Andrew Latham and Shweta Shankar

In the last three decades, China has become the focus of intense debate within U.S. foreign policy circles. Beijing’s peaceful rise to power has turned into an aggressive overreach of power over the last few years, sparking concerns about China’s future behavior as a great power. A deeper look into the relationship between the Chinese Communist Party and the United States reveals a number of dynamics that could be detrimental to global peace.

In her newly released book, Overreach: How China Derailed Its Peaceful Rise, Susan L. Shirk, founding chair of the 21st Century China Center, wades into the debate, writing that “China’s aggressive posture in world affairs and its relentlessly tight grip on domestic society are leading to what it most fears — a return to the politics of containment.”

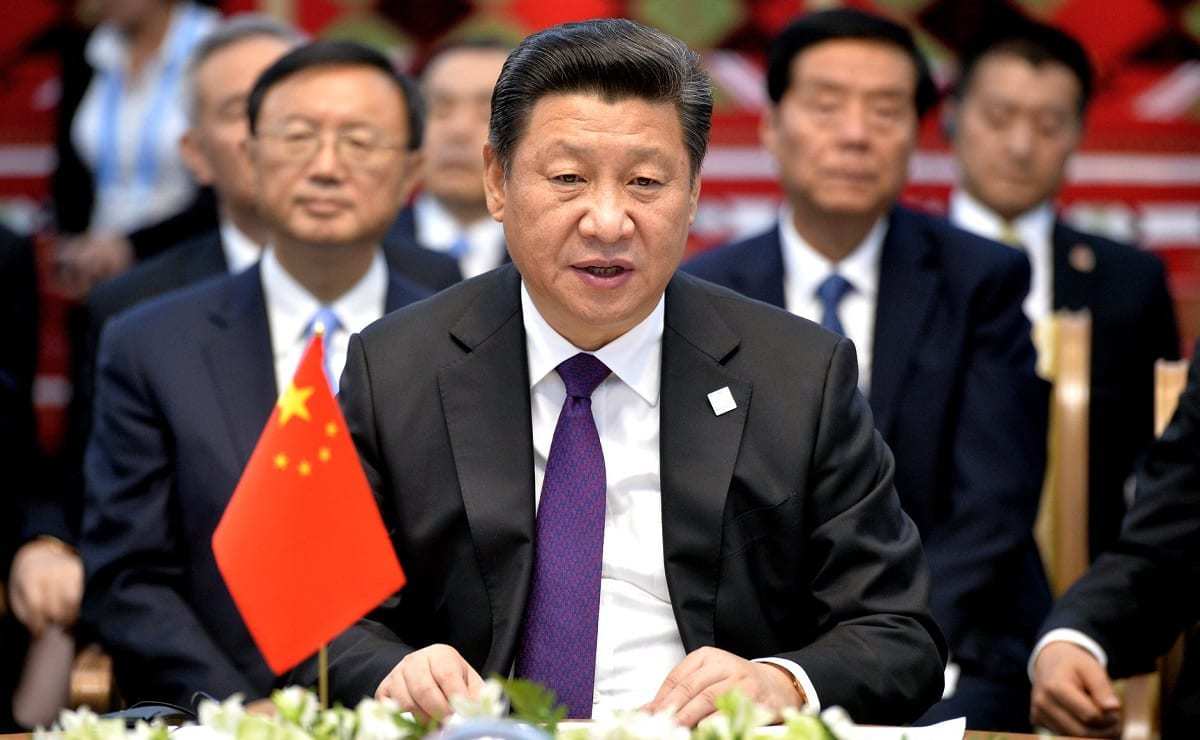

Specifically, Shirk argues that Chinese President Xi Jinping “is quite comfortable using China’s huge market power and deep pockets to suck up advanced technologies from abroad and into China. The aim of achieving self-reliance in semiconductors, batteries, and other crucially important technologies has become increasingly overt. With the hands of the state so obviously orchestrating this massive effort, it is no wonder that China is provoking a backlash in the United States and Europe.”. This and similar political realities, Shirk concludes, exert a considerable burden on China’s power, limiting its potential to display itself as a peaceful actor.

How China Has Evolved as a Power

This is good as far as it goes, but it is with respect to the tumultuous history of China’s rise that Shirk’s book really shines. On this theme, the author’s main argument is that the ease with which Xi reversed 30 years of institutionalization reveals the opacity of the Chinese political system.

Throughout the book, Shirk develops her thesis along many lines. She first argues that the Xi government has overreached, and in doing so it has weighed down China’s economy and generated worldwide turbulence. Its aggressive methods have harmed China’s global public image, resulting in an international backlash from numerous countries. Nations such as Australia, she argues, have been especially antagonized by China’s aggressive policies. “When the Australian government called for a full international inquiry of the origins of the [COVID-19] virus, the Chinese leaders punished it by cutting imports of Australian coal, wine, barley, lobsters, beef, and cotton.”

Moreover, Shirk illuminates the black box that is the CCP. “The leaders in China resist American calls for greater transparency in the belief that keeping Washington guessing about its capabilities and intentions makes China look stronger. Yet by refusing to share information, Beijing endangers itself because its signals may be misread.”

None of this bodes well for what she believes is China’s aspiration to become the world’s predominant power. In fact, China’s increasing aggressiveness and insensitivity, she concludes, is having the perverse effect of disrupting the support that China needs to maintain its role as a peaceful power.

A Challenging View of China

This is an ambitious book with much to commend. Shirk does an excellent job using anecdotes of her experiences to illustrate her thesis that China is reverting to the Mao era. Her description of the pushback generated by Beijing’s domestic and international policies is noteworthy. In Chapter 1 (Origins of Overreach), Shirk clearly outlines China’s mistakes. “Overreach began on three fronts: The economy, social control, and foreign policy,” she writes. In Chapter 2 (Deng’s Ghost), Shirk goes into details about the core issues of former Chinese President Deng Xiaoping’s leadership. Although he dismantled a lot of Soviet-style planning, “Deng was reluctant to bury Mao entirely. And he stopped short of establishing the independent courts, legislature, business firms, media, or civil society that could have checked the overwhelming power of the CCP.” The details emphasized throughout Shirk’s book highlight how the very policies China has adopted to advance its vision have generated precisely the kind of hostility they were afraid of.

Like every ambitious book, however, this one rests on a number of assumptions, assertions and arguments that are open to empirical challenge. To begin with, while the book is analytically rich, it is riddled with contradictions. It paints a very detailed picture of a totalitarian China that stays silent on the topics of human rights, democracy, and foreign policy. But Shirk contradicts herself on how the U.S. should proceed its relationship with China — specifically, what aspects of Chinese politics and economics should be the focus for those seeking to repair the relationship. “Although we must speak out against Chinese government abuses — to do otherwise would be antithetical to our identity as Americans — we should face up to the fact that we are unlikely to gain much traction on them,” she writes. Shirk’s suggestion of speaking out is contradicted by her own assertion that, “Political reform in China will not be realized through outside pressure. Domestic demand, not foreign prodding, brings out political transformations.” The belief seems to be that the world should speak out even knowing there will be little to no change, all the while remaining complacent about human rights violations in China. Domestic demand for change in China has not accomplished much in the last century. Indeed, the Tiananmen Square Massacre was a direct reaction to the domestic demands of Chinese citizens. The primary shortcoming of Overreach is thus Shirk’s contradictory statements regarding the future of U.S. policy towards China.

These shortcomings, however, are far from fatal. Shirk’s book is bursting with anecdotes, interviews, and analytical data that illuminate the black box that is the CCP. Overreach is a valuable contribution to international relations and foreign policy literature, spelling out an analytical framework that promises to demystify Chinese actions on the world stage.

Andrew Latham is a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN; a Senior Fellow with the Institute for Peace and Diplomacy in Ottawa, Canada; and a regular opinion contributor with The Hill, also in Washington, DC. Shweta Shankar is a researcher in the Political Science department at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN.

No comments:

Post a Comment