Clifford D. May

Is France still an ally of the United States? Based on Emmanuel Macron’s three-day state visit to the People’s Republic of China earlier this month, the answer to that question is in doubt.

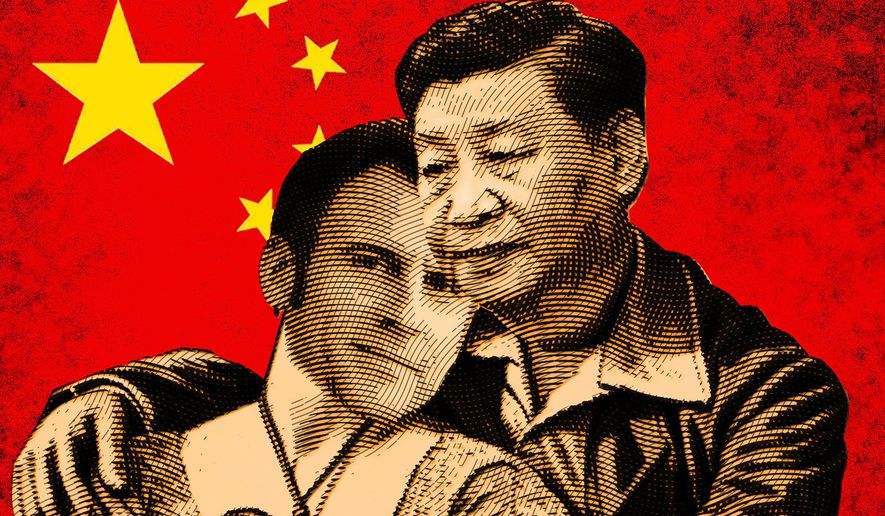

To say that the French president kowtowed to Xi Jinping, the most powerful Chinese ruler since Mao Zedong, would be to exaggerate — but not by much.

Alluding to Mr. Xi’s intention to displace the U.S. as a global leader, Mr. Macron reportedly told Mr. Xi that “France does not pick sides.”

The new international order Mr. Xi envisions would be based on rules made by the Chinese Communist Party. Apparently, that troubles Mr. Macron not at all.

What does? In an interview with journalists from Politico and Les Echos, a French financial newspaper, Mr. Macron warned against Europe becoming “America’s vassal.” He urged his fellow Europeans to seek “strategic autonomy,” and to avoid “getting caught up in crises that are not ours.”

Accompanying Mr. Macron to China were several dozen French tycoons. In their briefcases were contracts they were eager to have signed by Chinese businessmen or CCP leaders — a distinction without a difference if you understand Beijing’s strategy of “military-civil fusion.”

As far as we know, Mr. Macron did not raise thorny issues such as Beijing’s cover-up of the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic, its persecution of Uyghurs, Tibetans and other minorities, or its crushing of Hong Kong’s freedoms in blatant violation of treaty obligations.

Nor did Mr. Macron suggest that French relations with the People’s Republic would suffer should Chinese troops invade Taiwan. Given that “Europeans cannot resolve the crisis in Ukraine,” he said, “how can we credibly say on Taiwan, ‘watch out, if you do something wrong we will be there’?”

At the conclusion of the visit, a 51-point joint declaration announced France’s “global strategic partnership with China.” That sounds like an alliance, don’t you think?

Mr. Macron also told reporters — this he’s said previously — that he wants Europe to become a “third superpower.” To achieve that goal would surely require significantly increased defense expenditures. That seems unlikely considering that many of Europe’s NATO members have never allocated even 2% of gross domestic product to defense — despite having repeatedly pledged to do so.

Nor did Mr. Macron reflect on the irony that less than a year ago, he withdrew French military forces from Mali, one of many former French colonies with which Paris had long maintained a “special relationship.”

Those troops — first deployed to the West African country nine years ago at the invitation of the Malian government to combat jihadis linked to al Qaeda and the Islamic State — have now been replaced by Russian forces, including Wagner Group mercenaries infamous for ignoring the laws of armed conflict.

Since assuming office in 2017, Mr. Macron has not been a particularly effective French leader. Nor is he currently a popular one. A poll this month finds his support down to just 26%.

One issue driving dissatisfaction is his push for pension reform — raising the retirement age from 62 to 64. Frenchmen furious at the prospect of having to wait so long to take to their rocking chairs have nevertheless summoned sufficient energy to stage mass and sometimes violent protests.

One of Mr. Macron’s goals in Beijing was to persuade Mr. Xi to use his influence to end Russia’s war against Ukraine. He failed. The joint declaration I mentioned above neither condemned Russian aggression nor mentioned Beijing using its influence to rein in Vladimir Putin.

Mr. Macron made other — undoubtedly worse — statements concerning Taiwan and “strategic autonomy” on his visit to China. We know that because officials at the Elysee, the palace where French presidents reside, instructed Politico and Les Echos not to include them in their reports. (Abiding by such instructions was a condition for granting the interview.)

The Elysee then issued a statement asserting that France “is not equidistant between the United States and China. The United States is our ally, with shared values.”

Convinced?

Last Friday, China’s ambassador to France remarked that Ukraine and other independent nations that were once part of the Soviet empire may not be independent states in Beijing’s eyes because “there’s no international accord to concretize their status as a sovereign country.” Did he say that to embarrass Mr. Macron? Is Mr. Macron embarrassed (as he should be)?

The more things change, the more they remain the same, as the French say. Back in 1990, after spending three years as The New York Times’ correspondent and bureau chief in Paris, Richard Bernstein wrote “Fragile Glory: A Portrait of France and the French,” a marvelous book judiciously combining admiration and criticism.

He observed that the French, across the political spectrum, cling to the idea that their nation is “a beacon of illumination to the rest of the world.” He quoted Charles de Gaulle, who — despite the “humiliation and shame of defeat in World War II” — insisted: “France cannot be France without grandeur.”

Grandeur could be achieved, de Gaulle believed, by making France the leader of what Mr. Bernstein called “a third great power bloc in the world buffering the Soviet-American antagonism.”

It appears Mr. Macron is recycling that aspiration, imagining France buffering what he sees as the Sino-American antagonism.

French wines age well. Gaullist ideas, not so much.

What we once called the free world currently faces more formidable adversaries than during the Cold War. Some European leaders are clear-eyed about the threat posed by the imperial ambitions of Beijing and its partners in Moscow, Tehran, and other capitals of unfree nations.

Those leaders would be well advised to sit down with Mr. Macron and explain why an alliance with the U.S., for all its flaws, remains preferable to the alternatives.

• Clifford D. May is founder and president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) and a columnist for The Washington Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment