KATJA GRACE

The window of what AI can’t do seems to be contracting week by week. Machines can now write elegant prose and useful code, ace exams, conjure exquisite art, and predict how proteins will fold.

Experts are scared. Last summer I surveyed more than 550 AI researchers, and nearly half of them thought that, if built, high-level machine intelligence would lead to impacts that had at least a 10% chance of being “extremely bad (e.g. human extinction).” On May 30, hundreds of AI scientists, along with the CEOs of top AI labs like OpenAI, DeepMind and Anthropic, signed a statement urging caution on AI: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

Why think that? The simplest argument is that progress in AI could lead to the creation of superhumanly-smart artificial “people” with goals that conflict with humanity’s interests—and the ability to pursue them autonomously. Think of a species that is to homo sapiens what homo sapiens is to chimps.

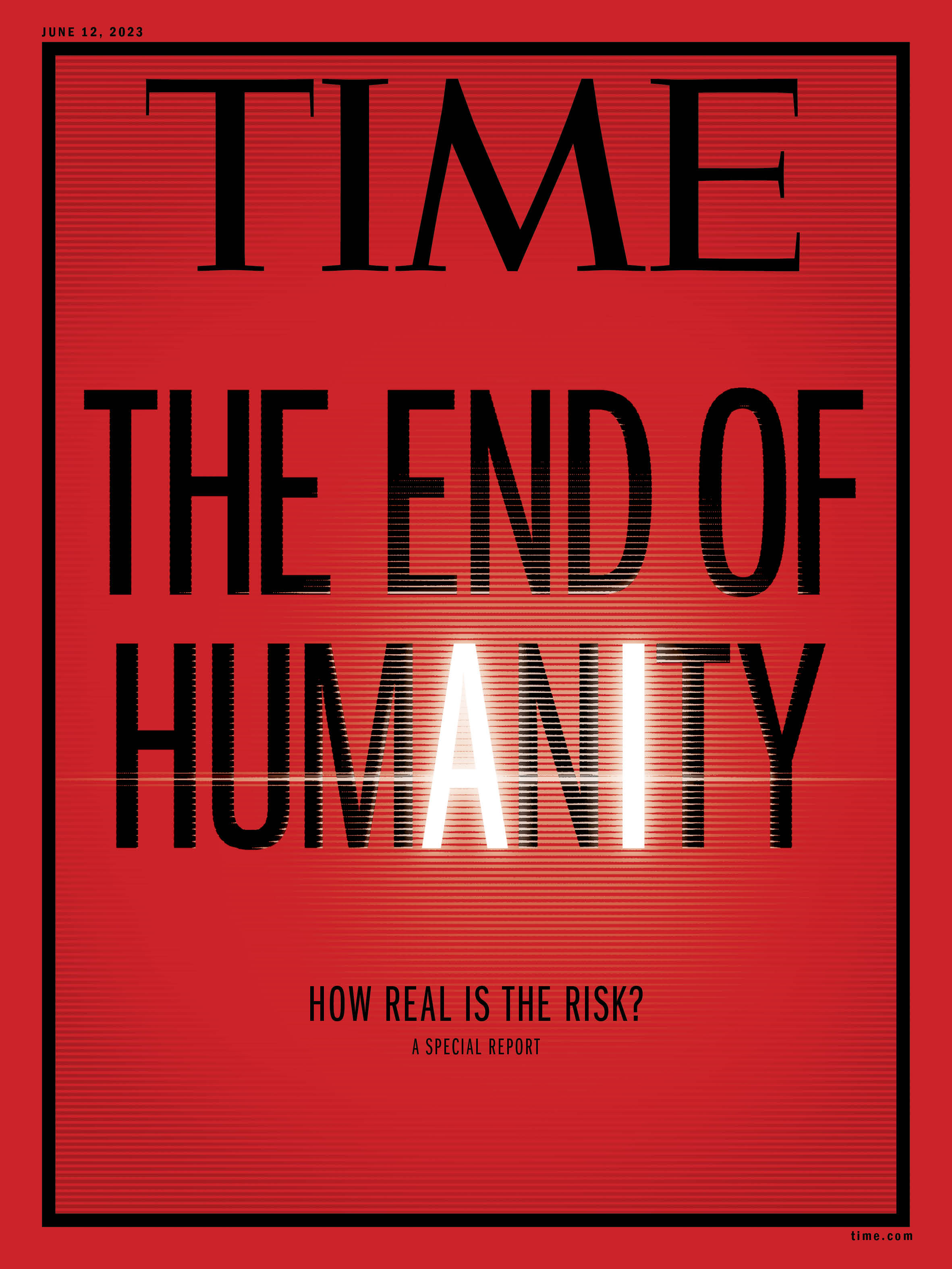

TIME illustration

Yet while many fear that AI could mean the end of humanity, some worry that if “we”—usually used to mean researchers in the West, or even researchers in a particular lab or company—don’t sprint forward, someone less responsible will. If a safer lab pauses, our future might be in the hands of a more reckless lab—for example, one in China that doesn’t try to avoid substantial risks.

This argument analogizes the AI situation to a classic arms race. Let’s say I want to beat you in a war. We both spend money to build more weapons, but without anyone gaining a relative advantage. In the end, we’ve spent a lot of money and gotten nowhere. It might seem crazy, but if one of us doesn’t race, we lose. We’re trapped.

But the AI situation is different in crucial ways. Notably, in the classic arms race, a party could always theoretically get ahead and win. But with AI, the winner may be advanced AI itself. This can make rushing the losing move.

Other game-changing factors in AI include: how much safety is bought by going slower; how much one party’s safety investments reduce the risk for everyone; whether coming second means a small loss or major disaster; how much the danger rises if additional parties pick up their speed; and how others respond.

The real game is more complex than simple models can suggest. In particular, if individual, uncoordinated incentives lead to the sort of perverse situation described by an “arms race,” the winning move, where possible, is to leave the game. And in the real world, we can coordinate our way out of such traps: we can talk to each other; we can make commitments and observe their adherence; we can lobby governments to regulate and make agreements.

With AI, the payoffs for a given player can be different from the payoffs for society as a whole. For most of us, it may not matter much if Meta beats Microsoft. But researchers and investors chasing fame and fortune might care much more. Talking about AI as an arms race strengthens the narrative that they need to pursue their interests. The rest of us should be wary of letting them be the ones to decide.

A better analogy for AI than an arms race might be a crowd standing on thin ice, with abundant riches on the far shore. They could all reach them if they step carefully, but one person thinks: “If I sprint then the ice may break and we’d all fall in, but I bet I can sprint more carefully than Bob, and he might go for it.”

On AI, we could be in the exact opposite of a race. The best individual action could be to move slowly and cautiously. And collectively, we shouldn’t let people throw the world away in a perverse race to destruction—especially when routes to coordinating our escape have scarcely been explored.

No comments:

Post a Comment