Ori Sela

Relations between Beijing and Taipei are increasingly strained, and with the war in Ukraine in the background, some claim that “Taiwan is China’s next step.” How is “threat diplomacy” expressed vis-à-vis the contested island; how does the struggle between China and the US influence the issue of Taiwan; and how should Israel act in the face of developments?

Over the past decade, China has stepped up its “threat diplomacy” toward Taiwan, including military signals by air and sea, and even missile launches close to Taiwan; economic threats, including sanctions, tariffs, blockades on exports/ imports; cyber and cognitive attacks, and constant efforts to reduce global recognition of Taiwan. In addition to these threats, economic enticements are offered to those who follow China’s lead. The “threat diplomacy” intensified as Taiwan enhanced its relations with the United States, which strengthened its support for and commitment to Taiwan through legislation, economic agreements, arms deals, and mutual senior official visits; all while tensions between the United States and China have grown in recent years. While it is claimed that China is acting in this way because of its growing self-confidence and greater military power, the “threat diplomacy” also is the result of what China perceives as a threat: that Taiwan distances itself from the vision of unification with China. For Israel, the right course is to continue developing a wide range of unofficial contacts with Taiwan, while also continuing to foster its relations with China. However, as tensions between China and the United States become exacerbated over Taiwan, Israel’s room to maneuver could become limited, with the United States expecting Israel to stand unambiguously by its side.

Over the past decade, China has intensified its “threat diplomacy” toward Taiwan, including military signals by air and sea, and even launching missiles close to Taiwan; economic threats, including sanctions, tariffs, blockades on exports/imports; cyber and cognitive attacks; and constant efforts to reduce global recognition of Taiwan. Beyond these threats, economic enticements are offered to those who follow China’s lead. The “threat diplomacy” actually grew stronger just as China and Taiwan had strengthened their relations through trade, mutual investment, visits, tourism, and more, and especially as Taiwan intensified its relations with the United States, which increased its commitment to Taiwan through legislation, economic agreements, arms deals, and mutual senior official visits; all while tensions between the United States and China had intensified in recent years. Many commentators have claimed that China is acting this way because of its growing self-confidence, perhaps over-confidence, and as a result of its considerable military buildup; yet the “threat diplomacy” also stems from what the Chinese perceive as a threat: Taiwan’s moving further away from the vision of unification with China – a core element in China’s ideology, certainly under its president for over a decade, Xi Jinping – and developing into an “threshold-independent state.”

Background

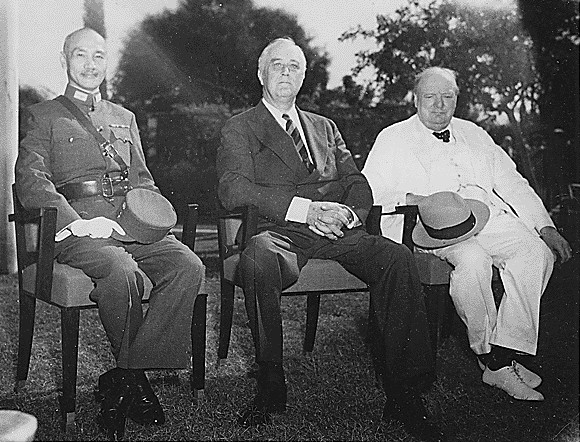

At the Cairo Conference in 1943, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek (the leader of the Republic of China – ROC) drew up principles for the world order after the end of World War II. It was agreed that Taiwan was part of China and that it should be returned to China from the Japanese, who had controlled the island for five decades. The two powers that were competing for control of China – the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) led by Mao Zedong and the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) led by Chiang Kai-shek – accepted this principle, and soon thereafter, the policy of both parties remained consistent: Taiwan had been and should be an integral part of China. On October 1, 1949, at the end of a bloody civil war between the two, Mao declared the establishment of the PRC – People’s Republic of China – after the CCP managed to drive the Kuomintang from mainland China. The Kuomintang retreated to Taiwan and a few other small islands, where they continued to maintain the “Republic of China,” while China and Taiwan saw each other as a kind of “rebellious region,” and union between the two – each on its own behalf – as a national aspiration.

Over the following decade, China tried to bring about a union by force. However, a series of military crises, particularly in 1955–1956 and 1958 (the first and second “Taiwan crises”) when the United States intervened in Taiwan’s favor (in addition to American legislation that expressed its commitment to defending the island), made it clear to China that military recourse was blocked. Taiwan also understood the limits of American support, and that the United States would not back any Taiwanese invasion of the mainland.

So the low-level friction (sporadic shelling, for example) continued until the end of the 1960s accompanied by mutual propaganda aimed at persuading the neighboring country’s citizens to revolt. The turning point came in the early 1970s with the beginning of the normalization process between China and the United States. Already in the initial declarations by the countries’ leaders in 1972, when President Nixon visited Beijing, the Taiwan issue was central. Even before the meeting, in 1971, the issue of Taiwan and the removal of the ROC from the UN – of which the ROC was a founding member and one of the five permanent members of the Security Council, representing “China” – in favor of the PRC, the new sole representative of China in the UN since then, showed the way the wind was blowing. In 1979, China and the United States instituted diplomatic relations and the subject became clear: the United States recognized the “One China” principle, and the PRC was recognized as the official representative of this One China, while the United States added a series of declarations and laws relating to the defense of Taiwan and to guiding the union between China and Taiwan in solely a peaceful way.

Between the Third Taiwan Crisis and Improved Relations

The normalization between the United States and China allowed China and Taiwan to enter into secret discussions, which gradually matured into the “1992 consensus,” in which the One China principle of was agreed, along with the understanding that the implementation of this principle would take place gradually, with dialogue, and over time. However, as the United States and Taiwan intensified contacts between them – the Taiwanese president’s visit to the United States in mid-1995 became the symbol of this intensity – China interpreted this as a threat to the One China principle, and tensions resumed. In Taiwan, the democratization process was then at its height, with the general elections at the end of 1995 and the first direct presidential election in early 1996, and the question of Taiwan’s “independence” was at the forefront. Consequently, the tension mounted and China conducted military exercises around Taiwan, which included live artillery and rocket fire as well as the launching of ballistic missiles: the “third Taiwan crisis” (1995-1996). Once again the United States intervened, and when two American aircraft carrier battle groups arrived in the region, the crisis ended with China understanding the limitations of its power.

The feeling in Beijing was that there was “no partner” on the other side, and when the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) came to power in Taiwan in 2000, talking openly of “independence,” the rift continued. However, from about 2004 onwards, China permitted more informal contacts with Taiwan (including economic contacts and the ability to travel between China and Taiwan), and began to nurture ties with the Kuomintang, which was then in the opposition. Indeed, in 2008 when the government changed and President Ma Ying-jeou – a member of the Kuomintang – took office, contacts between Taiwan and China improved. Ma supported this bettering of ties under the triple principle of “without union, without independence, without the use of force,” or in other words, maintaining the political situation while promoting other ties. Mutual trade and investment rose, tourism increased, and tens of thousands of Chinese citizens settled in Taiwan, and vice versa. Although China did protest agreements on US arms sales to Taiwan and against American attempts to have greater involvement in East Asia, it did so without damaging the strength of its contacts. At the same time, many in Taiwan felt that stronger ties with Beijing were at their expense and that they were a sign of Taiwan’s growing dependence on China. Extensive protests broke out, and Tsai Ing-wen, the DPP candidate, won the 2016 presidential elections.

The Threat Diplomacy and the Fourth Taiwan Crisis

Tsai’s explicit statements on the issue of independence, together with an unprecedented phone call with President Trump after his election, added fuel to the flames, while the Chinese president, who was nearing the end of his first term, in return, amplified his rhetoric. The deterioration of relations between China and the United States, and the increase in arms deals between the United States and Taiwan, together with China’s generally aggressive diplomatic approach and growing military signals, added to the tension. As the rift between Beijing and Taipei was renewed, China began to feel threatened by one of its foremost strategic concerns: with American help, Taiwan had turned itself into a “threshold-independent state,” and China adopted the “threat diplomacy.”

In September 2020, when the American undersecretary of state visited Taiwan (after the United States announced it was supplying F-16 fighter aircraft to the island), China intensified its response. Sending planes into Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) became routine, with the Chinese Air Force setting a precedent of crossing the “Median Line” (which also gradually became routine). This trend continued after Joe Biden became US president. American diplomatic activity intensified, by creating and expanding economic and military agreements in the Indo-Pacific. The “chip war” began, and the array of new agreements between the United States and Taiwan became, as China saw it, a concrete threat. The war in Ukraine brought Taiwan into the headlines (“China’s next step”), and the tone became harsher. In August 2022, the visit to Taiwan of Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the US House of Representatives prompted the start of the “fourth Taiwan crisis,” and as soon as she left, China embarked on a de-facto siege of the island by engaging in a series of military exercises around Taiwan, including live artillery and rocket fire and the launching of ballistic missiles, as well as maneuvers by the Chinese Air Force and Navy. Remarks by President Biden that breached the policy of ambiguity regarding the US protection of Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion (although minimized by American spokespeople), caused tempers to flare in China as did the US “legislative inflation” on strengthening cooperation with Taiwan.

On March 29, 2023 Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen landed in New York – for the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was her seventh visit to the United States as the president of Taiwan. As usual, the visit was described as a “stopover,” and not an official visit, while on route to Central America. China strongly objected to the visit, especially President Tsai’s meeting with Speaker of the US House of Representatives Kevin McCarthy during her “stopover” upon her return to Taiwan. While the United States downplayed the importance of the meeting, China saw it as another insult and again significantly increased the frequency of its aircraft infiltration of Taiwan’s ADIZ, along with extensive training and exercises around Taiwan, in what has been referred to as “the new status quo.” These exercises included dozens of aircraft infiltrations that crossed the Median Line, while operating a Chinese aircraft carrier east of Taiwan, along with increased use of drones.

Conclusion

China sees the Taiwan issue as purely a domestic matter and a core national interest that threatens its unity and sovereignty, serving as a precedent for destructive separatism (and for effective Chinese democracy) and an unfinished chapter in its civil war that undermines the legitimacy of the CCP. Therefore, the (“renewed”) union of Taiwan with China is seen as an essential component in achieving “the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation” – the vision of the party leader Xi Jinping since the outset of his presidency.

Visits by senior US officials to the island and meetings in the United States, arms sales, and many recent economic and technological agreements are, as far as China is concerned, all indicative of a de-facto American withdrawal from the “One China” principle. Moreover, China sees it as part of a growing attempt by the United States and its allies to “contain” China in the Asian space and even foil its efforts at internal development. Consequently, China’s hope to end the Taiwanese issue by peaceful means – Beijing’s strategic preference – is fading. Declarations by the United States that it has not changed its policy sound empty to Beijing, and as tensions rise between China and the United States, even unrelated to Taiwan, and the dialogue between them becomes curtailed – particularly on military matters – the chances of an unplanned or unwanted clash increase, and for China a military clash is undesirable. It is important to remember that increasing tensions over Taiwan, both in the United States and China, often occur due to internal political considerations and not from any significant strategy or planning, and this has implications for the random nature of fueling the flames and the unexpected over-reactions. This was the case in August 2022, when the United States was facing midterm elections and China was preparing for the Congress where Xi would be elected for third term as general secretary.

And what about Israel? Israel’s policy in this context is conducted in the shadow of its US–China relations and based on accepted principles: Israel recognizes the “One China” principle and has diplomatic and extensive economic relations with China, alongside economic and cultural relations with Taiwan. Israel must continue to act cautiously between the powers, taking into account their sensitivities on the subject of Taiwan. It would be correct to continue developing a variety of unofficial contacts in Taiwan, between peoples, organizations, and individuals – as China is doing – to encourage trade, academic contacts, business and civic ties, while promoting formal relations with China. As in the past, should relations deteriorate between the powers over the issue of Taiwan – and in other contexts as well – Israel’s room to maneuver between them will become limited, while the United States will expect Israel to stand unambiguously by the side of its greatest ally, certainly in any extreme scenario.

No comments:

Post a Comment