Brahma Chellaney

India recently overtook China in population size, and although its economy remains smaller, it is growing faster. Indeed, India is now the world’s fastest-growing major economy—its GDP has already surpassed that of the United Kingdom and is on track to overtake that of Germany. India thus represents a major export market for the US, including for weapons.

But commercial opportunities are just the beginning. In an era of sharpening geopolitical competition, the US is seeking partners to help it counter the growing influence—and assertiveness—of China (and its increasingly close ally Russia). India is an obvious partner for its fellow democracies in the West, though what it really represents is a critical ‘swing state’ in the struggle to shape the future of the Indo-Pacific and the world order more broadly. The US cannot afford for it to swing towards the emerging Russia–China alliance.

Consider America’s quest to bolster supply-chain resilience through so-called friend-shoring. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has explained, India is among the ‘trusted trading partners’ with which the US is ‘proactively deepening economic integration’ as it attempts to diversify its trade ‘away from countries that present geopolitical and security risks’ to its supply chain.

India is also integral to maintaining peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific. Its military standoff with China—now entering its 38th month—is a case in point. By refusing to back down, India is openly challenging Chinese expansionism, while making it more difficult for China to make a move on Taiwan. Biden hasn’t commented on the confrontation, but he is certainly paying attention. It’s telling that both Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan visited New Delhi this month.

Already, India holds more military exercises with the US than any other power, and as of 2020, it had signed all four of the ‘foundational’ agreements that the US maintains with all its allies. This means that the two countries, among other things, provide reciprocal access to each other’s military facilities and share geospatial data from airborne and satellite sensors. Meanwhile, India’s involvement in the Quad—along with the US, Australia and Japan—has lent the grouping much-needed strategic heft.

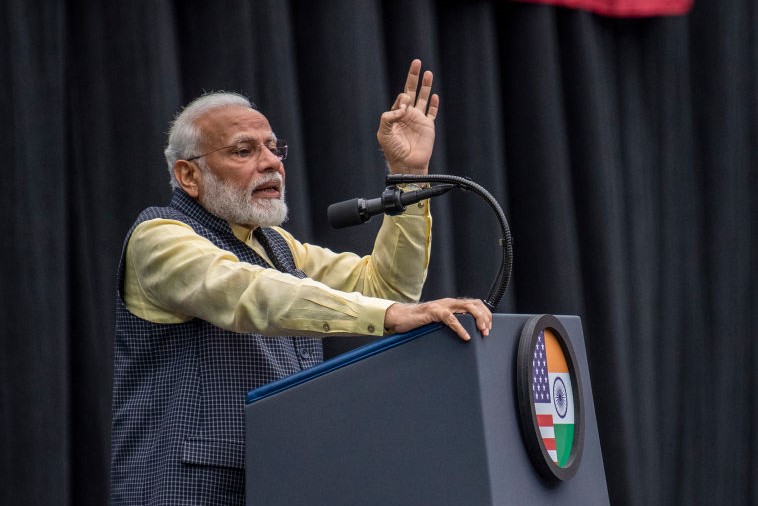

Fortifying the strategic relationship with India is one of the rare issues eliciting bipartisan consensus in the US. The latest invitation to Modi to address the US Congress—he is the first Indian leader to do so twice—came from Democratic and Republican leaders alike.

Nonetheless, plenty of sceptics in the West believe that US efforts to cement strategic ties with India will disappoint. For example, one commentator recently declared that India will never be an ally of the US, and another argued that treating India as a key partner won’t help the US in its geopolitical competition with China.

A key concern is India’s commitment to retaining its strategic independence. While India has rarely mentioned non-alignment since Modi came to power, in practice, it has been multi-aligned. As it has deepened its partnerships with democratic powers, it has also maintained its traditionally close relationship with Russia.

But India’s relationships with the US and Russia seem to be moving in opposite directions. India is building a broad and multifaceted partnership with the US—covering everything from cooperation on human spaceflight to the construction of resilient semiconductor supply chains—whereas its relationship with Russia now seems limited almost exclusively to defence and energy.

Nonetheless, India isn’t prepared to shun Russia, as the West has since the invasion of Ukraine, not least because India still views Russia as a valuable counterweight to China. In India’s view, China and Russia are not natural allies at all, but natural competitors that have been forced together by US policy. A Sino-Russian strategic axis serves neither India’s nor America’s interests, yet, much to India’s frustration, the US appears to have little interest in rethinking its policy.

This isn’t the only area where India believes that US policy undermines Indian security interests. India also takes issue with America’s insistence on maintaining severe sanctions on Myanmar and Iran, while coddling Pakistan, where mass arrests, disappearances and torture have become the norm. The US is now threatening visa sanctions against officials of Bangladesh’s secular government—which is locked in a battle against Islamist forces—if it believes they are undermining elections that are due early next year.

The US is not accustomed to being challenged by its partners. Its traditional, Cold War–style alliances position the US as the ‘hub’ and its allies as the ‘spokes’. But that will never work with India. As the White House’s Asia policy tzar, Kurt Campbell, has acknowledged, ‘India has a unique strategic character’ and ‘a desire to be an independent, powerful state’. Far from a US client, India ‘will be another great power’.

Campbell is right. But that doesn’t mean that the sceptics are also right. While a traditional treaty-based alliance with India wouldn’t work, the kind of soft alliance the US is pursuing, which requires no pact but does include, as Campbell also underlined, ‘people-to-people ties’ and cooperation on ‘technology and the like’, can benefit both sides.

The US and India are united by shared strategic interests, not least in maintaining a rules-based Indo-Pacific free of coercion. As long as China remains on its current course, so will the Indo-American relationship.

No comments:

Post a Comment