Allison Fedirka

Immigration is a politically divisive issue in the United States. It’s easy enough to explain, even if it’s difficult to legislate: The U.S. has more economic opportunities than most other countries, and its 1,900-mile-long, relatively uninhabited and sparsely monitored border is an immigrant’s best chance at entering the country with their legal status up in the air. And with pandemic-related emergency measures set to expire later this month, Washington is bracing for a new influx of Latin American migrants.

But there’s a geopolitical aspect to Western Hemispheric migration that often gets overlooked in domestic political discourse. For the United States, the migration question is not just about border security; it’s about how it manages bilateral ties with Latin American countries at a time when intra-regional tensions are on the rise.

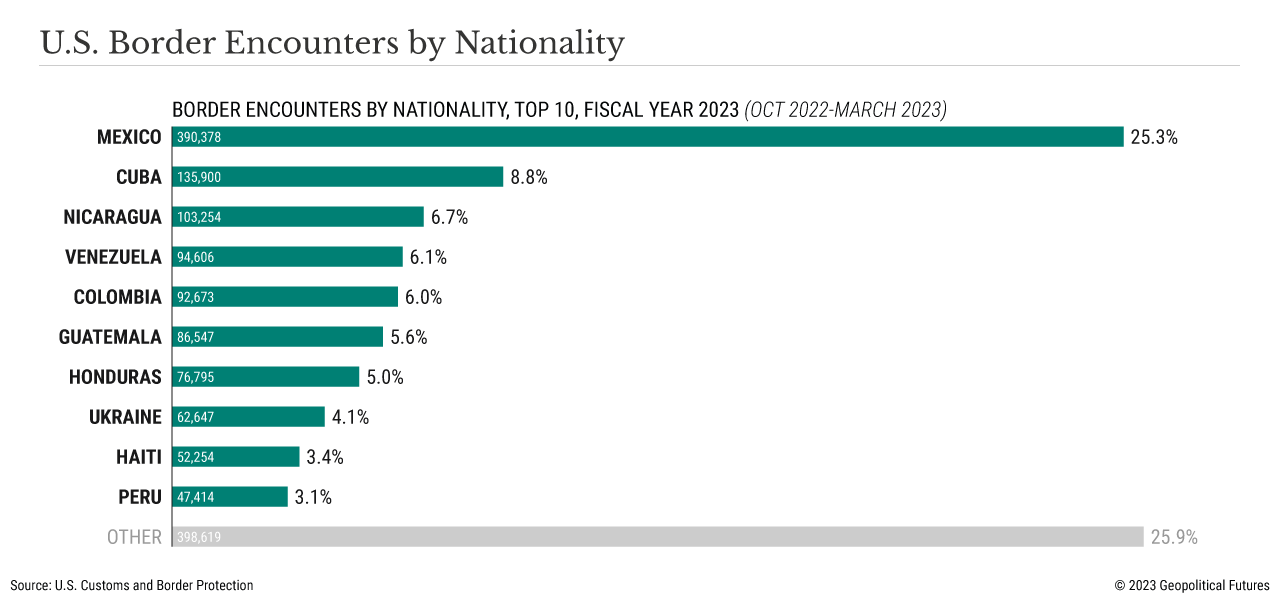

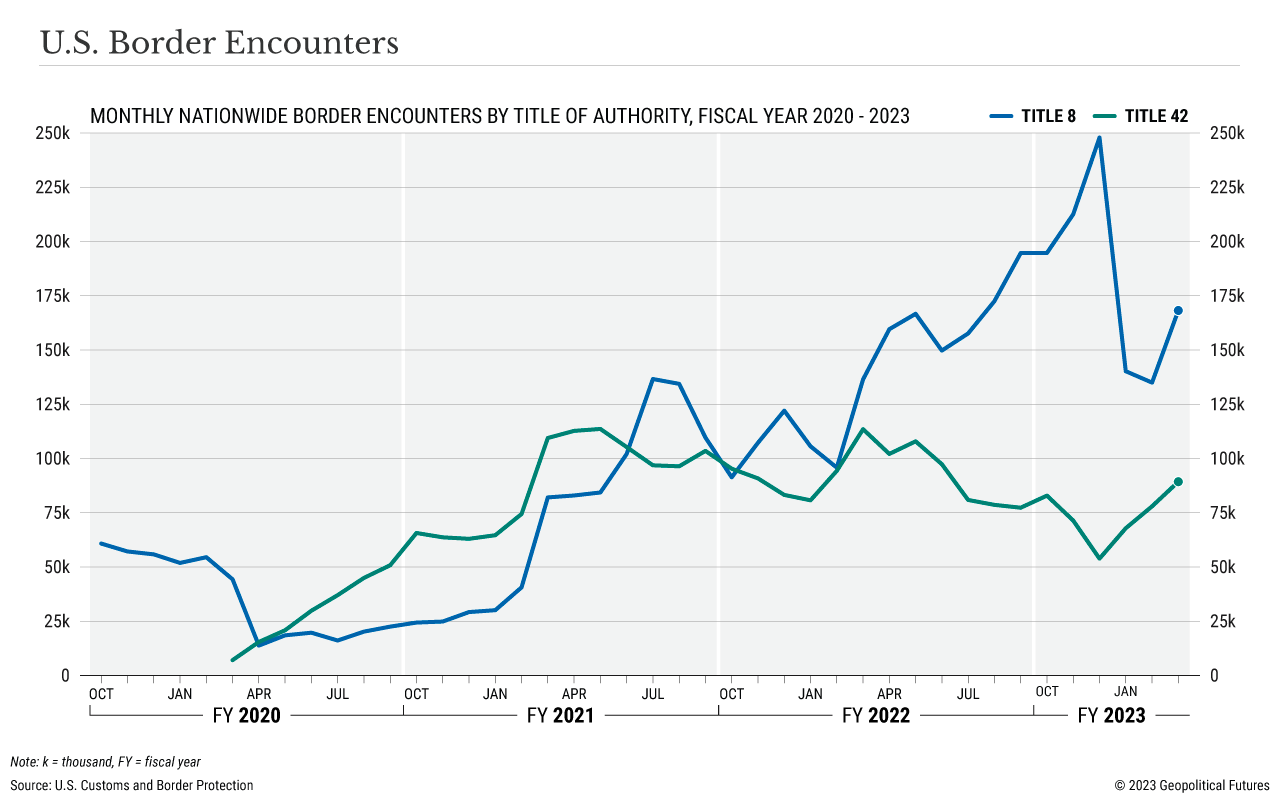

The pandemic-related measures in question, known as Title 42, gave Washington the ability to quickly remove migrants from the U.S. over health concerns. It was a politically expedient tool at a politically sensitive time, but the U.S. has plenty of those at its disposal. A few days ago, for example, Washington announced its plans to reempower Title 8 to control migration at the border. (Title 8 refuses entry to any immigrant who helps another immigrant illegally.) Moreover, it introduced special visa programs and coordinated plans for returns to Mexico for migrants from some of the most prominent countries. These programs limit the number of entries by country and, among other criteria, require legal travel for admission into the U.S. They started last year with Venezuela and expanded this year to include Cuba, Nicaragua and Haiti, and by this spring, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala are expected to be included. The U.S. is also introducing new migration centers in Guatemala, Colombia and Cuba to deal with administrative work and visas before individuals travel to the U.S.

This is hardly a comprehensive list, but all these measures betray the real reason the U.S. cares so much about migration – namely, how the political and economic climate of Latin America affects the United States. The entire region has struggled to recover to pre-pandemic economic levels and still experiences poor economic growth and high inflation for basic goods. Poor economic conditions and scarce state resources have created opportunities for organized crime groups to expand and fill the void. Many cartels have taken advantage, exploiting migrants by demanding passage fees or forcing them into human trafficking rings. These conditions have also aggravated political unrest throughout the region and left many Latin American governments struggling to support their economies as they try to accommodate thousands of migrants crossing their borders.

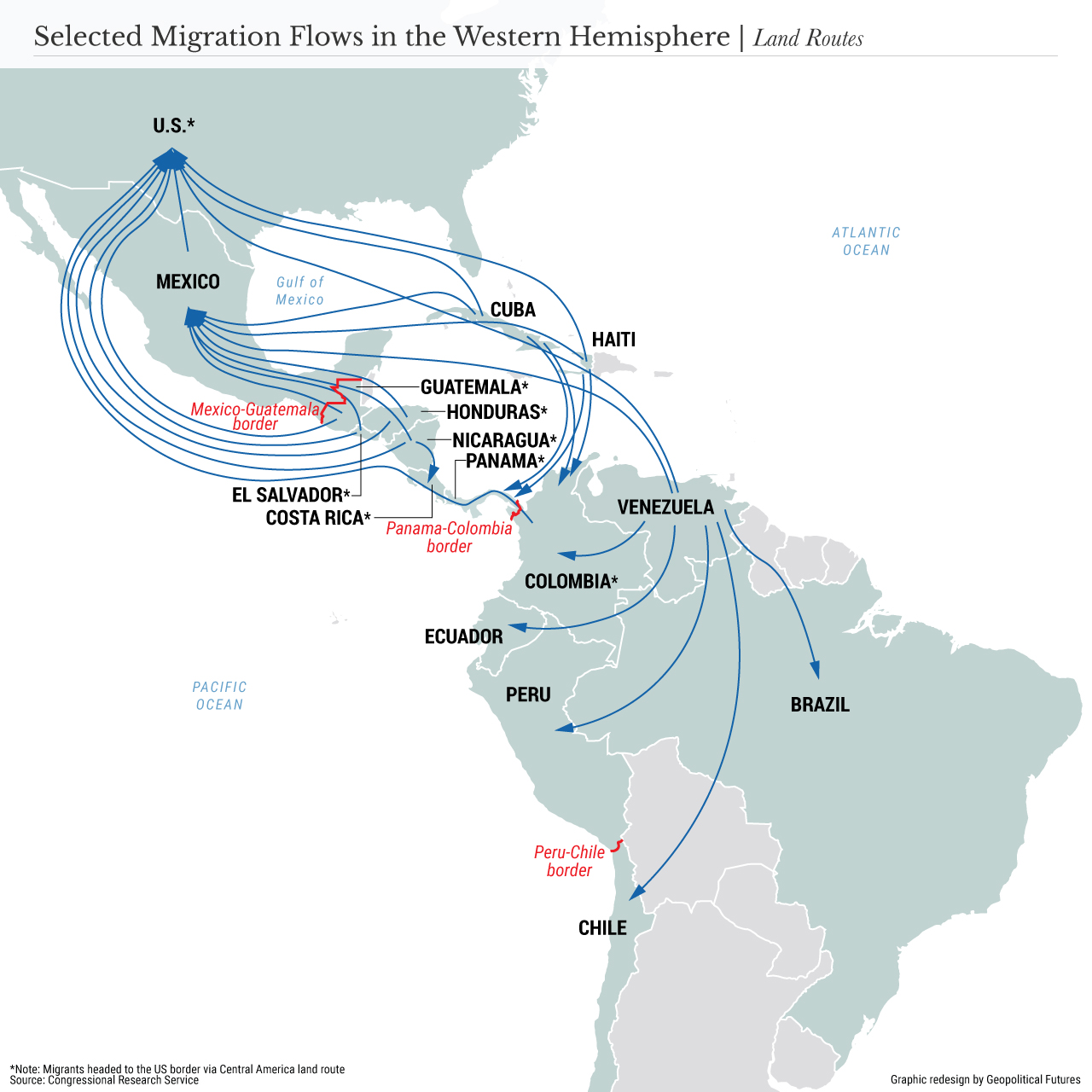

Under these circumstances, intra-regional tensions among Latin American countries are expected to grow. Governments often try to pass the burden of migration flows to other countries, thereby reducing the drain on their own resources. The seeds of conflict have already started to sprout in a few important areas: the Mexico-Guatemala border, the Peru-Chile border, and the Panama-Colombia border. In the case of Mexico and Guatemala, a fire at a Ciudad Juarez migrant center killed 40 individuals, over half of whom were Guatemalan. The Guatemalan government considered the deaths a result of negligence and poor management because the guards allegedly didn’t have the keys and fled the fire. In the case of Peru and Chile, migrants were allegedly expelled from Chile (though some reports suggest they left in an attempt to return home). Peru has since declared a state of emergency, sent security forces to all its border areas and increased efforts to combat criminal activity along the border area. In the case of Panama and Colombia, several incidents have riled tensions, the most notable of which took place in mid-April, when Colombia’s foreign minister made a public statement referring to the Department of Panama, implying the country was part of Colombia, and disinvited Panama from the Bogota summit on the future of the Venezuelan government.

These three regions share a couple of important characteristics. First, all of them have been historically contested areas and flashpoints for bilateral conflict. Each country has inherent geopolitical interests and a desire to keep potential adversaries at bay. In other words, migration is a symptom of their conflicts, not a direct source. Second, all six countries have traditionally close ties with the United States. This puts Washington in a situation in which two allies are at odds with each other at a time when it needs to work with both.

Of these three disputes, the one at the Panama-Colombia border is the most concerning to Washington because of its potential to impact the Western Hemisphere. Access to and security of the Panama Canal remains central to U.S. strategy for hemispheric security, which undergirds Washington’s ability to project power globally. It’s why, for example, the U.S. actively supported Panama’s 1903 separation from Colombia and slid in as an economic guarantor of the new country to help reduce foreign (Colombian) influence over the canal. And it’s why the U.S. military invaded Panama in 1989 to replace the Noriega regime with a government more inclined to support U.S. interests. More recently, the U.S. has leaned on Colombia as part of its efforts to combat drug trafficking and, separately, to counter Venezuela.

The Darien Gap is a focal point of the region, one that marks the intersection of territory, migration flow and U.S. interests. This inhospitable environment in southern Panama and northern Colombia has served as a barrier between the two countries for centuries. But its terrain and lack of state presence make it a hotbed for a host of illegal activities, including migration and drug trafficking. Travelers congregate in Colombia before trekking north through the Darien Gap en route to the U.S. via Panama. The uptick in migration in recent years has thus created a huge burden for Panama and Colombia. Last year, some 250,000 individuals crossed the Darien Gap, equivalent to about 5.7 percent of Panama’s population of 4.4 million. This year, an estimated 127,000 migrants have crossed into Panama. And Panama’s National Migration Service warns that at the present rate that number could climb to 400,000. Colombia now hosts 2.5 million Venezuelans in its territory, the equivalent of about 4.8 percent of its population.

Given that the Darien Gap is a natural chokepoint for migration and illicit activity, the U.S. has an interest in curbing transit through the area. Washington also has an interest in making sure bilateral tensions between Colombia and Panama do not escalate. Achieving both goals requires the U.S. to work with both countries. Thus in early April, the U.S., Colombia and Panama announced a two-month operation to curb migrant smuggling in the Darien Gap. The governments also appear to be coordinating on creating new pathways to legalization for migrants.

The structural problems driving Latin American migration put the U.S. in somewhat uncharted territory when it comes to managing regional relationships. Historically, U.S. engagement has been marked by intervention, economic domination and political strong-arming. For much of the 20th century and the first two decades of the 21st century, the line between friend and foe was clearly drawn by political and economic ideology. The U.S. has, for example, stressed democracy and open markets over heavy-handed government policies and centralized economies – first against the Soviet Union and now against China. But the current economic and political environments no longer allow for a zero-sum game. The U.S. understands it cannot stop countries from cutting off trade with China, and Washington cannot take for granted that traditional allies will automatically fall in line, especially as economic and political pressures pit regional countries against one another.

Though Washington and its traditional allies still share plenty of interests, managing these relationships has become increasingly difficult. Navigating this landscape will require the U.S. to develop a more intricate and nuanced approach than it has employed in the past to ensure hemispheric security. This is particularly true given that the scenario in which the U.S. finds itself between two fighting allies creates opportunities for outside players, like China, to insert themselves and try to capitalize on the situation. Managing such dynamics requires a large toolset, with approaches customized to each situation. The stakes are high, and failure could jeopardize the very foundation of U.S. security and stability.

No comments:

Post a Comment