Carlos Roa

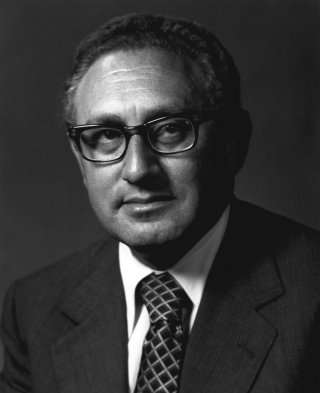

Today—May 27, 2023—marks the 100th birthday of Henry A. Kissinger, one of America’s most influential and famous foreign policy minds (and Honorary Chairman of The National Interest). In commemoration of this date, The National Interest will be rerunning some of our best content on Kissinger throughout the day.

It is likewise worth spending a moment contemplating Kissinger himself on this occasion, for in the annals of American diplomatic history, few figures command such awe, inspire such debate, or embody such complexity.

A refugee from Nazi Germany, Kissinger’s life and career embody a particularly American tradition: triumphing over adversity, working service to a new homeland, and relentless intellectual engagement with the challenges of one’s era. Rising from relative obscurity to the zenith of American power, his trajectory embodied the promise of the American Dream, even as his approach to international relations was grounded in a deeply pragmatic and realist worldview.

Kissinger’s approach to foreign policy—realpolitik—is defined by a clear-eyed understanding of the world as it is, rather than as we might wish it to be. Power, balance, negotiation—these were his instruments. He sought not to reshape the world in America’s image, but to manage it, to balance its forces, and thus secure the national interest. This approach won him both admirers and detractors. To his supporters, this sort of pragmatism is a breath of fresh air in a world full of ideological crusades. To his critics, his approach is a chilling dismissal of human rights, if not worse.

But Kissinger’s accomplishments as Secretary of State and National Security Advisor speak for him. He laid the groundwork for détente with the Soviet Union, pursued a policy of engagement with China that profoundly reshaped the global order, and sought a lasting peace in the Middle East with the historic shuttle diplomacy after the Yom Kippur War. His negotiation of the Paris Peace Accords, for all their imperfections, helped bring an end to U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

As we commemorate this milestone, it is worth reflecting on the challenges that lie ahead. The lessons of Kissinger’s realpolitik—both its successes and its failures—remain profoundly relevant. A devoted student of history, Kissinger emphasizes the necessity of a stable world—one where great powers must be balanced, where economic forces shape diplomacy, and where statesmen must be able—as Kissinger himself wrote so eloquently in his doctoral dissertation—“to contemplate an abyss, not with the detachment of a scientist, but as a challenge to overcome—or perish in the process.”

Contemporary policymakers must take heed, lest the apocalyptic century of a hundred years ago repeat itself. As U.S. preponderance fades and a multipolar order takes its place, America will need leaders capable of guiding her through this new age. Kissinger’s legacy is a timely reminder that the conduct of foreign policy is a delicate balancing act, one that requires both wisdom and will, as well as an understanding of the world as it is, even as we labor to make it as it ought to be.

No comments:

Post a Comment