Innovation from Canon got me into photography, but sadly Canon and its competitors lost their way.

Innovation from Canon got me into photography, but sadly Canon and its competitors lost their way.Selling stock photos in 2005 meant spending big money. Submissions had to meet high technical standards that only expensive cameras could deliver.

One stock agency, for example, demanded 50MB image files — I think it was Alamy. Only pro cameras could create image files that big. Alamy was targeting professionals with medium format cameras.

A medium format camera costed as much as a luxury car. Dream on, I told myself. Alamy was out, and although other agencies were less stringent, everyone had demanding standards.

Then Canon launched the full-frame 5D, which gave me my start on iStock. Technical innovation opened the door for me.

Fast-forward to now, and I’ve a bone to pick with technical innovation. Thanks to ever better cameras on smartphones, the need for fancy cameras to do serious photography is waning.

Or is it? Could it be that Canon, Nikon, and Sony’s incremental innovations in the wrong direction are the real issue? What if they have spent too much time solving yesterday’s problems?

Let’s talk about how the major camera suppliers lost their focus, and what they need to do to help serious photographers catch up with the amateurs.

Camera hardware is the last thing you should care about

According to Statista, digital camera sales have plummeted 87% since 2010.

Why the collapse?

It certainly wasn’t about technical capabilities. Manufacturers such as Canon, Nikon, and Sony have consistently offered better camera technology than smartphone suppliers.

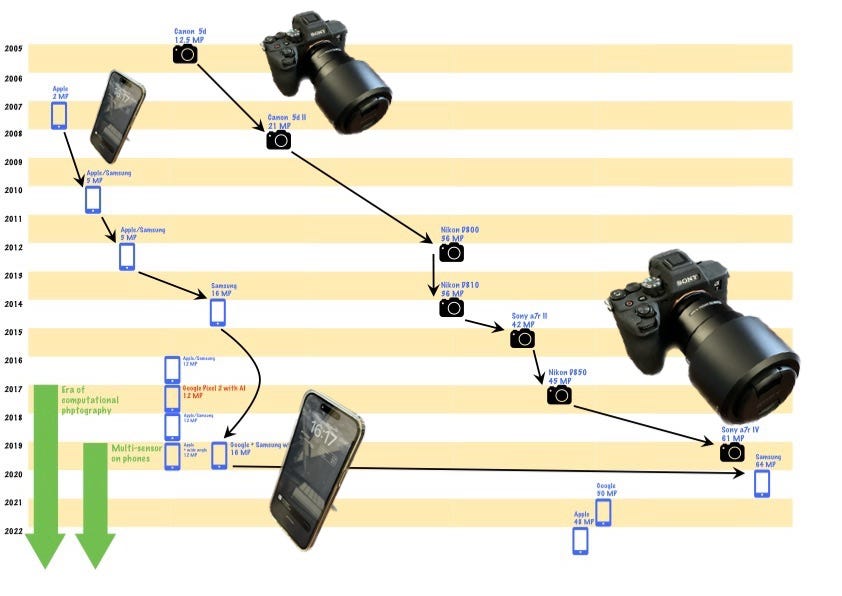

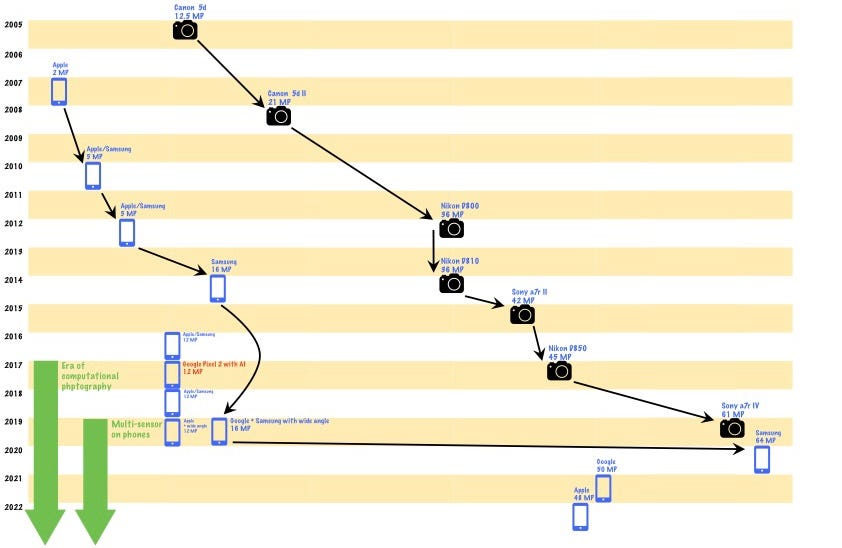

Have a look at the following diagram.

Max Cameras vs Phone Resolution (graph & research by author)

Max Cameras vs Phone Resolution (graph & research by author)Apple, Google, and Samsung have usually been loyal to relatively modest sensors, even when higher resolution sensors were available. In 2014, Samsung launched a phone with a 16 MP sensor, but mainstream phones with 12 MP sensors were still being released in 2019.

It isn’t about price, either. You can buy a Canon 4000D for £334 off Amazon, including the lens. That buys you an 18 MP sensor with x3 optical zoom. You could buy three and still spend less than you would buying an iPhone 14 Pro.

So, what gives? It’s the overall package surrounding the camera that makes the difference. Google, Apple, and Samsung have identified a minimum viable technical product and optimised the customer experience.

It’s easier to take good photos. Better yet, Apple and Google’s photo apps will even identify the best ones and turn them into movies. It’s all done automatically.

The smartphone form factor prevented them from doing anything else in the early years. Apple and Google turned this necessity into a virtue.

Meanwhile, camera manufacturers developed sensors with ever-increasing pixel counts that even many professionals didn’t need. A camera from 2023 is just as difficult to use as one from 2010. It certainly doesn’t pick out the best photos for you.

So, what should Nikon, Sony, and Canon do?

Internet Connectivity

Modern cameras need to be fully integrated into the Internet.

Imagine if the smartphone user experience was like the camera user experience.How would you feel if you had to transfer photos off your iPhone was via an SD card?

How would you like it if you had to keep checking manufacturer websites for software upgrades and fixes?

Consider how much less useful your smartphone would be with no access to real-time information.

Wouldn’t it be great if your camera downloaded the local weather and automatically configured your camera settings? Yes, most modern cameras try to guess what the white balance should be, but why guess? Just check if it’s cloudy.

Or, what if the camera used your latitude, longitude, date, and time to realise that you’re probably taking photos at sunset. It would be handy if the camera looked up the characteristics of that newly launched lens you just bought. It could learn how to compensate for chromatic aberration and vignetting (say).

Camera manufacturers would benefit too. With user permission, they could gather data on which features photographers are using and how often. Instead of trying to guess what users are doing, or attempting to deduce it from a small sample, they could know.

Which neatly brings me to user interface design.

User interface

Think of all the things an iPhone or Google Pixel can do. They enable you to manage email, browse the Internet, run apps, and consume videos and music. Oh, you can also take photos and store them in a library visible from anywhere.

Now consider what a digital camera does. You can take photos with it. Which do you think has the simpler user interface?

Surprisingly, the multipurpose smartphone has by far the simpler user interface. Even smartphones with small screens have a more straightforward user interface than digital cameras.

Even more ironic, the more money you spend on a digital camera, the harder it is to use. Why? Because it does more and offers finer control.

I have been known to make the occasional snarky remark about the Apple user interface design team. The magic they’ve worked trying to reinvent overlapping windows with Stage Manager on iPadOS springs to mind.

They are, however, rank amateurs at bizarre user interface design when compared to digital camera designers. This tutorial gives you a feel for the complexity and mystery of Sony user interface design.

The problem with camera user interfaces is that they are driven by the camera specifications. They enable the photographer to change every camera parameter, which are mind-bogglingly numerous.

That means you have to remember which parameters you have to change (and where to find them) to carry out tasks. What the camera does is hidden away in a maze of menus.

How should it be? The user interface should be organised around what the photographer is using the camera for.

Doing sports photography, for example? The camera should:go into shutter priority;

choose the best ISO for the lighting conditions;

configure autofocus to track fast-moving subjects.

Put the shutter into burst mode.

While it’s at it, the camera should check the amount of available storage space.

You get the idea. There have been many times when I was out shooting landscapes and noticed (say) a buzzard. By the time I’d reconfigured the camera, the bird was long gone.

I’d still want to tweak settings, but I’d want to tweak from a sensible baseline.

Computational Photography

Sony, Canon, and Nikon should embrace computational photography.

They already do lots of clever stuff with their cameras, so it’s not like they don’t have the on-board computing power. The autofocus on my Sony a7 IV is amazing.

However, they don’t use their computing power to compensate for hardware deficiencies. If you’re using a slow lens or a lens that suffers from chromatic aberration, you’re on your own.

Smartphone manufacturers faced hardware issues on a much larger scale. The form factor meant that sensors and lenses were small, which causes all sorts of problems.

They could have decided that smartphone users should be thankful for having a camera at all, but they didn’t. They realised that they could mitigate or even eliminate many of the hardware flaws suing computational photography.

Why can’t Nikon, Sony, and Canon do the same? If you attach an inexpensive lens with chromatic aberration issues, why doesn’t the expensive camera body compensate for it?

It knows which lens you’re using, after all. As new lenses are released, the camera should update its database from the Internet.

Need more dynamic range because it’s a bright day with harsh shadows? The camera should take multiple exposures to build a good photo.

Perhaps it’s also time for camera manufacturers to explore having more than one sensor in a camera body. Why not one suitable for the brighter part of the image and another for dark shadows? Why limit yourself to trying to make one sensor do all?

Final thoughts

It’s all too easy to get caught up in one way of thinking. It can also be hard to accept that market newcomers have a better approach. Those are hard lessons to learn, but often the hardest lessons yield the greatest payback.

No comments:

Post a Comment