Charlie Vest and Agatha Kratz

In recent months, growing tensions in the Taiwan Strait as well as the rapid and coordinated Group of Seven (G7) economic response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have raised questions—in G7 capitals and in Beijing alike—over whether similar measures could be imposed on China in a Taiwan crisis. This report examines the range of plausible economic countermeasures on the table for G7 leaders in the event of a major escalation in the Taiwan Strait short of war. The study explores potential economic impacts of such measures on China, the G7, and other countries around the world, as well as coordination challenges in a crisis.

The key findings of this paper:In the case of a major crisis, the G7 would likely implement sanctions and other economic countermeasures targeting China across at least three main channels: China’s financial sector; individuals and entities associated with China’s political and military leadership; and Chinese industrial sectors linked to the military. Past sanctions programs aimed at Russia and other economies revealed a broad toolkit that G7 countries could bring to bear on China in the event of a Taiwan crisis. Some of these tools are already being used to target Chinese officials and industries, though at a very limited scale.

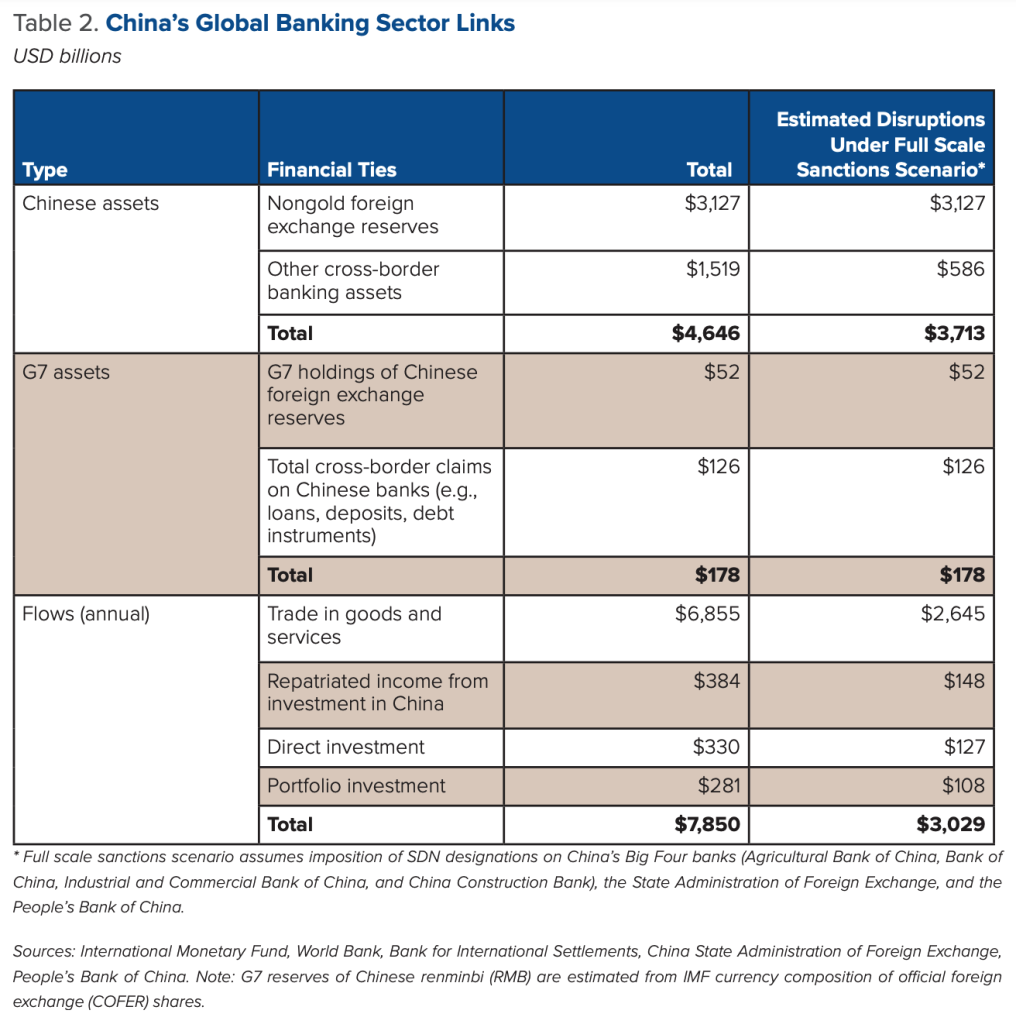

Large-scale sanctions on China would entail massive global costs. As the world’s second-biggest economy—ten times the size of Russia—and the world’s largest trader, China has deep global economic ties that make full-scale sanctions highly costly for all parties. In a maximalist scenario involving sanctions on the largest institutions in China’s banking system, we estimate that at least $3 trillion in trade and financial flows, not including foreign reserve assets, would be put at immediate risk of disruption. This is nearly equivalent to the gross domestic product of the United Kingdom in 2022. Impacts of this scale make them politically difficult outside of an invasion of Taiwan or wartime scenario.

G7 responses would likely seek to reduce the collateral damage of a sanctions package by targeting Chinese industries and entities that rely heavily and asymmetrically on G7 inputs, markets, or technologies. Targeted sanctions would still have substantial impacts on China as well as sanctioning countries, their partners, and financial markets. Our study shows economic countermeasures aimed at China’s aerospace industry, for example, could directly affect at least $2.2 billion in G7 exports to China, and disrupt the supply of inputs to the G7’s own aerospace industries. Should China impose retaliatory measures, another $33 billion in G7 exports of aircrafts and parts could be impacted.

Achieving coordination among sanctioning countries in a Taiwan crisis presents a unique challenge. While policymakers have begun discussing the potential for economic countermeasures in a Taiwan crisis, consultations are still in the early stages. Coordination is key to successful sanctions programs, but high costs and uncertainty about Beijing’s ultimate intentions will make stakeholder alignment a challenge. Finding alignment with Taiwan in particular on the use of economic countermeasures will be central to any successful effort. G7 differences on Taiwan’s legal status may also prove a hurdle when seeking rapid alignment on sanctions.

Deterrence through economic statecraft cannot do the job alone. Economic countermeasures are complementary to, rather than a replacement for, military and diplomatic tools to maintain peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. Overreliance on economic countermeasures or overconfidence in their short-term impact could lead to policy missteps. Such tools also run the risk of becoming gradually less effective over time as China scales up alternative currency and financial settlement systems.

I. Introduction

For decades, Taiwan’s deepening economic ties with China and the rest of the world have helped maintain peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. Mutual trade and investment have spurred rapid economic growth and—at least until recently— appeared to diminish the likelihood of military conflict.

The long-standing guardrails around the China-Taiwan status quo have weakened. Intensifying US-China geopolitical tensions, China’s increased use of military and economic tools to put pressure on Taiwan, Beijing’s draconian handling of Hong Kong, and evolving Taiwanese perspectives on their national identity and relationship with the mainland have all contributed to rising tensions. Taiwan’s presidential elections set for early 2024 increase the risk of escalation, as do both a rancorous US debate on China and political anxiety in Beijing in the face of a deteriorating economic outlook.

As concerns grow, so does awareness of the global economic stakes of a Taiwan crisis. Prior Rhodium Group research estimates that more than $2 trillion of global economic activity would be at risk of direct disruption from a blockade of Taiwan annually.1 This is a likely underestimate of the short- and long-term economic fallout of a full-blown crisis. In all cases, the scale of these likely global impacts—ranging from widespread goods shortages, mass unemployment, and a possible financial crisis—underscores the need for clear-eyed analysis about the costs of a conflict.

In this context, policymakers and business leaders around the world have begun discussing the potential role of sanctions and other economic countermeasures in a military crisis. The G7’s coordinated use of sanctions against Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine have highlighted the range of tools on the table. In Washington and other G7 capitals, as well as in Beijing, leaders are now considering the potential for, and implications of, sanctioning China. Yet G7 coordination in a Taiwan crisis would involve a different set of challenges. China’s economy is ten times larger and more globally interconnected than Russia’s, raising questions about the viability of joint economic countermeasures.

Given these open questions, the purpose of this report is to provide a data-driven and objective first look at the potential for a coordinated G7 response to a Taiwan crisis. It evaluates different economic statecraft tools and considers the global economic repercussions from their use. Based on an extensive series of in-person roundtable discussions in the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, interviews held with G7 policymakers and experts, and our own independent economic analysis, the report sets out the order of magnitude of what is at stake and the coordination that would be required for sanctions options to be effective.

While few US, European, and Chinese officials want to see tensions escalate in the Taiwan Strait, the past year has shown that situations previously regarded as highly unlikely can quickly materialize into a devastating reality. Understanding the scenarios and risks of using the tools of economic statecraft is not only a useful exercise, but also a critical step in ensuring all sides understand the full impact of actions that may be undertaken in a crisis.

II. The role of economic statecraft in a Taiwan crisis

A sense of heightened risk in the Taiwan Strait and the use of sanctions against Russia has led decision-makers around the world to reflect on the potential use of economic countermeasures against China in a Taiwan crisis. US lawmakers have already proposed legislation mandating sanctions on China in the event of an invasion of Taiwan.2 Surveys of European countries underline an increasing—if still minority—willingness to sanction China if it were to take military action against Taiwan.3 Officials in Beijing are asking these questions as well, with China’s State Council reportedly considering the potential for Western sanctions in a Taiwan crisis.4 The economic fallout from sanctions on Russia have also led business leaders and major banks to conduct contingency planning exercises exploring their exposures to a cross-strait crisis, including sanctions on China.

In defining what sanctions to use—if any—policymakers are likely to take a series of factors into consideration: what goals they are looking to achieve, what options are on the table to achieve those goals, and their relative impacts, costs, and limitations. This section reviews these factors and lays out the most likely options on the table.

Goals of economic countermeasures

Economic countermeasures—defined broadly here to include financial sanctions, export controls, and other restrictions on economic activity—can have a variety of objectives. They may aim to deter aggression, either by promising punitive economic actions in response to a transgression (deterrence by punishment) or by denying an adversary the technology or resources to engage in aggressive activity in the future (deterrence by denial). They may also aim to degrade an adversary’s ability or willingness to sustain aggression after it has begun.

The aim of economic countermeasures may evolve over time. The United States had long imposed export controls to limit the flow of military and dual-use technology to Russia. Immediately prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, the United States and allies threatened sanctions on Russia in a bid to deter military action. After the invasion, the focus of sanctions shifted to degrading Russia’s ability and willingness to continue the war. Sanctions may also have had a signaling effect that G7 countries were aligned and willing to bear prolonged costs in support of Ukraine.

As in the case of Russia, the United States and allies have limited the flow of arms and military technology to China in part to blunt its ability to engage in aggression against Taiwan long before a potential crisis. The proper design of these long-term restrictions is a matter of contentious debate in the field of export controls and technology policy, but is not the focus of this paper.

Some G7 partners are already communicating to China that actions short of an invasion could trigger economic countermeasures

Economic countermeasures might also be considered after a full-scale invasion of Taiwan to degrade China’s ability to sustain the conflict. In fact, interviews and roundtables highlighted near consensus about the fact that sanctions would be imposed on China were it to use military power to seize Taiwan. However, if the case of Russia is any guide, these sanctions take time to have an effect. Recent studies suggest that absent military intervention from the United States and allies, Taiwan is unlikely to withstand a full-scale invasion for the length of time necessary for sanctions alone to meaningfully degrade China’s military capacity.5

Some level of sanctioning might therefore also be contemplated in a crisis below the level of invasion, to deter further aggression. Some G7 partners are already communicating to China that actions short of an invasion could trigger economic countermeasures. These actions are the core focus of this report. While we do not identify specific triggers for economic action below invasion—because these are still intensely debated—they might include a military quarantine scenario, where the PRC restricts the free movement of ships or planes to Taiwan; acts of overt economic coercion such as wide-ranging punitive restrictions on cross-strait trade; and major cyberattacks or other disruptions to telecommunications networks on the island. Taiwanese officials have described some of these below-invasion scenarios as the most likely and pressing military risks to Taiwan’s sovereignty.6 Some of these “gray zone” actions, besides, come with high global economic costs that could warrant efforts by G7 nations to deter Chinese actions.7

Current economic statecraft tools

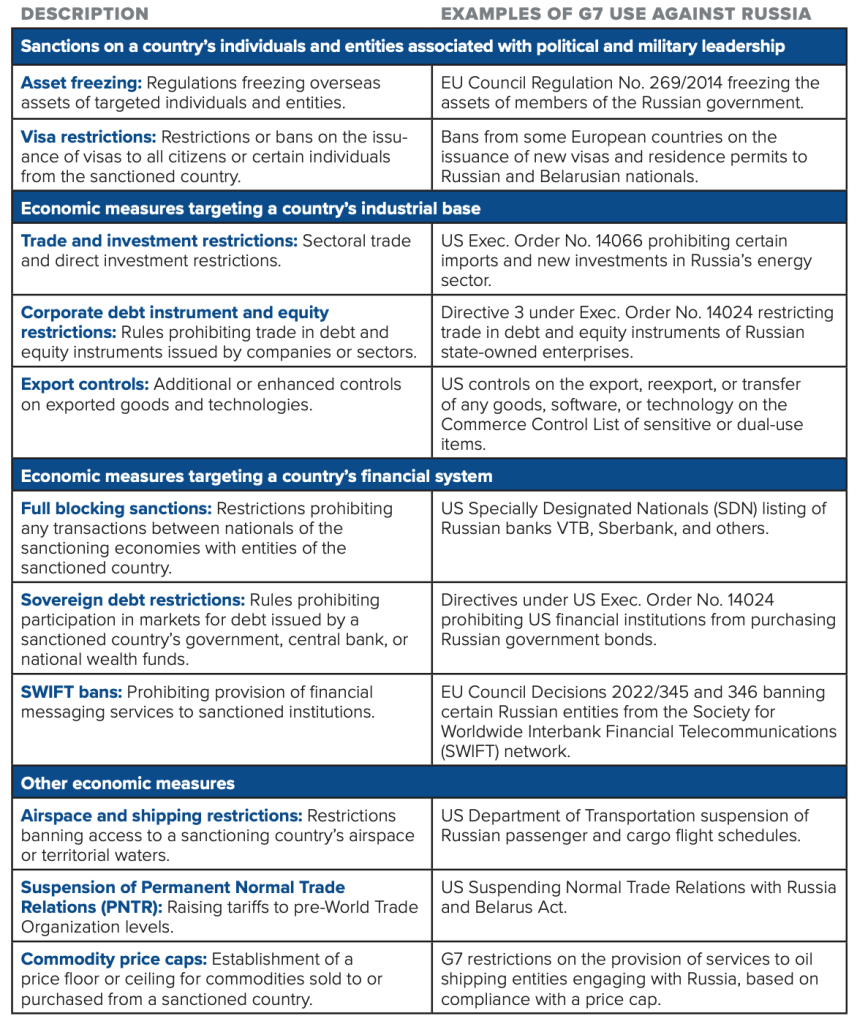

In looking to achieve these goals, G7 leaders have a range of tools available. Many economic countermeasures have been deployed in the context of previous crises (Table 1), including Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, making them useful starting points to assess potential future action.

In understanding whether these tools could also be deployed in a major cross-strait crisis, it is important to remember that some tools are already being used against China today, both by the United States and other members of the G7. Actions include, among others:Export controls including product-based and end-user-based controls on certain strategic technologies, such as semiconductors, integrated circuits, and supercomputing technology.8

Restrictions on the trading of debt and equity instruments in certain military-related companies under the Non-SDN Chinese Military Industrial Complex Companies List.9

Sanctions imposed on persons involved in the repression of minorities in Xinjiang, as well as small Chinese banks aiding Iran and North Korea in sanctions evasion.10

US and EU coordination of sanctions against Chinese firms involved in supporting Russia’s war on Ukraine.

While these measures are applied at a much smaller scale than they would be in a Taiwan Strait crisis, they illustrate the fact that G7 nations have already shown willingness to use economic measures against China when Chinese actions or policies were considered problematic. Importantly, these measures have been selective. From manufactured goods to inputs for electric vehicles, to machine tools, and pharmaceuticals, China is deeply embedded in global supply chains in a way wholly more complicated than Russia’s energy exports. At the same time, China’s reserves, capital controls, the state-owned banking sector, and abundant fiscal space provide the Chinese economy with critical buffers and economic defense mechanisms.

Tools in a future crisis

In imposing sanctions in a Taiwan crisis, G7 partners would seek to amplify existing measures taken against China and focus on asymmetric dependencies. Policymakers will likely look to the same types of targets described in Table 1, with varying intensity depending on the level of escalation, namely:Sanctions on China’s financial sector

Sanctions on individuals associated with the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and People’s Liberation Army (PLA)

Restrictions on industrial companies in sectors relevant to China’s defense industrial base

We take these three types of tools as our baseline for likely G7 countermeasures in a Taiwan crisis and analyze each in depth.

While these are the most likely sets of tools identified by experts based on past actions, future crises may bring new tools to the table too. Conversations with US and European officials made clear that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reshaped the contours of what was possible in the realm of economic statecraft. Just as blocking Russia’s central bank reserves and implementing an oil price cap were initially considered unrealistic, crises may spur discussions around new tools. Roundtable discussants raised options ranging from targeting casinos in Macau, which are regarded as havens of capital flight for China’s elite as well as illicit finance and money laundering; to imposing controls on China’s digital industries and firms, which power much of the country’s urban and consumer economy; to limiting access to International Monetary Fund (IMF) Special Drawing Rights, and stopping repayments of dollar-denominated Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) debt. We do not explore these potential countermeasures in this study. However, some of the ideas discussed by stakeholders illustrate the range of additional tools that could be brought to bear in a crisis.

III. Sanctions scenarios and their costs

In this section we examine three likely channels of G7 sanctions—on China’s financial system, on certain individuals and entities, and on industrial sectors. We provide an assessment of China-G7 economic value at stake through use of each type of tool, and evaluate implementation challenges, possible effectiveness, and risks.

Economic countermeasures aimed at China’s financial system

In a Taiwan crisis, G7 leaders could consider deploying economic countermeasures targeted at China’s financial system. Financial sector sanctions are a central pillar of the G7’s recent sanctions program aimed at the Kremlin. These measures include actions to block transactions with major Russian banks, freeze their assets, and deny them access to the global dollar payments infrastructure.

This section explores the economic implications of sanctions on China’s financial system, considering two primary options: a targeted sanctions program to limit dollar financing to small banks involved in funding military-related activities, and a comprehensive sanctions program targeting China’s four largest banks and its central bank with the aim of cutting China off from global financial markets.

Global economic links: Finance

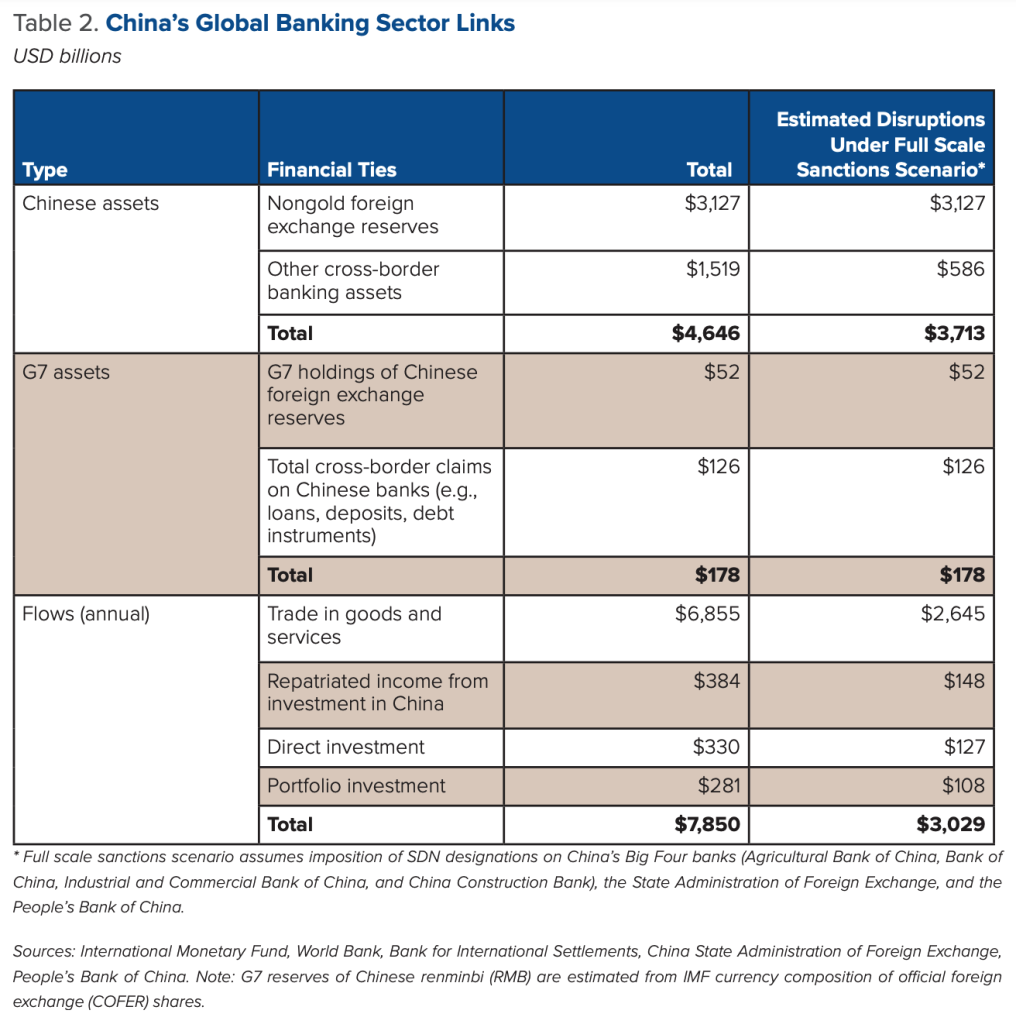

For an economy of its size, China has relatively limited external financial sector ties. China is the world’s second-largest economy and has the largest volume of international goods trade, yet it ranks eighth and ninth in the world in terms of total external assets and liabilities.11 Nonetheless, these ties have critical global importance. As of the end of 2022, China held 95 percent of its $3.3 trillion in reserves in foreign currency (with the remaining held in gold).12 China does not report the exact composition of its foreign exchange reserves, but it is known to hold at least $1.1 trillion in US government bonds through US custodians, and more routed through custodians in Belgium,13 as well as about $300 billion in corporate debt and equity.14 The remainder of China’s foreign currency reserves are held predominantly in euros, Japanese yen, and pounds sterling.15 In addition to China’s official reserves, China’s banking sector holds $1.5 trillion in cross-border assets according to State Administration of Foreign Exchange statistics, most of which is held in G7 currencies.16

Global bank holdings of assets within China’s banking system are much lower. On average, only 3 percent of global central bank reserve holdings are in RMB-denominated assets.17 G7 banks hold $112 billion in claims on Chinese banking institutions such as loans, deposits, and debt instruments, which is only 1 percent of total cross-border bank claims.18 While this means that global banks, on average, are not heavily exposed to China in terms of explicit bank assets, it also means that Chinese banks primarily borrow from Chinese domestic savers and do not depend heavily on foreign borrowing to maintain their balance sheets.

Global exposures to China’s banking system are much greater when considering China’s role facilitating cross-border financial flows, particularly trade. When Chinese importers and exporters do business abroad, they typically do so in foreign currencies: 77 percent of China’s total $6.8 trillion in goods and services trade is settled in currencies other than the RMB, primarily US dollars and euros.19 To facilitate these cross-border payments, Chinese banks maintain correspondent accounts at global banks, which debit or credit dollar and euro payments to the Chinese correspondent accounts on behalf of the foreign customer or supplier. Maintaining these correspondent accounts is a key part of the financial infrastructure underpinning global trade.

Chinese banks also finance other important cross-border flows, including $384 billion in repatriated income from foreign businesses and investments, $330 billion in inbound and outbound direct investment, and $381 billion in cross-border portfolio investment.20

Scenarios

With these financial sector linkages in mind, we consider two potential sanctions scenarios: one in which G7 countries would impose limited sanctions on a small bank with linkages to China’s military or technology sector, and another where they would deploy full-scale sanctions on China’s central bank and China’s Big Four banking institutions.

Limited sanctions scenario

One potential scenario would involve imposing blocking sanctions on a small Chinese bank with limited financial ties to the global financial system and with links to China’s military or dual-use technology sectors. The nominal purpose of these sanctions would be to constrain the flow of foreign financing to military-relevant economic activities.

Actions of this kind have been imposed by the United States before. In 2012, the US Treasury Department sanctioned China’s Bank of Kunlun for providing financial services to six Iranian banks sanctioned by the United States for involvement with Iran’s weapons program and international terrorism.21 In 2017, the United States issued a final rule under Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act severing China’s Bank of Dandong from the international dollar financing system for its role in helping the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) evade sanctions.22

The Bank of Kunlun and Bank of Dandong were relatively small and had limited ties to the global financial system. The financial impact from these actions on the global financial system was minimal. In the case of the Bank of Dandong, for instance, the bank processed $844 million in cross-border transactions in 2016 just prior to being identified as an institution of “primary money laundering concern,” a modest sum in the broader picture of global financial flows.23 While these banks were cut off from the global dollar financing system, they remain connected to the rest of China’s banking sector. As raised in our roundtables, this enables them to continue providing financial services for US sanctioned entities, including Iran and the DPRK.

In a Taiwan crisis scenario, policymakers would face a similar challenge. G7 countries could impose blocking sanctions on small banks, freezing any foreign assets held in G7 jurisdictions and prohibiting domestic individuals and entities from transacting with those banks. However, even if the sanctioned banks lost direct access to correspondent banks in the United States and Europe, they would still have access to financing channels from other Chinese banks, and China’s military-industrial enterprises could still easily access dollar financing, if needed, from other channels in China’s state-run banking system. Rather than make a substantial impact on China’s financing flows, the primary impact of these types of sanctions would be limited to conveying an intent to escalate financial sanctions further, potentially on larger, more systemically important institutions.

Full-scale financial sector sanctions scenario

At the other extreme, the United States and allies could take much more drastic measures against China’s financial system by, for example, imposing blocking sanctions and denying SWIFT access to China’s central bank, its finance ministry, and China’s Big Four banks, which collectively hold one-third of China’s total banking assets.24

The economic impact of such moves would be dramatic, both for China and for the world. This would effectively freeze China’s foreign exchange reserves held in overseas custodial accounts, making them unusable for the defense of China’s currency or to meet short-term obligations to finance China’s imports or external debt repayments. The bulk of overseas assets of the Big Four banks —amounting to around $586 billion—would be frozen.25 This represents a floor, not the ceiling, of the global economic disruption from these actions, which are many magnitudes higher.

G7 assets in China would also be at risk. It is likely that China would freeze the (relatively small) renminbi-denominated holdings of G7 banks. Chinese banks, facing a sudden shortage of foreign exchange due to asset freezes, would likely fall into technical default on G7 bank-issued debt, totaling around $126 billion.

Sanctioned banks would also be cut off from the international dollar payments system. Chinese banks do not systematically report the scale of their cross-border transaction settlements, so we are left to estimate the scale of disruption if China’s Big Four banks were sanctioned. Starting from China’s balance of payments statistics on cross-border trade and investment, we estimate what share of that activity is attributable to the Big Four. We assume that the Big Four banks’ role in facilitating cross-border trade and investment is proportional to their share of foreign asset ownership in China’s whole banking sector, indicating approximately $3 trillion in trade and investment flows could be put at risk, primarily from disruptions to trade settlement. This is only a rough estimate and is likely an undercount, but it illustrates the scale of economic activity at risk from full-scale sanctions on China’s largest banks.

Over the long term, Chinese importers and exporters could move to other, unsanctioned banks for trade settlement and finance, but the immediate disruption to global trade would be substantial and smaller banks would likely struggle to backfill the enormous demand for trade-facilitating financial services in the short term. Eventually, Chinese importers and exporters would adapt to financial-sector sanctions by turning to a different set of banks and potentially engaging in more renminbi-denominated transactions (see Box 1 on China’s international payments alternatives). But the vast majority of China’s exports would be impacted in the short term, as it would be extremely difficult for Chinese companies to receive US dollar- or euro-denominated payments for goods.

$3 trillion in trade and investment flows could be put at risk, primarily from disruptions to trade settlement.

Freezing China’s official foreign exchange assets would also have substantial global spillovers. An asset freeze of China’s dollar reserves would suddenly make dollars in China scarce, driving down the value of the renminbi relative to the dollar. Beijing could fight this depreciation pressure in the short term through strict capital controls and exchange rate interventions, but ultimately would need to allow the renminbi to depreciate to ease outflow pressures and stabilize China’s balance of payments.

A weaker exchange rate would make goods imports more expensive and reduce China’s global economic throw weight. Disruptions to China’s export trade would also entail substantial economic hardship and financial stress for Chinese companies and suppliers to global markets. However, assuming that Chinese exporters and importers eventually found other non-sanctioned banks to legally conduct trade with foreign counterparties, China would still avoid a balance of payments crisis. China presently runs a large current account surplus, providing a consistent flow of dollars into its financial system. In fact, devaluation of the renminbi would ultimately make Chinese exports more competitive relative to other countries, which would push some of the impact of sanctions on to exporters in those countries. Other emerging market currencies, including those of US allies, would be likely to depreciate sharply against the US dollar as well. Countries that depended upon exports to China, such as Angola and Brazil, would see those export markets contract sharply.

The imposition of broad-based financial sanctions on Chinese banks would create significant dislocations within the global financial system and would likely require a coordinated policy response among developed market central banks in order to manage the fallout. Global supply chains would be upended while exporters and importers routed activities to unsanctioned banks. Countries that rely on dollar financing— to finance trade with the United States and Europe, for instance—would face a surge in financing costs, requiring the Federal Reserve to pump dollars back into the global economy through central bank swap lines. But even if swap lines with China were prohibited, these dollars would find their way back into China’s economy due to its trade surplus with the rest of the world.

Takeaways

While it is likely that a financial sanctions package would be on the table in the case of a major Taiwan crisis, avenues for sanctioning China’s financial system face limitations. A lower-scale response that targeted small banks involved with financing military activities would limit the negative impact on the global economy, but it would have little effect on Chinese behavior or military activities because other financing channels would remain open. On the other extreme, a full-scale sanctions response targeting China’s central bank and most of the country’s major commercial banks would have massive economic spillovers—for China’s economy, but also for the global financial system and the global economy. Second-order consequences could include a tightening of global trade financing conditions; weakness in emerging market currencies and balance of payments problems in emerging markets; major supply chain disruptions and interruptions to global manufacturing of consumer goods; and inflationary short-term impacts from interrupted China-world trade.

Sanctions on China’s financial sector could end up falling somewhere between these two extremes, with sanctions placed on midsize banks, for instance. Impacts from these sanctions on trade and financial markets would be more moderate than in the case of a maximal sanctions scenario, but these face many of the same limitations as more comprehensive sanctions.

Fundamentally, the long-term strategic benefit of financial-sector sanctions is unclear. Imposed on small banks, they would have minimal impact on China’s ability to finance military activities. At a large scale, sanctions would disrupt trade with China in the short run, but they would not fundamentally change China’s position within global manufacturing supply chains. Over time, China’s terms of trade would probably improve along with a weaker exchange rate. The symmetrical impact of such sanctions on China and the rest of the world reduces the credibility of such broad-based financial sanctions as a deterrent.

Box 1: How Well-Developed Are China’s International Payments Alternatives?

Over the past five years, China’s Ministry of Finance and the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) have established several platforms to facilitate cross-border transactions and reduce reliance on dollar-based payment systems. Given the increased interest from across the Global South in alternative payment systems to the dollar in the wake of G7 sanctions on Russia, it is likely that in the next five years more of the Chinese systems could be used as a means of sanctions evasion.

In 2015, China launched its Cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) to function as a settlement and clearance mechanism for renminbi transactions. An alternative to the dollar-based Clearing House Interbank Payment System (CHIPS), CIPS is supervised by the PBOC, and participants have the opportunity to message each other through the CIPS messaging system.

Data on CIPS usage suggest that transaction volumes have more than doubled in that period, growing by 113 percent.26 However, while China is making significant progress in developing international payment alternatives, it lags behind the established global payment ecosystem.27 Research indicates that CHIPS has ten times more participants and settles forty times more transactions compared to CIPS.28 These incumbents have well-established networks, widespread acceptance, and trust among global users.

Perhaps the most significant payment alternative is China’s development of its Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), the e-CNY, which began in 2017. The retail CBDC project focuses on enabling individuals and businesses to use the e-CNY for everyday transactions. Interestingly, the PBOC has over 300 staff working on their CBDC project, and only about one hundred working on CIPS.29 However, this retail CBDC project may have limited ability to help internationalize the yuan and facilitate its use as a means of sanctions evasion given its domestic focus and the lack of infrastructure for cross-border use.

The same cannot be said, however, of China’s wholesale CBDC ambitions. China’s wholesale project aims to streamline interbank transactions and improve its cross-border financial system efficiency. Project mBridge is a joint experiment with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Bank of Thailand, Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates, and Bank for International Settlements to create common infrastructure that enables real-time cross-border transactions using CBDCs. In October 2022, the project successfully conducted 164 transactions in collaboration with twenty banks across four countries, settling a total of $22 million, with almost half of all transactions in the e-CNY.

This initiative demonstrates China’s active involvement in exploring innovative solutions for international payments, particularly in the context of cross-border transactions which do not use dollars or euros. This system, though not yet ready for full launch, could help countries bypass dollar-denominated systems like SWIFT or CHIPS and develop an alternative financial architecture.

The biggest challenge for new China-based cross-border payments architecture is liquidity. China maintains capital controls on yuan and offshore clearing, and settlement of yuan is severely limited in comparison to the dollar, euro, pound, and yen. Removing these capital controls to provide liquidity pools for offshore clearing and settlement in yuan will come with some financial instability in Chinese markets, which is undesirable to leadership in the short term.

However, even if certain transactions will be more costly to execute, the recent history of sanctions evasions shows actors are willing to pay a premium to have specific transactions avoid dollars and US enforcement. China is investing significant resources in scaling up these capabilities.

Economic countermeasures aimed at individuals and entities associated with CCP and PLA leadership

Sanctioning the leadership and key associates of adversarial governments, criminal organizations, and terrorist groups is a well-established mechanism deployed by G7 nations and international organizations, including the United Nations. These measures are meant to pressure the targeted individuals, organizations, and governments to change their behavior or policies, while freezing their assets and restricting their ability to raise, use, and move funds.30. In the event of a Taiwan crisis, G7 countries could impose targeted financial sanctions on Chinese government and military officials as well as other politically connected elites to attempt to deter further escalation and increase economic pressure on General Secretary Xi Jinping and his close allies.

Sanctions targeting Russian government and military officials and elites have been a central part of the G7 and allies’ sanctions strategy to counter Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine. Since the 2014 invasion of Crimea, G7 allies have collectively sanctioned more than 9,600 Russian-linked individuals, with a specific focus on government and military officials, oligarchs, and others with links to the regime as well as their family members and close associates who received asset transfers before a sanctions designation.31 As of March 2023, members of the Russian Elites, Proxies and Oligarchs (REPO) Task Force—a coalition of G7 nations, Australia, and the European Commission—have blocked Russian assets valued at more than $58 billion, including both financial accounts and assets such as real estate and luxury goods.32

Separately, some G7 nations have imposed unilateral sanctions on PRC officials in response to human rights abuses and PRC actions in Hong Kong. As of May 2023, the United States had designated forty-two government officials, including former Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Carrie Lam and other PRC government officials, in response to actions undermining Hong Kong’s autonomy.33 In March 2021, the EU also made a rare use of its Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime to sanction four high-ranking Chinese officials for their involvement in human rights abuses against ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, with sanctions including travel bans and asset freezes34—a move complemented by economic countermeasures taken the same day by the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.35

It is highly likely that G7 nations would consider multilateral targeted designations against Chinese government and PLA officials and their associates in a major Taiwan crisis, given their relative success coordinating multilateral sanctions to counter Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.36 The following section explores economic ties at stake and potential sanctions scenarios.

Global economic links: Individuals abroad

Assessing the scale of overseas assets covered by a potential sanctions regime on Chinese government, party, and military officials is extremely complex. There is limited available public information on the wealth of Chinese officials, in large part because that wealth is concealed via layers of personal networks and investment vehicles, and is often managed by third parties. These third parties invest on behalf of officials in domestic and overseas properties, publicly listed companies, and other investments—often in offshore jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands (BVI), the Cayman Islands, and Samoa. These offshore company structures often open bank or brokerage accounts in other jurisdictions, thereby further obscuring the relationship to the ultimate beneficiary.

For the purpose of this study, the authors used data derived from investigative reports and leaks of financial information such as the Panama Papers, which combined give a broad sense of the scale of assets connected to some of the highest-ranking figures of China’s leadership. In 2012, Bloomberg reported that Xi’s extended family held more than $400 million in business holdings and real estate.37 The same year, reporting by the New York Times identified $2.7 billion in assets linked to former Premier Wen Jiabao and his close network.38 Leaks of financial information including the offshore accounts analyzed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in 2014 confirmed the existence of shell companies incorporated in the British Virgin Islands that are linked to the relatives of Wen and Xi, although the value of assets linked to these companies is unknown.39 The leaked information also contained evidence of BVI-incorporated companies held by relatives of former Premier Li Peng and former President Hu Jintao, among others. Despite the opacity surrounding the overseas assets of the elite of the CCP, these single cases are potential indications that relevant, sanctionable assets likely represent tens of billions of dollars in aggregate.

This figure could grow quickly if the targets of financial sanctions were extended beyond high-level CCP and PLA leadership to include politically linked private business leaders. The estimated net worth of the top 200 wealthiest people in China is around $1.8 trillion.40 Twenty-nine of those business leaders are current members of the National People’s Congress (NPC) or the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), with a combined net worth of $278 billion. Much of this net worth is, however, linked to business activities taking place in China, rather than within G7 jurisdictions.

Twenty-nine of those business leaders are current members of the National People’s Congress (NPC) or the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), with a combined net worth of $278 billion

Scenarios

A scenario involving sanctions on Chinese officials could proceed in several stages, with a first set of actions targeting a narrow and lower-level set of party, government, and military officials with direct links to a Taiwan crisis. Further actions could expand these sanctions to close associates of designated individuals, a longer list of officials, or ultimately to a broader set of politically connected business elites. Under the most extreme of scenarios, these sanctions could be widened to include China’s highest-level leaders in response to major developments in the Taiwan Strait.

Sanctions on a narrow set of CCP, government, and military officials

One likely scenario would involve sanctions—asset freezes and travel bans—imposed on a narrow group of CCP, government, and military officials with clear responsibilities over actions taking place in the strait. China’s current minister of defense, Li Shangfu, is already under US sanctions41—but designations could be extended to cover select members of the Central Military Commission or high-ranking PLA commanders. These could also include close advisers to these officials or to China’s high-level leaders on Taiwan-related issues.

The nominal purpose of these sanctions would be largely symbolic, and a means to condemn Beijing’s actions. Their effectiveness in changing behavior is likely to be extremely limited and could contribute to a hardening of positions. Most of this group of designated officials would likely be highly aligned with Xi’s decisions on Taiwan. Narrowly crafted sanctions on officials might also generate limited financial outcomes, given that these individuals are already under tight political scrutiny in China and unlikely to be allowed major overseas holdings. The scope of sanctionable assets might grow marginally larger, however, if close associates and family members are included, especially children of government officials studying in G7 countries, as well as close aides and the third parties handling their investments. Similar to the Russian case, these individuals may become a focus for the G7 if asset transfers occur ahead of designations.

Sanctions on a wider range of CCP, government, and military officials as well as business elites

In response to an escalation in the Taiwan Strait, G7 countries could decide to progressively expand sanctions to cover a longer list of government, CCP, and PLA officials. The list could also include certain business elites with known links to China’s leadership, who lend their public or financial support to China’s actions, or those who are active in sectors linked to China’s military-industrial base. The United States has already designated several Chinese executives and companies for breaking US law by providing support to North Korea, among other violations.42

In addition to asset freezes and travel bans, G7 governments might impose restrictions on professional and financial services provided to these elites, including wealth management or business advisory services.43 While Chinese clients overwhelmingly rely on the expertise of wealth managers based in Hong Kong, a small percentage of other managers are located in Switzerland (1.6 percent), the UK (1.6 percent), and the United States (1.1 percent).44

The purpose of this second round of sanctions would be to attempt to pressure these officials to push internally for a change in policy. Assuming intelligence about their overseas assets were available to G7 implementing authorities, these broader sanctions could end up covering tens of billions of dollars in overseas assets. The costs to designated officials could be high: besides the financial implications of an asset freeze, even the public revelation of foreign assets could be politically damaging.

Our roundtable participants noted that sanctions on individuals amid a Taiwan crisis could potentially produce a stronger response than has occurred with recent designations of Russians. Whereas many Russian officials have been under sanction since 2014 and have had time to adapt, such sanctions on China would be mostly new and immediately impactful to those designated.

Still, it remains unclear whether sanctions on China’s business elites would compel a change in policy. Business leaders arguably have the most to lose from Chinese aggression against Taiwan to begin with, since disruptions in trade and investment with Taiwan and G7 partners will affect businesses first and foremost. The waning influence of the private sector in governance due to crackdowns on the technology and financial sectors under Xi raises further questions about business elites’ ability to influence policy outcomes toward Taiwan.

Sanctions on China’s high-level leaders

In an extreme escalation in the Taiwan Strait, sanctions could end up targeting China’s highest-ranking officials including most members of the Political Bureau of the CCP’s Central Committee and Xi himself. If Russia sanctions are any indication, this third circle of sanctions could also include China’s ministers of foreign affairs, science, and technology or finance, the PBOC governor, or high-level members of China’s legislative bodies (the NPC and CPPCC). These sanctions would similarly be largely symbolic.

Takeaways

The G7’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates that coordinated multilateral financial sanctions on political and business elites are now a central tool in G7 economic statecraft. By design, these sanctions have the benefit of having relatively low immediate economic impacts on G7 economies, concentrating costs on a small number of targeted officials. In principle, these sanctions also have the benefit of avoiding indiscriminately targeting China’s broader populace.45 Though in practice they often end up inadvertently affecting the broader population or the national economy, as foreign banks and private-sector entities reduce exposure to a broader range of individuals or entities than the ones directly sanctioned.

Their effectiveness as deterrence tools in a Taiwan crisis is in question, too. Narrow sanctions on CCP, government, and PLA officials would probably end up targeting political leaders already aligned with Xi’s decisions on Taiwan. Chinese officials may conceal their offshore assets through complex personal networks and corporate structures that are potentially painful and costly to unravel. They also require tight coordination and information sharing among sanctioning parties, in order to locate and act against sanctioned individuals’ assets across jurisdictions. (The foundation for this cooperation does exist, however, as a result of recent sanctions on Russia).

Broader sanctions on business elites could freeze greater overseas wealth, but this may have limited impact on policy outcomes. Private business leaders are already incentivized to disfavor Chinese aggression toward Taiwan and have diminishing political sway after years of power centralization under Xi. Yet because they are an important signaling tool, sanctions on Chinese officials would very likely be considered in a major Taiwan crisis.

Economic countermeasures aimed at China’s industrial sectors

Finally, G7 leaders may consider deploying export controls and other economic statecraft tools against Chinese companies or industries linked to China’s military or defense industrial base.

These actions featured prominently in the G7 sanctions program on Russia, with a variety of trade and investment-related measures imposed on companies and industries linked to mining, electronics, aviation, and other sectors. The United States implemented stronger sector-wide export controls on certain industrial and electrical equipment, added military-linked companies to the US Commerce Department’s (export-control) Entity List, and designated numerous companies on the SDN list.

Currently, Chinese firms with ties to the PLA and specific companies utilizing dual-use technologies already face sanctions and export controls. This signals additional businesses operating in these sectors as likely targets in a Taiwan crisis. In a crisis scenario, a number of economic countermeasures could be used to limit the flow of potential dual-use goods to China’s military and restrict the operation of sectors critical to China’s defense industrial base.

This section describes the economic linkages between potentially targeted sectors and the global economy, as well as the economic assets and flows that could be implicated under an economic statecraft program. To bring more granularity to our analysis, we use a case study approach that explores the potential for restrictions on China’s aerospace sector.

Our findings point to significant economic risks from a broad sanctions package, as well as deep interdependencies between China and G7 economies in potentially targeted sectors. This suggests that, if deployed, countermeasures would likely target narrower industries—or single firms within industries—where China depends on imported G7 technology and where global dependence on Chinese exports is small. Even then, sanctions could come with substantial costs to G7 technology exporters in the sanctioned industries.

Global economic links: Industries and supply chains

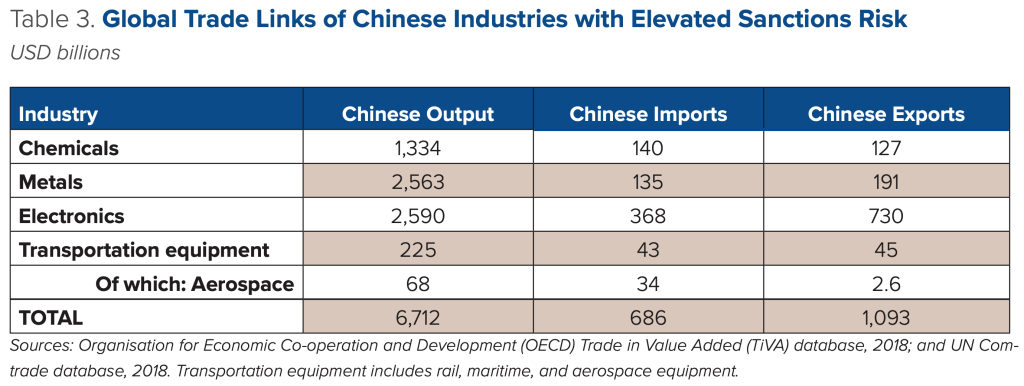

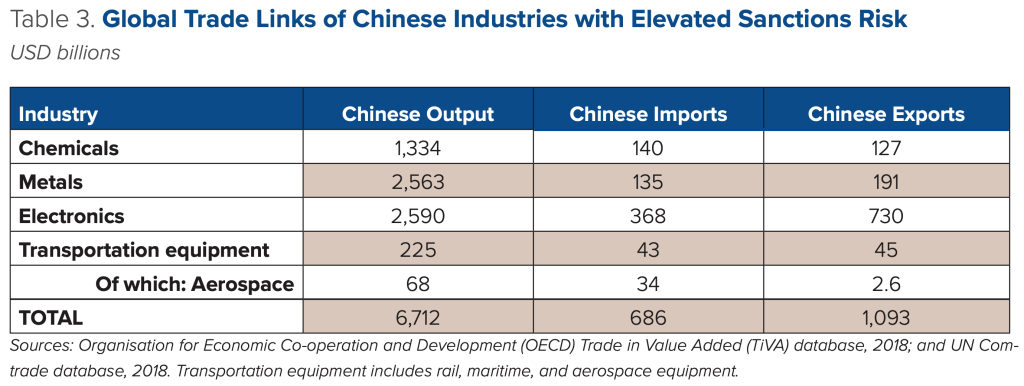

A number of Chinese industries could become the target of G7 countermeasures in the context of a major Taiwan crisis, due to their linkages to China’s defense sectors. Among them, chemicals, metals, electronics, aviation, and shipbuilding already feature prominently in US lists of Chinese military-industrial companies, including the Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies list and the Department of Defense’s Chinese Military Companies list—making them likely potential targets for future action.46

Collectively, these five industries already comprise over ten percent of Chinese gross domestic product, produce over $6.7 trillion in annual revenue, and employ over 45 million people.47 They also are deeply linked to the global economy: in 2018, Chinese companies in these industries imported goods valued at $686 billion, and exported goods valued at nearly $1.1 trillion.

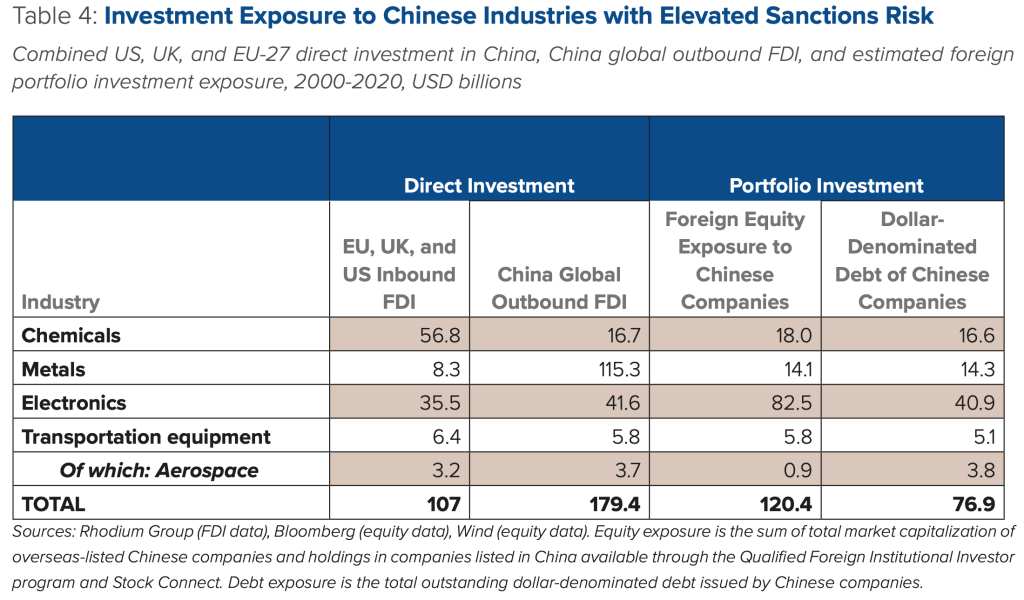

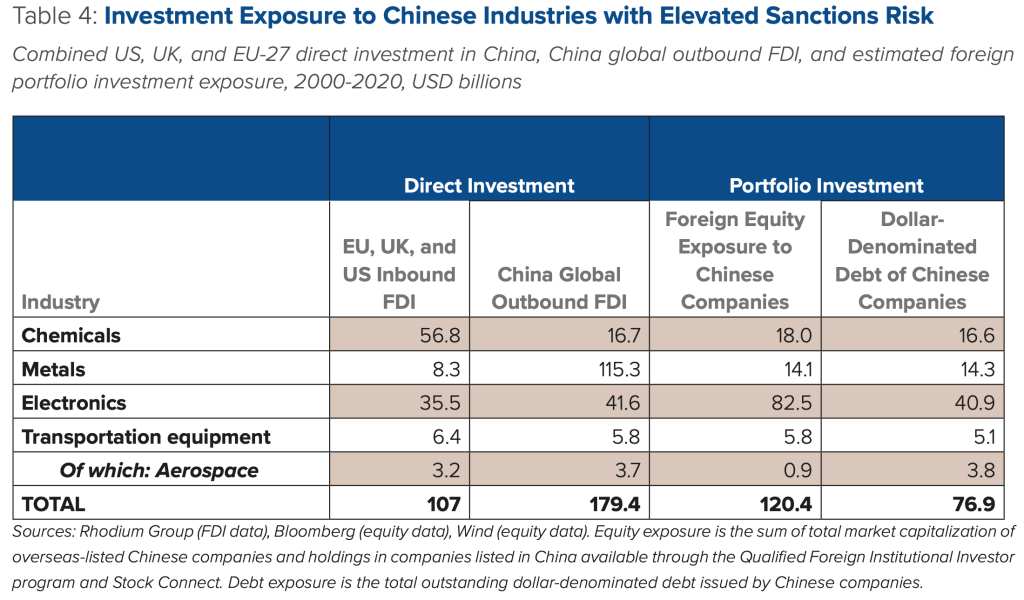

These sectors are also linked to the global economy through investment. Collectively they have been the destination for $107 billion in direct investment from the United States, United Kingdom, and European Union since 2000, and Chinese companies in these sectors have invested at least $179 billion abroad, either through acquisitions or greenfield investment, according to Rhodium cross-border FDI monitoring. Bloomberg data and Chinese official data suggest that foreign holdings of listed Chinese companies and their subsidiaries in these sectors amount to about $120 billion, and these firms have at least $76.9 billion in dollar-denominated debt instruments currently outstanding.48

Scenarios

G7 countries have a range of economic countermeasures that could be brought to bear against select Chinese industries in the event of a Taiwan crisis. Here we consider two potential scenarios, a maximalist export controls scenario targeting major industries with comprehensive export controls, and a targeted sanctions scenario using China’s aerospace industry as a case study.

Maximalist export controls scenario

In an extreme scenario, G7 countries could impose strict export restrictions on trade with China on a range of major industrial sectors, such as chemicals, metals, electronics, and transportation equipment. These sanctions, though highly costly, would not be entirely unprecedented. In the case of Russia, the United States and other G7 countries imposed restrictions on exports in the oil and gas, metals and mining, defense, and technology sectors through a combination of tightened export controls and property blocking rules.

The disruptions to China from such sanctions would be substantial: G7 exporters are the source of 18 percent of the imported content these industries in China consume, totaling $153 billion based on trade in value-added data that estimates the origin and value of production activity along supply chains. G7 countries also account for 43 percent of China’s export market in these industries, putting $225 billion in Chinese manufacturing activity at risk. Altogether, over fifteen million jobs in China are estimated to depend on exports in these sectors. Many more jobs would be put at risk from the loss of imported inputs into Chinese production processes.

These dependencies run both ways, however, and impacts on the sanctioning countries would also be extremely high. The $153 billion in goods that G7 countries export to these industries in China support approximately 1.3 million jobs across the G7; and China itself is the source of 25 percent of G7 imports in these industries.

Even these substantial figures far underestimate the total economic impact from a total ban on trade between G7 economies and these industries in China. The value-added approach provides a useful estimate of the value that different countries contribute to well-functioning global value chains. But disruptions from a sudden stop of trade in these industries—in particular in hard-to-replace critical components—would result in massively greater economic disruption until alternative sources were fully brought up to speed.

Exports from China to the G7 would be disrupted as well. Trade restrictions on foreign inputs to these industries would affect Chinese production and exports. China could also take retaliatory action banning exports from these and other sectors to the G7.

In some cases, alternatives to disrupted trade flows might be found quickly, putting the efficacy of trade restrictions in doubt. A ban on G7 exports of iron ore to China, for instance, would disrupt only a small volume of trade unless other partners such as Australia, which exported $72 billion of iron ore exports in 2022, were also to join. Even so, these supplies could in large part be replaced by exports from other countries such as South Africa and Brazil.49 Additionally, the G7’s challenges in halting the export of high-end Western technology to Russia following its invasion of Ukraine demonstrate that such regimes can be porous.50

The deep interlinkages between Chinese and global industries mean potential economic disruptions from targeting certain sectors could be significant. Altogether, a conservative accounting of the trade flows disrupted by export controls in these sectors amounts to at least $378 billion in disrupted trade.51

Except under extreme circumstances, it is unlikely that G7 leaders would be able to agree to trade restrictions on this scale. Germany, for instance, is deeply invested in and dependent on China in the chemicals industry. The French, UK, and US aviation industries have huge sales to China (see case study below), and Japan and non-G7 members South Korea and Taiwan are deeply connected with mainland China in electronics. These linkages would make agreeing on a broad package extremely difficult. Broad trade restrictions would also be indiscriminate in their impact on China’s citizenry, a fact with serious ethical implications and potentially political ones, as a broadbased export-control regime could in fact strengthen popular support for the government rather than undermine it.52

Finally, a broad export-control package would have major spillovers to the global economy due to global value chains that depend on imports of Chinese intermediate goods (electronics, for instance) that would be disrupted by strict controls. These considerations make measures of this scale highly unlikely, except under the most extreme circumstances.

Targeted sanctions scenario

Due to the costs of a maximalist approach, economic countermeasures against China’s industrial sectors are more likely to be narrower in scope, targeting specific companies or subsectors with high technological dependencies on G7 countries and relatively low global dependency on Chinese exports. The key feature of these countermeasures would be asymmetry: imposing restrictions that disproportionately affect China’s economy. Importantly, asymmetry does not imply costlessness. Any effective trade restriction inevitably results in costs to the sanctioning economy and the global economy as a whole.

China’s aerospace industry, which depends on foreign-sourced engines and parts, provides a case in point. In a potential sanctions scenario, the United States and G7 partners could impose blocking sanctions and export restrictions on China’s two largest aerospace companies, the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) and the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC). These companies depend heavily on inputs from overseas suppliers. Of the eighty-two primary suppliers to China’s first narrow-body jet, the COMAC C919, only fourteen are from China (and seven of those are Chinese-foreign joint ventures).53 China’s most critical vulnerability is engines: all three of its domestically manufactured commercial aircraft rely on foreign-produced engines, and China’s domestic jet engine manufacturers are widely believed to be far behind Western competitors in terms of technological sophistication.54

In a scenario in which blocking sanctions and export restrictions were placed on AVIC and COMAC, all exports of aerospace goods to these firms could be prohibited, amounting to approximately $2.2 billion in aerospace parts trade at risk.55 However, the ultimate impact of such measures on China’s aerospace ambitions would be much greater. China has begun mass production of its ARJ21 regional airliner–which depends on GE engines–and exported its first model to Indonesia last year. COMAC’s flagship C919 narrow-body jet marked its first commercial flight in May 2023, and the country has aspirations to sell over 1,200 over coming years. Restricting the sale of aviation parts to COMAC and AVIC would substantially disrupt China’s civil aviation ambitions.

$33 billion of G7 aerospace exports to China could be disrupted through retaliatory measures.

While the impact of these measures would be particularly acute for China, the costs on foreign aerospace companies would also be substantial. China could respond to restrictions by halting aerospace exports to G7 countries. China exported $1.2 billion in aircraft parts to G7 countries in 2018, including inputs to for eign airliners. While most are low-tech inputs, they can be difficult to replace in the short run: a shortage of wire connectors that coincided with widespread lockdowns in China in 2022 led to US production delays for the Boeing 737.56 China could also respond by delaying purchases of Airbus and Boeing planes. In total, approximately $33 billion of G7 aerospace exports to China could be disrupted through retaliatory measures.

Foreign aerospace companies also have substantial tie-ups with AVIC and COMAC. Since 2000, US and British companies and those based in EU member states have invested an estimated $3.7 billion in China’s aerospace sector, according to Rhodium’s cross-border FDI tracking. A substantial number of these projects are connected to AVIC and COMAC, including Airbus’s A320 final assembly line in Tianjin, which produces six aircraft per month, about 10 percent of Airbus’s average monthly production.57

AVIC and COMAC also have invested in global aerospace companies. AVIC, for instance, acquired Austrian FACC AG, which produces aerostructures and other components for Airbus, Boeing, and other global firms. In a scenario where COMAC and AVIC were put under blocking sanctions, these operations would likely be forced to wind down or divest

Finally, foreign investors would be exposed to losses in equity and debt in AVIC. Foreign equity holdings in twenty-four listed subsidiaries of AVIC companies totaled $1.4 billion, or 1.4 percent of their combined market capitalization as of April 2023.58 Dollar-denominated debt issued by AVIC and subsidiaries amounted to $3.8 billion, approximately 21 percent of its total debt issuance.59

Sanctions on China’s leading aerospace companies and export controls on the components they import would be a heavy blow to its civil aerospace ambitions, making them a plausible economic countermeasure in a Taiwan crisis. However, the impacts on foreign aerospace companies would be significant given the high degree of trade and investment ties to China, making these countermeasures costly and potentially difficult to coordinate in a crisis. Targeted sanctions on other sectors where G7 countries hold asymmetrical technological advantages could also be considered, but these all come with non-negligible costs to the sanctioning economies as well.

Takeaways

China is deeply connected to the global economy in sectors that would potentially be targeted for economic countermeasures in a Taiwan crisis. The expansive nature of these ties would make broad export controls and trade restrictions extremely costly and likely hard to justify except in the most extreme circumstances.

Targeted sanctions on specific firms and technology choke points are more plausible, but they come with substantial costs to foreign companies. Our case study, with export controls placed on China and full blocking sanctions imposed on China’s leading aerospace manufacturers, shows that tens of billions of dollars in aerospace goods trade, inbound and outbound direct investment, and portfolio holdings in China’s aerospace sector would be put at risk. While China would face substantial challenges in achieving its goal of developing a strong domestic commercial aviation industry, foreign aerospace companies would lose out on billions of dollars in exports and sales to China and risk seeing billions of dollars in direct investment lost.

IV. Practical challenges in sanctions development

Beyond identifying specific tools and appropriate targets for economic countermeasures, policymakers will confront a range of complex coordination issues around implementing sanctions in a Taiwan crisis. Discussions with participants in our roundtables highlighted areas of consideration in developing economic countermeasures to deter aggression against Taiwan.

Understanding Taiwan’s perspective. A crucial factor in designing G7 economic responses to possible aggression against Taiwan should be the policy preferences of Taiwan itself. Depending on the nature of the crisis and political conditions in Taiwan, Taiwanese officials might not support economic countermeasures against China and opt for a de-escalatory response. Given the depth of economic ties between China and Taiwan, certain economic countermeasures against China could be highly costly for the Taiwanese economy. Public opinion would likely be divided on the question of how to respond. With only mixed Taiwanese support, G7 coordination on economic countermeasures could be difficult to achieve. Strong Taiwanese support on the other hand would make coordination easier, so long as Taiwanese actions were not seen to have precipitated the crisis.

Defining clear redlines and triggers across the G7. A key barrier to coordinating sanctions among G7 partners and with Taiwan arises from the difficulties in agreeing on what Chinese acts of aggression should trigger economic countermeasures. While some actions might be seen by all parties to have crossed redlines–such as a military quarantine of Taiwan—Chinese coercion against Taiwan often takes the form of “gray zone” measures that are more ambiguous and brush up against but do not clearly cross redlines.60 Getting G7 nations to agree to impose economic countermeasures against China in response to such actions will be more challenging. The roundtables highlighted different levels of tolerance for escalatory action measures among G7 partners.

The specific drivers of a crisis would matter as well: European experts note that a crisis that was seen to be provoked by the United States or Taiwan would make G7 alignment more difficult, especially given divergent views among EU member states about how to respond to a cross-strait crisis.

Coordinated signaling in order to deter. The challenges involved with identifying redlines and agreeing on responses in advance also complicate efforts to signal resolve to China. Successful deterrence depends on the would-be aggressor knowing what actions would provoke a response and believing that the defender’s threats of retaliation are credible.61 The ambiguous nature of Chinese escalatory actions and the potential for disagreements among partners over how to respond in the moment of crisis make establishing deterrence through the threat of economic countermeasures a significant challenge.

Participants in roundtables disagreed about the best signaling approach, with some arguing that clarity about redlines and consequences is essential, and others arguing that providing too much specificity could instead encourage aggressive behavior and focus China’s countersanctions and sanction-proofing work. Providing clarity on what Chinese actions would elicit a punitive response could encourage Beijing to take actions just below such thresholds.

Building out necessary tools. Our roundtables highlighted the fact that G7 countries joining a sanctioning coalition may need additional legal tools to carry out effective countermeasures on China. In the wake of enhanced export controls on Russia, for instance, the EU faced challenges restricting reexports of export-controlled products through third countries to Russia, as doing so would require additional legal authorities.62 And differences in UK, EU, and US regulations have complicated the efforts of multinational companies to wind down their operations in Russia.63 For effective action and deterrence, such authorities would need to be shored up.

Scoping a cost mitigation strategy. Even limited economic countermeasures against China would have global economic spillovers. This means any sanctions program would likely need to be paired with measures to support industries at home as well as third countries affected by lost trade and investment with China. Sanctions triggering a devaluation of the renminbi would negatively affect countries dependent on commodity exports to China. A stronger dollar resulting from global investors seeking liquidity and safe assets in a crisis would put additional stress on countries with substantial dollar-denominated debt. G7 countries would need to manage the global spillovers of sanctions with additional dollar liquidity, loan extensions and forgiveness, and other tools to support the global economy in a period of economic stress.

Factoring in the market reaction. Any G7 economic statecraft response would have to contend with additional disruptions to global supply chains from Chinese aggression against Taiwan and the resulting market impacts. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine caused market gauges like the S&P 500 to fall by around 4 percent, and the initial market impact of a Taiwan crisis could be significantly larger due to the size and importance of the economies involved. US officials have estimated a disruption to the exports of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company alone could cost the global economy between $600 billion to $1 trillion a year.64 Roundtable participants stressed that G7 actions would have to avoid aggressively compounding the inevitable supply chain and market effects of a crisis. The initial shock could undermine domestic political support for sanctions that would incur additional economic costs.

Conclusions and recommendations

Policymakers in G7 capitals are increasingly discussing Taiwan crisis scenarios, and starting to explore the range of options available to them in responding to Chinese actions against Taiwan, both beyond and below the level of invasion. While our work shows that maximalist countermeasures would be highly costly and therefore unlikely except in the most extreme circumstances, G7 countries may consider a set of more limited tools that target areas of asymmetric Chinese dependence on foreign technology and critical inputs.

That options are available, and that G7 leaders are discussing them, does not mean that deploying them in an aligned fashion would be easy. Coordination on economic countermeasures will be critical to effective deterrence, but could be hard to achieve given the difficulty to define red lines in a conflict that is likely to be marked by ambiguity and uncertainty. Given these limitations, economic countermeasures can only be one part of a broader deterrence effort and toolbox that also includes diplomatic and military channels.

From our research, roundtables, and interviews, a set of recommendations emerged for policymakers considering the use of economic countermeasures in a Taiwan crisis:G7 partners and Taiwan should scale up private coordination and signaling. G7 discussions about the role of economic countermeasures in a Taiwan crisis are still in the early stages. Given the challenges involved in agreeing upon red lines and appropriate countermeasures, pragmatic discussions around contingencies must be a priority. This includes creating effective private channels of communication among G7 partners and key stakeholders on emerging trends, financial ties, and shared vulnerabilities. Meanwhile, G7 partners should privately message to China the extent they are willing to go in using economic tools to counter Chinese aggression toward Taiwan. Coordination with Taiwanese officials is also crucial.

The G7 should coordinate beyond its membership. This report assumes that most or all of the current coalition that has imposed sanctions against Russia would align on measures in a Taiwan Strait crisis. Roundtables and consultations with like-minded capitals in the Asia-Pacific region have suggested this is a reasonable assumption. However, even more so than in the case of Russia, exchanges outside the G7, including the rest of the G20, will be necessary given the scale of economic disruption at stake.

Economic asymmetries need to be better understood. Policymakers argued that the most likely economic countermeasures would focus on areas where China is asymmetrically dependent on foreign goods, technology, and finance. Further research is needed to identify these areas and the potential costs, vulnerabilities, and limitations of targeting them in a crisis.

Take practical legal steps now to boost the credibility of G7 deterrence. Discussants noted that successful deterrence requires making clear that G7 nations are ready to act decisively in a crisis. This may require legal steps, including: shoring up of the EU’s framework for export controls; advance preparation of US executive orders specifying and granting sanctions authorities to the Office of Foreign Assets Control; preliminary analysis on the potential impact and spillovers of proposed packages; and the construction of communication channels among US government stakeholders such as the Federal Reserve, Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, and appropriate bilateral, plurilateral, and multilateral counterparts. This may include preparing the legal and regulatory landscape across G7 jurisdictions to ensure appropriate authorities are in place to deter or respond to a crisis.

Invest in other forms of deterrence. Economic countermeasures should be considered as part of a whole-of-government and multilateral strategy as they have costs and limitations that can make them less effective on their own. These tools will be more effective when paired with traditional tools of deterrence in both the military and diplomatic realms.

Keep lines of communication open. Bilateral and plurilateral communication is the best tool to de-escalate in a crisis. Recent breakdowns in military-to-military communication channels between the United States and China are of serious concern given elevated tensions in the region. Maintaining open communication lines and regular exchanges with Chinese counterparts is a key element in any risk-mitigation strategy.

Balance credible threats with credible assurances. Effective deterrence requires credible threats to be matched with credible assurances. The G7 should make clear to Beijing it has no desire to change the status quo in the Taiwan Strait. Efforts to maintain the status quo and shore up traditional diplomatic, military, and economic tools to ensure peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait should be the priority.

No comments:

Post a Comment