Mackenzie Eaglen

With the passage of Congress’ debt ceiling agreement, defense spending seems to be locked in at President Biden’s proposed $886 billion for fiscal year 2024.

While the highest nominal defense budget in history, when taken as a portion of gross domestic product (GDP), this budget will be among the slimmest for the Pentagon since before World War II. When accounting for inflation and other must-pay bills, this military’s budget is declining by three percent.

Despite this concerning statistic, the American public is too often put at ease in believing that the US military remains far ahead of any of its competitors since US spending on defense dwarfs the next ten countries combined.

However, cracks and strains are evident across the armed forces as inflation is cutting into the Pentagon’s buying power and further reducing the little share left to decision makers to fund new equipment, technology, concepts, and posture.

When contrasted with potential adversaries, such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which has near-term military ambitions heavily weighted in their own neighborhood, the strain on the Pentagon’s budget becomes more apparent. For the US to properly compete on the other side of the globe requires significant power projection capabilities that are costly. As a global power, the United States must also simultaneously balance other priorities, such as deterring Iran, countering Russian aggression, and shoring up allied commitments. As a three-theater force, buying power is further diluted as choices must be made where to allocate different forces, and the total US defense budget is spread more thinly through multiple theaters.

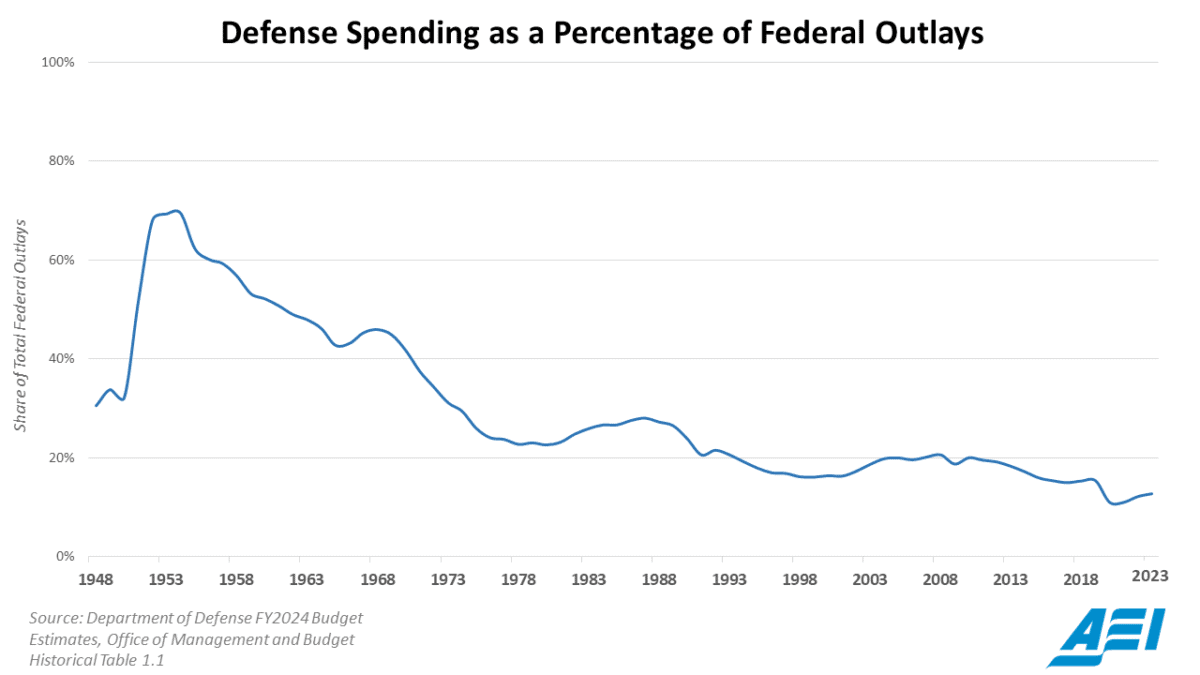

American defense spending has not been growing proportionally with the nation’s wealth nor other federal spending. Our military budget continues to shrink as a percentage of national GDP, with the spending levels for defense projected in Fiscal Year 2025 likely taking the budget under three percent of GDP for the first time since the days of the peace dividend. With US GDP growth averaging around three to five percent, the defense budget should similar boosted. However, recent defense budgets haven’t even managed to keep pace with inflation, subtly chipping away at our combat power. Furthermore, military spending continues to decline as a proportion of the federal budget since the end of the Cold War, making up just ten percent of federal expenditures as of 2022, the lowest level since World War II.

Meanwhile, the Chinese Communist Party is wasting no time in consistently increasing military spending. At the opening of the 14th National People’s Congress this past March, Beijing announced a defense budget of $227.79 billion (1.55 trillion yuan), a 7.7 percent increase from the previous year following a decade of similar substantial hikes.

Even with these large increases in China’s defense budgets, these self-reported figures still do not paint the whole picture.

China’s real military budget is far bigger. Just last week Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK), revealed on the floor of the Senate that “They [intelligence officials] came out and said the real Chinese budget, in terms of military, is probably close to about $700 billion dollars.” This far more competitive figure is equivalent to roughly 4 percent of the PRC’s GDP.

Furthermore, Chinese party leader provided data lacks considerable transparency and official disclosures are narrow in detail, only categorizing spending across three simple categories: personnel, training and maintenance, and equipment.

Getting a clear bottom line estimate is further complicated by the PRC’s policy of military-civil fusion, where increasingly blurred lines with commercial enterprise and dual-purpose investments make it unclear where a dollar spent for civilian purpose ends and a dollar spent for military purpose begins.

Simply converting spending in Chinese yuan to US dollars based on a currency exchange rate overstates American capacity if China pays significantly less for most things. Vacationers know as good as anyone that a dollar spent in one place can go a lot further in others. For this reason, economies are often measured on Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in order to conduct relevant comparisons—and this is why China has the world’s largest economy when using accounting for PPP. The principle holds when paying soldiers or purchasing military hardware.

One economist determined that the US-China military spending gap narrows even further when considering purchasing power specifically within the defense sector. As my AEI colleague Bill Greenwalt has written, when accounting for PPP and extraneous nondefense spending hidden within the defense budget, it’s possible that China is outspending the US in real terms.

Other structural factors, such as a lower standard of living in the PRC, allow Beijing to allocate its military spending differently. For example, when it comes to military pay, the United States does better job of taking care of its servicemembers. An entry level soldier in the PLA earns only $108 a month, roughly sixteen times less than the $1,900 of their American counterpart. Where Beijing saves on compensation, it can make up for in ships, planes, missiles and other armaments.

Additionally, not all of the PRC’s “hard power” is directly classified under the military, and therefore goes unrepresented in the PRC’s defense budget. Many experts believe China’s defense budget topline does not include many military relevant expenses such as space activities, large portions of research and development, construction, and paramilitary forces.

Yet numerous paramilitary and civilian reserve organizations make up a significant portion of Beijing’s military might. For example, the China Coast Guard (CCG), which operates military frigates and other vessels, is organized under the People’s Armed Police, separate from the central Chinese military. Owing to the blurred lines of military-civil fusion, the PRC has created armed reserve forces of civilians, such as the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM), able to be quickly mobilized in the event of conflict. Beijing also mandates its domestic commercial ships be built with certain military specifications to augment the Chinese fleet during a potential future war. When commandeered, these thousands of additional “civilian” ships and their crews could be easily repurposed for activities such as transporting military personnel and equipment.

While Congress considers legislation to better approximate China’s military spending, the trend is clearly nothing but upward while America’s defense budget declines.

No comments:

Post a Comment