Yukon Huang

Led by calls from the United States, the G7 summit in Hiroshima, Japan, highlighted a need to reduce the Group of Seven nations’ dependency on China for critical goods and shift their supply chains towards friendlier nations. Senior US officials laboured to point out that the intention was not to decouple but to de-risk.

This represents a shift from former US president Donald Trump’s fixation on curbing the trade deficit with tariffs after he took office in 2017. President Joe Biden’s foreign policy has been guided by the theme of protecting America’s middle-class workers. He has added more restrictions on China’s access to US hi-tech products and curbed financial relations. Beijing sees these measures as a threat to China’s technological ambitions and growth prospects.

So far, Washington’s actions have little to show for results. According to official US data, America’s merchandise trade deficit with China was larger last year than when Trump took office, and the overall trade deficit is at a record high. Moreover, US imports of manufactured goods have not moderated, with import penetration rising to 34 per cent from 31 per cent in 2017.

But there has been a dramatic decline in China’s importance to US trade. China accounted for 47 per cent of the US trade deficit in 2017, but just 32 per cent last year. US imports increased by about US$900 billion from 2017 to 2022, but China’s share declined from 22 per cent to 17 per cent.

Meanwhile, China’s exports to the world have risen to record highs in recent years. China may be exporting less directly to the US, but it is exporting more indirectly – supplying key inputs to other countries that have stepped up exports to the US, especially Vietnam and Mexico. China’s exports to Vietnam, for example, have more than doubled since 2017, nearly tripling the trade surplus to US$60 billion last year.

China’s exports to Mexico also increased, by nearly 30 per cent last year, amid a surge in foreign investment by Chinese companies seeking tariff-free access to the US market. Hisense, for example, has poured US$260 million into a home appliance park in Mexico while Growatt, a solar equipment maker, has established a factory in Vietnam.

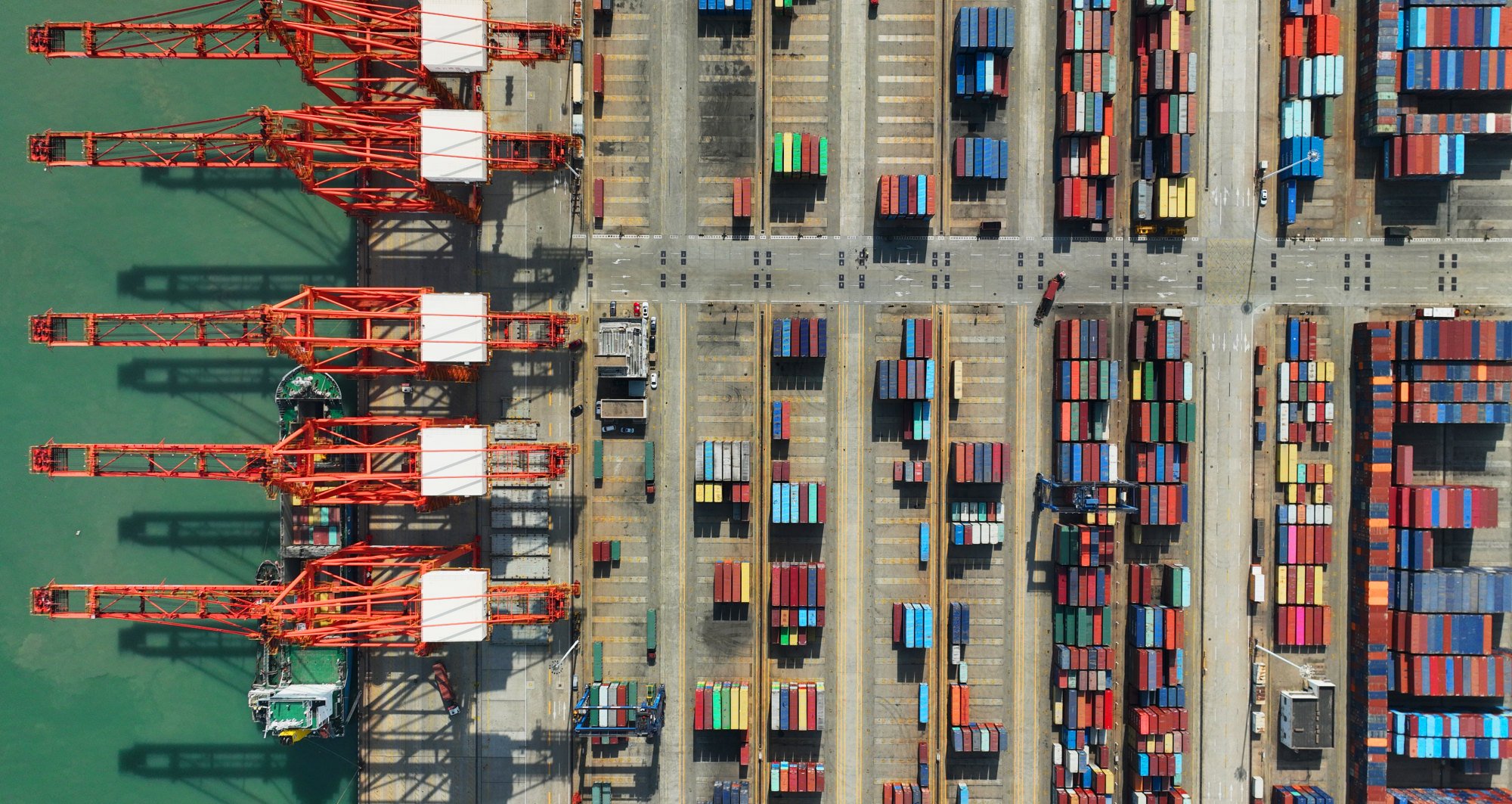

An aerial photo shows the container terminal at Lianyungang Port, in east China’s Jiangsu province, on May 9. China’s exports to the world have risen to record highs in recent years.

India is another notable example, given its strategic importance for Washington. A recent Indian government-backed study questioned the feasibility of decoupling from China since imported intermediate goods from China are preferred by many companies. Indian imports from China soared last year to US$102 billion, up 74 per cent from 2020.

G7 member Germany is among the top exporters to the US market, but its companies are also highly dependent on China for key inputs. China is Germany’s largest trading partner, with imports from China increasing by 46 per cent from 2020 to 2022.

Scepticism that China can maintain its export leadership draws on reports of foreign companies relocating. Historically, companies with foreign investment paved the way and accounted for the bulk of China’s exports. But, over the past decade and half, their share of China’s exports has declined to 34 per cent from over 58 per cent while China’s exports have continued increasing, indicating that its export capacity is no longer dependent on foreign expertise.

If the US goal was to curb China’s hi-tech exports, that has also failed. Hi-tech exports, which account for about 30 per cent of China’s exports, have continued to grow rapidly. Moreover, the share of hi-tech exports handled by foreign-invested enterprises fell from 70 per cent in 2011 to 25 per cent in 2020.

Tesla CEO Musk makes surprise trip to Beijing as US-China tech war escalates

More generally, China has moved on from being largely an assembler of imported components to a manufacturer of sophisticated products. This has made China more self-sufficient, with imports as a share of its economy falling from a high of around 28 per cent, after joining the World Trade Organization, to about 15 per cent last year.

For the West, concerns about dependency are often cast in terms of China’s dominance in producing critical goods such as pharmaceuticals or the lithium essential in most batteries. But it can also be reflected in China’s capacity to supply a broad range of goods. By developing alternative markets, China’s share of global exports has increased from 13 per cent to over 15 per cent over the past five years (from 4 per cent in 2001).

This explains why China’s share of global manufacturing continues to increase, from 26 per cent in 2017 to 31 per cent in 2021. In sum, despite the trade war, the world has become more dependent on China while China has become less dependent on the world.

China’s dominance as a manufacturing power will endure, despite US punitive actions. The US regulations introduced last October that limit China’s access to advanced semiconductors, which has drawn support from others like Japan, may be a possible chokehold on Beijing’s technological ambitions.

But China is already making efforts to circumvent such restrictions. Moreover, Europe’s green transition will be impossible without China, as the Dutch trade minister Liesje Schreinemacher warned recently, given China’s huge lead in solar and wind energy and, increasingly, electric vehicles.

A possible November meeting at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum between Biden and President Xi Jinping offers an opportunity to move away from a zero-sum game in trade relations. The US is unlikely to take the initiative, given domestic political pressures, but Beijing could take the first step by dropping retaliatory tariffs.

In areas of mutual concern, such as climate change, Beijing could also offer to share its advances in green technologies. All this suggests the need for both sides to seek a more constructive approach in dealing with trade and technology issues.

No comments:

Post a Comment