Sergey Sukhankin

Executive SummaryChina`s strategic interests in Sub-Saharan Africa are diverse and, while still being primarily guided by the need to maintain access to locally extracted raw materials, now go beyond this goal. In fact, growing investments in infrastructure, manufacturing and green energy are likely to see greater involvement from Chinese state-owned enterprises in Africa. This will undoubtedly demand a greater level of protection for China’s material assets and personnel, given the myriad of security risks throughout Africa.

As one of the means to protect the lives of its employees and material assets, Beijing might increase the use of private security companies (PSCs) in Africa. Yet, certain internal factors (objective weakness of Chinese PSCs and some gaps in domestic legislation) and external conditions (African stance on foreign PSCs) might restrict or limit the use of these groups in Africa.

China will approach the use of PSCs in Africa—where it has been able to build a positive image as an actor relying on “soft power” and trade—with a great deal of caution, lest it sours its image as a responsible great power.

In some countries of Anglophone Africa—especially those that are small and greatly indebted—China may attempt to experiment with a blend of state and private (which in the Chinese context is a murky term) forms of security involvement in certain countries as a means to protect its nationals and assets.

Starting from the launch of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, China has increased its presence in Africa. Beijing’s strategic interests in Africa are premised on four main pillars: (1) the continent`s endowment with practically all natural resources that are critical to Chinese economic growth and development; (2) access to African consumers, which helps China diversify its exports; (3) a young population, which would allow China to transfer some elements of its production cycle to Africa at a fraction of the cost otherwise spent on domestic workers; and (4) the geopolitical aspect, in which Beijing views African countries—or rather their voting power in the United Nations and other international organizations—as allies in legitimizing some of its actions on the international stage. Thus, as it was correctly pointed out in the 2020 US-China Economic and Security Review Commission Report to Congress:

Beijing has long viewed African countries as occupying a central position in its efforts to increase China’s global influence and revise the international order. Over the last two decades, and especially under General Secretary Xi’s leadership since 2012, Beijing has launched new initiatives to transform Africa into a testing ground for the export of its governance system of state-led economic growth under one-party, authoritarian rule. Beijing uses its influence in Africa to gain preferential access to Africa’s natural resources, open up markets for Chinese exports, and enlist African support for Chinese diplomatic priorities on and beyond the continent.[1]

An equally important statement on the subject was produced by Stephen J. Townsend, former commander of United States Africa Command, who said, “Our [i.e., US] competitors clearly see Africa’s rich potential. Russia and China both seek to convert soft and hard power investments into political influence, strategic access, and military advantage. China’s economic and diplomatic engagements allow it to buttress autocracies and change international norms in a patient effort to claim their second continent.”[2]

As such, this report considers the activities of Chinese PSCs in Anglophone Africa, which includes five countries in West Africa (Gambia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, as well as part of Cameroon), South Sudan and areas in Southern Africa (South African Republic) and the African Great Lakes (Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda).[3] Given the overall scarcity of information on the matter, the report will accomplish this analysis through the following approach. First, a thorough explanation will be provided for China’s overall objectives in the region, outlining the scope of the Chinese presence. Second, the key security threats and challenges faced by Chinese companies in the region will be outlined, providing possible tools that could be used to deal with these issues. Third, examples will be presented that illustrate the operations of some specific Chinese PSCs in Anglophone Africa to provide more context to the nature of activities and tasks performed by these entities in the region.

In addition to a vast collection of local (African) and Chinese-language sources, the report benefits from information obtained from an interview with Paul Nantulya, who is one of a few world class experts on Chinese PSCs in Africa.[4]

The Scope of the Chinese Presence in Sub-Saharan Africa: Past and Present

China in Africa: A Brief Historical Overview

Much debate is had among historians regarding the timeline for when the first contact between China and the African continent emerged. According to Li Anshan, professor emeritus at Peking University and president of the Chinese Association of African History, this may have occurred between 138 and 126 BCE; others refer to the period between 1070 and 954 BCE.[5]

Subsequently, in the Middle Ages and beyond, China maintained strong commercial interests in Africa. The Chinese presence on the continent dramatically subsided during the Qing Dynasty (大清; 1644–1911) when China`s power weakened dramatically. The revival of Chinese interest in Africa coincided with the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 marked by the victory of the Communist forces. The Communist political leadership saw African nations as potential neophytes of the Maoist ideology and highly valued strengthening economic ties due to Africa’s immense wealth in natural resources critical for the rapidly industrializing People’s Republic of China (PRC).[6]

The PRC’s formal manifestation of its interest (and ambitions) in Africa emerged in 1955, when in the city of Bandung (Indonesia) during a large conference with a number of Asian and African countries, then–Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai (周恩来) met with representatives from Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, Sudan, Liberia and Ghana.[7] Later, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, during the most violent stage of the decolonization process, the PRC emerged as an active—though less visible than the Soviet Union and the US—stakeholder in African affairs. Interestingly, at that time, some African leaders—in Angola, Zimbabwe and Tanzania—openly expressed admiration of the Chinese model of socialism. Meanwhile, Chinese instructors were training guerrilla fighters across the continent.[8]

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and Russia’s near full withdrawal from the continent, China rapidly moved in to fill the emerging void. Already in 1992, Africa was visited by then–Chinese President Yang Shangkun (杨尚昆), which resulted in the formulation of six fundamental principles for determining China’s presence in and —including Beijing’s support for the African countries’ sovereignty; freedom of trade; non-interference in the internal affairs of the African states; promotion of economic integration; supporting the African countries in their integration in global economic affairs; and equal partnership– determining China’s presence in and cooperation with Africa. In a broader sense, those revolved around two fundamental principles: non-interference in domestic affairs and the prioritization of economic development and forging business ties.[9] In many ways, this platform for cooperation with the African states three decades continued to dominate Beijing’s actions on the continent for many years, up until now. China’s growing presence on the continent has been dramatically boosted through involving African countries in the BRI.

Anglophone Africa and the BRI

Currently, as many as 46 (out of 54) African countries have confirmed their participation in the BRI.[10] Willingness to participate in this mega-project is reflected in African nations having the “most positive view of the BRI than anywhere else outside China.”[11] Beijing’s interest in including the African countries—and more so when it comes to the Anglophone part of the continent—in the BRI is understandable. In addition to vast deposits of critical natural resources, rare earth minerals and bio-marine resources, countries such as Nigeria and Ethiopia present huge potential as rapidly developing markets with young labor forces.

China’s growing economic and political expansion in Africa—largely, yet not exclusively, done under the umbrella of the BRI—has alerted many Western experts and policymakers who view Chinese actions as an example of neo-colonialism. For instance, it has been argued that no one should be deceived by the BRI as some sort of Marshall Plan; it is “cheap bait” for African countries.[12] Other experts have contended that, in addition to natural resources, China is drawn by the cheapness of labor in Africa—a strategic prerequisite for outsourcing production from China to the continent—with wages being up to six-times lower than in coastal China.[13] Importantly, even the World Bank named such aspects as “debt sustainability, stranded infrastructure and damage to local communities and the environment”[14] as the key risk factors posed by further development of the BRI.

Financing: Foreign Direct Investment, Trade and Business Ties

In effect, Chinese investments in Africa started to increase well before the official launch of the BRI, beginning with the launch of the “Go Out” policy (走出去战略) in 1999.[15] Between 2000 and 2020, Chinese investments in Africa grew by a breathtaking 25 percent per year,[16] making China the largest investor on the continent (by jobs and capital) and third by total number of projects.[17] As of 2020, Beijing’s key economic and trade partners on the continent were primarily Anglophone countries that included—with the exception of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—Kenya, South Africa, Ethiopia and Nigeria.[18]

That said, over time, China’s entry and operational business model in Africa has also evolved: Instead of “going to Africa,” the model has developed along the “settling in/setting down roots in Africa” paradigm.[19] This is construed by business and economics experts as a sign that “African countries are not seen by Chinese investors as low-cost destinations to produce for third markets, but rather as viable markets in their own right.”[20] Debatable as this may be given current circumstances, it is still apparent that, in addition to investment in labor-intensive and resource-related industries, today, the Chinese presence in Africa is gaining more sophistication—undoubtedly, this varies from country to country—which is likely to entail a greater need for China’s physical presence (managers, specialists and tangible assets) on the continent.

Infrastructure as the Key Factor for Involvement

The 2021 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (中非合作论坛; FOCAC) meeting—originally launched in 2000—confirmed that China`s involvement in Africa and cooperation with regional actors will be primarily premised on participation in and financing of large infrastructure projects (mainly done via loans). This was additionally highlighted by Chinese President Xi Jinping, who identified nine specific areas that will drive Beijing’s cooperation with African countries—the most notable aspects being the promotion of medical and health cooperation, trade and business cooperation, digital innovation, cultural exchange, as well as continued military and security cooperation.[21]

Speaking about the infrastructure aspect, between 2007 and 2020, China’s two main overseas development banks invested $23 billion in infrastructure projects on the African continent, effectively exceeding the other top-eight lenders combined, including the World Bank, African Development Bank, as well as US and European development banks.[22] Examples of some notable infrastructure projects sponsored or financed by China in Africa can be found in the table below.

Major Chinese-Supported Infrastructure Projects in Africa

Project Borrowing Country Estimated Cost

Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway Ethiopia $1.3 billion

Karuma Hydroelectric Power Plant Uganda $1.4 billion

Entebbe-Kampala Expressway Uganda $350 million

Memve’ele Hydroelectric Power Plant Cameroon $500 million

Abuja Light Rail Nigeria $500 million

Mambilla Hydroelectric Power Plant Nigeria $5.8 billion

Nairobi-Naivasha Railway Kenya $1.5 billion

Walvis Bay Container Terminal Namibia $250 million

Lagos Rail Mass Transit Blue Line Nigeria $1.2 billion

Lekki Deep Sea Port Nigeria

$1.5 billion

Source: Author.

Interestingly, in addition to traditional infrastructure projects—rail and expressways, seaports, water supply and sanitation, as well as conventional energy—“renewable energy projects have attracted more Chinese investments in Africa than other sectors, including fossil fuels.”[23]

Diplomacy, Soft Power and Other Forms of Influence

In terms of soft power in Africa, China is primarily relying on the following tools. First, diplomacy and sub-national international organizations—such as the FOCAC—provide the Chinese with a necessary level of credibility. Today, it has been argued that the FOCAC can be viewed as a mini-version of multilateral cooperation that aids the implementation of BRI projects.[24] In the realm of diplomatic activities—elevated to a new qualitative level starting in the early 1990s—China has dramatically intensified its actions following the launch of the BRI. Between January and March 2022, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) held talks with Algeria, Egypt, Gambia, Niger, Somalia, Tanzania, Zambia, Eritrea, Kenya and Comoros.[25] Additionally, in March, Xi held a phone conversation with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who fully supported deepening economic and political ties with China and reiterated his support for Beijing’s policies on Taiwan, Tibet and other major issues, including, for instance, the Russia’s war against Ukraine. Namely, it was stated that “both sides agree that China and South Africa share a very close position on the Ukrainian issue and that sovereign countries are entitled to independently decide on their own positions.”[26]

Second, Beijing employs the rhetorical juxtaposition of Chinese and Western practices in Africa. The key theme used by the Chinese side is the “anti-colonial” narrative—incidentally, actively employed by the Russians as well[27]—which Beijing started to develop around 2015, when Wang Yi (during his trip to Kenya) stated that “[China] absolutely will not take the old path of Western colonists, and we absolutely will not sacrifice Africa’s ecological environment and long-term interests.”[28]

Third, China highlights the gratuitous aid and humanitarian assistance it offers to African states. Leaving the COVID-19 situation aside, in 2017, over half of Chinese foreign aid was distributed in Africa.[29] At the same time, between 2000 and 2019, loans from China to Africa were estimated to have reached $153 billion.[30]

As a result of these and many other factors, the perception of China in Africa has been increasingly positive. In effect, China and the US remain two of the most positively viewed powers by African populations.[31] Perhaps, even more importantly, China enjoys growing popularity among young Africans (ages 18–35), among whom 60 percent of respondents said that Chinese influence is “somewhat” or “very positive.”[32]

Even so, with its growing involvement in Africa, China is facing a number of challenges and security concerns that warrant non-standard solutions.

Security Threats and Challenges for China in Africa

Challenge One: Hate Crimes and Sinophobia

Despite the overall positive perception of the BRI and China itself on the continent, the growing Chinese presence in Africa does not always find support within African societies, which sometimes takes on the form of overt Sinophobia.[33] Arguably, three major factors make African citizens particularly unhappy with the PRC’s increasing presence on the continent.

First, China frequently fails to comply with basic principles of ecological sustainability—including illegal fisheries,[34] contamination of coastal areas, illegal and damaging handling of timber production,[35] as well as heavy involvement in the exploration of local rare earth minerals[36]—which has had a severe impact on local ecosystems.

Second, the Chinese side seemingly disregards key principles of social sustainability, which typically translates into the mistreatment of local populations.[37] Frequent instances of anti-African racism have been noted within Chinese society[38]; in this regard, the outbreak of COVID-19 has witnessed a further development of this trend.[39] Additionally, some Chinese private companies operating in Africa have been accused of maintaining openly discriminatory practices toward local population.[40] Other experts have noted racist comments made by Chinese officials with regard to the local population that resulted in the deportation of a Chinese national.[41] As a result of mistreatment of local workers, Zambia witnessed the so-called Chambishi riots (2006) that broke out due to the Chinese side negating safety rules at a copper mine site, which resulted in an explosion that killed 46 Zambian workers.[42] In response to the riots, the Chinese shot six Zambians. In 2007, then–Chinese President Hu Jintao, on an official state visit to Zambia, was forced to cancel a visit to the mine to avoid mass protests.[43] In 2011, Human Rights Watch released a report titled “China in Zambia: Trouble Down in the Mines,” pointing to multiple instances of the mistreatment of Zambian workers in Chinese-owned copper mines.[44] In effect, many experts believe that China’s racism may have profound negative consequences for the country`s overall successful course in Africa.[45]

Third, the aforementioned factors frequently result in hate crimes that include violent protests and counteractions against (previously mentioned) instances of mistreatment of indigenous population by Chinese nationals and companies. For instance, reports have attributed the stoppage of some major infrastructure projects conducted by Chinese companies to waves of anti-Chinese public protests and instances of violence.[46] Among others, one key source of violent anti-Chinese actions has been the lack of engagement with locals in lucrative infrastructure projects carried out by the Chinese in Africa[47] as well as the existence of so-called “white elephant projects.” This term refers to large infrastructure initiatives—such as the two new stadiums that were funded and built by China in the Zambian capital of Lusaka and in Ndola or the Lusaka-Chirundu road constructed by China Henan International Cooperation Group (中国河南国际合作集团有限公司)—that, according to local activists and the political opposition, breed corruption and promulgate indebtedness of local economies to China.

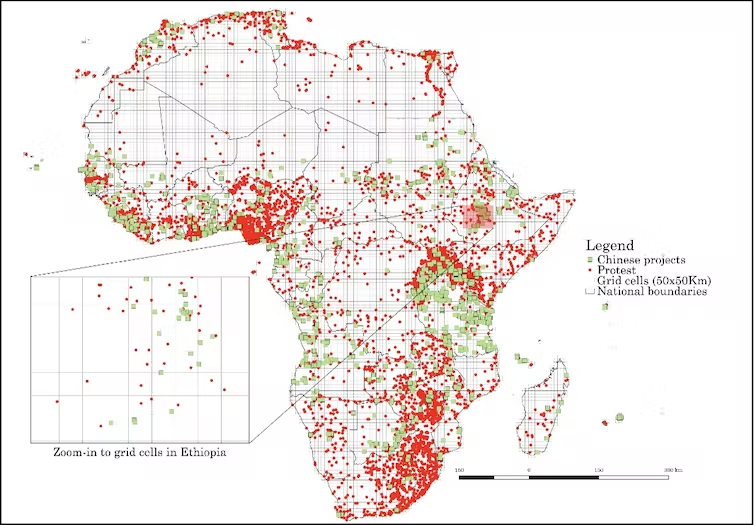

Map of Chinese Protests in Africa, 2000–2014

Challenge Two: Terrorism and Radicalization

According to one recent report, in 2021, no less than 3,500 victims of terrorist acts—nearly half of all those recorded worldwide—were registered in Sub-Saharan Africa.[48] For China, 84 percent of its BRI investments are in medium- to high-risk countries,[49] and the number of Chinese workers in Africa by the end of 2020 was 104,074.[50] Thus, the specter of terrorism poses a significant challenge to Chinese operations. In addition to well-known existing hotspots—such as Nigeria and the Sahel, with historically high levels of extremism and violence[51]—new areas of Sub-Saharan Africa (with a significant Chinese presence) are rapidly being affected. Countries including Ethiopia,[52] Togo (which puts additional pressure on Ghana),[53] Tanzania[54] and even South Africa[55] are demonstrating signs of growing underground radical movements.

Challenge Three: Kidnappings for Ransom and Organized Crime

Kidnappings for ransom and organized crime—for now, these challenge constitute a greater threat to Chinese nationals in Africa than terrorism alone—were named in the UN Security Council report as key developmental challenges for many African countries.[56] Overall, it seems the most frequent cases of kidnappings have been reported in Nigeria, where over 1,000 people were kidnapped in 2021 alone.[57] As noted in one report, “Kidnapping for ransom, which used to be common in Nigeria’s oil-producing south, has lately spread to other parts of the country. The victims are usually released after a ransom is paid, though police rarely confirm if money changed hands.”[58] Frequent kidnappings of Chinese nationals in Nigeria—which remains the main destination of Chinese foreign direct investment in Africa (over $40 billion in 2020) and for Chinese workers[59]—have already caused open disdain from Chinese officials. Specifically, in response to the kidnapping of two Chinese nationals in the country, the Chinese Consulate-General in Lagos launched an emergency plan, urging the Nigerian police to make every possible effort to rescue the hostages. The plan was presented by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian (赵立坚)—one of the most prominent representatives of Beijing’s so-called “wolf warrior diplomacy” (战狼外交)—at a press conference in April 2021.[60]

According to Oluwole Ojewale, an analyst at the South Africa–based Institute for Security Studies, extremist groups and criminal gangs are seeking profitable ransoms, being under the impression that the Chinese companies operating in Africa have substantial financial means and could easily pay ransoms for their employees. Ojewale also argues that, from their side, large Chinese corporations “will now have money set aside for such security risks and will either pay ransoms or use private security operatives to try to protect their staff.” He added that “profits will likely trump security concerns. … Chinese businesses will pull out … irrespective of how volatile the environment is.”[61] This means that, in their operations on the African continent, Chinese companies would have to increase their reliance on PSCs.

Chinese PSCs in Africa

China’s Security Presence in Africa

The Chinese security presence on the African continent—by no means new[62]—is complex and multifaceted. In addition to emerging (para)military facilities and activities of PSCs, China relies on several other forms of security engagement as well.

(1) Peacekeeping Missions—According to official reports, in 2019, China became the second-largest contributor to both peacekeeping assessments and UN membership fees[63]—a fact that the Chinese political leadership takes pride in and emphasizes in propagandist commercials and documentaries, such as the “Blue Defensive Line” (蓝色防线).[64] In 2020, Chinese peacekeepers (2,000 members) took part in missions in the DRC, Mali, Sudan, South Sudan and the Central African Republic.[65]

(2) Integration in African Security via Collaboration With Major Regional Security Organizations—For example, China has been actively involved in the establishment of the African Standby Force and a rapid-response force. Additionally, during the 70th anniversary celebrations of the PRC’s founding at the UN headquarters in New York, State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) declared that “more than 2,000 Chinese peacekeepers were defending peace in Africa. … The Chinese Navy has guarded more than 6,700 ships during escort missions in the Gulf of Aden and waters off the coast of Somalia.”[66]

(3) Arms and Weaponry Sales—This tool has remained a key Soviet/Russian strategy in security projection on the continent and now has become an important element of China’s strategy in Africa. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, between 2015 and 2019, China emerged as the second-largest arms supplier, after Russia, to Sub-Saharan Africa (19 percent of the region’s imports), effectively overcoming France (7.6 percent). In this, two key aspects should be highlighted. First, China is now switching to selling more advanced and sophisticated weaponry, such as the CH-3 unmanned combat aerial vehicles, known as the “Rainbow” series,[67] and main battle tanks,[68] which is directly related to the intensification of anti-rebel operations by some African governments. Second, to effectively employ these pieces, African militaries will require Chinese instructors, which will increase the presence of Chinese security personnel on the continent.

(4) Military Education—This approach is used by the Chinese in Central Asia, too,[69] as a means to cultivate current and future African security leaders and create connections and networks of linkages that will be profitable for Chinese companies in the future.[70] One notable example of this is the China-funded training center for Tanzania’s military at Mapinga.

General Features

While some sources attribute the emergence of the first Chinese PSCs in Africa to 2010 as part of China`s move to protect its ships from Somali pirates,[71] other sources mention 2013 and the official launch of the BRI.[72]

Speaking about Chinese PSCs in Africa, several crucial aspects pertaining to general image and the landscape of the private security contracting industry in Africa should be mentioned. According to César Pintado, this market is characterized by the following particularities[73]:An ingrained image of the mercenary of the post-colonial period. As during the decolonization period a great number of brutal armed conflicts occurred in Africa that left a visible scar on their historical memories of some African countries;

Numerous armed groups offering their services, including Chinese companies even before the BRI;

The return of highly competent PMCs that support local governments or serve non-African interests;

Shortcomings of local security forces;

A move from oligopolistic (with a limited number of security providers based in Washington, London or Cape Town) to a true free market with a multitude of companies at different levels;

The need to rely on a network of informal ties and individuals—journalists turned into “fixers” or investigators—dedicated to intelligence gathering.

From his side, Alessandro Arduino emphasizes the following main aspects. First, the African continent still carries the stigma of mercenaries’ behavior during post-colonial conflicts. Second, well before the launch of the BRI and Beijing’s endorsement of PSCs going abroad, several Chinese companies in Africa, operating in a range of sectors from natural resource extraction to small businesses, organized private armed “militias” to protect their interests against criminal or political violence. Third, while the footprint of Chinese PSCs is still limited, Africa is witnessing a return of the global “soldier of fortune” in support of local government and international interests.

Arduino also perceptively acknowledges another key trend that now defines (and is likely to continue to do so) the changing security milieu on the African continent: If in the past there was a clear historical division of roles between US support for Africa on military and counterterrorism while China’s role boiled down to economic and trade considerations, now that division is progressively blurring, and China is becoming increasingly integrated in security-related matters on the continent.[74] To some extent, this follows the patterns of Chinese involvement in Central Asia, where China is becoming progressively involved in security-related issues that used to be fully delegated to Russia.

Selected Examples of Chinese PSCs

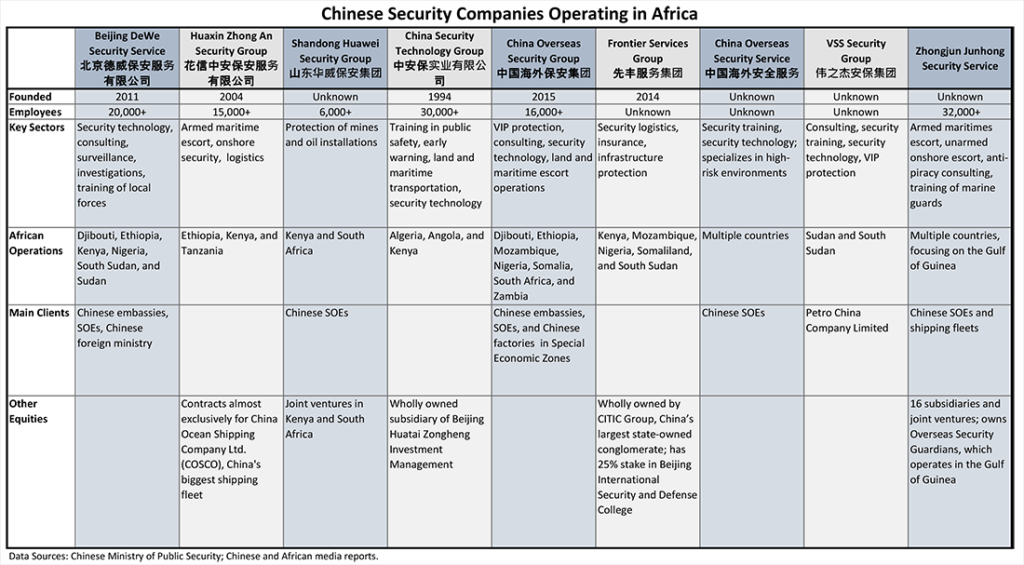

The table below contains a list of known/identified Chinese security providers operating in Africa. Given the general scarcity of information and the actual focus of this report (Anglophone Africa), analysis will concentrate only on some of the security providers operating on the continent.

The first PSC, Hua Xin Zhong An (HXZA; 华信中安集团), is a privately held firm founded in 2004 by veterans of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The number of employees within the organization varies (based on several sources), with between 15,000 and 28,000 employees operating in more than 21 countries.[75] Yet, the company itself claims that only up to 400 of its security personnel are deployed in Africa, with the rest being primarily stationed in mainland China.[76] Starting from 2011, HXZA has been deploying (armed) maritime personnel.[77] Additionally, the company is fully licenced to provide land-based services—to assist the PLA Navy’s anti-piracy operations.

Aside from its operational area, which includes such high-risk areas as the Gulf of Aden and the Gulf of Guinea (see map), HXZA is one of only a few Chinese PSCs that is allowed to carry weaponry abroad,[78] which is rather atypical given the stance of the Chinese political leadership on this sensitive issue.[79] Another key feature about the company is that it became the first PSC from East Asia to obtain certification under ISO 28007 of the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA) certification.[80] As noted by Arduino, “The role of HXZA is quite peculiar as it offers a peek into the future of Chinese PSCs. HXZA is one of the first Chinese security companies that has been able to obtain a permit from the Chinese government to legally carry weapons abroad and to employ foreign consultants. … It has proven its ability to work to internationally recognized standards and to improve efficiency while simultaneously looking at the well-being of local stakeholders.”[81] Below are areas in Sub Saharan Africa, where HXZA has been spotted.

HXZA Areas of Operation

Source: Investigative Journalism Reportika.

Second, Frontier Services Group (FSG; 先丰服务集团) is a Hong Kong–listed PSC that has a special emphasis on operations in Africa (with offices in Nairobi and Johannesburg). Its client industries include oil and gas, mining, finance, international organizations, energy and infrastructure.[82] While the company was founded and led until April 2021 by Erik Prince (former Navy SEAL and founder of US-based PMSC Blackwater), recent developments—when the company was overtaken by Chinese state-owned enterprise CITIC Group (formerly known as China International Trust Investment; 中国中信集团有限公司)—clearly demonstrated Beijing’s strategic interest in FSG, which was unlikely to tolerate private initiatives in providing security on Chinese territory.[83]

Interestingly, the current chairman of the Board is Chang Zhenming (常振明), who used to serve as chairman of CITIC Group. Judging by previously voiced facts (when the company preserved a veneer of “privacy”), the company was primarily dealing with “providing personal security” without the use of weaponry.[84] Rumors also circulated about the company’s involvement in “anti-terrorist security trainings”—which, in the Chinese context, has a broad and frequently negative (given the Uyghur issue) meaning—was viewed poorly in the West.[85] Other sources, however, point to logistics, civil engineering and assistance services as FSG’s main activities.[86]

Additionally, despite the company`s claim that its main interests in Africa are concerned with the “Southern Africa Region,”[87] the map below shows that FSG has interests spreading beyond the boundaries outlined by the company itself.

FSG Areas of Operation

Source: Investigative Journalism Reportika.

Third, Overseas Security Guardians (OSG) was established by ZhongJun JunHong Group (中军军弘保安服务有限公司) and was the first to receive Chinese government authorization to provide armed maritime escorts to Chinese fleets.[88] It is also a member of the ICoCA. Being a conglomerate of five firms, the company has strong interests in the African portion of the BRI.[89]

OSG Areas of Operation

Source: Investigative Journalism Reportika.

According to OSG`s website, its main operational domains include the following.[90]The company provides land security services in more than 30 branches, offices and bases around the world. In these activities, the group closely cooperates with China Railway No. 5 Engineering Group (中国中铁五局集团有限公司), which is active in Benin, Ghana, Uganda, Liberia and Zimbabwe,[91] and Huawei Technologies, which has been called a “top employer” in Africa for 2023.[92]

OSG carries out maritime missions in Mombasa (Kenya), Dar es Salam (Tanzania), Durban (South Africa) and Toamasina (Madagascar). (See map below.)

OSG Maritime Operations

Source: Zhongjun JunHong Security Service.

OSG also conducts security trainings, including anti-terrorism drills both domestically, such as the Langfang Armed Police Command College (Hebei), and overseas (Laos and Kyrgyzstan).

The company engages in security consulting that follows along seven main lines of security risks: “political orientation, social unrest, public security (criminal) cases, terrorist attacks, natural disasters, accidents and public security.”

From a staffing point of view, the PSC claims that its core consists of both domestic army retirees as well as “experts from the United Kingdom, America, South Africa, Germany and Malaysia. … Soldiers retired from the army, navy, air force and armed police are sources of security officers.”

Fourth, and the final selected example for this report, is Beijing DeWe Security Service Group/Dulwich International Security Group (DeWe), whose activities have been thoroughly studied by Paul Nantulya.[93] This particular PSC is said to be “one of the most well-known overseas Chinese [PSC] firms.” The company was established in 2011 by former PLA and People’s Armed Police officers.[94] Its website mentions the following corporate clients (all of which have been involved in activities in Africa): the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Commerce and Ministry of Education. Other partners include Hanban (汉办), also known as the Confucius Institute Headquarters; China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation; China Communications Construction Company; China State Construction Engineering Corporation (formerly known as the China State Construction Group); and China Development Bank.[95] The PSC has been involved in operations in Africa since 2013—including, among others, Ethiopia and Nigeria—collaborating with African police, military and domestic security companies.

Specifically, in Anglophone Africa, DeWe has been involved in the following projects:In Ethiopia, the company has been involved in the protection of a $4 billion cooperative natural gas project between Ethiopia, Djibouti and China,[96] also known as the “largest project” that Chinese overseas security contractors have been hired to secure.

In Kenya, the company has been training local guards along a $4 billion Chinese-built railway, the “largest infrastructure project in 50 years [in Kenya].”[97]

In South Sudan, DeWe has been providing security assistance for the China National Petroleum Corporation.[98] In 2016, the PSC found itself in a crisis in Juba that involved clashed between local factions. Incidentally, DeWe personnel were involved in another crisis situation in Uganda, which, as argued by Nantulya, was only resolved due to Beijing’s involvement—not DeWe, whose personnel were unarmed.

In general, despite a cautious approach, Chinese PSCs operating in Africa have been involved in several notable incidents in Zimbabwe,[99] Kenya,[100] Zambia,[101] Kenya and Uganda.[102] Overall, these (and similar) incidents have had a negative impact—though the damage is not irreparable due to the strength of economic and business ties—on China`s image in Africa.

Controversies and Complications

According to Nantulya, the increased involvement of Chinese PSCs in Africa is accompanied by three main controversies. First, African governments and citizens tend to view Chinese security contractors as part of the Chinese government, not independent entities. In truth, Chinese contractors are rather explicit about their role in advancing Beijing’s security goals. These operatives are also generally viewed as being part of China’s arms marketing push, given that they also advertise and sell security equipment to local partners.

Second, as noted earlier, some, including security-related, incidents—such as instances of illegal pouching, racism, and the violent put down of local protestors—may taint the image of both PSCs and the Chinese state, since the two are inseparable in the view of many Africans.

Third, even though Chinese PSCs are neither heavily armed (unlike Western PMSCs) nor have they been involved in reported war crimes or military conflicts (unlike Russian quasi-PMCs/mercenaries), Africans still view the presence of Chinese security providers on their territory in a negative light. As noted by Nantulya, African nations have yet to heal from the wounds left by mercenary activities on the continent during the Cold War. Moreover, multiple human rights violations by both African (Executive Outcomes) and foreign (e.g., Sandline International and Wagner Group) PMCs—in addition to the horrors of the civil wars in Algeria, Angola, Liberia, Libya and Sierra Leone, where PMCs and mercenary formations took an active role—further taint the image of private security providers, rendering them unwarranted on African soil. On top of that, investigative reports have claimed that Chinese large corporations—such as China National Petroleum Corporation—are involved in regional conflict by “providing material support to a pro-government militia” that resulted in atrocities and violence against civilians.[103]

Conclusion

While ample proof underlines that Chinese PSCs are present in the Anglophone part of Africa, many specific (and crucial) details related to their actual tasks and functions, specific projects and responsibilities, as well as the level of collaboration with local authorities, remain unknown due to the high level of secrecy and opaqueness in the local informational milieus. Frequently, the facts undergirding the presence of Chinese security providers in a given country becomes known as a result of a security-related incident and/or controversy. At the same time, Chinese PSCs—let alone the government officials and large business that are inseparable from the state—rarely share information about their involvement (aside, perhaps, from general information) and their presence on the continent and the specific parts thereof. What is clear, however, is that China`s use of PSCs on the African continent, and in Anglophone countries in particular, will continue along three main lines.

First, this, as noted by Nantaluya, will be an incremental process, and Beijing is unlikely to accelerate the trend. In many ways, this is stipulated by the fact that China itself is still in search of an ideal format for organizing its PSC industry, which, as noted in a previous report, has yet to reach the level of its foreign counterparts.[104] As for their current form and capabilities, Chinese PSCs are unlikely to effectively carry out tasks associated with the protection of Chinese nationals and assets in Africa, especially when challenges go beyond petty crimes and kidnapping incidents. For these entities to be able to aptly respond to more serious challenges, Chinese PSCs should transform into genuine PMSCs of the Western type.

Second, African states—while generally holding a positive opinion about China and welcoming its investments, large business initiatives and infrastructure projects—do not feel comfortable with the idea of (armed) Chinese nationals being present on their soil; some of the aforementioned security incidents only strengthen this feeling. Thus, China—which is now starting to play a key role in the realm of business and trade on the continent—would not want to spoil its perception in Africa by increasing its security presence there. Yet, as noted, multiple security challenges and the need to protect its nationals and tangible assets will make Beijing look for alternative solutions.

Third, the Chinese side could use testing grounds—that is, smaller and economically weaker African countries—to elaborate on and develop various forms of cooperation with African nations in the realm of building (non)conventional security ties. For instance, in an interview with this author, Nantaluya argued that closer attention should be paid to Lesotho, where Chinese influence and presence is overwhelming. In the country, the Chinese side has not only established a steady cultural (via the Confucius Institute) and economic presence but is also actively building ties with the Royal Mounted Police and the military. Perhaps, akin to Djibouti (as a Francophone country, whose case will be further developed in the next report), Lesotho and other heavily indebted and economically weaker African countries could become a testing ground for China to develop security cooperation along the lines of private security contracting.

No comments:

Post a Comment