SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

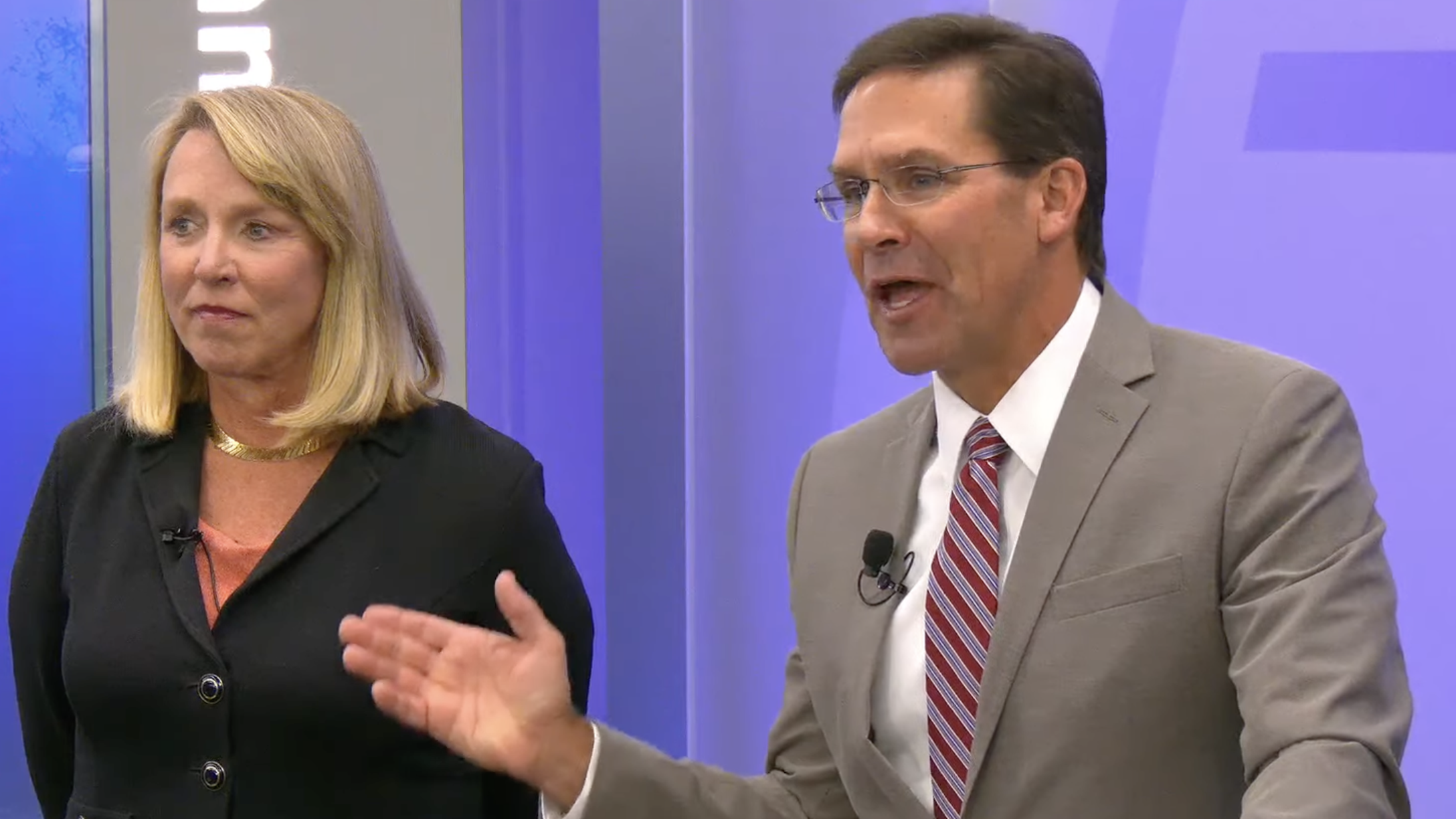

WASHINGTON — To fix the Pentagon, start in Congress. That’s the central takeaway from an Atlantic Council commission co-chaired by Mark Esper, former Secretary of Defense, and Deborah Lee James, former Secretary of the Air Force.

The commission’s interim report, released today, argues that before the Defense Department can adopt new technology at the speed and scale required to compete with China, legislators must loosen statutory limits in an array of areas, from reprogramming funds between projects mid-year to contracting with start-up companies. It also calls for Congress to accept less detailed budget data in the Pentagon’s annual requests.

In return, the Hill would get a new digital “dashboard” that lets staffers directly access the latest program information from the Pentagon’s Advana acquisition analytics, without waiting for defense officials to process a formal request for updates.

The report also urges internal reforms that DoD can do itself, such as bypassing and streamlining the notoriously bureaucratic JCIDS process, which generates many of the official requirements needed to launch new weapons programs. (James noted today that one of these recommendations, strengthening the Defense Innovation Unit, was already executed by DoD last week). But of the ten broad recommendations made in the report, nine require at least some action on the Hill.

“The United States is the global leader when it comes to innovation,” Esper declared at the report’s roll-out this afternoon. “We are the envy of the world. We do not have an innovation problem in this country. However, the Pentagon’s ability to quickly adopt this advanced technology is woefully inadequate. That is where the problem resides.”

“The United States of America does not does not have an innovation problem,” echoed Lee. “But we do have, within the Department of Defense, an innovation adoption problem.

That the Pentagon struggles to get key tech out of the prototype or pilot-project stage, across the bureaucratic so-called valley of death, and into large-scale manufacture and deployment is a common diagnosis. But some of the report’s prescriptions are far from obvious, including ones that don’t directly involve the Defense Department.

For instance, the report wants Congress to reform the Small Business Administration’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants program, which the DoD often uses but does not run. Currently, SBIR doesn’t allow small companies to apply if they’re publicly traded or more than 50 percent funded by venture capital. But, the report argues, those two conditions exclude a large number of R&D startups, especially in software, because such companies are hungry for capital to hire skilled engineers or buy exotic equipment. “By disallowing them from competing for SBIR grants, the DoD is limiting technology competition among some of the most technology-proficient corners of the industrial base,” the authors write.

The bulk of the report’s recommendations, however, focus on the ponderous budgeting and programming process, much of which is driven by Congress. In their introduction, Esper and James highlight a proposed pilot project that would give five Program Executive Officers more authority to shift funding among the multiple procurement programs each PEO oversees. That would require congressional approval.

The report also asks Congress to okay a major consolidation of smaller projects that today have their own Budget Line Items and Program Elements in the budget — there are currently over 1,700 BLIs and PEs — to, again, allow defense officials more freedom to move funds between them. It also asks the Hill to restore the old rules for reprogramming money from one line item to another, which only required DoD to notify Congress after the fact, with Congress having a 30-day window to move the money back, rather than the current system under which DoD must ask for permission beforehand. Both changes would make it easier and quicker to move money from failing or stalled projects to others with more potential or more urgent needs.

It’s worth noting that while Esper and James wrote the introduction to the report, they didn’t write the body, and they don’t necessarily endorse every item. To that end, a small-print disclaimer notes that “the analysis and recommendations presented in this Interim Report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of … [the] Commissioners.”

Those authors are Whitney McNamara, a think tanker and former DoD official turned consultant; Peter Modigliani, a software acquisition expert at MITRE; and Eric Lofgren, who worked for the commission while a research fellow at George Mason but who has since joined the staff of the Senate Armed Services Committee — which puts him in prime position to nudge Congress towards what will likely be controversial reforms.

No comments:

Post a Comment