Grigory Ioffe

As a relatively small country squeezed between two increasingly antagonistic centers of power, Russia and the European Union, Belarus has always stood out for its dependency on multifaceted external factors. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated this dependency and added new aspects to it. Thus, attitudes regarding ordinary Belarusians have noticeably worsened in Ukraine and three neighboring countries—Latvia, Lithuania and Poland—that are also members of the EU. As a result, Belarusian émigrés often feel that landing a job, renting an apartment, as well as receiving a residency permit have become more difficult. “Why Do They Dislike Us So Much? How Can Belarusians Challenge Unfriendly Attitude Towards Themselves?” reads the title of a recent article from Yury Drakakhrust (Svaboda, April 19). According to him, the gist of the matter is Belarus’s complicity in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Additionally, not too many people abroad are willing to separate Belarusians themselves from the current political regime. In Drakakhrust’s opinion, unfriendly feelings toward Belarusians are not merely the outcome of respective governments’ resentment toward Minsk, at least not entirely; more likely, they are grassroots reactions per se.

Two recent developments are intimately related to the topic in question, including one that, by some accounts, reflects a positive outcome of the organized Belarusian opposition-in-exile’s effort to alter attitudes. Thus, the Lithuanian Parliament recently overcame the Lithuanian president’s veto on a bill that would differentiate between the legal situations of Belarusian and Russian citizens in Lithuania (Current Time TV, April 20). President Gitanas Nausėda’s original idea was to refrain from such a differentiation whereby applications for permanent residency and citizenship as well as buying property would no longer be approved when it comes to both Russian and Belarusian citizens. However, based in part on lobbying by Svetlana Tikhanovskaya’s “cabinet,” the parliament altered the president’s bill, making limitations imposed on Belarusians softer than on Russians (Zerkalo, March 29). When Nausėda vetoed that alteration, 99 members of parliament voted to overcome his veto, with seven members voting to sustain it and two abstaining (Gazetaby, April 20).

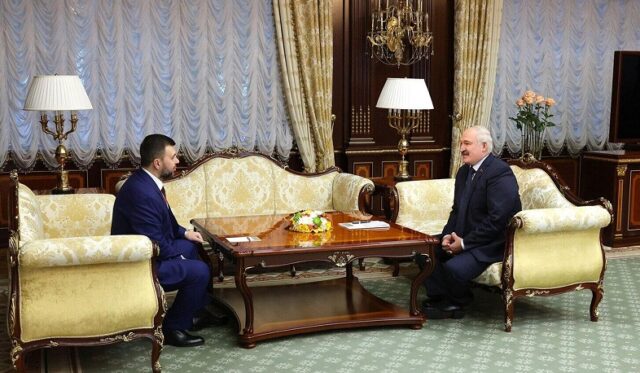

The second development is highly likely to have a different effect on attitudes, at least in Ukraine, Belarus’s southern neighbor. Specifically, on April 18, President Alyaksandr Lukashenka received Denis Pushilin, head of the so-called Donetsk “people’s republic” illegally annexed by Russia. After the meeting, Ukraine recalled its ambassador to Minsk for consultations (RBC, April 19). Yet, there is a peculiar contrast between Pushilin’s most recent visit and his previous arrival in July 2022. At that time, even Belta, Belarus’s official press agency, did not mention it, and no national-level official accompanied Pushilin. Instead, he was accompanied by the Russian ambassador to Belarus, Boris Gryzlov, and chair of the United Russia party, Andrei Turchak (see EDM, August 2).

In contrast, this time, Pushilin was received by Lukashenka himself, with whom he discussed economic cooperation (Sputnik.by, April 18). While opposition-minded commentators are unanimous in that, with the passage of time, Minsk’s degree of autonomy from Moscow is diminishing, which explains the difference in question, they are not unanimous as to why Ukraine reacted the way it did now but refrained from a similar protesting gesture in the recent past. Thus, Artyom Shraibman of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace confessed he is mystified by that gesture’s timing simply because Pushilin’s reception in Minsk is “a much less escalatory move compared with those that took place earlier” (Euroradio, April 19). Indeed, even when Lukashenka called his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelenskyy a “crumb bum” (YouTube, March 7), Ukraine’s ambassador to Belarus was not recalled. And many commentators agree that recalling the ambassador will not lead to a rupture in diplomatic relations.

It could be that Ukraine counts on some kind of intermediary role that Minsk may play and thus differentiates between it and Moscow. If that is the case, appeals for a truce from Lukashenka and Foreign Minister Sergei Aleinik dovetail with such expectations. In the opinion of one of Lukashenka’s most ardent critics, Valer Karbalevich, the Belarusian president is pursuing two primary courses of action. He is stoking “war fever” by agreeing to accept Russian nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory and by soliciting security guarantees from Moscow. At the same time, he continues to seek contacts in the West, and the recent visit of Aleinik to Budapest bears testimony to that. In Karbalevich’s view, these two courses “contradict each other, they run parallel, and they do not intersect in any way” (Sn-plus.com, April 16). Perhaps the Belarusian critic’s peculiar imagery (lines that run parallel but somehow contradict each other) is associated with his own dual ability to explain and castigate simultaneously, which he demonstrated in his 2010 biography of Lukashenka. Likewise, in this case, Karbalevich explains that Lukashenka’s militarism derives from the fact that he feels cornered, while his appeals for peace derive from feeling uncomfortable in that “corner.” Moreover, Lukashenka’s appeals match what Belarusians en masse want (Gazetaby, April 14).

Incidentally, as some voices emanating from Minsk predict, “In the coming months, we are likely to witness a rather rapid transition from the acute phase of the conflict [in Ukraine] to the negotiation process” (NarodnayaVolya, April 14). Such is the opinion of Denis Melyantsov from Minsk Dialogue, which has not yet been shared by other commentators. According to Melyantsov, the political situations in Washington, Moscow and Kyiv relentlessly evolve in the direction of a dialogue. If that is the case, Lukashenka’s intuition may hit the mark, as it did many times in the past.

Going along with this, Belarus’s economic slump appears to be not as grave as originally predicted based on Western sanctions, and growth has resumed (Svaboda, April 20). Moreover, anecdotal evidence from a Belarusian trucker regularly driving between Poland and his home country suggests that, due to ingenuity and informal cooperation of custom services on both sides, sanctioned goods cross that border at full throttle (Facebook.com/IlyaDobratvor, April 19).

In any case, as political perceptions regularly deform our understanding of otherwise verifiable facts, all bets are off. And this pertains to external influences on Belarus, chances for peace and Minsk’s active role, whether it is visible or not at the moment.

No comments:

Post a Comment