THERESA HITCHENS

Tech. Sgt. Michael Vandenbosch, 22nd Space Operations Squadron defensive counter-space operator, uses software to identify interference to a specific satellite at Schriever Space Force Base, Colorado, Dec. 16, 2019. (US Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Jonathan Whitely)

Correction 05/18/2023 at 4:17 pm ET: The original story incorrectly listed the amount of the SCAR contract. The number has been updated, and the contract terms clarified at the request of SSC.

SCHRIEVER SFB — As the number of US government satellites continues to grow, the Space Force’s already outdated Satellite Control Network (SCN) for keeping them flying is in real danger of being overwhelmed, according to officers at the 22nd Space Operations Squadron responsible for that mission.

“What we want everyone to know is that this control network has been working for decades, right, and it was absolutely critical for the growth of the Space Force and our US capabilities across the space domain. But it’s in need of modernization,” Lt. Col. Jaime Garcia, the squadron’s commander told a small group of reporters on a rare tour of the SCN’s operations center here at Schriever SFB in Colorado Springs.

“We need to start focusing on making sure that not only infrastructure at all the individual sites is growing, but also growing the capacity that we’re able to support. Because as we’re seeing… the number of launches is not decreasing. The need for space and space domain capacity is not going to go down,” he said. “[B]ringing in that modernization sooner rather than later is absolutely critical.”

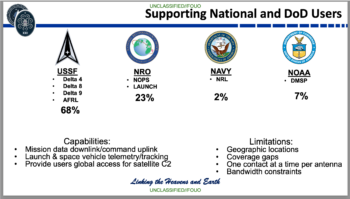

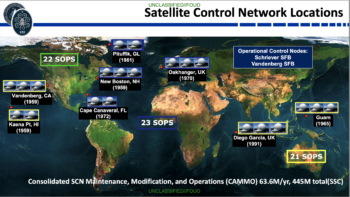

The SCN is primarily used to support launches and early satellite operations, track and control satellites, and provide emergency support to tumbling and lost satellites for constellations owned by the US military, the National Reconnaissance Office, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). As well as the operations center here, the network comprises 19 antennas and ground systems at seven locations around the globe that undertake what are known as TT&C functions — tracking (determining where a satellite is located), telemetry (collecting information about its health and status) and command (transmitting signals to control subsystems and maneuvering satellites if necessary).

The 22nd Space Operations Squadron reports to Delta 6, one of nine components of the Space Force’s primary field command, Space Operations Command, that provides trained Guardians to US Space Command to undertake its portfolio of missions. It is one of three squadrons that has day-to-day responsibility for the SCN, managing the SCN operations center for the entire network, alongside the 21st and 23rd squadrons, which take care of the antennas in the Pacific and the Atlantic theaters respectively.

The operations center here is a 24/7 mission with the crew numbering about 120. Two-thirds of them are civilian, Garcia said, in large part because the training required is so time-consuming, taking between nine and 12 months. A Guardian’s typical assignment time to any one mission is only about three years.

“We do everything from initial launch, where the booster is tracked; initial separation, where the satellite is put into orbit; station keeping; and general operations for satellites… and then final disposition,” Lt. Col. Jason Panzarello, director of operations at the squadron, explained.

He noted that while a number of military constellations — including GPS, missile warning systems, and those used for nuclear command and control — have their own ground control antennas, they also can, and do, fall back on the SCN on occasion.

“Basically, every DoD satellite can operate on our network,” he said.

SCN operators also can see if a satellite is experiencing interference with its command and control functions, whether deliberate jamming or not. During the week of April 23, for instance, the crew assigned to do that defensive counterspace mission saw 17 “anomalies” indicating interference of some sort, although the number of incidents vary wildly.

Panzarello said the squadron has not seen any other nation “actively” trying to jam or confuse US birds. However, he said, China’s manned space station in low Earth orbit never turns off its broadcasting system and thus causes a little interference with satellites crossing its path.

Instead, the leaders of the 22nd Space Operations Squadron are primarily worried about the network’s decreasing viability.

Alarming Report ‘Very Much Portrayed Our Feelings’

As highlighted in a recent report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the SCN’s hardware and computer systems are rapidly nearing obsolescence, while demands for its services are skyrocketing. The government watchdog office also chided the Space Force for not having an up-to-date comprehensive plan for keeping the network operational while working to modernize outdated equipment.

“They very much portrayed our feelings; we had meetings upon meetings with them,” Panzarello said, to nods in agreement from his commanding officer.

“The numbers of satellites will continue to go up. The number of antennas that we have going up is notional at this point,” he added mournfully.

Panzarello explained that the SCN currently is managing more than 200 satellites, plus an ever-growing number of launch vehicles — with the number of launches growing from 36 in 2021 to 42 in 2022. But the SCN’s parabolic antennas used to communicate with them are seriously outdated, relying on mechanical operations to change position and able to contact only one satellite at a time. Thus, the antennas are being increasingly overstressed in trying to keep up with growing on-orbit needs.

Garcia said “the biggest concern” for the squadron is that “the existing infrastructure was was built back in the ’70s.”

That concern was made clear from viewing the large, unwieldy computer stations being used by his crew, not to mention the fact that much of the work is being done on paper.

“It’s still a manually intensive job,” said Panzarello.

Garcia said his team needs “a stronger, more resilient communications architecture, antennas that are able to handle higher throughputs of contacts, and also [modernization of] our scheduling system so that it is able to manage all the contacts.”

According to briefing charts provided by the squadron, the SCN contacts satellites about 155,000 times a year, around 450 times a day. SCN operators use a matrix for scheduling when each individual satellite can contact the SCN and for how long, but conflicts among their TT&C needs are commonplace — even when all 19 of the SNC’s antennas are fully operational.

Millions To Be Spent On Upgrades, But Gaps Remain

The two officers explained that the Space Force is looking at multiple initiatives to try to improve the SCN across the board.

The Space Force’s fiscal 2024 budget request includes a total of $86.5 million for a handful of SCN modernization and augmentation efforts, as well as upgraded cybersecurity — almost double the $42 million appropriated in FY23.

The Space Force’s fiscal 2024 budget request includes a total of $86.5 million for a handful of SCN modernization and augmentation efforts, as well as upgraded cybersecurity — almost double the $42 million appropriated in FY23.This includes integrating new antennas into the network from both other federal agencies and commercial providers to expand TT&C capacity.

The service already has an agreement to utilize some of NOAA’s antennas, Garcia said, and is “working on figuring out how we can leverage commercial companies.”

However, according to the GAO report, there remain challenges to using other existing antennas. The five NOAA antennas that SCN is working to integrate require upgrades and won’t be ready for use until the end of next year. As for commercial antennas, the preponderance of those currently in use do not use compatible bandwidths and/or do not meet DoD cybersecurity standards.

Meanwhile, the Space Rapid Capabilities Office last May launched the Satellite Communications Augmentation Resource program, designed to field as many as 12 new phased array antennas for the SCN by the early 2030s. Unlike the current SCN antennas, phased array models can simultaneously contact between 18 to 20 satellites. The office awarded an Other Transaction Authority agreement with a ceiling of $1.4 billion to BlueHalo in May 2022 for the SCAR effort. Development and delivery of the first prototype antenna is on a cost-plus-fixed fee basis while the remaining antennas are expected to deliver on a firm-fixed price basis.

The first SCAR system delivery is expected in 2025, while the remaining eleven units will be delivered through May 2031, according to a Space Force spokesperson. The service’s FY24 budget funds development, fielding, operations and sustainment of the first antenna.

The end goal of all the SCN plans, according to the Space Force budget documents, is an expanded, fully automated command and control network.

“SCN acquisition strategy is evolving from completing obsolescence, resiliency, and cyber security upgrades for existing satellite C2 network assets to future planning for the evolution of the SCN, Ground Enterprise Next (GEN), and data transmit, receive and transport architectures to increase efficiency and resiliency of SATOPS operations,” the budget documents say. “This evolution will integrate the commercial and federal augmentation services with the SCN to create a comprehensive system for automated resource management known as Enterprise Resource Management (ERM). ERM plans to award initial contracts in FY2023 and down-select to a single vendor in FY2024.”

Garcia explained that the long-term vision is to get computer systems for things like scheduling that can function “machine-to-machine” and ease some of the burden on his overtaxed crew. But for now, the mantra at the squadron is making sure everyone who relies on the SCN is aware of its urgent modernization requirements.

“I think what we need to focus on is making sure that everyone across the globe understands that the SCN needs to modernize… and having that that way forward, so that we as the United States maintain our advantage in space. We need to make sure that this keeps up with the risk,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment