Akhilesh Pillalamarri

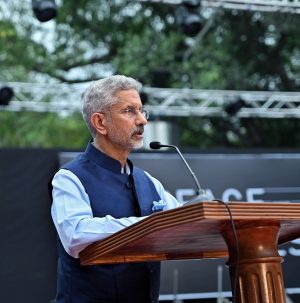

India’s Minister for External Affairs S. Jaishankar, March 29, 2023.Credit: Twitter/Dr. S. Jaishankar

The foreign policy of the United States is not adapting to the challenges of contemporary geopolitical trends throughout the world. In seeking to push for international alignment with its economic and security goals, U.S. policy has instead become counterproductive.

U.S. foreign policy has long sought to prevent any single power from dominating the Eurasian landmass, home to the majority of the world’s population and economic output. While there is no danger of this happening any time soon, U.S. foreign policy has recently alienated both friends and independent-minded allies such as Saudi Arabia, France, and Brazil.

The worldview of the U.S. foreign policy establishment more closely resembles a legal court— w here rules are enforced, and lawbreakers punished in order to encourage compliance from other actors — than a royal court, with its give and take, in which courtiers form and dissolve alliances as needed. This can lead to inflexibility because diplomacy has traditionally been characterized by compromise and the pursuit of national interests. The fruits of this foreign policy have recently been described by the former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Lawrence Summers as being “a bit lonely,” for the United States, “as those who seem much less on the right side of history are increasingly banding together in a whole range of structures.” Summers went on to add that “somebody from a developing country said to me, ‘What we get from China is an airport. What we get from the United States is a lecture.’”

Nonetheless, Summers, like much of the U.S. foreign policy establishment, clings to the notion that the United States is leading countries toward the right side of history, which presumably means a post-nationalist global order based on shared values and free trade.

This notion will increasingly alienate India, a country that Washington has long sought to cultivate as a partner in balancing against China, particularly through initiatives such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. Foreign policy analysts have noted both the increasingly close ties between Russia, China, and India, and their pitfalls, particularly continuing geopolitical and economic tensions between China and India that likely will not be bridged any time soon. But this does not imply that there will be a stronger Indo-U.S. relationship just because of Sino-Indian tensions.

In his book, “The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World,” India’s Minister for External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar explains why. Expressing a view that is common in India, he says that the notion of “a universal and invincible globalized order led by the U.S.” was merely “a transient moment of American unipolarity,” and that the idea of an “end of history” was an “arrogant assertion of an era of hubris” based on a “Eurocentric analysis.” The reason for the return of history, according to Jaishankar, is nationalism, the result of which is an India that can approach the world with more confidence and realism.

There is a deep divergence between the United States and India on both geopolitical questions and values in general. The more the United States tries to get India to align with its positions on these matters, the further away Washington will push India. It goes without saying that India, one of the world’s largest economies, home to a powerful army and navy, and now estimated to be the world’s most populous nation, does not want to play second fiddle to the U.S. or be pressured to accept Western positions on global warming, trade, Ukraine, sanctions on Russia, or other matters.

India, like many other countries outside of the West, does not accept the Biden administration’s framework of the world being divided into competing blocs of democracies and autocracies.

In a recent survey, Indians rated the United States as the second greatest military threat to their country, after China. To a large extent, this perception is not being driven by measured analyses of Asian geopolitics, but by the view of the Indian street that American society and the media simply do not “get” India, and may inadvertently be trying to weaken the Indian state, although this is certainly not the intent of the U.S. government. One such way that this manifests is through U.S. pressure on India to “rethink” its military ties with Russia.

Another such way is the manner through which Western media and activists portray India. Writing in the Washington Post, popular Indian journalist Barkha Dutt notes a “lack of understanding” in Western circles on issues that Indians consider to be grave national security threats, such as the search in Punjab for the extremist militant and preacher Amritpal Singh. Instead, the “emphasis in the West was on the internet shutdown in Punjab while authorities searched for Singh.” According to Jaishankar, the West is not as comfortable with nationalism as India and other Asian countries are and often fails to understand how its policies, even on relatively minute issues, like membership in international bodies, could alienate the Indian public.

In a broader sense, Indian and American societies interpret many values differently. Both, for example, value freedom of speech, but both the formal and social boundaries of this freedom are different in the two countries. According to some global value surveys, India is more likely than the United States to emphasize traditional values over personal autonomy, and this is reflected in legislation and social mores. However, as U.S. foreign policy continues to be values-based, this may cause friction with India and lead to a perception that the U.S. is trying to interfere in India’s domestic politics and social norms.

Despite a shared democratic system and weariness of China, the U.S. and India do not share a similar worldview. U.S. positions on Ukraine and Russia, as well as criticism of domestic developments in India — such as opposition MP Rahul Gandhi’s expulsion from parliament — all continue to alienate India from the United States.

India sees itself as an ancient civilization with a broad influence that is reclaiming its rightful place on the world stage, interacting with other countries as per its interests, and as a country that does not need lessons in how to run its domestic affairs from any other. An American foreign policy that does not respect this risks pushing India away and could contribute to India joining other countries to close ranks against the U.S. in a variety of economic and geopolitical ways.

No comments:

Post a Comment