Antonia Colibasanu

Borderlands have long been an object of scrutiny in the realm of geopolitics, as they represent a point of convergence, interaction and oftentimes conflict between nations and political systems. The significance of these regions cannot be overstated, as they often serve as a crucible for political and military struggles, as well as a site for intricate diplomatic negotiations and maneuvers. In addition, borderlands frequently witness the interplay of different economic and social systems, giving rise to distinct hybrid cultures and identities.

Classical geopolitical analysis, which focuses on the political, economic and military domains to understand a country’s geopolitical imperatives, has traditionally been ill-equipped to account for the complexities of borderland regions, beyond their geographical location. However, my own research project related to an upcoming book I’m currently writing on the borderlands, beginning with the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, and my work on current events for Geopolitical Futures, have highlighted the diversity of roles played by borderlands in regional and global stability.

Core Borderlands and Geopolitical Nodes

As I delved deeper into the theories of Halford Mackinder, Nicholas Spykman and Alfred Thayer Mahan – all prominent geopolitical thinkers from different eras and political environments – I began to discern a common denominator for the world’s borderlands or, more precisely, the borderlands of the world’s continents. These regions are characterized by their strategic location, distinctive socio-economic features, and sustained interest from major and middle powers seeking to ensure their stability. Indeed, the very stability of these borderlands is paramount, as without it, the risk of war and conflict looms large, threatening to spill over into neighboring regions and potentially reshaping the geopolitical landscape of an entire continent.

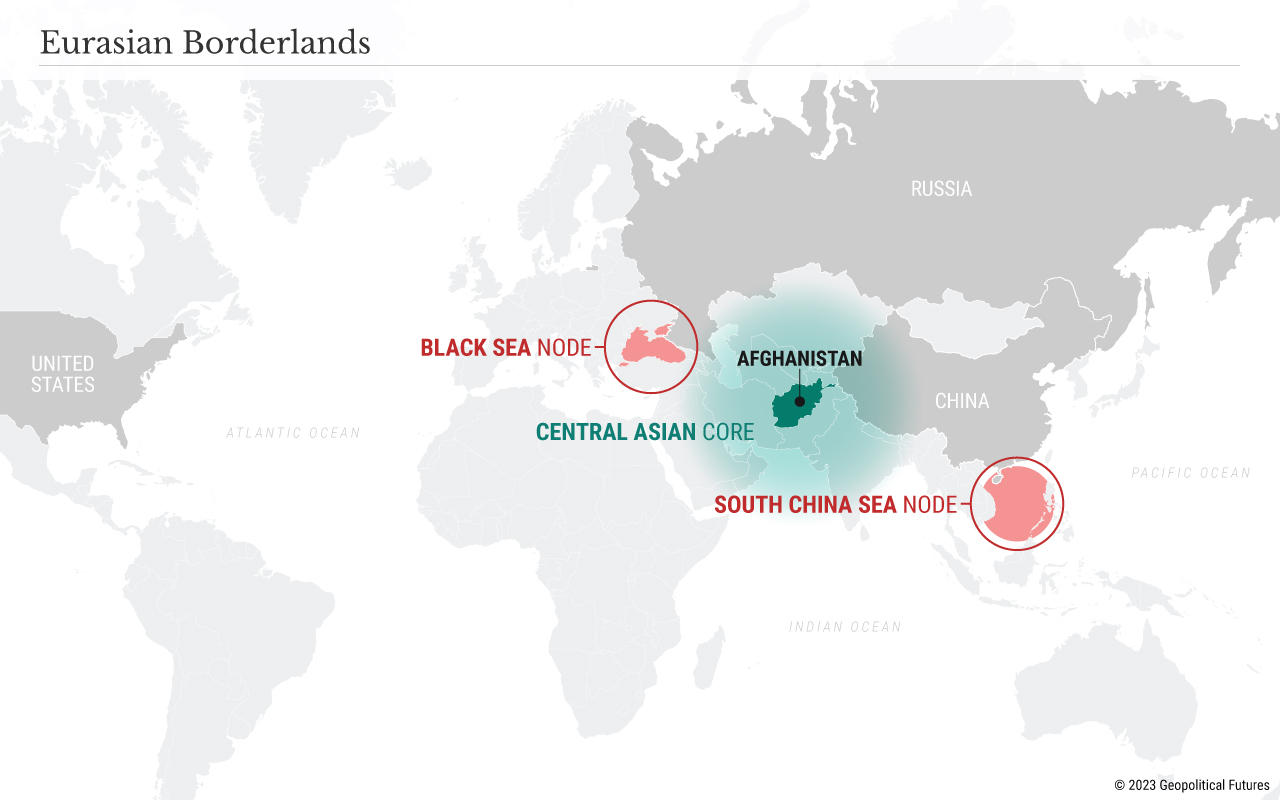

The notion of what I call a “core borderland” emerges as a crucial concept in understanding the stability of the international system. The Eurasian continent’s core borderland is in Central Asia, where the influences of Europe, Russia, China, India, Iran and Pakistan converge, much as it was for their ancestors. Afghanistan is a prime example of a core borderland, as evidenced by the sustained interest of major powers in its stability over time. This is also why Afghanistan can never completely be controlled.

The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan has created a power vacuum in Central and Southwestern Asia, triggering changes that have reverberated across Europe and its borderlands. The timing of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is not coincidental; it follows a sustained period of U.S. withdrawal from the Greater Middle East, not to mention the global pandemic. Meanwhile, other European powers, such as Poland and Turkey, have moved to consolidate their positions in their borderlands. As a result, tensions have risen in these historically vital areas of international trade and investment. I call these areas “geopolitical nodes,” places of strategic importance where two or more regional or global powers meet. Unlike a core borderland, where major powers’ interests collide, a geopolitical node hosts major trade routes that sustain interdependencies between states.

In their theories, both Mackinder and Spykman point to potential geopolitical nodes without necessarily calling them that. Mahan elevated naval power, but by combining elements of their theories, it is apparent that the Black Sea and the South China Sea are Eurasia’s most important geopolitical nodes.

Throughout history, the Black Sea has been a meeting point for empires, facilitating contact between Europe, Asia and the Middle East. It remains a vital hub for regional stability. However, it is also the node most affected by the war in Ukraine. The body of water at the other end of Central Asia is the South China Sea, a relatively recent node that is rapidly growing in importance. The South China Sea is home to a third of maritime trade by value, mostly due to China’s resurgence in recent decades. Meanwhile, over the past decade, in preparation for the war in Ukraine, Russia has sought alternate trade routes to Europe that bypass the Black Sea and has increased its presence in the South China Sea.

The U.S., which remains the classical global maritime and land power, is facing two competitors. The first is a resurgent Russia, a regional land power that is looking to stretch its reach beyond Europe. The second is a new kind of Eurasian competitor, China, which is both continental and maritime.

The core borderland, where they meet, is Central Asia. In this sense, Afghanistan has been the perfect metaphor for how empires clash and coordinate. The nodes of the Black Sea and the South China Sea are balancing off one another as they interact through the strategies pursued by the U.S., Russia and China. The longer the conflict in Ukraine lasts, the more uncertainty there is in the Black Sea waters and the more pressure there is on China, on the shores of the South China Sea, to join the global economic war.

Russia-China Rivalry

Russia has played a quiet but important role around the South China Sea for the past 20 years. Even though it has close ties with Beijing, Moscow has been steadily arming rival claimants to South China Sea waters like Vietnam and, to a lesser extent, Malaysia, while also trying to build defense ties with the Philippines and Indonesia. In addition, Russia has contributed significantly to the development of offshore energy resources in both the South China Sea and the so-called North Natuna Sea, off the coast of Indonesia. While Western energy companies frequently reduced investments in contested areas to avoid conflict with China, their Russian counterparts filled any significant investment gaps. The $400 billion, 30-year energy agreement signed in 2014 between the China National Petroleum Corp. and Russia’s state-owned gas company Gazprom marked the start of Russia’s diplomatic pivot to Asia. It was also the year that Russia invaded Crimea and eastern Ukraine.

In 2001, Russia’s trade with Europe was almost triple its trade with Asia ($106 billion versus $38 billion). In 2019, European trade was $322 billion compared with Asia’s $273 billion. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Europe cut trade and investment ties with Moscow, while Asia embraced it.

Russia’s outreach was especially well-received in Southeast Asia. Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar – its traditional allies in Indochina – stepped up their defense cooperation with Moscow. Over the past two decades, Vietnam alone has spent $7.4 billion on Russian weapons, including cutting-edge fighter jets and submarines. Importantly, the two largest countries in Southeast Asia, the Philippines and Indonesia, looked into extensive defense agreements with Russia. Moscow sent its defense attache to the Philippines for the first time ever, and Russian warships started frequenting Manila Bay. Rodrigo Duterte, the then-Philippine president, made history by becoming the first Philippine head of state to visit Moscow twice, and he actively pursued energy and defense agreements with Russia in 2019.

Additionally, Russian energy firms increased their presence in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone and supported Indonesia’s own energy exploration efforts off the Natuna Islands coast. As a result, in an interesting turn of events, Moscow found itself arming and supporting China’s maritime adversaries throughout Southeast Asia.

Russia tried to lessen the pressure on Beijing by routinely holding joint military exercises with China, spanning the East China Sea, Central Asia and the Far East. Moscow largely agreed with Beijing’s position on both the U.S. naval presence in the region and The Hague’s 2016 arbitration tribunal ruling that invalidated the majority of China’s expansive South China Sea claims.

An enterprising Russia has positioned itself as a dependable third force to both the West and China, taking into account Southeast Asian countries’ innate propensity for strategic diversification. Beijing has largely tolerated its supposed ally’s strategic buccaneering in its own maritime backyard because it wants to keep Moscow on its side, especially in the midst of a raging conflict of its own with the West. But this precarious situation could be drastically changed by President Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine, which has made Russia the world’s most sanctioned country.

The majority of Southeast Asian countries have been appalled by Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, which led to their fateful vote in favor of the U.N. General Assembly resolution denouncing the invasion in 2022. Describing the crisis as an “existential issue,” Singapore, the region’s most developed nation, has imposed unprecedented sanctions on Russia. Others have done the same.

The increasingly complex Western sanctions won’t just make it difficult for Moscow to reach major defense and energy agreements; the country’s growing reliance on China may cause it to withdraw strategically from the South China Sea. Beijing will probably pressure Moscow to refrain from arming and supporting its adversaries in the South China Sea and elsewhere as its power continues to eclipse Russia’s. This would further mean that China will be well-positioned to assert its own sphere of influence in Southeast Asia in general and the South China Sea in particular, at the expense of Russia.

For Europe, the geopolitical node in the South China Sea is distant. However, Russian moves in Asia are likely to trigger a U.S. reaction, especially if they lead to a change in China’s strategy. This would, in turn, directly impact Europe.

Our world is fraying at the edges, beginning in the European borderlands but potentially stretching into Asia. Geopolitical nodes will become only more important as supply chains are reformulated, competition for raw materials grows and technological change fragments cyberspace and more. The most critical nodes are the Black Sea and the South China Sea, where the U.S., Russia and China contend for influence and control.

No comments:

Post a Comment