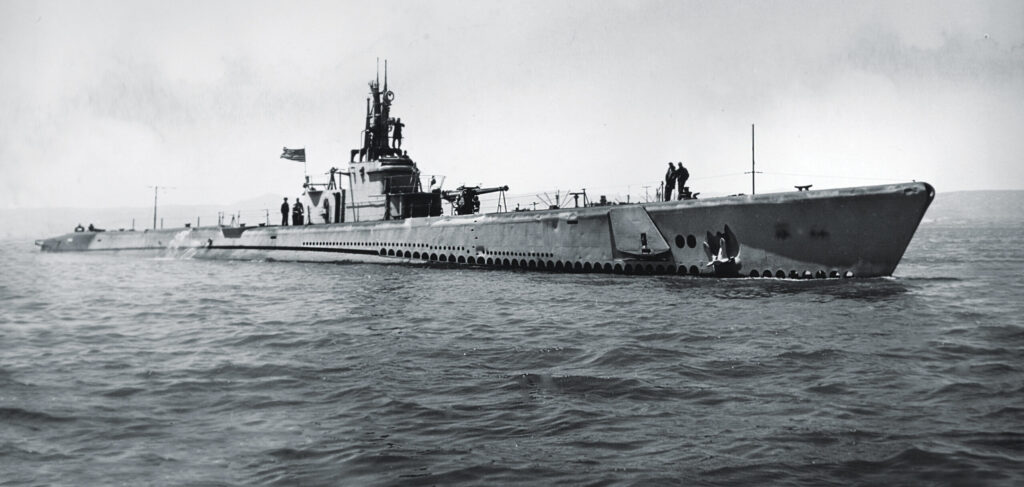

The men chopped up the Purple machine and dumped the pieces into deep water in Manila Bay. They saved the IBM equipment because Lietwiler wanted to use it in Australia. He assigned Ensign Ralph E. Cook, a former IBM engineer, to disassemble the equipment and pack it in crates so they could take it with them on a submarine. In case the Japanese ended up capturing the machines, Cook decided to create “a complex puzzle” for anyone trying to reassemble the equipment. He cut the devices’ cables and labeled their dozens of wires in a distinctive way that only he understood. To create further confusion, he threw some random parts into the crates.  The navy decided that submarines offered the best option to evacuate the Corregidor codebreakers. The USS Seadragon (SS-194) made two trips to the island. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The navy decided that submarines offered the best option to evacuate the Corregidor codebreakers. The USS Seadragon (SS-194) made two trips to the island. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The navy decided that submarines offered the best option to evacuate the Corregidor codebreakers. The USS Seadragon (SS-194) made two trips to the island. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The navy decided that submarines offered the best option to evacuate the Corregidor codebreakers. The USS Seadragon (SS-194) made two trips to the island. (Naval History and Heritage Command)On April 3, the Japanese launched a final offensive on Bataan, slicing through the American and Philippine lines. By April 8, Bataan’s commander, Major General Edward P. King Jr., decided he had no alternative but to surrender the next day. Once Bataan surrendered, Corregidor’s days would be numbered.

On the evening of April 8, Radioman Burnett answered the phone in the tunnel. “Sid, run like hell,” the caller said. “We are loading out in a few minutes.” The last 21 men of Station Cast scrambled onto a waiting truck and rode to the dock.

Yeoman Chamberlin described the scene that awaited them as “Dante’s Inferno PLUS.” Explosions rocked the ground and lit the night sky as the Bataan garrison destroyed its fuel and ammunition dumps in anticipation of surrender. In an attempt to give the defenders some breathing room, Corregidor’s artillery roared at Bataan, with muzzle flashes leaping 100 feet into the sky. Even nature got involved, as an earthquake shook the area.

When Chamberlin looked at his comrades, he saw a “ragtag bunch in worn, torn dungarees or khakis, underweight from malnutrition….” The accumulated stress showed, he said, and the men’s faces bore the “spectral look we came to call ‘The Corregidor Stare.’”

The men boarded a waiting submarine, the Seadragon, but there wasn’t enough time to load the crated IBM equipment before the submarine shoved off at 9:57 p.m. Once underway, the sub’s crew treated the codebreakers like royalty, showering them with cigars, candy, and cookies, delicacies that were unknown on Corregidor. They even let the evacuees use their bunks, and the men got their first good night’s sleep in months. There was also one unexpected passenger. In the chaos of the evacuation, a machinist’s mate from Corregidor had snuck onto the submarine as a stowaway, preferring a stay in the brig to a Japanese prison camp. Captured U.S. soldiers are led away by the Japanese after Corregidor fell on May 6, 1942. Many of the men pictured here probably died in Japanese captivity, a fate the codebreakers managed to avoid. (National Archives)

Captured U.S. soldiers are led away by the Japanese after Corregidor fell on May 6, 1942. Many of the men pictured here probably died in Japanese captivity, a fate the codebreakers managed to avoid. (National Archives)

Captured U.S. soldiers are led away by the Japanese after Corregidor fell on May 6, 1942. Many of the men pictured here probably died in Japanese captivity, a fate the codebreakers managed to avoid. (National Archives)

Captured U.S. soldiers are led away by the Japanese after Corregidor fell on May 6, 1942. Many of the men pictured here probably died in Japanese captivity, a fate the codebreakers managed to avoid. (National Archives)As with the Permit three weeks earlier, the Seadragon received orders to seek targets in Philippine waters after picking up the codebreakers. At 4:49 p.m. on April 11, skipper W.E. “Pete” Ferrall spotted a Japanese destroyer near Subic Bay, north of Corregidor, and fired three torpedoes from a range of 1,800 yards. All missed, and the destroyer dropped six depth charges near the submarine. “[N]one very close,” Ferrall noted in his patrol log. He asked the evacuees if the attack had frightened them. “Hell, no,” Burnett answered. He knew that sweating out depth charges was better than the fate that had awaited him on Corregidor.

The Seadragon reached Australia on April 26. All the passengers, including the stowaway, were “most happy to walk ashore in a friendly port,” Ensign Cook said.

The enemy invaded Corregidor on May 5, less than a month after the last codebreakers had departed, and the American and Filipino defenders surrendered the next day. Naval intelligence suspected that the Japanese had a complete roster of Station Cast personnel, possibly seized when they overran the Cavite naval yard near Manila four months earlier. The enemy made diligent efforts to find the Station Cast personnel among the Corregidor prisoners, but by this time they were all safely in Australia, continuing their interception and decryption work in Melbourne under the name FRUMEL (Fleet Radio Unit, Melbourne). The Japanese did find the crated IBM machines that had been left behind and realized their importance. They took the equipment to Tokyo so they could get it working and study American codebreaking technology. Ensign Cook, however, had done his job well and the Japanese never figured out his idiosyncratic wiring system.

Station Cast’s discovery that “AF” was the Japanese designation for Midway paid huge dividends. In early May 1942, Station Hypo determined that Japanese forces were gathering for a major operation but didn’t know where they would strike. Days later, it intercepted messages referring to “invasion force AF” and the “AF occupation force.” Now it knew that Midway was the target. Forewarned, the heavily outnumbered Pacific Fleet ambushed the Japanese forces advancing toward Midway on June 4, 1942, sinking four enemy carriers and winning a stunning victory that changed the course of the Pacific war.

The Intercept Tunnel, home to Station Cast, didn’t survive the war intact. On February 16, 1945, U.S. forces landed on Corregidor to retake the island. Ten days later, as they mopped up resistance near Monkey Point, a large cache of Japanese explosives stored in the tunnel detonated. The blast was so powerful that it tossed a 34-ton M4 Sherman tank 50 yards through the air, killing most of the crew, and threw debris so far that some hit a destroyer 2,000 yards offshore. The explosion killed 50 G.I.s and wounded 150 more.

It was an ignominious end for the place where only three years earlier, a small band of dedicated and ingenious codebreakers had helped turn the tide of the Pacific war and put the United States on the road to victory.

No comments:

Post a Comment