Nadia Schadlow

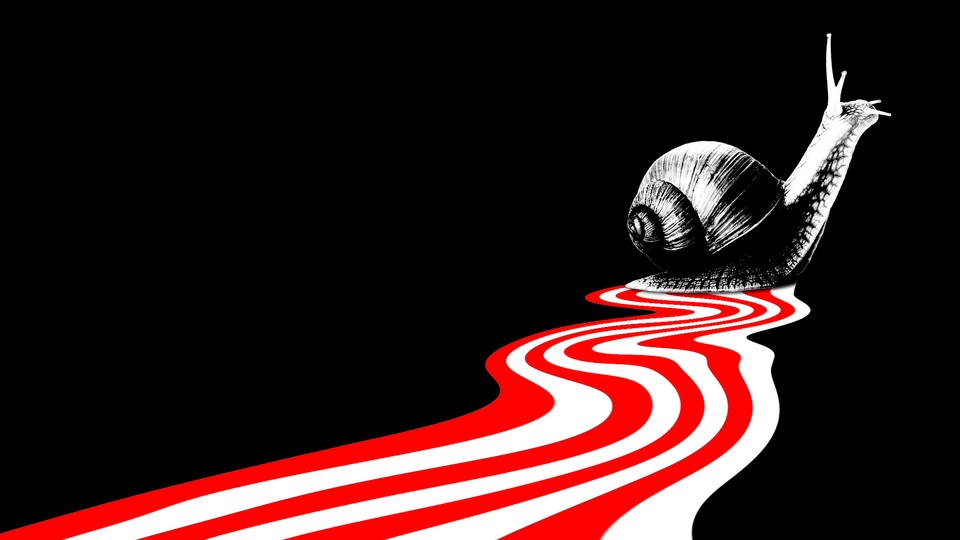

Time and time again, in one sector after another, we articulate strategies and set objectives, but we usually fall short, because we’ve failed to take into account the crucial element of time. Tasks we once accomplished swiftly now drag on for years. Problems we once resolved efficiently now prove interminable. Without incorporating time into our strategic calculations, we will always be too late.

I saw this firsthand while I worked at the White House. In 2017, as deputy national security adviser for strategy, I helped write the U.S. National Security Strategy. I knew that actually implementing the initiatives it detailed would be harder than writing it. Presidential executive orders and White House strategies are merely aspirational until they are linked to budgets, and until tasks are assigned to the organizations that must implement them. But even that is not enough. The NSS outlines priorities, but it does not specify when they must be achieved or provide a mechanism to track how long they are taking. The result is a problem that plagues Democratic and Republican administrations alike, as their initiatives aren’t executed swiftly enough to accomplish what they are intended to achieve. Examples abound:

American leaders consistently emphasize the need to reduce dependence on China for crucial minerals, and although we have abundant domestic resources, it still takes well over a decade, on average, to open a new mine in the United States.

Top military leaders lament that we have lost the art of moving fast and that unless we accelerate required changes, we won’t be prepared to deter and win wars. China is acquiring high-end weapons systems and equipment five to six times faster than the United States. As we continue to provide Ukraine with ammunition and other military equipment, we struggle with replenishing our stockpiles of arms and munitions. For some weapons systems, replenishment will take at least five years, just to restore stocks that were already inadequate to sustain a major conflict. This is particularly problematic, because the United States might run out of certain munitions in less than a week should conflict with China erupt over Taiwan.

We desperately need more ships, but maintenance delays for naval vessels result in, as one retired admiral put it, “the equivalent of losing half an aircraft carrier and three submarines each year.” Those numbers continue to move in the wrong direction. And many of our weapons systems depend on software upgrades; any delays can render them obsolescent.

The problems are not limited to national security. Climate change has been deemed an existential threat for decades, but we have made little progress in mitigating the effects of global warming. It is hard to reconcile an existential threat with glacial progress. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services struggles to process immigrants in a timely fashion, even with staffing increases and technological improvements. Similarly, U.S. officials have complained about the lack of qualified STEM workers for years, without succeeding in addressing the problem.

The United States finds itself unable to get important things done at what military leaders have called the “speed of relevance.” New technology is disrupting existing political, economic, and regulatory architectures faster than they can be rebuilt, exposing a growing gap between the promises of leaders and their ability to deliver. This gap between promises and outcome creates cynicism at home and abroad. Americans are skeptical that government can adapt and reform, given the speed of technological change. Internationally, friends and allies are questioning U.S. competence. Our rivals, in turn, register our inability to deliver, weakening deterrence.

Time wasn’t always a problem as the Pentagon itself proves. The construction of what is still by far the largest office building on Earth took just 16 months. The construction supervisor, Leslie Groves, was known as “the biggest S.O.B around,” a man who “had the guts to make difficult decisions,” as one subordinate later recalled. He demanded decisions in 24 hours or less, or an explanation. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s scientific adviser Vannevar Bush said that nothing should stand in the way of a program to build an atomic bomb “at the maximum speed possible.” The resulting Manhattan Project, directed by Groves, took about three years.

Later, President John F. Kennedy’s Apollo program put humans on the moon within a decade, spinning off thousands of new innovations, such as integrated circuits and solar panels. It required building a pair of major facilities—the Johnson Space Center and the Kennedy Space Center—each within a few years. In the 1950s, the Air Force fielded six new fighters from five different manufacturers in only five years, and during the early years of the Cold War, generations of ICBMs came and went within a decade. The revolutionary Minuteman missile was conceived in the late ’50s and deployed in the early ’60s.

In the diplomatic realm, the Marshall Plan was announced in 1948, and within three years, it had provided nearly $15 billion to rebuild Western Europe. Inspired by his World War II experiences—having seen the “superlative system of the German autobahn”—President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation funding the U.S. interstate highway system in June 1956, and within 10 years, it was substantially completed.

These successes shared a common absence. Sprawling bureaucracies and stifling regulations had not yet materialized. The Defense Department could act quickly to buy the tens of thousands of microchips from Texas Instruments that it needed for the Minuteman missile. In the fall of 1962, the Air Force started looking for a new computer to guide the Minuteman II, and by the end of 1964 it had found one and test-fired the first missile.

Consistency in funding was crucial too. For instance, the overall cost of the Apollo space program actually declined as work shifted from research and development into production and operations. The program had the money it needed when it needed it, and the funding was sustained for years.

Moreover, in many of these cases, individuals were given the power to make decisions and to build strong teams quickly. The Marshall Plan’s administrator, Paul Hoffman, could hire qualified experts within weeks, recruiting the best from government, academia, and industry to staff each mission area. The Marshall Plan was a “business plan to be carried out by businessmen,” as one media executive put it. The Apollo program assembled young engineers and scientists with similar speed. Today, most of these hiring practices would be illegal.

We can no longer live off the accomplishments of past generations. To compete in today’s world, and to protect American interests, we must take time into account.

Calls for bureaucratic reform are nothing new. The Defense Department alone, for instance, has seen well over 150 efforts to upgrade acquisition systems, speed up processes, and buy what it needs when it’s needed. Empowering leaders to take greater risks can speed up processes. And experts have long warned of the dangers of compliance cultures that cripple organizations, as individuals spend more time checking boxes than actually getting results.

Such reform efforts will continue. Some may even succeed. But there is an additional approach that we might pursue: incorporating time as a foundational element of strategy.

In practical policy terms, this would mean including time as an input into policy promises and initiatives, just as we do other factors, such as funding and personnel. Given the abundance and granularity of data today, and the availability of new analytical tools such as large language models, this input is possible in a way that it was not in the past.

What we might call time-sensitive strategies have several benefits. They force policy makers to account for time, which in turn helps them define objectives realistically. These strategies could impose a sense of discipline too—like the Gantt charts of the early 1900s, which helped managers track the time required for each stage of a complicated process. Policy makers would need to account not just for what needs to be done, but also for when it needs to be done.

Time-sensitive strategies would also force greater transparency. Americans deserve to know whether a promise can be fulfilled tomorrow, or whether it will likely take many years. This could in turn reduce cynicism and might appeal to the best of Americans’ desire to improve and innovate and fix things, allowing them to ask why certain tasks take so long and advocate for improvements.

And finally, such strategies might reveal flawed assumptions, and drive decision makers toward more creative approaches. If leaders are forced to ask why things are taking so long, they in turn will identify persistent regulatory, legislative, and funding obstacles, and explain how they will be removed or overcome. Often, we need new ideas less than new ways of accomplishing long-standing goals.

If we remain naive or willfully ignorant about the role that time plays in success, the promises of our political leaders will remain merely performative.

But we need more than performative promises. The major technological and geopolitical challenges we face demand that the United States act faster. Advances in quantum technologies will render obsolete entire communication networks that depend on encryption. Precision-guided weapons and autonomous systems like drones have made American bases around the world vulnerable. The ability to shift supply chains to improve U.S. resilience and reduce our vulnerabilities depends on the ability of the United States to build mining and manufacturing facilities more quickly.

To meet its needs at home, and protect our interests around the world, Washington needs to deliver on time.

Nadia Schadlow, a former deputy national security adviser for strategy, is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.

No comments:

Post a Comment