Catherine Putz

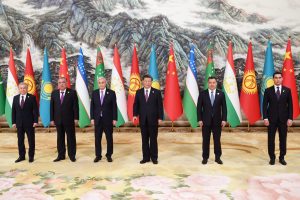

Chinese leader Xi Jinping and the leaders of Central Asia — Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon, Turkmen President Serdar Berdymuhamedov, and Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev — gathered for the first time in person (although it is the third China-Central Asia summit since the format was kicked off in 2020) in Xi’an, a city in Shaanxi Province known historically as Chang’an.

Chang’an marked the eastern end of the ancient Silk Road.

To hear Xi tell it, the Silk Road has contemporary corollaries: the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Highway, the China-Tajikistan Highway, the China-Kazakhstan oil pipeline, and the China-Central Asia natural gas pipeline are today’s “Silk Roads” and freight trains and non-stop flights are “contemporary camel teams.”

Before the summit, Beijing promised a “new blueprint” for relations between China and Central Asia, but at best that was an exaggeration. The summit produced the clearest iteration yet of Chinese ambitions and commitments to engagement in Central Asia, but very little is new.

Last year, when Xi and the Central Asian presidents marked 30 years of relations they announced the building of a “China-Central Asian community with a shared future,” a regional twist on the Chinese diplomatic catchphrase of creating a “community with a shared future for mankind.” Xi outlined four core principles in that effort during his keynote speech at the summit.

The first point — phrased as “protecting and helping each other” — stressed the importance of deepening “strategic mutual trust” and giving support “on issues related to core interests such as sovereignty, independence, national dignity, and long-term development…” Next, Xi highlighted the need to adhere to “common development” under the auspices of the Belt and Road Initiative. A third principle related to upholding “universal security” via joint implementation of the Global Security Initiative and common Central Asia-centric themes of opposing “external forces” trying to instigate “color revolutions” and together opposing the “three evil forces.” Finally, Xi highlighted “everlasting friendship” and building a solid foundation for the future of close ties across generations.

Xi also tacked on a eight-point list of efforts to develop China-Central Asia cooperation, including institution building, economic and trade relations, connectivity, energy cooperation, green innovation, development, “dialogue among civilizations,” and maintaining regional peace.

After the summit, the gathered leaders released a joint statement, the China-Central Asia Xi’an declaration. The declaration’s 15 points together construct a vision of strong and growing ties between China and the states of Central Asia. The first point, for example, reads in part: “Faced with major changes unseen in a century, and focusing on the future of the people in the region, the six countries are determined to join hands to build a closer China-Central Asia community with a shared future.”

The Chinese and Central Asian leaders agreed to formalize their summits, to be held every two years and alternating between China and the Central Asian states. Kazakhstan will host the next meeting in 2025.

A point geopolitical analysis will likely focus on is the reaffirmation enshrined in the declaration of “mutual understanding and support on issues concerning each other’s core interests.” On China’s side, the declaration states that Beijing “firmly supports the development path chosen by the Central Asian countries, and supports all countries in safeguarding national independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity and adopting various independent domestic and foreign policies.” On Central Asia’s side, the Chinese Community Party’s “valuable experience… in governing” is acknowledged, as is the “significance of the Chinese-style modernization path to the development of the world.”

The declaration, from there on, touches on the major spheres of cooperation between Central Asia and China, many of them related to economics and trade or energy, but with sections focused on climate change, green energy, advanced technology, and cultural links.

There is much more to unpack from the China-Central Asia Summit, especially stemming from the various bilateral visits that occurred on the sidelines. (I’ll write more about that in the upcoming Diplomat Magazine issue.) But as in my preview of this summit, I want to note the timing and geopolitical currents swirling around. The China-Central Asia Summit overlaps with the first day of the G-7 Summit in Hiroshima, Japan — a gathering of the world’s top industrialized democracies (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States) and their friends, importantly including Ukraine this year. Russia, until 2014 part of what was then the G-8, will surely be a topic of discussion in Japan during the summit, where further commitments to supporting Ukraine are expected.

Some will read the China-Central Asia Xi’an Declaration’s reference to “national independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity” as a jab at Russia, but it would be difficult to imagine such a declaration — made by China or the Central Asian states — without those words. Russia was not directly mentioned during the China-Central Asia Summit, nor was the war in Ukraine, but Russia’s influence and importance in Central Asia looms large.

China’s may loom larger in the future.

And a final note: In his keynote speech Xi opened by harkening back to ancient times, to the Silk Road that stitched China and Central Asia together. His referencing a Tang Dynasty poet was perhaps unintentionally ironic. It was during the Tang Dynasty that Chinese expansion westward was halted in Central Asia at the battle of Talas in 751. It’s clear from the recent summit that Chinese expansion westward may have been delayed by centuries, but has not been denied.

No comments:

Post a Comment