Atlantic Council experts

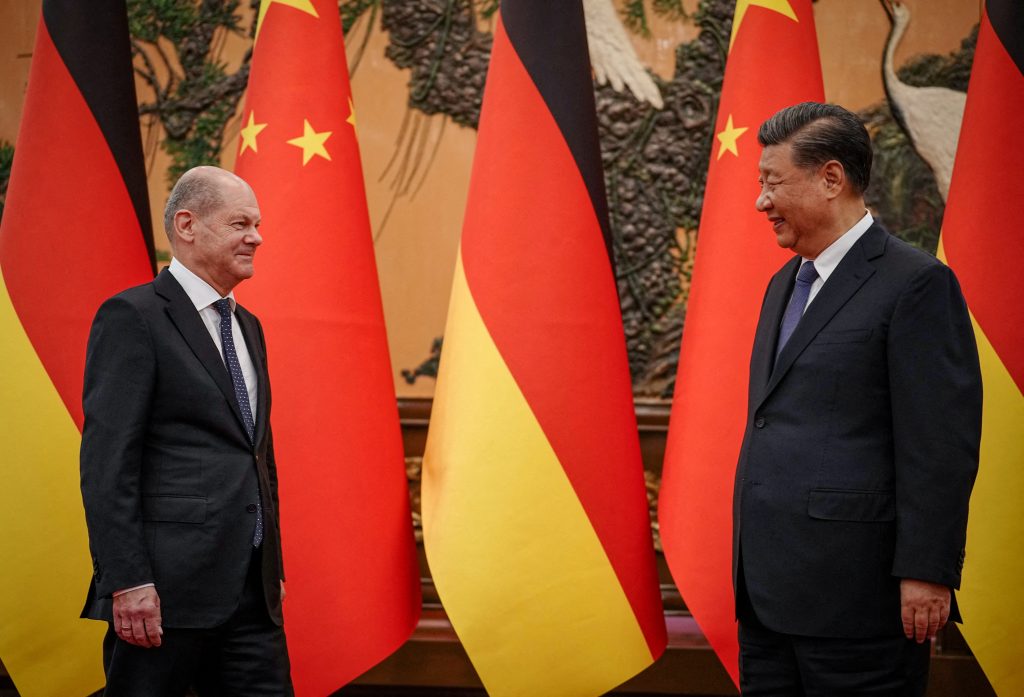

Is this another Zeitenwende? The German government adopted its first-ever strategy for relations with China on Thursday. Released after months of dispute among Germany’s three-party governing coalition, the strategy calls for measures to “de-risk” Berlin from the national security vulnerabilities of economic dependence on Beijing. The sixty-four page document reflects a wider shift in German foreign policy in the past year toward more strategic thinking—exemplified by Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Zeitenwende, or turning point, speech after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The China strategy arrives a month after the release of Germany’s inaugural national security strategy.

Below, Atlantic Council experts answer the most pressing questions about Germany’s new China strategy and what it will mean for relations between Europe and Asia’s largest economies.

1. Much has been made of the Zeitenwende prompted by Russia. Are we seeing a similar shift in German thinking on China?

Those expecting a Zeitenwende in Germany’s China policy from the country’s first-ever comprehensive China strategy will be disappointed. For China hawks in Washington, Germany’s new strategy will offer too much evolution and not enough revolution in Berlin’s approach to Beijing. The product of a contentious interagency process and partisan divergences in a complex three-way coalition, the new strategy starts with a familiar balancing act between calling out a more aggressive China and keeping Germany’s options open to continue its economic relationship with Beijing. It still tries to square the triangle of China as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival. The strategy acknowledges that “China has changed” and, along with it, German policy toward China must change, but fails to translate this into sufficiently specific or ambitious policy proposals. The document picks up European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s “de-risking” approach but also rules out decoupling. Throughout, it touts a coordinated approach at the European Union (EU) level—something China hawks among fellow member states might throw back at Berlin, which is seen by some as slow-walking a tougher approach to China in Brussels.

At the same time, a closer look reveals some important progress. Berlin’s China strategy avoids some of the biggest mistakes of its recently released national security counterpart. Most notably, it makes a more explicit assessment of the strengths and assets Germany can bring to bear in a more contentious Sino-German relationship. These are inevitably intertwined with EU competences, from the leverage the European single market affords Germany, to a proposed anti-coercion instrument and the new foreign subsidies regulation, to competition policy tools, tech regulation, and raw materials initiatives. Reflecting a recent government drive toward greater diversification, the document dedicates a separate chapter to “global partnerships”—from Africa and Central Asia to Latin America—and a proactive EU trade policy. In contrast to the national security strategy, it also makes explicit efforts to improve whole-of-government coordination, installs a regular (if somewhat vague) reporting mechanism on the strategy’s implementation, and highlights the need to strengthen expertise on China in the government and policy community more broadly.

—Jӧrn Fleck is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

With this strategy, Germany has put the Merkel-era naiveté toward China to rest. It highlights the need for Germany to become more resilient, invest in greater China competence, defend the global order, and engage with like-minded partners in order to outcompete China. The strategy also has a particular European component and takes a whole-of-government approach by increasing intergovernmental coordination on China. Not everybody in government, business, or academia will agree with the strategy, but it cements the slow shift that has taken place in German strategic thinking, which hopefully will continue.

—Roderick Kefferpütz is a nonresident senior fellow in the Europe Center and the director of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union office in Brussels.

The document confirms Germany’s adoption of a tougher approach toward a “changed” China under Xi Jinping. It underscores that Berlin will reduce dependencies and better protect its interests in the bilateral relationship even as Germany values continued engagement with Beijing to tackle global challenges. The question is whether this unvarnished take on the need for a transformed German approach to China will be matched with actionable government policies.

Notable elements include the conclusion that Beijing seeks to leverage economic and technological dependence on China to achieve political ends and that Berlin, in coordination with its EU partners, must commit to a “de-risking” strategy to reduce vulnerabilities across critical sectors and supply chains. Beijing has made clear its distaste for the “de-risking” terminology first employed by von der Leyen in March and which US and European leaders have since adopted, viewing it as just another version of “decoupling” that US allies may find more palatable to the ear. Indeed, the Chinese embassy in Berlin responded today that “forcibly ‘de-risking’ based on ideological prejudice and competition anxiety will only be counterproductive.”

—David O. Shullman is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and a former US deputy national intelligence officer for East Asia.

2. How involved militarily is Germany in the Indo-Pacific now, and what does this strategy tell us about how that will change?

The strategy takes an incredible leap forward! This is a welcome change from the national security strategy, which hardly mentioned the Indo-Pacific at all. In the China strategy, Germany is starting to take a “one-theater” approach to China, linking the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions. On several occasions, the strategy notes the challenge posed by the Sino-Russian relationship and explicitly mentions that “developments in the Indo-Pacific can have a direct impact on Euro-Atlantic security.” In this context, Germany wants to increase its presence as a security actor, aiming to expand military cooperation and arms exports in the Indo-Pacific.

—Roderick Kefferpütz

3. How does Germany’s China approach compare with that of its European neighbors and the United States?

One notable aspect of Berlin’s new strategy is how extensively and explicitly it’s tied into the EU’s overall approach to China, signaling to Chinese leaders that they may be facing a less favorable environment—at least in Berlin—for trying to create divisions within the EU and undermine a stronger and more unified approach toward China. Germany’s strategy uses multiple sections to lay out how its approach is embedded within a broader EU strategy and articulate a vision for strengthening the EU’s capacity for contending with China.

Many of the elements of Germany’s strategy for dealing with China as a “partner, competitor, and systemic rival” echo the recommendations that von der Leyen laid out earlier this year, such as enhancing domestic economic competitiveness and resilience and strengthening coordination with like-minded partners.

—Colleen Cottle is the deputy director of the Global China Hub and a former Central Intelligence Agency official.

The released strategy suggests divisions within the government over what role the transatlantic relationship plays when it comes to China. Earlier versions of the strategy mentioned the transatlantic relationship roughly twice as much and stated that the transatlantic partnership “plays a decisive role in a successful China policy.” This has been artificially toned down and reworded to “coordination with Germany’s closest partners is fundamental to our foreign policy; this also applies to our policy-making with and vis-à-vis China. Both the transatlantic alliance and the close partnership built on trust with the United States, including in the G7, is of tremendous importance for the EU and for Germany.”

The earlier leak also highlighted that “Germany, the EU and our valued partners are in a global systemic competition with China,” while the published version says “China has entered a geopolitical rivalry with the United States,” indirectly suggesting that Germany is standing on the sidelines. But this is not the case, as the strategy makes clear.

Germany takes a leadership role in this strategy by taking a networked, allies-based perspective. The strategy notes that its China policy is part of a joint EU policy on China, aims to Europeanize Germany’s approach to China, and even highlights that countries wishing to join the EU should align their approach to China with the bloc’s. Germany defines the China challenge in the context of different regions of the world and at the level of global institutions, regularly identifying valuable partners in this regard.

—Roderick Kefferpütz

4. What do we expect the reaction to be in Beijing?

Chinese leaders will note the call for German companies to “internalize” risk calculations as they consider current and future investments in China—indicating that the government may not bail them out in the event of geopolitical events, such as a crisis over Taiwan. The strategy includes language on the role that export controls and investment screening play in ensuring economic engagement with China does not bolster its military capabilities—highlighting concerns around Beijing’s military-civil fusion strategy—or “encourage systematic human rights violations in China.”

Beijing will also take note of the strategy’s call for stepped up engagement with Taiwan and welcoming of its greater participation in international fora, albeit while still reaffirming Germany’s one-China policy. The strategy mentions Germany’s growing security role in the Indo-Pacific, along with the need for differences over Taiwan to be settled peacefully. Importantly, the document also highlights that China is a “systemic rival” that seeks to upend the rules-based international order.

Chinese leaders, however, will remain hopeful that the strategy’s tough rhetoric will not be matched by government action. The lack of specifics on binding requirements to curtail German economic dependence on China, restrict outbound investment, or adopt tougher export control measures will bolster such hopes. Beijing will view the document’s reiteration of the need for continued economic engagement, combined with the fact that China remains Germany’s top trading partner and companies like BASF and Volkswagen have pledged to expand investment in China, as indicators that it retains leverage to prevent Berlin from aligning with Washington’s more hardline China policies. Beijing will also be attentive to the apparent daylight between those in government advocating for a tougher China policy and Scholz himself, who visited Beijing in November accompanied by a sizable business delegation and recently expressed the view that the government has a limited role in any de-risking policy.

Beijing is betting that, despite the strong rhetoric here, government inaction and economic realities in Germany will offer opportunities to steer Berlin back toward the more pro-China position of years past.

—David Shullman

Beijing will be watching closely to see how this strategy translates into concrete action. It will also be looking for opportunities to try to soften or slow roll any disadvantageous measures by leveraging German companies’ continued strong reliance on the Chinese market—a shortcoming identified in this strategy—and Berlin’s desire for continued cooperation with China in areas like climate change, sustainable development, global health, and broadly defined “economic and trade relations,” as laid out in the strategy.

No comments:

Post a Comment