Afew days after Thanksgiving 2022, Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense tweeted a head-on photograph of an M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) launcher, its headlights illuminating a rainy night. Painted wide across the front of the truck and its open doors was a menacing, reptilian smile. With its pair of squat windshield portholes standing in for eyes, the weapon looked distinctly like a creature from Tim Burton’s classic film The Nightmare Before Christmas.

“In anticipation of Christmas, a smiling Himars [sic] collects occupiers under Christmas trees,” the caption read.

The barb, full of the insolent bravado that has made Ukraine’s social media accounts globally popular, played up the near-celebrity status that the HIMARS mobile rocket launcher has achieved among Ukraine’s supporters. Sweatshirts announcing “It’s HIMARS O’Clock” and stickers emblazoned with an image of the coffin-shaped launcher loaded and aimed skyward all offer a winking way to taunt Russian invaders. In October, the launcher was crowned “The Coolest Thing Made in Arkansas” by that state’s chamber of commerce, beating out Frito-Lay’s Cheetos, the iChill Mattress, and aviation fuel cells.

While it may seem strange for a mobile weapons system designed to send a barrage of destructive missiles dozens of miles at more than twice the speed of sound to achieve the popularity of a movie character or a meme, the adulation of HIMARS makes sense in light of the destruction it has unleashed on the Russian army. Since the U.S. Defense Department delivered the first four HIMARS trucks to Ukraine at the end of June 2022, reports of their effectiveness have been steady, if not always verifiable. In late July, HIMARS was reportedly responsible for destroying the Antonivskyi Bridge across the Dnipro River near the Russian-occupied port city of Kherson, which would be retaken by Ukrainian forces a few months later. In October, Ukrainian forces distributed aerial footage showing HIMARS rocket launchers stealthily moving through a forest near the occupied region of Luhansk, and then systematically obliterating a Russian tank convoy. As of September, U.S. defense officials said Ukraine has hit more than 400 Russian targets with HIMARS, while Russia has been unable to retaliate effectively. As of November, none of the 20 launchers in Ukrainian hands had been destroyed.

HIMARS’s star turn in Ukraine sparked a rush among U.S. allies to equip themselves with the system and coincided with NATO’s launch of a new HIMARS logistics support structure as a keystone in its defense against Russia. The U.S. military, meanwhile, is busy developing new ways to employ HIMARS and expand its capabilities. Amid the furor hangs a question: Why is HIMARS so good? Has it merely maximized a determined Ukraine’s effectiveness against a Russia unprepared for a modern conflict, or do the weapon’s unique capabilities and design portend an even greater value on future battlefields?

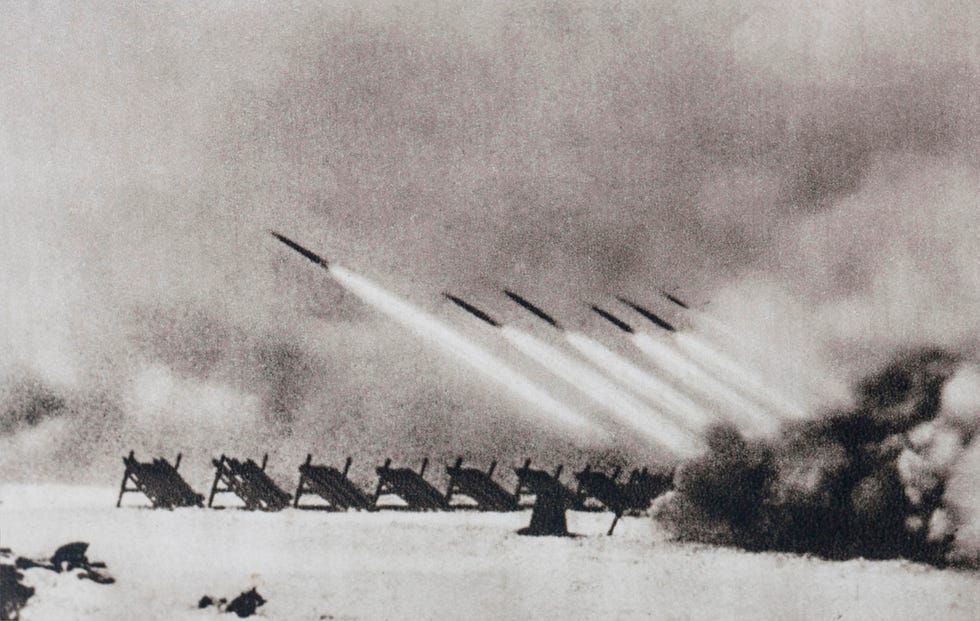

The Soviet Union’s Katyusha was a pioneering multiple-rocket launcher system developed during World War II.Alamy

HIMARS may be newly famous, but it’s not new. The system entered service for the U.S. Army and Marine Corps in 2005 after a decade of development by its manufacturer, Lockheed Martin. It is the most recent advance in a chain of weapons that can fire multiple rockets in quick succession, a game of weaponry one-upmanship that was born out of the Cold War.

The Soviet Union was among the first nations to invest significantly in rocket artillery, fielding the first truck-mounted multiple-rocket launchers during World War II. The Katyusha launchers delivered blanketing destruction rather than precision hits. Early versions, including the 132mm BM-13s, were nicknamed “Stalin’s Organs” because their rows of rocket tubes resembled the piped instrument. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union further developed the Katyusha platform, debuting the BM-21 Grad in 1963. This 122mm launcher, mounted on a 4.5-ton truck chassis, could fire a barrage of 40 rockets in as little as 20 seconds, and reload again in three minutes. Russians had a nickname for this one too: “Hail,” for the way its rockets rained down on an enemy position.

The U.S. military, by contrast, continued to rely on its arsenal of howitzer cannons, which were seen as more reliable and accurate, even if they lacked the range and volume of multiple-rocket launchers. But when the Soviet Union began exporting the BM-21 to other nations, and those nations used the multiple-rocket launchers in their own battles—particularly the 1973 Yom Kippur War between Arab and Israeli forces—the U.S. saw how potent the weapon was, and questioned whether its own forces could defend against it.

In a potential land battle between the U.S. and Russia featuring multiple-rocket launchers, “the Russians were going to come and they were going to last forever,” says John Ferrari, a retired Army major general and nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, recalling the growing concern among American military planners. Howitzers, as steady and accurate as they were, couldn’t sufficiently counter the range and destruction of Russia’s rocket launchers.

The U.S.’s belated answer was the M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System, known as MLRS, which it developed in the mid-1970s. The launcher had space for 12 rockets atop a Bradley Fighting Vehicle—a heavy-duty tracked vehicle resembling a tank. The hulking 26-ton weapon first proved itself in 1991’s Operation Desert Storm, the U.S. campaign to free Kuwait from Iraqi invaders. Recent reporting suggests that the effectiveness of the “steel rain” from the MLRS’s unguided M26 fragmentation rockets was overblown by Army officials to boost future investments in long-range artillery. But Ferrari, who deployed to Kuwait as an executive officer with the Army’s 2nd Cavalry Regiment, remembers being awed by the MLRS during nighttime missions.

The Soviet Union continued development of multiple-rocket launchers throughout the Cold War, while the U.S. invested in shorter-range but more accurate howitzers. In the ’70s, realizing they were undergunned, the U.S. began work on its own MLRS systems.Getty Images

“It alters your life when one of those things fires—it’s so fantastic and big and loud and noisy,” he says. “It’s like being at Cape Canaveral.”

HIMARS came next. Developed in the 1990s, it was built to fire improved MLRS munitions: A six-pack pod of bullet-shaped guided rockets called GMLRS with ranges of more than 43 miles and accuracy within a few feet. While the MLRS mounted on a Bradley Fighting Vehicle chassis can reach top road speeds of 40 miles per hour, HIMARS can hit nearly 60 mph, and accelerate significantly faster than its predecessor. The idea, as always in artillery operations, is to launch a payload and then clear out of the area before an enemy can locate the projectile’s point of origin and respond. The Army calls this tactic “shoot and scoot,” and no ground-based weapon does it better than HIMARS.

Nicknamed “the 70-kilometer sniper rifle,” HIMARS is so accurate that it can hit a single room in a building dozens of miles away. GMLRS rockets are the most common HIMARS payload, and more than 50,000 of them have been made in three variants. The original one, called the Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munitions rocket (DPICM), is now out of service. The GMLRS Unitary has a 200-pound warhead for precision strikes in urban environments. And the GMLRS Alternative Warhead (AW) has a 200-pound explosive warhead that detonates about 30 feet above a target area and rains down 182,000 preformed tungsten fragments. Images posted to Twitter indicate that Ukraine has received both the Unitary and AW rockets. Lockheed Martin also is developing an extended-range version of the GLMRS, which it claims will hit targets more than 90 miles away.

And then there’s the thicker MGM-140 Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) missile, another HIMARS munition, which comes one to a pod and has a 190-mile range. Because the missile could be used by Ukraine to hit targets far inside Russia, the U.S. has so far refused to provide the missiles to the embattled nation.

A predecessor to HIMARS, the M270 MLRS rode atop a tanklike Bradley Fighting Vehicle. The U.S. first deployed it in 1991 during Operation Desert Storm.Alamy

Nikki Rizzi, who was among the first group of female officers the Army permitted to attend field artillery school in 2010, deployed with HIMARS to the operations hub of Kandahar, Afghanistan, as a battery platoon leader in 2011. Rizzi says her artillery battery was tasked with supporting missions from Joint Special Operations Command that required urgent precision and speed: It would be used to target an enemy compound rigged with improvised explosive devices, for example, or to level a terrain feature providing cover to insurgents.

Multiple echelons of command had to sign off on the strike, and airspace had to be cleared to account for the payload’s flight time; rockets could take several minutes to reach their target. Often, Rizzi recalls, the HIMARS unit would coordinate with an A-10 Thunderbolt close-air support aircraft, dropping bombs and firing rockets on the same target.

Inevitably, a HIMARS fire mission would draw a crowd in the tactical operations center where Rizzi worked. The choreography of aviation and ground elements and the precise moment-by-moment communication would culminate in the payload’s release in a concussive plume of smoke through which the streak of rocket fire could be seen. The sound would follow an instant later, an epic crack as warheads capable of reaching velocities 2.5 times the speed of sound hurtled upward. After the GMLRS rounds had disappeared over the horizon, to be tracked from the operations center to their final destination, platoon members liked to search for the shoebox-sized plastic end caps that the spent rockets left behind, saving them for souvenirs or gifts.

“Everyone was always very curious about how it worked. Whenever there was a HIMARS mission, everyone was watching it unfold,” Rizzi says. At the end of her nine-month deployment, her platoon had fired about a dozen missions—more, she says, than any of the platoons that had come before.

Rizzi says the Ukrainian military’s success with the system is amazing, particularly because they operate it without some of HIMARS’s most important guidance systems. The U.S. military’s Advanced Field Artillery Tactical Data System (AFATDS), for example, largely eliminates the need for human calculation: Contained within rugged laptops and communications terminals, the system evaluates target locations, coordinates air and ground elements, and monitors missions in progress. A control panel in the cab of the truck, integrated with HIMARS onboard systems, calculates the elevation and azimuth (a measurement of horizontal direction) of the launcher based on the desired target, and manages the actual arming and firing process. AFATDS leaves little for the crew to do except park the system at the desired location, load the rounds, elevate and rotate the launcher into the prescribed position, and, once safely within the cab, discharge the payload on orders from a fire-direction center.

Without the benefit of AFATDS, a proprietary U.S. military system not included with the launchers sent to Europe, Ukrainian HIMARS operators have had to use drones supported by SpaceX’s Starlink satellite communications network for target identification and reconnaissance, and off-the-shelf radios or cellphones for communication to plan a strike. (SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk, has objected to this use of the technology and taken steps to curb it.) In some cases, the Ukrainians have resorted to the Meta-owned smartphone application WhatsApp to order missions when other comms go down and have created their own smartphone apps for battlefield coordination. (As of December, the Army is seeking to develop an international version of AFATDS that Ukraine can use.)

Once Ukrainian forces identify a target location, aiming HIMARS—even without AFATDS—is quite easy. Troops only have to manually enter grid coordinates, and then fire.

“The simplicity of it in combination with the highly effective weapon system is why they’re being wildly successful with it,” says retired Army Col. John Cochran, a former acting director of the Pentagon’s Close Combat Lethality Task Force.

In July 2022, Ukrainian forces used HIMARS launchers to take out the the Antonivskyi Bridge over the Dnipro river in Kherson, Ukraine. The bridge was part of a crucial supply line that had allowed Russia to occupy the city. Unable to hold the territory, Russia pulled back its forces in November.Getty Images

The alchemy of Ukrainian success with HIMARS, multiple observers have noted, has three key elements: the existential nature of their fight, their aptitude and familiarity with artillery operations, and an uncommon understanding of how their invader operates.

“The Ukrainians, their senior leaders, all grew up in the Soviet-style system,” says Scott Boston, a senior defense analyst with the RAND Corporation and a former artillery officer. “I think that they inherited ... that Soviet prioritization of how to use fires, but also a really deep understanding of how Russians were going to operate. I think that if you put Ukrainian officers in a position where they can see a Russian formation, they’re going to know where to look for a headquarters, where to look for ammo dumps, where the artillery might be hiding in a way that would not necessarily be as intuitive to people who didn’t grow up in that system.”

As the Ukrainian military has become more comfortable employing HIMARS, it’s using the weapon to keep Russian troops disorganized, uncertain, and on the defensive.

“So now the Russians have to expend precious resources to defend. It prevents them from massing on Ukraine’s eastern front, which is what you want,” says Ferrari, the retired Army major general. “You want them to be looking 360 degrees, and to be worried.”

The Russian military has proven itself catastrophically inept at the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, or ISR, that could help them defend against nimble Ukrainian launcher trucks. The pair of spy satellites Russia relies on may be nearing the end of their service lives, and battlefield artifacts indicate that Russian troops have sometimes had to rely on paper maps of Ukraine dating from as far back as the 1960s. Ukrainian troops, taking advantage of U.S. and allied intelligence and operating from the territory they hold in the west that’s not as well known to the invaders, can broadly pummel Russian defenses with longer-range, less accurate Soviet missiles in their arsenal—the Tochka-U, with a range of 74 miles, for example—then deliver HIMARS rockets for a precise hit on a high-value target.

When needed, HIMARS can deliver a lot of those precise hits. Part of what makes it so successful in Ukraine is how quickly crews can reload its rockets. A well-trained HIMARS team can remove a spent missile pod and reload the launcher within five minutes of firing. The most limiting factor are the pods themselves, which are about the size of a small sedan and most often carried in pairs on the bed of a hulking three-axle transport, with another two towed behind on an attached trailer. With that setup, HIMARS crews can fire up to 30 rockets in minutes before needing to resupply.

That pace of fire has contributed to growing concerns over Ukraine’s ammunition supplies. U.S. officials say they’ve provided “thousands” of GMLRS rockets to Ukraine, but that’s a fraction of the country’s needs. A senior U.S. official said in November that Ukraine was firing up to 7,000 artillery rounds daily—from all available weapons, not just HIMARS—as it tries to hold off withering fire from Russia.

Ironically, it was Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 that convinced the U.S. military to increase its inventory of HIMARS at a time when they weren’t in demand. Ferrari credits retired Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster, a former deputy commanding general of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command and, briefly, National Security Adviser under President Donald Trump, with the initial push. McMaster had commissioned a report, called the Russian New Generation Warfare study and published in 2017, that sounded an alarm at the Pentagon.

“[McMaster] essentially came back and said, ‘Hey, land war in Europe is not obsolete,” Ferrari recalls. “And we don’t have any air defense ... and rocket artillery to speak of.”

Military planners acted quickly. The Defense Department’s 2019 fiscal budget request called for a dramatic increase in rocket artillery: 9,733 GMLRS rockets, up from the prior year’s 6,474; 404 ATACMS rockets, more than double the number bought in 2018; and 171 HIMARS launchers, up from just 41 the year before.

The Marines are reducing the number of howitzer batteries and adding more HIMARS-equipped groups, based on the weapon’s success in Ukraine and elsewhere.Alamy

As vital as HIMARS is in Ukraine, the Marines have just one active-duty battalion dedicated to the weapon—the California-based 5th Battalion, 11th Marine Regiment, known as 5/11. In December, the troops took part in the annual combined arms exercise Steel Knight, which unfolds on training ranges, along coastlines, and in the skies around San Diego. During the exercise, two of the Air Force’s C-17 Globemaster aircraft, capable of remaining airborne indefinitely with aerial refueling, flew roughly 500 miles from Camp Pendleton in Southern California to Dugway Proving Ground, Utah. The transport planes inserted a HIMARS team, which hit the ground, executed a six-round mission with practice rockets, and loaded back up for the return journey.

HIMARS is a critical weapon as the Marines seek lighter, more mobile weapons. Already the service has gotten rid of all the heavy tanks it deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, and it’s shutting down several of its conventional infantry battalions in favor of highly maneuverable “littoral regiments” that are built for operating near coastlines. The Marines plan to shutter 14 heavy howitzer batteries in favor of 14 new rocket-artillery batteries, seven of which will be HIMARS units.

In light of this larger strategy, Marine HIMARS operators emphasize arriving swiftly and stealthily and then disappearing before the enemy can identify their missiles’ point of origin. This technique, known as HIMARS Rapid Infiltration, or HIRAIN, would be critical in a fight complicated by the yawning oceans and smaller landmasses of the Pacific, and by the sophisticated reconnaissance and targeting tools of a peer enemy like China.

Some tactics can be remarkably simple: Marines still rely on nets and vegetation to hide launchers from aerial surveillance, for example, or take advantage of walls and buildings in urban environments. Camouflage jobs can resemble art more than science. “When [other people] can’t find the launcher, then we know we did our job,” says Marine Sgt. Adrian Curfman, a HIMARS section chief with 5/11.

Operating despite jammed or intercepted communications presents a more complex problem—something Ukrainian forces are all too familiar with. Standard HIMARS operations rely on GPS positioning and dependable, secure communications between the crew and a fire-direction center. In the future, HIMARS crews may take advantage of the military’s new Mobile User Objective System (MUOS), a narrowband satellite communications network that originated with the Navy and offers faster, more resilient, and reliable worldwide comms.

And later this year, a new HIMARS rocket will enter service. The Army’s Precision Strike Missile, or PrSM, will deliver what manufacturer Lockheed Martin describes as “pinpoint” accuracy at an eye-watering range of more than 300 miles. A 2020 video advertisement from Lockheed, which makes both the munition and the jet, shows a pair of stealthy F-35s approaching a refueling station for enemy aircraft defended by surface-to-air missiles. The jets relay the coordinates to operators on the ground, who then deliver them to a HIMARS battalion located well behind friendly lines. The launcher fires off a twin pod of the 13-foot PrSMs. The first obliterates the refueling station, and the second detonates over the missile site, blanketing the location with explosive fragments.

Though it’s a fictional portrayal, the sharing of data between stealthy jets and ground-based rocket launchers like HIMARS is the type of sophisticated operation we might expect in a future conflict. Countries like Taiwan that seek HIMARS to boost their defenses should not expect them to come with the cornucopia of tactical gifts that Ukraine has enjoyed, including an adversary with flawed intelligence, friendly borders (such as Poland’s) across which to transport weapons, and allies that can provide accurate targeting information. But HIMARS may still have a role to play against a more sophisticated enemy with robust defenses. Its stealth, agility, and range will be required against such an adversary, and current HIMARS operators are demonstrating how the system can become stronger in all three aspects. HIMARS’s secret strength, in fact, may be its adaptability.

No comments:

Post a Comment