Amit Dasgupta and Don McLain Gill

Two facts unabashedly stare humankind in the face. First, that history repeats itself, and second, that we should never underestimate the addictive power of human stupidity. There is a third fact: We are no longer bound by global solidarity but by a deep divisiveness that threatens to plunge us into chaos and tear us apart, suggesting, thereby, that there is no room for peace.

Can we challenge these assumptions?

Consider, briefly, the prevailing global scenario. We are yet to recover from the devastating effects of the pandemic. Global real GDP is forecasted to grow by only 2.2 percent in 2023. The Russia-Ukraine war shows no signs of abating. Business and consumer predictions for Europe are gloomy, as it struggles with substantial headwinds that will shackle its economy and trigger rising unemployment. The global order faces a real challenge with the declining influence of the United States and the adversarial rise of China. None of this is good news.

As Japan takes up the mantle of leadership of the Group of Seven (G-7) this year, it is provided with an opportunity to contribute to the agenda and direction all seven developed democracies will take amid the unfolding turbulence in the world. Being the only Asian member of the G-7, Japan’s presidency is expected to also reflect Tokyo’s unwavering commitment to deepen, expand, and operationalize the G-7 framework of cooperation with a special emphasis on the Indo-Pacific.

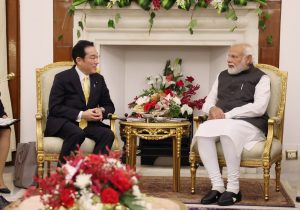

However, acknowledging the structural shifts taking place in the international distribution of power, Japan realizes the need to work more intently with a rising India. Both Tokyo and New Delhi converge in their strategic visions for the Indo-Pacific; hence, it is in Japan’s interest to utilize its G-7 presidency to better institutionalize its strengthening partnership with India to complement its overarching objectives in the region and synergize a more effective cooperative framework with the rest of the G-7 members.

A Sharp Focus on China

Recently, at the annual summit of China’s parliament, President Xi Jinping said that he is preparing China for war. Whether this refers to an invasion of Taiwan or the capture of more islands to control the Pacific, and thus international sea trade routes, is a matter of speculation. What is, however, clear is that Xi’s aggressive public pronouncements, combative style, and hegemonic assertion of Chinese territory have triggered an unprecedented arms race in the Indo-Pacific. From AUKUS to Japan radically changing its defense policies, to intensified defense and security collaboration between India and Australia, to name a few, all are responses to a perceived and imminent China threat.

Xi’s authoritarian and egocentric ambitions continue to motivate his solidification of national power. However, if he is to go down in contemporary Chinese history as “the great leader,” he needs to be remembered for restoring China’s lost pride and establishing its dominance in global affairs, and achieving global acknowledgment of the pre-eminence of China under his leadership. His ambitious agenda allows for this to happen only through military power and economic bullying. Moreover, Xi’s China is fueled by hyper-nationalism as a means to solidify his domestic political position. Thus, Beijing’s belligerent external policies are aimed at sustaining domestic cohesion, resulting in limited room for peaceful diplomacy due to fears of seeming weak at home.

During the G-7 foreign ministers’ meeting on April 18, Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa highlighted that the way the crisis in Ukraine is unfolding may also be eventually witnessed in Southeast Asia, given China’s growing assertiveness and the proliferation of its gray zone strategies, along with its increasing militarization of the South China Sea at the expense of the sovereignty and sovereign rights of the Southeast Asian claimant countries.

With the tumultuous dynamics of Indo-Pacific geopolitics brought by the assertive rise of China and the limits of U.S. influence, Japan has pragmatically reoriented its foreign policy towards a more security-driven approach, particularly under the government of Prime Minister Kishida Fumio. To illustrate Tokyo’s willingness to play a bigger and more proactive role as a responsible security provider of the Indo-Pacific, the Japanese Foreign Ministry is expected to spend over $15.2 million to contribute to the security capacities of like-minded regional countries.

Leveraging the Japan-India Strategic Partnership

However, while the G-7 members have indicated their commitment to providing security and development in the Indo-Pacific, the lack of a practical understanding by the West regarding the dynamic and diverse nature of the East provides undeniable challenges for them in effectively maximizing their influence and role in the region. Acknowledging this reality, Tokyo has been consistently enhancing, deepening, and broadening its strategic partnership with India. This also complements India’s close and vital strategic partnerships with the rest of the G-7 members. Consequently, the invitation to India to participate in the incoming G-7 Summit offers Japan a unique opportunity to carve an alternative, practical, and more organic approach to Indo-Pacific affairs.

Being the fifth largest economy with a vast and formidable military, India is seen not only as a significant partner but also a natural contributor to the stability and development of the Indo-Pacific, given its deepening strategic ties with the diverse countries of the region. Moreover, New Delhi’s external engagements have always been centered on respect for diversity, transparent communication, and democratically driven cooperation based on mutual goals and interests. More critically, India has also been at the receiving end of China’s expansionist interests, making it a pragmatic partner to address this issue more efficiently.

Accordingly, while both Tokyo and New Delhi have been able to push back China’s assertive maneuvers on several occasions, both Indo-Pacific powers believe that open diplomatic communication will be necessary to create an environment for lasting peace. This level of political maturity shared by both countries complements the interests of regional countries that do not wish to fall deeper into a binary-driven situation brought by the intensifying China-U.S. power competition. Both Japan and India also have vast material capabilities that can positively contribute toward the capacity-building of friendly partner countries, while also ensuring that cooperation will be based on mutual concerns and goals rather than bloc politics.

Therefore, with Japan’s presidency comes a significant opportunity to incorporate its expanding partnership with India in the context of the G-7’s broader strategic roadmap for the region. This will also not only catalyze a more robust approach to the region but also serve as an impetus for a more equitable framework for cooperation between the Global North and the Global South.

No comments:

Post a Comment