NILESH CHRISTOPHER

In December 2021, as the world struggled with the Covid-19 pandemic, the tech sector faced an unanticipated challenge: an acute shortage of semiconductor chips. Taiwan is the world leader in semiconductor chip manufacturing, and the pandemic-triggered lockdowns increased delivery times for the chips. This walloped the production of everything, from cars to mobile phones.

In December 2021, as the world struggled with the Covid-19 pandemic, the tech sector faced an unanticipated challenge: an acute shortage of semiconductor chips. Taiwan is the world leader in semiconductor chip manufacturing, and the pandemic-triggered lockdowns increased delivery times for the chips. This walloped the production of everything, from cars to mobile phones.Now, even as the pandemic-related bottlenecks have eased, conversations around semiconductor chips — tiny circuits that manage the flow of electric current in equipment and devices — refuse to go away. Semiconductors have, in fact, become a major geopolitical issue. They are at the heart of the ongoing trade war between Washington and Beijing, as the U.S. has banned the supply of advanced chip-making software to China.

Meanwhile, India has made an ambitious push to position itself as an alternative to China, announcing a $10-billion incentive plan to boost semiconductor manufacturing in the country. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi’s goal of establishing India as a semiconductor manufacturing hub is still a work in progress. Over the past two decades, India has had two failed attempts to build semiconductor plants. The moment might pass in 2023, too, if the country doesn’t recognize its potential.

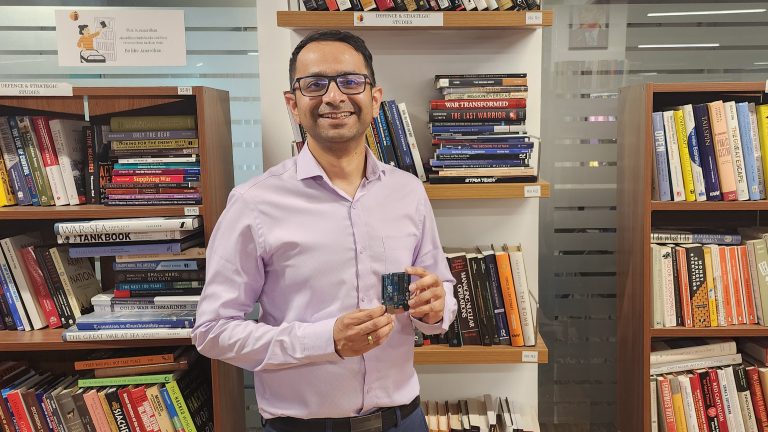

Rest of World met Pranay Kotasthane, chair of the High-Tech Geopolitics Programme at Takshashila Institution, a nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank based in Bengaluru, to talk about what the U.S.-China chip war means for India. His latest book Missing in Action looks at public policymaking in India and why the state functions the way it does. During the interview, Kotasthane talks about how chips became geopolitical flashpoints and the jumbled priorities of India’s semiconductor policy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did semiconductors become a geopolitical issue?

China has an impressive technology stack on many things like AI, quantum computing, or 5G. But semiconductors are one area which is their weakness, and they don’t have any advanced manufacturing capabilities. If China wants to do 5-nanometer or 7-nanometer manufacturing, they are not able to do it. [A high-tech processor chip is below 45 nanometers; the lower the number, the more advanced and costly the chip-making process is.] They are still dependent on Taiwan. Of all the areas in tech, this was one area where the U.S. thought they actually have a disproportionate leverage over the adversary. So that’s why it became a flashpoint. My guess is that the U.S. chip export controls and restrictions have pushed back China’s semiconductor story by a decade.

The other reason is just Taiwan’s centrality. More than 90% of the really advanced chips are made in Taiwan. Foundries in Taiwan do contract manufacturing of chips for all global semiconductor giants. The worsening relations between China and Taiwan mean that governments and companies can no longer ignore the implications of a Chinese economic blockade or military takeover of Taiwan.

Pranay Kotasthane, chair of the High-Tech Geopolitics Programme at Takshashila Institution. Nilesh Christopher/Rest of World

Pranay Kotasthane, chair of the High-Tech Geopolitics Programme at Takshashila Institution. Nilesh Christopher/Rest of WorldThrough the 80s and 90s, when East Asia was leveraging this opportunity, did India miss the bus? Were there previous attempts to set up fabrication plants in India?

A few attempts were made. We had a government-run fab: the Semi-Conductor Laboratory, which is in Chandigarh. It still exists, but doesn’t make any commercial chips. It makes chips for the Indian Space Research Organisation. In the 1980s, it was not far behind the cutting edge, but since it was not focused on commercial production, we lost out. In 2006, there was an attempt to set up a fab in Hyderabad; and another attempt in 2013.

But there were a couple of bottlenecks: One, there were no downstream companies. You finally made chips — who will take these chips and make products on top of them? Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) weren’t there. Two, India is not doing well in manufacturing industries due to a complex tax structure. In 2011, British telecoms operator Vodafone had to pay $6.7 billion in retrospective tax. These are very important precedents that any fab manufacturer will take into account.

“Design and testing are two places where we actually have advantages.”

Fab is an investment where you put $12 billion now, and the first chip will come four years down the line. You start making profit after you have perfected your recipe. So anyone who’s investing is going to look at policy consistency, how good the manufacturing environment is, what is the chance of this market developing OEMs. The cost-benefit calculation wasn’t in India’s favor.

What are your views on India’s four semiconductor policies?

My overall sense was that it is in the right direction, but the priorities are a bit jumbled up.

There are three reasons why a government would back semiconductor plants: capitalize on our strengths, reduce vulnerabilities in the supply chain, and reduce import dependence on China.

I think the Indian government’s priority is on reducing vulnerabilities, which is through fabs, because we have zero commercial manufacturing capability of any chip. The investment in the display fab is with the objective of reducing imports from China.

The investment in design, through the design-linked incentives, is from the perspective of building on our strengths. Government wants to support 100 local firms working on integrated circuit and chipset designs. The other focus is on the outsourced semiconductor assembly and test, where India has a comparative advantage given that we have low-cost labor. Design and testing are two places where we actually have advantages.

I don’t think we need to invest in display fabs, because if Chinese companies don’t provide them, we can buy them from Japan or South Korea. It’s a huge cost we are putting up for this display fab.

My view is that you either set up a fab, or you put the money in outsourced assembly and testing, where we have a competitive advantage. We have a lot of scope and talent. In some estimates, we have 20% of the total design workforce in the world. The India Electronics and Semiconductor Association claims that around nine out of 10 chips that go into the market will have some Indian design center work behind them. So there is capability, but now that needs to be translated into intellectual property and new products that are made from India.

The Indian government said it will be approving two chip manufacturing plants in 2023. Foxconn’s chairman has met Modi twice. Apple has tripled iPhone output to $7 billion in a shift from China. Are these early successes? How far along is India in reshoring the semiconductor supply chain?

Apple’s progress is good news, but it is not about semiconductors. It’s about assembling mobile phones, not the chips that go into mobile phones.

There is no approved proposal for semiconductor fabrication yet. All we have is memoranda of understanding. These are all advanced interests that companies have expressed. Now negotiations are on about how much subsidies state governments will give versus how much the federal government will cough up. Those conversations are ongoing, but we don’t have any approvals yet.

If I have to speculate — very wild speculation — maybe we will get one fab with the interest of the government, with the geopolitics and the entire opportunity around it.

“If we think that we have to do every part of this on our own, we will end up trying everything and achieving nothing.”

What makes you hopeful about India’s current attempt at setting up a fab?

One thing to realize in the fab story is that earlier attempts in 2006 and 2013 also had all these government incentives, but those incentives were of the nature of reimbursement. Now the government is putting upfront capital investment.

They modified the policy to say that irrespective of the chip fabrication you do, even if you’re doing the 65-nanometer analog chip [an older technology], we will still back you 50%. So this was a realism that came into government policy, which I thought was good. It’s a ladder you have to climb. Suddenly no one is going to start a 5-nanometer [the most advanced] fab in India. The government also lifted the cap on funding, and is open to financing beyond $10 billion if required. That’s why I’m more hopeful.

Your analysis shows India imports 64% of its chips from China, and that will only grow as we increase our capacity. What are the perils of looking at electronic imports through a national security and self-sufficiency lens?

We should look at self-strength, and not self-sufficiency.

Especially in semiconductors, no country is self-sufficient. So ideally, you will have these cross-border flows. The peril of this is that once you start looking from this national security lens, you’re going to say, let’s stop that. Let’s increase import duties on that. Now, for example, if Apple is making mobile phones in India, the chips might be coming from China. These are not chips that are designed in China. They might have been designed by Apple; they might have been made in TSMC — only the assembly might have been done in China. But if we are so focused on reducing import, then how will manufacturing happen in India? Or how will Samsung manufacture in India? Their costs will go up if you’re going to increase import duties or make it difficult for them to source globally. If our aim is to develop a robust electronic ecosystem, it’s fine if chips are coming from anywhere.

Is there a constant point of conflict for these companies with high import duties on chips?

Yeah, there is. Right now, India is a signatory to the Information Technology Agreement and the World Trade Organization, which said that we should make custom duties on all electronics or semiconductors zero. But it’s not just semiconductors, there might be equipment that has import duties. Components have import duties. So that hurts these companies.

We should not look at it as a self-sufficiency argument; we should look at two goals for the semiconductor supply chain: One, you will need to have enough redundancy in the supply chain, such that your adversary is not the sole player in any one segment. Two, you need to collectively have expertise in every segment of the supply chain, so that you can outpace your adversary.

In your paper, you make the case that Quad members — Australia, Japan, India, and the U.S. — have expertise in specific domains of chip supply, and they should band together. Why?

That is a good grouping to start off because you have complementary strengths. If you are able to ensure that among these four countries, you have enough redundancy, and ensure collective expertise in every part of the supply chain, you don’t have a risk. If we think that we have to do every part of this on our own, we will end up trying everything and achieving nothing.

The U.S. is the indisputable leader in design companies. But manufacturing is tough there, as the costs are prohibitively high. Japan has strength in the materials that go into semiconductor manufacturing. There are very specific gasses you need for etching, you need photoresist, you need very specific chemicals which have very high levels of purity and precision. There are two or three companies in each of those areas from Japan itself who have perfected that. Australia can supply silica, gallium, indium: elements that you need during manufacturing of semiconductors. Also, where will semiconductors be used? Say, electric vehicles? Australia is doing a lot of work on that.

India’s competitive advantage, as I said, is talent. Even if the U.S. introduces the CHIPS and Science Act, they don’t have enough engineers to execute many of the investments. Who will do the work? Chinese talent moving to the U.S. will face more scrutiny there because of geopolitical tensions. So it’s Indian talent which will be used. India also has the cost advantage: Companies that want to do assembly, we can do that quickly at lower costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment