Darin Gaub

I continue to revisit many of the topics on which I instructed during my time as a leader and trainer in the U.S. Army. I was also able to apply what I taught in a classroom or training environment in the real world on numerous occasions and prove through experience what worked and what did not. Though I have been retired for four years now, my work as an executive coach and in the non-profit universe has me going back to my active-duty time and continuing to coach on some of the same topics. One of those topics is to show the difference between Measures of Performance and Measures of Effectiveness.

As you see the road stretch out in front of you, flat, smooth, and void of all traffic, you decide to push your Ford Mustang to the limit. You reach 150 miles per hour, and it still feels like you are only going sixty. You decide that this is fast enough and as you slow down you become aware of the sirens intruding on your peace and quiet. You pull over and come to a full stop fully aware of the fact that this could result in more than just a ticket. The Highway Patrol Officer is not impressed with the fact that your car performs so well, she is only concerned about your breaking the law.

Just because your car is capable of certain measures of performance (tuned, timed, powerful, good tires) does not mean you were effective and did things right (acted safely, followed the law, exercised good judgment).

There are many simple lessons we can apply if we ask ourselves and our organizations if we are measuring performance or effectiveness in what we do.

The first time I saw a large group recognize the difference between these two measures was when training U.S. Army Combat Brigades at the National Training Center in Fort Irwin, California. One of the many “hats” I wore was as a trainer and coach for Unmanned Aerial Systems, or drones. Whether it is a Global Hawk that flies between continents or a quadcopter that flies between hill tops the lesson is the same. Measuring how many times you safely launch and recover the aircraft, and the number of hours flown is a simple measure of performance.

You are doing things right.

What you are not measuring is whether you are effective. Launching and recovering aircraft and flying for hours on end is not the critical measurement, what matters is if the time and energy spent doing those things makes a difference.

Did you do the right things?

Did you identify a critical enemy encampment, or spot an insurgent emplacing an explosive device at a known location and call that in for a swift response? Were you able to relay communications between military units? Were you able to find the enemy command and control center? The process of answering the question of effectiveness is a lot harder, which is why few organizations take the steps necessary to reach the next level of analysis.

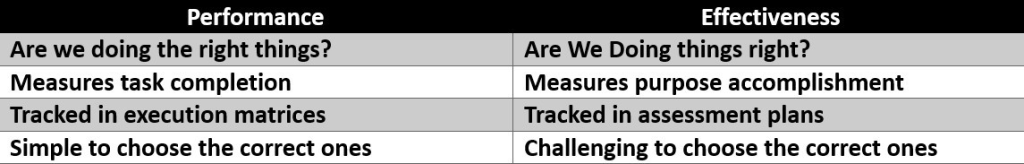

This chart shows a simple side-by-side comparison of the two measures. To put it in the context of the use of drones, measuring performance requires simpler analysis at a smaller level of the organization. In the Army, this would be a platoon of about thirty people. The measure of real effectiveness requires a cross-functional look at a higher level involving many parts of the organization. In this case a Brigade of thousands of people and multiple staff sections. This is hard work.

When looking at a political non-profit there is often a temptation to use social media posts or followers, or an email list to determine whether your organization is effective. One of the reasons why is the assumption that having millions of emails, thousands of followers, or routine social media activity means you can fundraise effectively. It may be true that an organization that is loud on social media gets the money, but that does not mean the organization is effective.

Political non-profits know that donors are their lifeblood, so they tend to focus on what it takes to show donors how they are performing. One way to do this is to show simple social media statistics or your email list. Unfortunately, this is only an easy measure of performance, not a measure of the organization’s effectiveness. Who can blame an organization for taking the easier route when a simple surface-level performance analysis reaches the donors who often do not have time to find out if you are effective?

Here is a real-world example. In my organization, Restore Liberty, we tested a Constitutional Sanctuary Declaration at the county level in one of the states where we have a director. We did not blast that work in social media or to multiple emails. We do not know if all who follow us on social media and read our occasional updates are friends or foes, or even real, so we just do the work.

In the process of testifying to the County Board of Supervisors our State Director and Deputy Director educated the board on the U.S. Constitution. They also exposed a County Attorney for his role in selling off land and commodities to China directly or through proxies and managed to gain the attention of some of their statewide elected officials who began to look deeper into the problem. Selling land to foreign adversaries in the state is illegal. We were in pursuit of a constitutional sanctuary declaration that was not ultimately signed, but we were still effective. If we had made what we were doing public we might have been able to show our ability to perform, but we would rather be effective, even if in ways we did not anticipate.

If you run a political non-profit organization, avoid the temptation to simply add to the volume of social media posts that tend to magnify the problems and instead do the harder work of identifying ways to solve problems. In Restore Liberty our chief solution is the successful pursuit of a Constitutional Sanctuary State or County resolution. A resolution with real teeth.

No comments:

Post a Comment