Siobhán O'Grady, Isabelle Khurshudyan, Laris Karklis and Samuel Granados

KYIV, Ukraine — The Ukrainian military has spent nearly 15 months exceeding the world’s expectations. Now, senior leaders are trying to lower those hopes, fearing that the outcome of an imminent counteroffensive aimed at turning the tide of the war with Russia may not live up to the hype.

“The expectation from our counteroffensive campaign is overestimated in the world,” Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov said in an interview this past week. “Most people are … waiting for something huge,” he added, which he fears may lead to “emotional disappointment.”

The planned counterattack — made possible by donated Western weapons and training — could mark the most consequential phase of the war, as Ukraine seeks to snatch back significant territory and prove it is worthy of continued support.

Offensive military operations typically require overwhelming advantage, and with Russian forces dug into heavily fortified defenses all across the 900-mile-long front, it is hard to gauge how far Ukraine will get.

The buildup ahead of the assault — the details of which remain secret — has left Ukrainian officials grappling with a difficult question: What outcome will be enough to impress the West, especially Washington?

Some fear that if the Ukrainians fall short, Kyiv may lose international military assistance or face new pressure to engage with Moscow at a negotiating table — not on the battlefield. Such talks would almost certainly involve Russian demands for a negotiated surrender of sovereign territory, which Ukraine has called unacceptable.

“I believe that the more victories we have on the battlefield, frankly, the more people will believe in us, which means we will get more help,” President Volodymyr Zelensky said in an interview Monday with The Washington Post in his heavily fortified headquarters building.

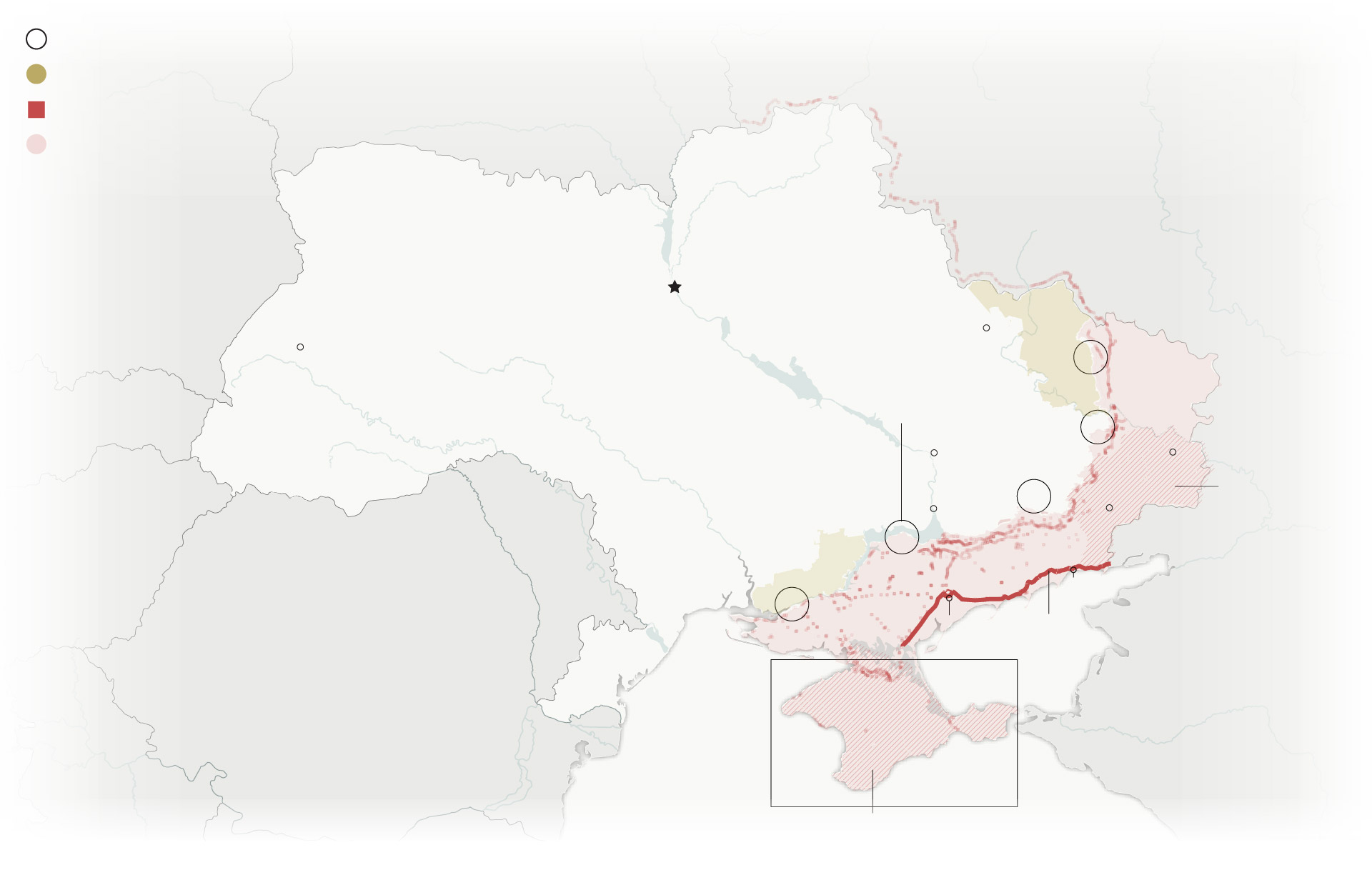

Kyiv is eager to make a rapid breakthrough in what has essentially slowed to a grinding artillery war in the country’s east and south, with neither side making significant territorial gains. Experts say it will be difficult, if not impossible, to push the Russians back to their positions before the invasion started on Feb. 24, 2022, when Moscow held parts of Luhansk and Donetsk and the illegally annexed Crimean Peninsula.

The pressure comes in part from Ukraine’s past battlefield wins — first repelling Russia’s attempt to capture Kyiv and later dislodging the invaders from strongholds in surprise attacks in the Kharkiv and Kherson regions.

“We inspired everywhere because the perception was that we will fall during 72 hours,” Reznikov said. But the track record means Ukraine’s partners now have a “joint expectation that it would be successful again,” he said.

Western partners have told him, he said, that they now need a “next example of a success because we need to show it to our people. … But I cannot tell you what the scale of this success would be. Ten kilometers, 30 kilometers, 100 kilometers, 200 kilometers?”

A major success could rally more support for the Western arms and ammunition Ukraine needs to continue the fight and offer a much-needed morale boost for the civilian population, which relished Ukrainian forces’ resilience against Russia’s efforts to take Kyiv last spring and later their surprise autumn offensive in the Kharkiv region, which retook hundreds of miles of territory in a matter of days.

But in Kharkiv the Ukrainians had an advantage when they stormed Russian troops — who had lowered their defenses — by surprise. Many who remained simply fled without a fight. And in Kherson to the south, Ukraine had a major geographic edge, with Russia struggling to supply troops west of the Dnieper River.

Now, Russia may have the geographic advantage and stronger numbers. Some 500,000 Russian troops are currently focused in Ukraine, with at least 300,000 inside Ukrainian territory, Reznikov said.

Ukraine has 15 functional nuclear reactors, which together supplied 51 percent of its electricity in 2020. Six of those reactors are at the Zaporizhzhia plant, the largest facility of its kind in Europe. It has been under Russian control since March 4, 2022.

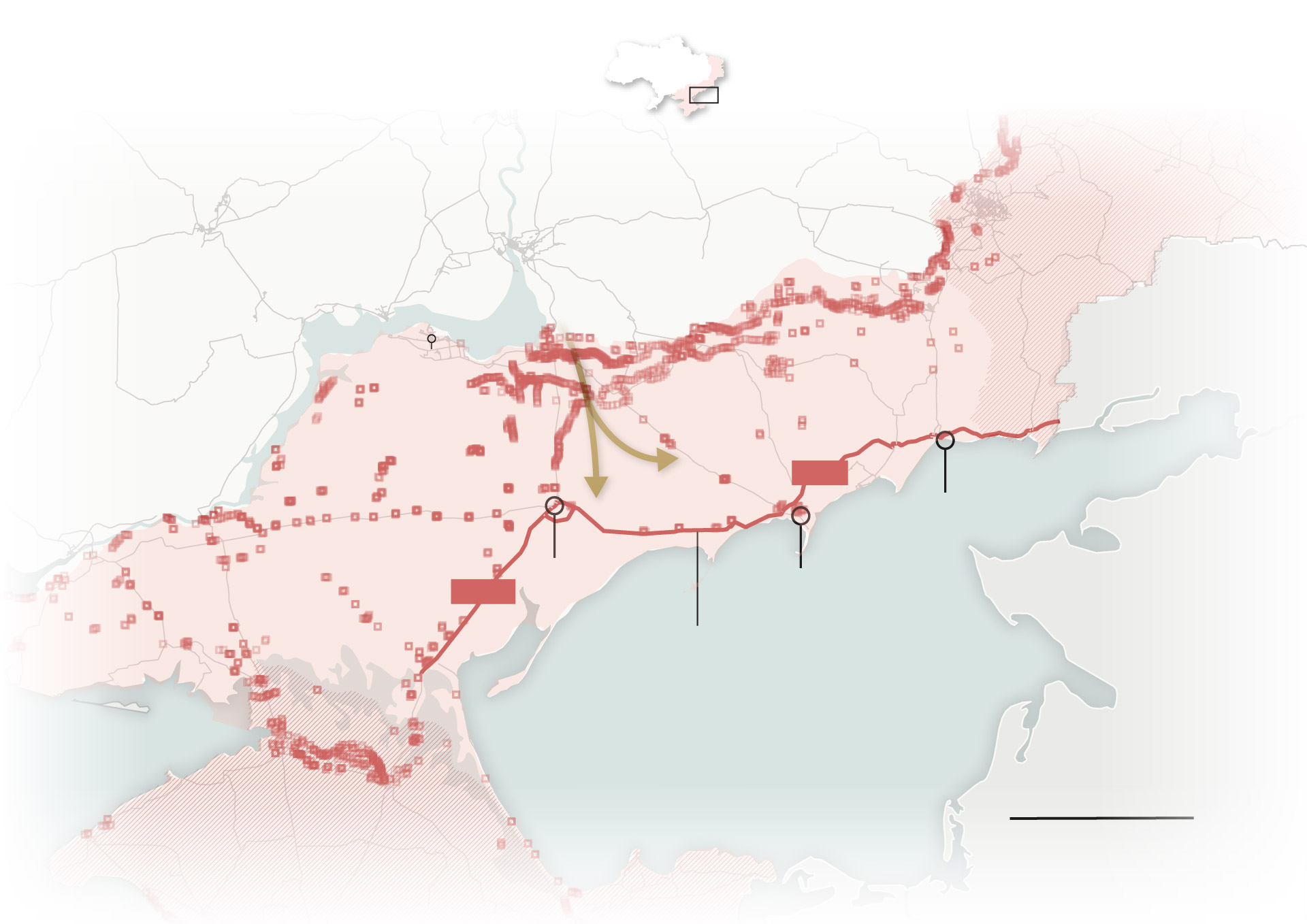

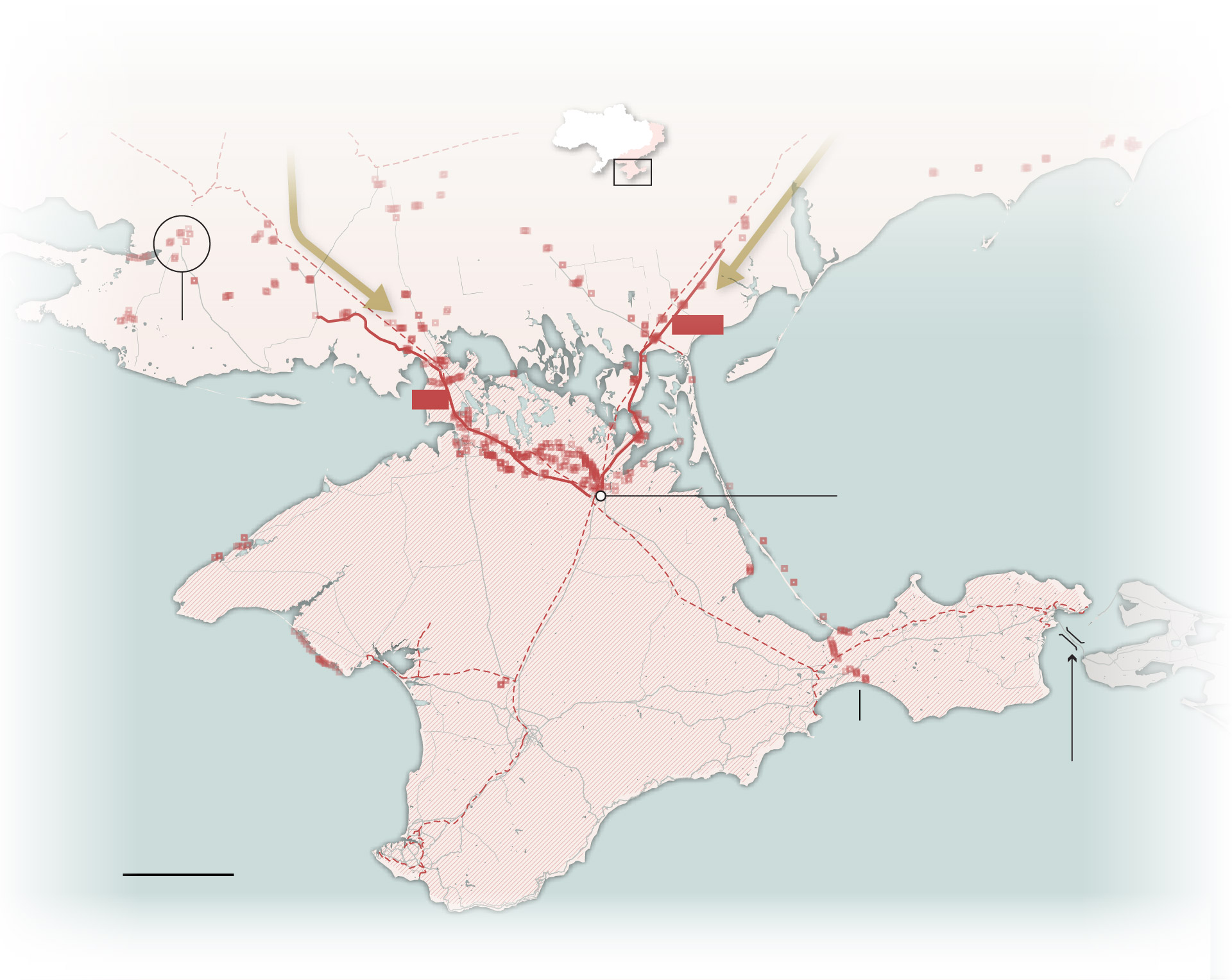

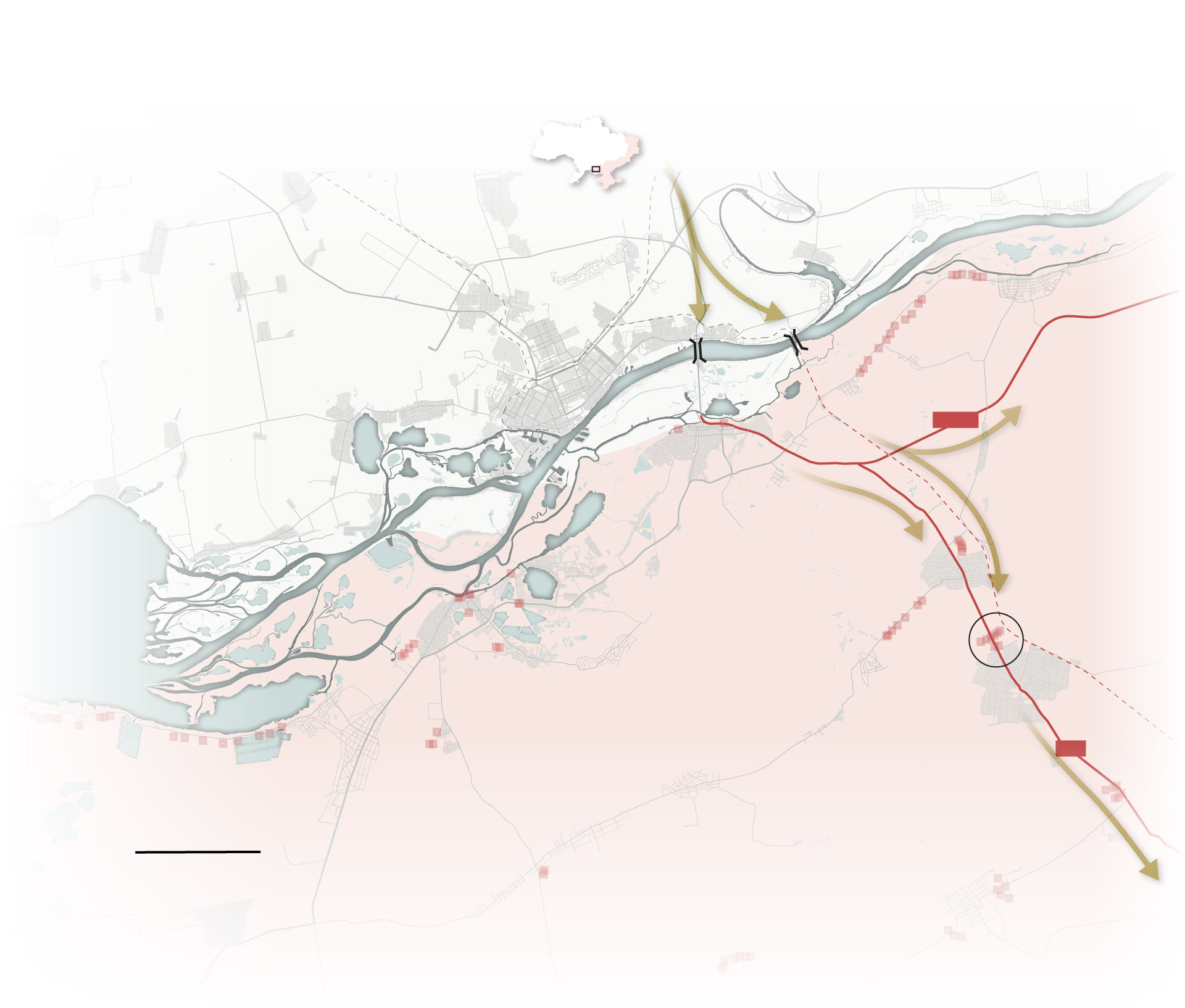

One key objective for Ukraine, and perhaps an early sign of success, would be to break the so-called land bridge between mainland Russia and occupied Crimea, severing crucial supply lines to Russian troops in the Zaporizhzhia region, and isolating Russian bases on the peninsula.

Another top imperative is to regain control over hugely valuable critical infrastructure facilities, including the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, Europe’s largest atomic energy station, which is located in the occupied city of Enerhodar, and the Kakhovka hydroelectric plant in the southern Kherson region.

Recognizing the formidable obstacles, Ukrainian officials have continued to press for additional materiel from supporters in the West.

Ukraine will be ready to launch the assault “as soon as the weapons that were agreed with our partners are filled,” Zelensky said. The timeline could also depend on weather, because of unseasonably damp ground along the country’s front lines.

Reznikov said that Ukraine’s “first assault formation” is more than 90 percent prepared to begin but that some designated troops are still finishing training programs abroad.

The huge front line creates numerous potential avenues of attack.

Ukraine could focus its efforts south and attempt to seize the city of Melitopol, which Russia has established as the occupied regional capital of Zaporizhzhia, and then push forward in an effort to sever the land bridge.

Ukraine could also attack Crimea itself, probably with naval operations and possibly even beach landings. Satellite imagery shows extensive trenches that Russian forces have dug in preparation for a potential assault.

Other scenarios could see the Ukrainians attacking east through the fiercely embattled city of Bakhmut, or from the town of Kupiansk, in a push to regain control of areas in the Luhansk region.

Yevgeniy Prigozhin, the founder of Russia’s Wagner mercenary group, has threatened to withdraw his forces from Bakhmut, which would leave the city vulnerable. Another option would be for the Ukrainians to attack Russian positions through the southern city of Vuhledar toward occupied Mariupol on the Sea of Azov.

Zelensky said he would consider reoccupying any Ukrainian territory to be “a success.”

“I can’t tell you which towns or cities, which borders are a significant success for us and which are average … only because I don’t want to prepare Russia for how, in which directions, and where and when we will be,” he said.

Ideally, Reznikov said, the offensive will not only liberate villages and cities but also “cut logistic chains of [Russian] troops” and “reduce their offensive capacity.”

Western leaders insist Ukraine is well-equipped for the fight ahead.

But U.S. intelligence assessments disclosed in a massive leak of classified documents on the Discord forum revealed U.S. misgivings about Ukraine’s ability to make major progress this spring, in part due to assessed “deficiencies in training and munitions supplies.”

“We are currently losing in the sky,” Zelensky said in the interview with The Post in Kyiv. The Ukrainian president has been pleading for American-made F-16s. President Biden has pointedly denied the request, saying Zelensky does not need the planes.

Zelensky said that Ukraine will not wait for more fighter jets to start the offensive but that “it would be much easier for us” if they had them.

And although Ukraine recently received the U.S.-made Patriot missile-defense system, “we also need to remember that the name alone does not protect people,” Zelensky said.

More air defense is “priority number one,” Reznikov said.

Gen. Richard Barrons, commander of the U.K. Joint Forces Command from 2013 to 2016, said there are concerns that Ukraine’s still-depleted air defenses could face a barrage from Russian missiles once the counteroffensive begins.

The United States, he said, might have to strip its own systems in order to counter the weakness. “There is a question mark over Ukraine’s ability to control its own airspace,” Barrons said, adding that it had been a clear Russian tactic throughout winter to try to exhaust Ukrainian air defenses, which had mostly consisted of Russian or Soviet-made equipment.

Ukraine is also pleading for more long-range strike capabilities as the counteroffensive nears its start. Kyiv’s partners have long expressed fears that such equipment could be used to strike inside Russia — potentially triggering a major escalation from Moscow. But the lack of such weaponry is putting Ukraine at a serious disadvantage, Zelensky said.

“I don’t quite understand, I’ll tell you frankly, why we can’t get long-range artillery,” he said, contending he has offered assurances that Ukraine would not use such equipment to strike inside Russia, as some allies fear.

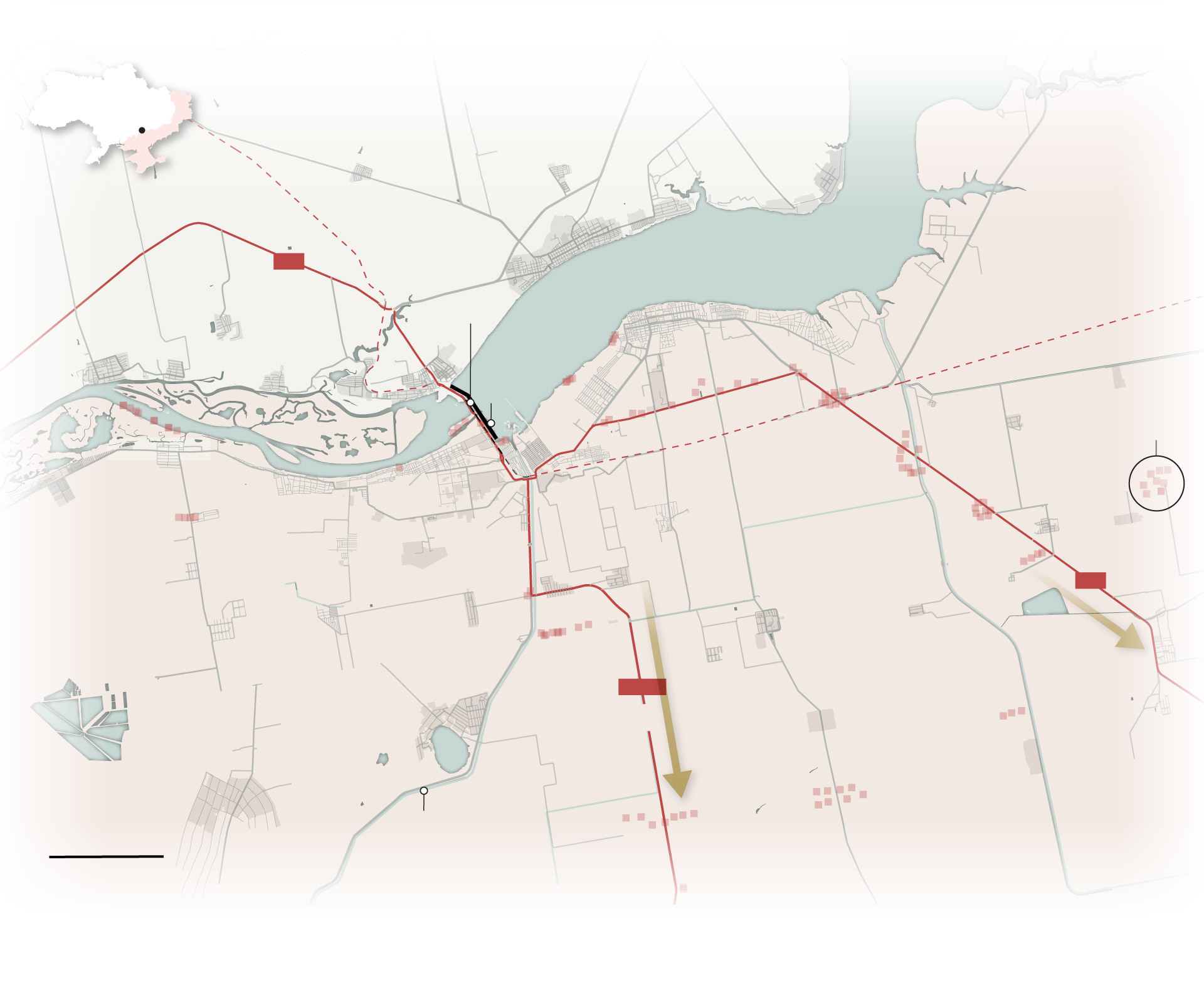

This lack of equipment, Zelensky said, is why Ukrainian forces, after retaking the southern city of Kherson in November, have been unable to push Russian forces out of the territory they control just across the Dnieper River.

It’s from those riverside positions that Russian forces regularly lob ammunition into the now Ukrainian-controlled city. Dozens of civilians have been killed in such shelling in the months since Kherson’s liberation.

“They can take troops from there and move them to the east or to the south. And still, they are reinforcing,” Zelensky said. “Why? Because they know that we cannot reach them … and we suffer every day because they have the ability to shoot at our people.”

Russian forces in Kherson knew that Ukraine lacked long-distance strike capabilities, so “they withdrew all their command posts, fuel depots, ammunition depots, more than 120 kilometers away,” Reznikov said.

“That’s why we need something interesting with a range capability of 150 kilometers,” he said. “It’s become more difficult for them logistically. But we need to push them deeper and deeper.”

Sources: Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project, OpenstreetMap, Openinframap. Brady Africk, who analyzed satellite imagery from Copernicus Open Access Hub, provided fortifications data, which does not include all fortifications in Ukraine; some defenses predate Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Karklis reported from Washington and Granados from Malaga, Spain. Catherine Belton in London contributed to this report.

One year of Russia’s war in Ukraine

Portraits of Ukraine: Every Ukrainian’s life has changed since Russia launched its full-scale invasion one year ago — in ways both big and small. They have learned to survive and support each other under extreme circumstances, in bomb shelters and hospitals, destroyed apartment complexes and ruined marketplaces. Scroll through portraits of Ukrainians reflecting on a year of loss, resilience and fear.

Battle of attrition: Over the past year, the war has morphed from a multi-front invasion that included Kyiv in the north to a conflict of attrition largely concentrated along an expanse of territory in the east and south. Follow the 600-mile front line between Ukrainian and Russian forces and take a look at where the fighting has been concentrated.

A year of living apart: Russia’s invasion, coupled with Ukraine’s martial law preventing fighting-age men from leaving the country, has forced agonizing decisions for millions of Ukrainian families about how to balance safety, duty and love, with once-intertwined lives having become unrecognizable. Here’s what a train station full of goodbyes looked like last year.

Deepening global divides: President Biden has trumpeted the reinvigorated Western alliance forged during the war as a “global coalition,” but a closer look suggests the world is far from united on issues raised by the Ukraine war. Evidence abounds that the effort to isolate Putin has failed and that sanctions haven’t stopped Russia, thanks to its oil and gas exports.

No comments:

Post a Comment