NOAH SMITH

I think we’re about due for another update on the China decoupling situation. Decoupling isn’t just a geopolitical or military thing; it’s going to be one of the most important economic trends of the next couple of decades. In other words, whether you’re trying to make money or make policy, it’s something you probably need to follow.

First, let’s talk about what “decoupling” does and doesn’t mean. When some people hear “decoupling”, they think of an Iron Curtain type situation — a world carved into two separate and distinct trading blocs, one led by China and the other led by the developed democracies, each of which trades with each other but not with the other bloc. While I do think something like this is a possibility in the long term, I would be surprised if it happens in the short term. You can see in the trade numbers that we’re not even really headed in this direction yet; Chinese exporters may have lost a bit of profitability, but U.S.-China trade hit an all-time high in 2022.

Where decoupling is likely to happen, and soon, is in the world of investment. In the old economic system of the 2000s and the 2010s, the corporations of the developed democracies made things in China and then sold those things back to the big markets of the developed democracies. That meant they had to invest in China, by building factories and offices there. It’s this system of investment that’s breaking down, and that I expect to break down further.

Investment decoupling has been happening for a while now

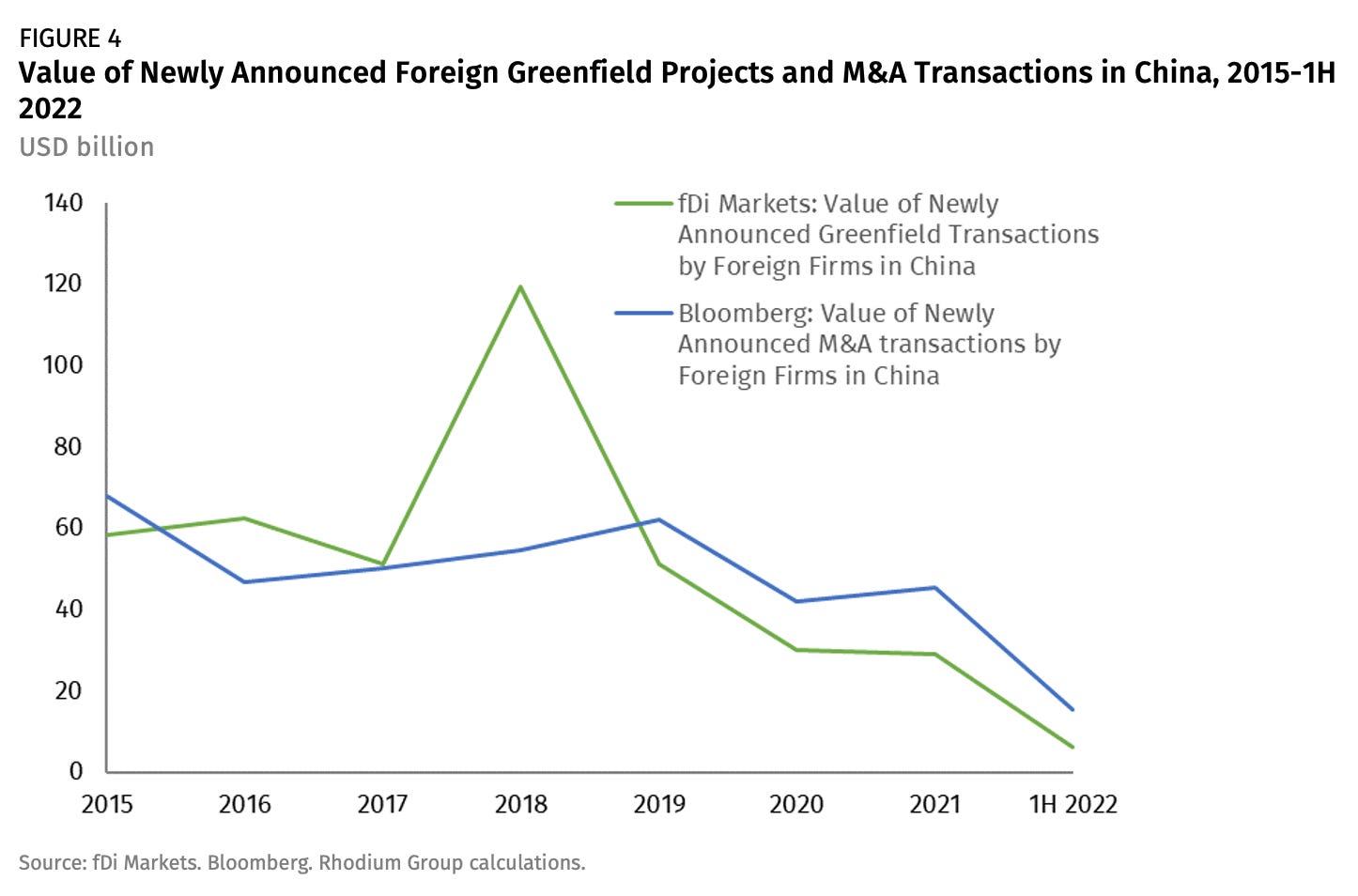

In fact, this is not a very bold prediction on my part; it’s already happening. As a percent of China’s GDP, foreign direct investment is down from 4% of China’s GDP in 2011 to just 1% today, and in total dollar terms it has fallen from $300 billion to around $200 billion. And in addition we always have to remember that a lot of “FDI” into China is fake; it’s just Chinese companies investing in China via Hong Kong. When you look at FDI from the developed democracies, the drop in recent years is even starker. FDI from the G7 was $35.3 billion in 2014, but only $16.3 billion by 2020 — and that was before the gigantic drop in 2022. If you look at “greenfield” investment — where a company decides to build some new factories or offices in China — the drop is even more dramatic:

Source: Rhodium Group

That’s from a Rhodium Group report from 2022, by the way, which has much more data on this topic.

This should tell you two things. First of all, my prediction of investment decoupling is really just a “more of the same” forecast. And second, decoupling has been happening for a while now, since before war tensions, before export controls, before Covid, and before Trump’s tariffs. That suggests that there are deeper forces at work here; the old global economic system based around outsourcing production to China had deep contradictions that were always going to surface at some point. I don’t want to go over the whole list in detail again, but basically the reasons were:

China used FDI as an opportunity to steal multinationals’ technology and transfer it to state-supported domestic competitors, thus making FDI into China a bad deal for many multinationals

China understandably didn’t feel like being a low-value production base for foreign companies forever, and instead wanted to climb up the value chain by making components and doing branding

Chinese costs increased as the country got richer, until the “China price” was no longer competitive

But that’s all old news. What I want to talk about today is why investment decoupling is going to continue, and maybe even to accelerate.

There seems to be a general idea out there that decoupling is being fundamentally driven by U.S. and European policy. That view is extremely incomplete. Yes, export controls and investment restrictions are important policies, and friend-shoring incentives might now be having a bit of an effect. But much of the impetus from decoupling is coming from two other sources: Chinese policy, and the rational calculations of multinational companies themselves.

Once we understand that, it’s clear why continued decoupling is by far the likeliest outcome.

Decoupling is a side effect of China’s political goals

I guess some people think that because China grew very rapidly under the old “Chimerica” system, that this system was to their benefit and they’d never want to change it. But in fact they have several reasons for wanting a change.

The first, as I said, is that owning your own brands, instead of making stuff for foreign brands, gets your country a lot more money. So given the choice, China would rather make BYD cars instead of Tesla cars, Hisense TVs instead of Samsung TVs, and Huawei phones instead of Apple iPhones (good luck with that last one). What this means is that after China is already done harvesting as much technology from a multinational as it can, the government will see little problem in making life progressively harder for that multinational. Here are a couple of examples from recent weeks:

As well as changes to its espionage law, China in recent weeks spooked foreign executives by questioning staff at consulting firm Bain & Co.’s Shanghai office, launching a cybersecurity review of imports from chip maker Micron Technology, and detaining an executive of Japanese drugmaker Astellas Pharma.

But an even bigger reason that China wants decoupling is just the increasing xenophobia and paranoia of the Xi Jinping regime. Xi’s predecessors did indeed see FDI as more of an opportunity than a threat, and even Xi himself did in the early years of his rule. But in the last few years, as international tensions have mounted and the country has faced an economic slowdown and the specter of domestic unrest, Xi has decided that many of the essential features necessary to create an economy that encourages FDI are no longer worth the “cost” in terms of societal openness.

A vivid example is China’s closure of its information ecosystem. The government has rapidly decreased the amount of macroeconomic data it publishes. Now it’s restricting access to information about Chinese companies as well:

Prodded by President Xi Jinping’s emphasis on national security, authorities in recent months have restricted or outright cut off overseas access to various databases involving corporate-registration information, patents, procurement documents, academic journals and official statistical yearbooks.

Of extra concern in recent days: Access to one of the most crucial databases on China, Shanghai-based Wind Information Co., whose economic and financial data are widely used by analysts and investors both inside and outside the country, appears to be drying up…

Here’s a good interview with WSJ reporter Lingling Wei, who has covered the information blackout. A couple excerpts:

[China’s leaders] are really emphasizing the need to keep and welcome foreign capital. However, their actions really run counter to this rhetoric…One big driver is the Chinese leadership’s need to control the narrative about China…[A]ll those foreign think tanks, foreign research firms have written too many negative reports to “smear” China.

So that really helps explain why they’re trying to crack down on some of those firms now. They want the Party to have the monopoly on how the rest of the world forms opinions about China. It’s very important, it’s not just about propaganda or PR; to the Party, it’s an issue of survival…

Obviously it takes time to see the actual impact on money flows, investment flows. But people certainly are spooked, American and other foreign companies, and local employees on the ground in China.

If you can’t get good data on local economic conditions or market conditions, investing in a country becomes a lot harder.

Nor is the U.S. the only target. Here is a report detailing numerous examples of China attempting to threaten European, Korean, and Japanese companies for a variety of nationalistic or geopolitical reasons. These companies sometimes respond by submitting to China’s wishes, but more often they just begin to question the wisdom of continuing to invest in China.

Taken together, all these moves send a powerful signal that China is no longer “open for business” in the way it was in earlier decades, and that many of the multinational investors with factories and offices in the country are basically living on borrowed time. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce released a statement declaring that recent Chinese moves have “dramatically increase[d] the uncertainties and risks of doing business in the People's Republic.”

So that’s going to give decoupling a big push.

Decoupling really is “de-risking”

A second big push, I think, is going to come from international tensions. The U.S. government has been very eager, in recent months, to downplay the term “decoupling” in favor of “de-risking”. This isn’t just a rhetorical move designed to make the U.S. look less economically bellicose — it’s a way of focusing attention on the fact that disinvestment from China is a way of reducing a company’s existential risk.

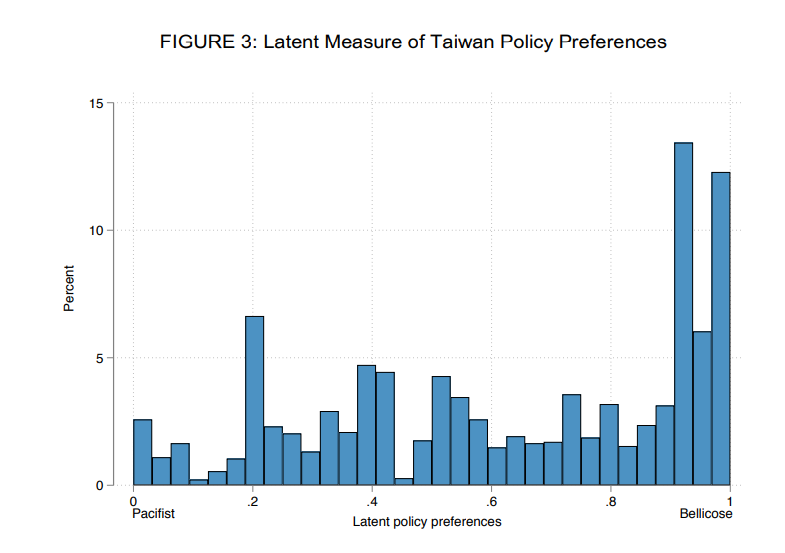

Risk of war over Taiwan is increasing. Contrary to the people who think this risk is coming mainly from the United States, there is rising appetite for war among both the Chinese political class and the general citizenry. According to a recent paper by Adam Liu and Xiaojun Li assessing survey data from 2020-21, a pretty solid majority of Chinese people would find full-scale war with Taiwan “acceptable”, and a substantial minority are eager for a fight.

Source: Liu & Li (2023)

Source: Liu & Li (2023)

Meanwhile, a recent article by Tong Zhao in Foreign Affairs warns that China’s political class has become something of a hawkish echo chamber on the Taiwan question.

Now, imagine you’re the executive of a U.S. company considering whether to put your factories and offices in China (or keep them in China). You see these numbers and read these articles and you realize that the risk of a war over Taiwan is not particularly low. Your next realization will probably be that all of your investments in China will be in extreme danger of being utterly vaporized on the day that the balloon goes up.

In that scenario, the very best outcome is that you’ll be unable to work with your factories and offices in China due to a communications blackout, and that you’ll face substantially more challenging conditions in China once the conflict end, including not being able to liquidate your investments and get your money out of the country due to capital controls.

A worse outcome — which seems not unreasonable, given China’s various other moves and general approach — is that your factories and offices in China will be abruptly nationalized, picked over for intel by the Chinese security services, and asset-stripped. (The worst-case outcome, of course, is World War 3.)

Given that imminent and existential risk to your China business, why would you keep your factories and offices in China? Maybe you’ve bought the line that the U.S. is driving all the tensions, and maybe you can call up your friends in Washington and get them to stop doing whatever it is you think they’re doing to provoke China. Well, if so, you’re in for a rude awakening when you discover that it’s China driving the increased tensions, and there’s not a lot we can do to reduce tensions short of guaranteeing that we definitely won’t come to Taiwan’s aid in the event of a Chinese invasion (a guarantee that we are highly unlikely to offer).

If you’re a smart and perceptive executive, you will realize that betting big on China as a production platform for your international sales is a pretty dangerous play. One way to manage your risk would be to keep making things in China for the Chinese market, but move your production for the non-Chinese market out of China. This is what Dan Wang suggested in our recent interview:

Well, the way to thread the needle is to continue producing goods in China for the large and possibly still growing market. At the same time, firms are trying to move the export-bound production from China to countries like Vietnam, India, and Mexico. I expect that in a decade we won't see that China makes 90% of the world's iPhones, for example, while making up around 20% of its market.

The Rhodium Group agrees, writing that “large greenfield investments by established foreign players for local consumption [have] become an increasingly important driver of FDI in China.”

Of course the country most affected by this risk is Taiwan itself. Taiwan is small, but it’s very high-tech, and its investment and technological expertise have been especially important for China. So the fact that Taiwanese businesses are now looking around frantically for somewhere to invest other than China is significant.

The upshot: Decoupling is going to continue

So beyond policies in the developed democracies aimed at forcing decoupling, a lot is just going to happen on its own, due to a combination of China’s increasingly unfriendly business climate and the increasingly obvious risk of assets in China vaporizing in the event of a war. And if I’m right about that, it will represent not a clean or sudden break with the past, but a continuation of a decoupling trend that has been in evidence for about a decade, for those who cared to look.

So where will the investment go? A bunch of different places, but a few general trends are already fairly clear:

Labor-intensive manufacturing, especially in the electronics industry, will go mostly to low-cost developing countries in the Asian electronics supercluster — Vietnam, India, Indonesia, etc.

Heavier stuff like parts for machinery and autos and aircraft will shift to places like Mexico and East Europe that are close to the U.S. and European markets, in addition to low-cost and mid-cost countries in Asia.

High-tech electronics activities like semiconductor and display manufacturing will go to advanced economies like Japan and South Korea — especially Japan, given that out of all the rich East Asian countries it’s the least exposed to imminent invasion.

Some might even go to U.S., if we can make the tough political decision to actually build factories and hire the foreign workers necessary to teach us how to operate them, instead of writing big checks for things that never get built, insisting on multi-year environmental reviews enforced by multi-year lawsuits, and keeping out foreign workers under the false premise that they pose a threat to locals.

But wherever the investment goes, the clear fact is that the old world where China was a push-button, no-brainer destination for corporate investment is being swept away.

No comments:

Post a Comment