LAWRENCE FREEDMAN

Ukraine’s spring offensive has been spoken of with a mixture of anticipation and apprehension for the past few months. The Ukrainians are naturally impatient to get on with the business of pushing the Russians out of their country. But now that spring has come there are doubts about whether they are truly ready for a big push against the Russian occupiers. This war has shown that offensive operations are hard, especially against entrenched and determined defenders. If this offensive falters then it may be difficult to put together another operation with comparable capabilities, and weary international backers, with little more to invest in Ukraine’s fight, might start to press for an unsatisfactory compromise. The messages from Kyiv are mixed. Some insist that the offensive is imminent: others warn that it might be delayed, and perhaps become more of a summer offensive.

The Pentagon Leaks

The numerous slides from Pentagon briefings discovered in a gamer’s chat room provide one source of uncertainty. This episode is embarrassing for the Pentagon. It suggests that too many people, in this case a 21-year-old Air Force reservist, have access to highly sensitive information they really don’t need to know to get on with their jobs but would like to know to show off to their friends. Unlike other countries the US discourages compartmentalisation in intelligence assessments. This is to help analysts join dots that might otherwise have been missed. Unfortunately this also means that when individuals decide to leak material there is plenty to hand.

Leaks like this always make friendly countries nervous about sharing their secrets with the Americans, although another conclusion might be that the American spy agencies are so efficient that they’ll find out anyway. In this respect, the Russians should be especially alarmed about the degree of American insight to their deliberations. The leaks might encourage them to improve their security processes but also demonstrate how much the Americans know, and the detail with which they know it.

Even while deploring the breach of security, commentators still can’t help themselves as they look for insights into the state of the war and in particular how the coming Ukrainian offensive might fare. There are warnings from everyone who has reason to be irritated by the disclosures that they may involve some deliberate disinformation but, with one crude exception where casualty numbers were doctored by a Russian sympathiser, the documents do not appear to be fake. It is always important, however, to keep in mind that just because an analysis has been designated ‘top secret’ that does not make it correct. The classification normally refers to the sources of the information rather than the quality of the conclusions. More importantly, the analyses are at least a month and a half old and in some cases older. The decisions they were intended to shape have since been taken, and in some cases will have addressed the problems identified.

All that being said the overall picture to emerge was not encouraging, largely because of problems with ammunition stocks and air defences and also because of the challenges of introducing promised western equipment into the Ukrainian forces. One assessment from early February warned of significant ‘force generation and sustainment shortfalls,’ and the likelihood that the Ukrainian offensive will result in only ‘modest territorial gains.’ Another from 23 February warned of a ‘grinding campaign of attrition’ that ‘is likely heading toward a stalemate.’

For Ukrainians it is no doubt irritating to learn that the American military are not exactly optimistic on their behalf. On the other hand it can help them explain to their impatient population why rushing into an offensive before everything is in place might be unwise. It also reinforces their pleas to their backers to show more urgency in helping fill the capability gaps identified. And it keeps the Russians guessing, wondering whether this material is really so enlightening or an elaborate ruse to confuse them about Ukrainian plans.

The problems with ammunition stocks has been spoken of regularly, including by the Ukrainian government and certainly by troops on the ground, who have found themselves outgunned as they have to ration stocks of old Soviet ammunition for old Soviet era artillery that is wearing out with overuse. The Ukrainians have also been publicly worrying about air defences for some time. Again the problem is their over-dependence on Soviet-era systems which have been worked intensively for the past six months protecting cities and critical infrastructure from Russian missiles. One document shows that the Soviet-era systems that account for almost 90 percent of Ukraine’s high level air defences were being depleted at rates that would mean that they would now be running out.

There is good news and bad news on the Russian campaign against civilian facilities. The good news is that it now seems to have abated because it achieved nothing of strategic value. The bad news is that this will allow the Russian to make Ukrainian military assets their top priority for missiles, drones, and aircraft. This will pose problems for any concentrations of Ukrainian forces, especially on the move. Russian has also been working on electronic warfare to jam Ukrainian radars to keep their air defences blind. Against this far more capable air defences are now being delivered to Ukraine, including Patriot, and there have been quiet moves apace to scour the world for stocks of old Soviet air defence missiles, as well as ammunition.

Since the leaked assessments were completed there has been a new US assistance package worth some $2.6 billion, including ammunition for Patriot and HIMARS missile batteries, gun trucks and anti-drone laser systems, new air surveillance radars, antiaircraft ammunition and Grad rockets. But the shortages are still a worry. As the Kyiv-based Centre for Defence Strategies observed, they need more ‘EW [Electronic Warfare} systems, anti-aircraft defense systems, artillery shells, heavy infantry weapons (mortars, automatic grenade launchers, large-caliber machine guns).’

The Russian Offensive

The other thing that has happened since the leaked assessments were completed was that the Russian offensive has failed. While the Ukrainians waited for the spring the Russian commanders showed no interest in a winter break. Boggy fields did not preclude fighting in and around the battered urban landscapes of the Donbas - over derelict industrial complexes, shell-marked roads, abandoned apartment blocks, and even rooms within broken houses. These battles have been intense and brutal although they have barely shifted the front line.

I discussed the weaknesses of the Russian offensive in my previous post. To recap, last September, following the successful Ukrainian offensive through Kharkiv oblast, Putin raised the stakes. He claimed a larger chunk of territory than occupied at the time, sought to meet manpower shortages through mass mobilisation, and gave General Sergei Surovokin overall command. Surovokin’s strategy was to stabilise the front by improving defences while concentrating offensive efforts on Ukrainian infrastructure using missiles and drones. With winter over and the Ukrainian electricity grid functioning this effort has clearly failed, and means that capable systems were wasted on targets that hurt Ukraine’s people and economy but did little to impede its military operations.

Meanwhile Surovokin’s success in strengthening Russian defensive positions, including managing the evacuation from Kherson City last November, left Putin unimpressed. His territorial objectives, which remain substantial, were left unmet. Surovokin was demoted last January. Chief of the General Staff, Valery Gerasimov was put back in charge with a view to getting a Russian offensive underway before the Ukrainians could mount one of their own.

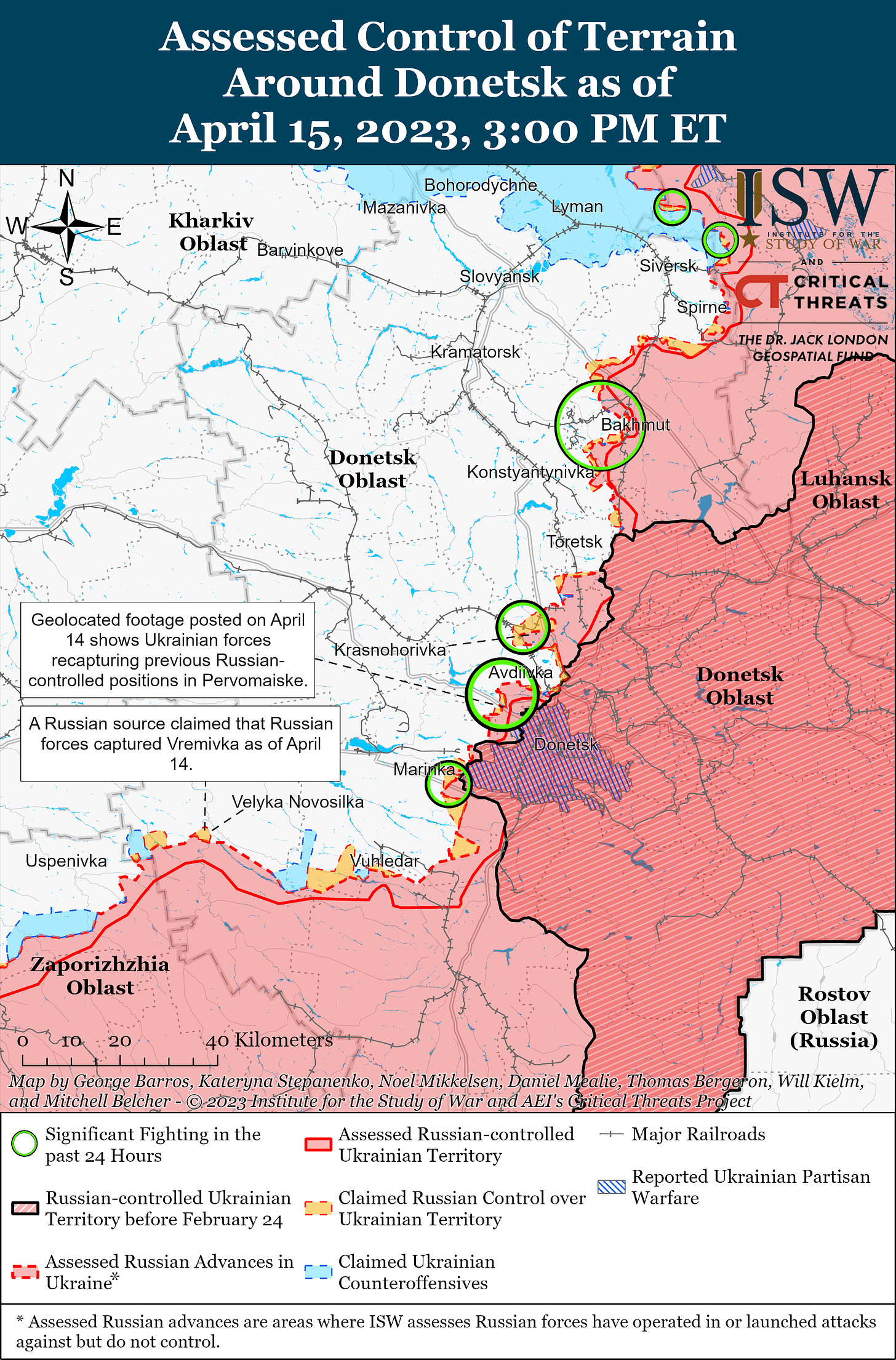

So far there is precious little to show for the huge effort that has gone into this offensive. The main effort still concentrates on Bakhmut, a battle which began almost a year ago and which has been the centrepiece of Russian operations since July. Perhaps a quarter of the city is still in Ukrainian hands, which is too much for the Russians. The mercenary Wagner Group, which took the main responsibility for Bakhmut, has been severely depleted by the effort. It is now concentrating on pushing its way through the centre of the city, while regular forces work the flanks. The most important issue for the Ukrainians is whether they can maintain the security of the main supply route. So long as they can use that they will be content to keep the Russians occupied in a futile and costly quest.

Even if Russian flags eventually fly over the ruins of Bakhmut this would not make for a successful offensive. Dozens of Bakhmuts would have had to have been taken by now, including over cities such as Kramatorsk and Lyman, if Putin’s minimum objective of controlling of all the Donbas was to have been achieved. For detail about how little the Russian armed forces have progressed see this excellent analysis, with accompanying maps, by the New York Times. The other battles that have taken place, have, as with the others, involved targeted cities being pounded and left barely habitable, but at an enormous cost in manpower and, one presumes, morale.

I should say that I am wary about casualty counts in this, as in any other, war. Obvious biases intrude when units from one side lay claim to the damage they have done to the other. On the other hand, casualties in wars such as this are often out of sight of the enemy - the results of illness and accidents, possibly aggravated by poor medical care and poor morale leading to self-inflicted wounds and suicides. It is by casualties that we measure the human cost of war but they do not always provide a good guide to who is winning or losing, as if the cumulative losses can be weighed against each other. After the September mobilization, Russian tactics, after all, assumed sufficient reserves of manpower to enable it to throw relatively untrained and ill-equipped men at Ukrainian positions, propelled forward more by fear of those prodding them from behind as much as those facing them in front.

The real issue is the combat effectiveness of individual units. The Wagner group has lost thousands in Bakhmut and has now run out of convicts to throw against Ukrainian lines. Russian regular forces have been drawn into this battle and are suffering accordingly. The effect of the fighting elsewhere is that some units no longer exist.

Consider, for example, the battle for Vuhledar which began on the night of 24 January when Ukrainian defences were caught out by a Russia attack involving troops under the banner of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the marines of the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade. These marines have not had a good war. They were involved in the war’s early battles for Bucha and Irpin after which they had to be restaffed. Then they were engaged in early November in what members of the brigade described as a ‘baffling’ assault on the Ukrainian garrison in Pavlivka, where again they endured massive losses. The losses were denied by the Russian Ministry of Defence and the survivors who had complained were reprimanded. Nonetheless, the brigade still had to be restaffed again.

In the battle of Vuhledar they were destroyed once more. As the Ukrainians stabilized their position they inflicted heavy losses on the Russians, helped by the ineptitude of the Russian tactics. This was especially significant because of the role played by tanks. Tank battles play an important role in Russian military mythology but their ability to use them effectively has been undermined by heavy losses since the early days of the war (which has been well documented). This was seen as an opportunity for a rare tank assault. On 6 February, 30 tanks and other heavy weapons were destroyed by Ukrainian artillery. This is one account of the battle:

The Ukrainian army’s elite 72nd Mechanized Brigade is entrenched around Vuhledar. It has laid minefields along the main approaches from Pavlivka. Its drones surveil the front. Its artillery is dialed in.

The Russians know this. And the assault force took rudimentary precautions. Tank crews injected fuel into their exhausts to produce smokescreens. At least one T-80 carried a mine-plow.

But leadership and intelligence failures—and Ukraine’s superior artillery fire-control—neutralized these measures. The Russian formation rolled into dense minefields. Destroyed tanks and BMPs blocked the advance. Vehicles attempting to skirt the ruined hulks themselves ran into mines.

Panicky vehicle commanders crowded so tightly behind the smoke-generating tanks that Ukrainian artillery, cued by drones, could score hits by firing at the head of the smoke. The Russians’ daylong attack ended in heavy losses and retreat. The survivors left behind around 30 wrecked tanks and BMPs.

Two days later there was another move forward with similar results. With the 155th Brigade effectively eliminated and the survivors unwilling to engage in any more assaults, other troops were brought in. In a video appeal to Putin, published on 25 March 2023, around 20 members of a unit identified as the Storm Squad from the 5th Brigade of the 1st Corps of the Russian 8th Army, complained about ‘anti-retreat troops’ forcing them to advance, leading to the deaths of 304 of its members, including the company commander, and another 22 wounded. After these costly defeats General Rustam Muradov was demoted in late March from his position as Commander of Eastern Military District.

Another example of the costs of the war, revealed by a reporter for the Washington Post after scouring the recently leaked documents, concerns Russia’s clandestine spetsnaz forces, essentially special forces tasked with high-risk missions that rely on stealth as much as brute force. Of five Spetsnaz brigade returning from Ukraine all but one had suffered significant losses, with one reported to have ‘lost nearly the entire brigade with only 125 personnel active out of 900 deployed.’ Rob Lee is quoted in the piece observing how Russian commanders had used these troops, some of the most capable in the army, to compensate for the weaknesses of the rest of the infantry. As a result, ‘Russia lost all these key capabilities up front that they couldn’t easily replace — both equipment-wise and talent-wise.’ The death of a spetsnaz brigade commander in Vuhledar illustrated the problem. As Lee noted a senior leader that far forward suggested that ‘either losses are too heavy in that unit, or they’re being used in a way they’re not supposed to be used.’

The Ukrainian Offensive

This creates a predicament for the Russian commanders because they must prioritise where they use available troops to continue with their offensive, and how much they keep back for defensive duties, in anticipation of the Ukrainian offensive. Thus while the current Russian efforts concentrate on Avdiika and Marinka along with Bakhmut, the a Ukrainian general recently observed how the need to somehow finish off Bakhmut has led to Russian troops being moved there from Avdiika, which is another operation that remains incomplete.

Of course these past few months have taken a heavy toll on the Ukrainians, with the loss of some of their most experienced troops. They have been seeking to build up the new units for offensive operations separately from those taking the brunt of the current fighting but the effort to prevent the Russians taking Bakhmut is likely to have required some of their reserves. It has been known for some time that Ukraine is assembling 12 combat brigades (each with 4,000 to 5,000 soldiers), of which nine are being trained and supplied by the United States and other NATO allies. According to the leaked documents, six were to be ready by 31 March and the rest by the end of this month. Readiness depended on deliveries. The equipment required for the NATO-supported brigades was more than 250 tanks and 350 mechanized vehicles.

If this is correct we are getting close to the start of the Ukrainian offensive. To work out what to expect we probably need to free ourselves from some natural assumptions about what offensives look like.

The term conjures up images of heroic soldiers charging enemy positions, whether as cavalry with drawn swords, or columns of tanks moving purposefully over churned up fields, or hapless soldiers scrambling out of their trenches when the whistle blows to dash across no man’s land. But instead of frontal assaults, which normally end badly, this campaign might be more subtle, using opportunistic probes to find weak spots in the enemy lines, moving slowly by stealth, creeping up on unsuspecting defenders. They will want to avoid the grind of urban warfare favoured by the Russians, who do not care about the devastation caused, but will instead seek to cut off enemy units from their supplies, encircling them until their troops have little choice but to withdraw in a hurry or surrender. The more robust Russian redoubts may require a preparatory stage of artillery strikes that goes on for days, so that by the time Ukrainian troops move forward they are taking on an exhausted enemy caught among shattered fortifications. Or it might be something else again.

Because we cannot be sure what the offensive will look like we might not know when it has started. After all, there was much talk in February of the coming Russian offensive, only for it to become apparent that it had begun in January. And we should not assume that we know where it will start. We can stare at maps, drawing imaginary lines that split Russian forces in two, and working out clever routes to Crimea. There have been reports of Ukrainian troops preparing to attack east of the Dnipro River in the Zaporizhzhia region of southern Ukraine, and even some recent reports of activity in that area. Others wonder if there may be more opportunities in the Donbas, especially if Russian forces in the region have exhausted themselves. But this is the aspect of the offensive about which it is most important to keep the Russians guessing.

The Russians appear to be most worried about the threat to Crimea. We know of the enhanced Russian defences, involving complex sets of fortifications, with so-called dragon’s teeth, mines and ditches all designed to catch armoured vehicles before they can even reach the defending troops waiting in their trenches. They also seem to be worried about possible incursions into adjacent Russian territory, which would certainly be embarrassing for Moscow although unlikely to be a high priority for Ukraine.

As Kyiv points out regularly, very few people know the actual plans, and these plans might change. So there is little point speculating too much about the when, where, and how. We can be sure only that the Ukrainians are intending to seize the initiative away from the Russians with a number of possibilities opening up once it has been seized. Whatever form the offensive takes the underlying strategic question will remain as before: Can these operations change the course of the war?

Part of the narrative encouraged by the Pentagon leaks is that Ukrainian commanders may not get another chance to win this war. If their offensive achieves as little as Russia’s has done then those who assume that this war is doomed to a continual stalemate will be encouraged and the clamour for an early settlement based on the current division of territory will grow. In this respect the first objective of the Ukrainian offensive is to demonstrate to their international backers that they are worth a continuing investment. That requires liberating a significant chunk of territory. The second, and ultimate objective, is to persuade the Russians to leave.

The standard narrative assumes that the Russians can continue with this war indefinitely because Putin remains firmly in charge and he cannot countenance defeat. Yet Russian strategy has been through a number of shifts and turns through the war and may do so again. Nobody would suggest that Moscow is indifferent to the outcome of these battles. If they were they would not have devoted so many resources to victory or become so fixated on Bakhmut. One can see the need to prioritise having an impact on Russian force dispositions, with a growing sense that they must keep something in reserve to defend their gains. The strategic argument, as far as one can tell, has been won by those who believe that Crimea, and the approaches to it, must be retained at all costs. But does that mean that anyone in the Kremlin can contemplate losing ground in the Donbas when they have spent the last few months trying to occupy even more of this territory? As Mick Ryan discuses in his substack as Gerasimov’s capabilities become stretched he will have some hard decisions to make.

A curious essay by Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin published on 14 April was designed to shore up the hard line faction should Ukraine be successful in its counter-offensive, an event that he seems to think is quite likely. In this essay he argued that should this happen the Russian ‘deep state’ (defined as ‘a community of near-state elites that operate independently of the political leadership of the state and have close ties and their own agenda’) would push the Kremlin to make concessions to end the war quickly though these would ‘betray’ Russian interests. (Some reported versions of this essay make it sound as if he was calling for the end of the campaign but those quotes refer to arguments he was seeking to counter). Prigozhin sees this deep state as having already sabotaged the Russian war effort because its members miss their lives of comfort. Prigozhin warms that there can be no surrender in part because a Ukrainian victory is unacceptable, as this state is now so hostile to Russia, but also because he expects that should Russia lose “radical national feelings” in Russia would be intensified sufficiently to galvanize the nation to come together to defeat Ukraine. This is desperate stuff, confirming that elite opinion is not of one mind on what to do with this war.

Putin and his commanders cannot afford to get many more of the big strategic decisions wrong. If they do so then they will face the prospect of not only futile stalemate but of humiliating withdrawals. I am less convinced than others that they can continue to brush off one setback after another simply because that is what autocratic police states can do, pretending to their people that nothing seriously has gone wrong. Insouciance and misinformation can take you only so far.

No comments:

Post a Comment