Janna Mantua

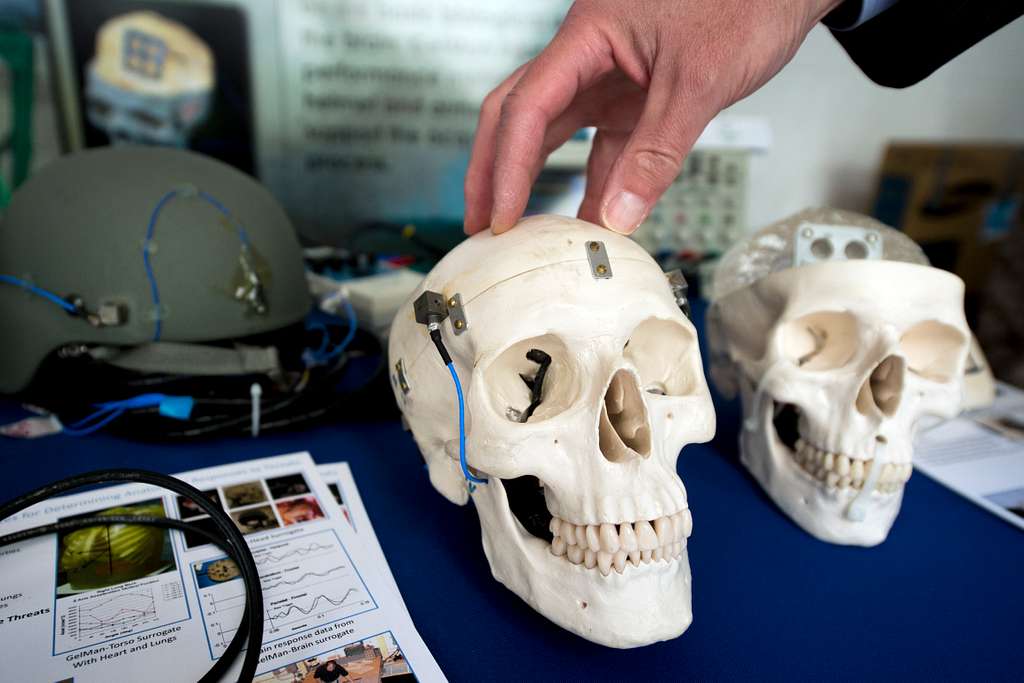

In 2016, US diplomats and CIA officers in Cuba abruptly began reporting symptoms of dizziness, nausea, and cognitive difficulties. Individuals suffering from this ailment – termed “Anomalous Health Incidents” by the US government, but more commonly known as “Havana Syndrome” – believed they had been victims of a coordinated attack. Scientists gathered information and performed calculations suggesting the symptoms may have been caused by a concentrated microwave weapon. Follow-up studies using MRI scans found Havana Syndrome sufferers exhibited evidence of traumatic brain injuries, suggesting their brains may have been physically damaged by the incident. Though the true cause of these injuries remains unknown, and though intelligence assessments have suggested there was no coordinated attack against these individuals, the attention these reports received ushered an important new question into the US national security zeitgeist: do our adversaries have a weapon that can cause brain damage from a distance?

The concept of attacking the thought processes and emotions of an adversary is as old as war itself. Generations ago, commanders sought ways to attack the adversary’s morale and will to fight. Today’s military leaders seek to do the same while using different terminology: achieving cognitive overmatch, controlling the information space, pursuing decision dominance, and, of course, winning the hearts and minds of specific populations. Though the concept is not new, the ways by which we create effects on cognition and emotion have changed due to new technologies and the pervasiveness of information.

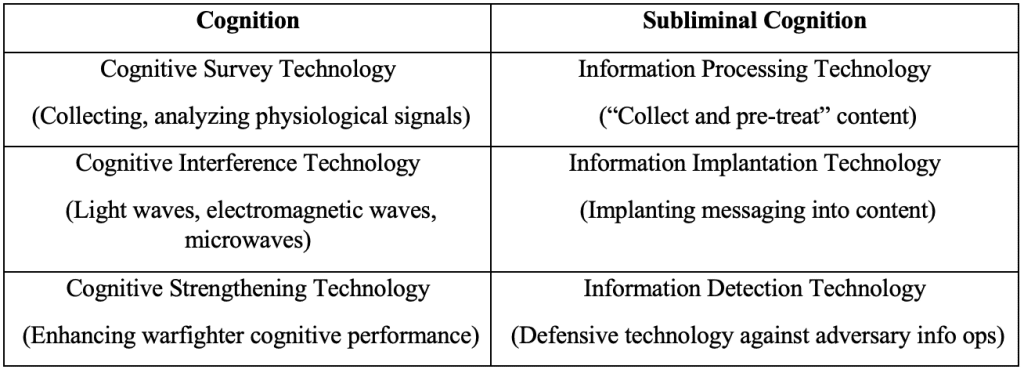

The DoD does not have a definition for Cognitive Warfare (CW), though NATO’s Allied Command Transformation defines it as “the activities conducted in synchronization with other instruments of power, to affect attitudes and behaviors by influencing, protecting, and/or disrupting individual and group cognitions to gain an advantage.” On the surface, this definition may look similar to the definition for Information Operations (now known as Operations in the Information Environment [OIE]), but a side-by-side comparison (Table 1) suggests CW is in fact a broader concept that contains a reference to “activities” outside of the information domain. Still, CW and OIE are often conflated. As recent as April of 2023, a NATO working group (the same group that created the definition for CW) published an article on CW that exclusively described threats from OIE without mentioning other CW-related adversarial activities.

Thus, it’s worthwhile to review the activities making up CW to promote a clearer understanding of this critical concept; and that is what this piece aims to do.

Table 1

China’s Cognitive Warfare Activities

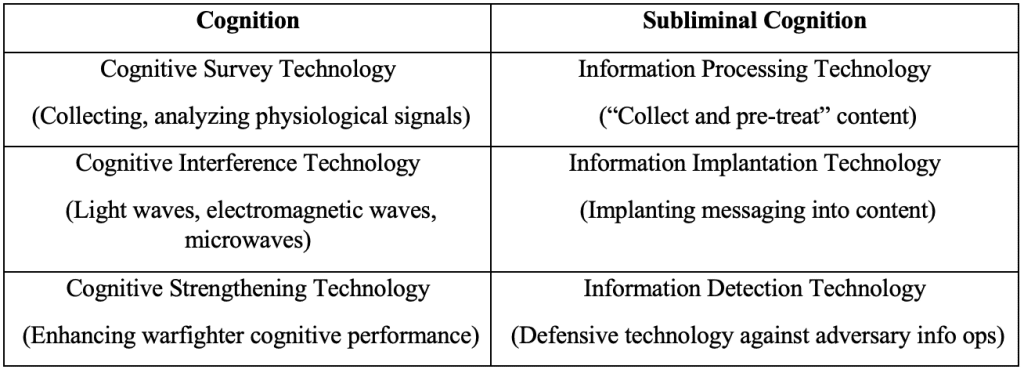

To understand what CW entails, we must look no further than the activities of our adversaries. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has a broad, coherent Cognitive Warfare doctrine (often described as their Cognitive Domain Operations doctrine) that includes several elements outside of the information domain. Table 2 provides an overview of their framework, which includes technologies and capabilities in two categories: Cognition and Subliminal Cognition.

The Cognition category’s first focus is Cognitive Survey Technology, which includes the collection and analysis of physiological brain signals. Why might this be useful? In theory, if cognitive processes can be distilled into quantifiable events or signals, they can be tracked and more easily modulated. The proper quantification of brain signals could allow for better internal or external control over cognitive processes. Additionally, properly quantifying brain signals is critical for human-machine teaming. In the non-military domain, effective human-machine teaming is already in use for some individuals with artificial limbs. Certain types of artificial limbs can be controlled by brain signals, just like an organic limb. On the battlefield, effective human-machine teaming could entail linking warfighters directly to weapons systems, which may then enable quick and seamless control of weapons through the mind.

Table 2

The second focus of PRC’s Cognition category is Cognitive Interference Technology. This includes technology that is intended to cause physical interference or damage to the brain, including (you guessed it) microwave technology. The development of technologies to cause physical disruption to the brain, particularly from a distance, could be a game-changer: US decision-makers could be targeted just prior to the onset of a conflict, or a large group of decision-makers could be targeted broadly to degrade the effectiveness of the DoD and intelligence community.

On the flip side, an additional focus for PRC is Cognitive Strengthening Technology, or technologies that enhance cognition and emotion. These technologies may include new medications for increasing focus or mood, brain implants that “read your thoughts” (similar to Elon Musk’s proposed Neuralink device), or training environments that increase the cognitive ability of warfighters. Enhancing cognition in this manner could increase warfighter decision-making speed and increase cognitive resilience under stressors (e.g., sleep loss). These bio-enhancements could keep soldiers fighting harder, for longer, in more austere conditions.

The Subliminal Cognition Arm of PRC’s Cognitive Warfare Doctrine appears simply to be an OIE playbook. It includes the development of technology and methodologies that prepare and disseminate content that is in favor of their narrative. It also includes defensive technologies that can detect adversarial information threats. The PRC is already conducting visible activities in line with their OIE doctrine. For instance, they employ internet commentators, or “wumao,” to spread propaganda online that is consistent with the state’s interests. They also selectively amplify the voices of influencers, including Westerners, who are promoting China of their own volition.

Taking these elements together, we can begin to envision how PRC could leverage CW during a hybrid-warfare scenario against the US. In a hypothetical future scenario in which PRC invades Taiwan, PRC could begin their campaign by using IOE to soften their targets. First, a misinformation campaign could be conducted to affect Taiwanese citizens psychologically with the intent of degrading their morale (in fact, this is reportedly already happening today). Next, deepfake videos of a false-flag operation could be used to divide the American public and lawmakers over US involvement in the Pacific. Brain-damaging weapons could be used against senior leaders of INDOPACOM, CYBERCOM, SOCOM, and SPACECOM to decrease readiness and sow discord within each critical Combatant Command. Soon after, upon the initiation of conflict, the PRC’s human-machine teaming capabilities could enable seamless Observe, Orient, Decide, Act, or OODA, loops that support PRC’s anti-ship campaign, thereby denying the US entry into the operational theater. PRC’s bio-engineered “super soldiers” may be able to fight harder and longer than US warfighters already in theater, reducing remaining opportunities that the US has to protect Taiwan.

How will the DoD counter these capabilities?

DoD Cognitive Warfare Activities

Fortunately, the US is not turning a blind eye to this threat. The DoD is also focused on CW, albeit in a less coherent manner.

Since the early 2010s, the US has largely focused CW efforts on countering adversarial cyber OIE. There is good reason for this. Information threats in the cyber domain are currently the most blatant and damaging form of CW, and these threats will likely be amplified by the advent of widely available artificial intelligence technologies (e.g., deepfakes, ChatGPT). In response to cyber OIE threats, the DoD has made great strides in incorporating OIE into doctrine. For instance, the DoD approved the Global Integrated Operations in the Information Environment EXORD in 2018, and it recently made updates to Joint Publication 3-04 (Information in Joint Operations). These documents provide guidance and authorities that allow the DoD to prepare for offensive and defensive OIE.

The DoD also has several ongoing research and development efforts focused on human-machine teaming and cognitive strengthening. Army Futures Command (AFC) has outlined several initiatives along this line, including the development of “automated battle management tools [that] minimize the human cognitive overload through a ‘human on the loop’ interface where sensors, shooters, and firing solutions converged from multiple networks across domains.” Additional efforts from AFC focus on developing technologies and capabilities that will allow soldiers to sustain cognitive alertness and performance under stressors through the use of “wearable medical sensors” that can detect cognitive fatigue. Similar efforts to enhance cognition are being conducted by the Air Force Research Lab and the Naval Health Research Center.

However, for one particular reason, our adversaries may develop CW capabilities where the DoD cannot. DoD technologies and capabilities will inherently be limited by the collective ethical standards of the US. The US biomedical research community follows ethical guidelines described in the Declaration of Helsinki. The declaration states, among other things, that human research requires informed consent, and there should be no undue risk to research participants during experimentation. These ethical guidelines are intended to protect against the repeat of biomedical atrocities conducted by German military scientists during WWII. Biomedical researchers in countries that do not adhere to these principles may be willing and able to push ethical boundaries in order to develop game-changing CW capabilities. In fact, PRC is reportedly already doing so through non-consensual genetic modification and biomedical alterations. Adversaries that are willing to allow this type of research may surpass US capabilities in the CW domain.

The Way Ahead

As noted, the DoD has been working to create opportunities for both offensive and defensive operations in the OIE. Still, the DoD has a lot of ground to cover in the information space. It will need to be more flexible in its approach to conducting and countering OIE, and it will also need to be creative in its approaches. For instance, the DoD should consider leveraging irregular online assets such as “influencers” and grassroots cyber-insurgents (e.g., North Atlantic Fellas Organization, or NAFO) to counter OIE. As noted, the PRC is using state-funded and grassroots influencers to promote PRC-friendly messaging. To remain competitive, the US will need to identify and utilize its own online influencers without violating the sensitivities that US citizens have about state-sponsored coercion.

The DoD must also create a working definition and framework for CW that incorporates activities outside of OIE. The development of a coherent framework for CW will enable the identification of threats and capability gaps. Without this, the DoD will not be coherent and comprehensive in its approach to achieve dominance in this space.

Lastly, the DoD will need to dedicate additional funding for research and development focused on CW. It is imperative for DoD scientists and industry partners to be innovative and push the boundaries of cognitive science and neuroscience while also remaining within the ethical boundaries of human subject research. At the same time, the DoD must be aware that other nation states may not be adhering to the same ethical guidelines; we must be prepared to defend against potentially superior technologies that are achieved through unethical means.

Janna Mantua has a PhD in Behavioral Neuroscience and is completing a Master’s degree in Military Strategic Studies with a concentration in Irregular Warfare. She is a member of the research staff at a defense think tank in the Washington, D.C. area where she contributes to projects focusing on offensive and defensive influence operations and is co-chair of the Influence Operations Working Group.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

No comments:

Post a Comment