Jayson Warren, Darren Linvill, Patrick Warren

On the afternoon of June 25, 1876, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led five companies of the Seventh Cavalry into the valley of the Little Bighorn River, intent on pacifying the Lakota and Sioux encamped there. A veteran of previous campaigns against the Plains Natives, Custer believed he knew the mind of his opponent; he even wrote as much two years earlier in his memoir, My Life on the Plains. He was confident, but, unfortunately for the Seventh Cavalry, overly so. By that evening Custer and hundreds of others would be dead.

In lore, simple hubris is given as the reason for Custer’s defeat, and the same is said about other infamous military losses—from the Romans in Teutoburg Forest to the French at Agincourt. Pointing the finger at pride to rationalize failure may shape a good morality tale or serve to create a useful scapegoat (as Emperor Augustus is said to have declared after hearing of the disaster at Teutoburg Forest, “Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!”), but seldom does it give actionable insight. The fundamental contributing factor to Custer’s predicament is that he did not understand his opponent as well as he thought he did. The afternoon Custer rode into the valley of the Little Bighorn he was outnumbered, outgunned, and unaware of the disposition of his enemy. More fundamentally, he did not understand or appreciate his opponents’ goals or motivations. Custer thought he was fighting the same battle he had fought before and therefore followed an old plan of battle—one he had literally written the book on. But on that day his experience only ensured he was defeated before firing a single shot.

In our current understanding of digital information warfare, we may be making the same fundamental error that Custer made a century and a half ago. But we can apply lessons from Little Bighorn to twenty-first century conflict where “hearts, minds and opinion are, perhaps, more important than kinetic force projection.” A common principle applies to both kinetic warfare and information warfare: understanding one’s adversary must be step one.

The Russian Playbook Problem

While the US military’s bias towards conflict can intellectually impede its ability to conduct operations in the information environment, framing informational conflict with the doctrinal lexicon of physical warfare (e.g., center of gravity, campaigns, objectives, command and control) can assist in avoiding the pitfalls of the past. This is particularly important at a time when adversary nations are turning their focus from the means of war (i.e., solely armed violence) to the objectives of war. After all, in the same way that Clausewitz contends that war is “a continuation of policy by other means” (i.e, wars are fought for political ends) so too does Thomas Rid find linkages between informational conflict and “political warfare.” Consequently, it is paramount to first understand why a country is engaging in informational conflict (for example, the fear, honor, and interest of Thucydides) before attempting to either evaluate the efficacy of their operations or plan appropriate countermeasures.

Understanding a nation’s goals for a campaign gives insight into their tactics, in both kinetic and information warfare. Since 2016 there has been a natural focus on Russia and Russian tactics when discussing digital information operations, with research examining Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) activities dominating the nascent body of academic literature on state-backed social-media trolls. When campaigns from other nations are exposed, the media and policy community suggest those states have used the “Russian playbook.” Russia is not only the standard-bearer by which all digital influence operations are measured, but increasingly the assumed model for what effective disinformation looks like.

But focusing on past Russian tactics is increasingly ill-advised because the arena of information warfare is becoming increasingly crowded and with each new actor comes the possibility of new tradecraft. As a result, the US national security community needs to broaden its understanding of what “effective” digital information operations might look like. Whether it is foreign efforts to sabotage trust in scientific researchers and institutions; Venezuelan manipulation of public sentiment to boost positive perceptions of Russia’s Sputnik-V COVID-19 vaccine; Moscow’s nefarious use of fake fact-checking during the ongoing invasion of Ukraine; China’s covering up of its genocide of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang; or autocratic regimes fortifying domestic control at home, state-sponsored information operations have a wide range of goals. Online disinformation is not one size fits all. Which tactics may be appropriate depends on the goals the actor wants to achieve, and, in turn, different tactics require different measures to evaluate success or failure.

The Russian IRA’s campaign to target the 2016 election (which likely continued through 2018 and 2020) has generally been judged a success. The campaign’s goal was to divide America along ideological lines and to spread doubt and distrust in democratic institutions. Russia’s goals required reaching real users. To do this they created social media accounts which were artisanal in nature, accounts that purported to be part of specific ideological groups. Some of their most successful accounts, for instance, purported to be Black American women and part of the Black Lives Matter movement. It was necessary for the IRA to build accounts that appeared and acted in every way genuine. The IRA studied and understood the communities it engaged with and was able to seamlessly integrate itself into a group. IRA accounts engaged with genuine users, gained followers over time, and used those followers to pull supposedly like-minded individuals to believe information they were likely already inclined to believe. The success of the IRA campaign can be (and has been) measured by a variety of metrics related to these goals, including organic followers, organic shares, appearances in media, and the successful amplification of targeted narratives in the public conversations. By every measure the IRA was excellent at what it did.

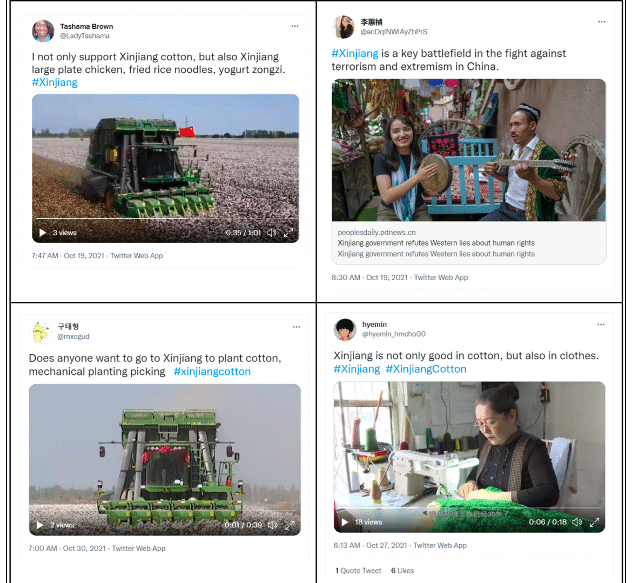

Figure 1. Controlling the Xinjiang Narrative Via Hashtag Flooding

The Little Red Playbook

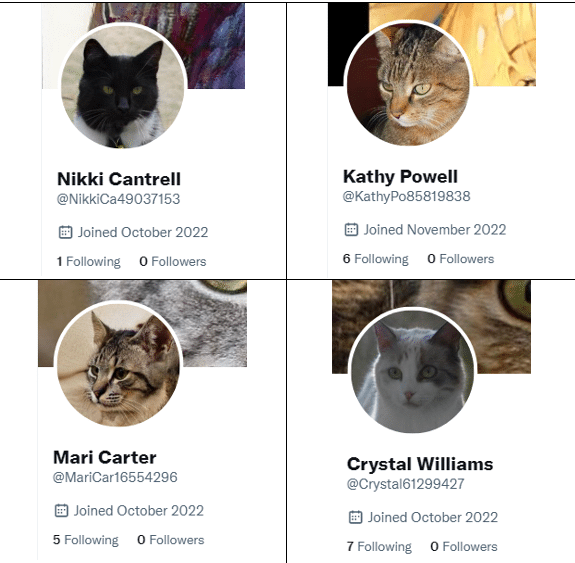

If we examine some digital information operations known to originate from the Chinese state by these same measures, we might conclude that what China has done is not nearly so effective. Social media accounts attributed to China and working to influence the West often appear sloppy or superficial. Seldom do they create accounts with robust persona able to stand up to scrutiny. They often appear fake at a glance. The names and profile pictures regularly have mismatched genders, the handles are a string of algorithmically generated numbers and letters, and the English (or French, or Korean, etc.) is obviously translated by a computer. Chinese campaigns typically, therefore, acquire virtually no organic followers and have minimal audience engagement. Measured by the Russian yardstick, China has failed dramatically.

Much of the research and policy community has made just this judgment. It has been suggested that Chinese digital information operations targeting the West are “more simplistic,” “more primitive,” or “still improving” relative to Russian efforts. Researchers have argued that China has not done the psychological and ethnographic research needed to create convincing Western social media personas. Looking for explanations for this pattern of many thousands of social media accounts attributed to China with little organic reach, it has been suggested that the real goal of Chinese disinformation is not about engagement, but rather to “demonstrate to superiors total commitment by generating high levels of activity (in this case, hitting targets for post counts), while actual efficacy or impact may be secondary.” These arguments assume China’s goals are best accomplished using tactics found in the “Russian playbook” and are grounded in the theory that China’s efforts should involve engagement with real users. They also assume that the adversary in this case is unsophisticated, which was perhaps another of Custer’s mistakes.

There is ample evidence that, at least in many cases, organic engagement may in fact be detrimental to China’s digital operation goals. In just one recent example occurring in the run up to the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, thousands of social media accounts attributed to China began posting the hashtag #GenocideGames, a hashtag used by activists to link the Olympic games to Chinese atrocities committed against the Uyghur Muslim minority in Northwest China. These accounts did not try to engage in conversation or make the hashtag artificially trend so that more users would see it. Far from it. They engaged in what is often called “hashtag flooding,” posting in volume to dilute the use of the hashtag, to ensure that genuine users have a more difficult time using it to engage in real dialogue. Users trying to use the #GenocideGames hashtag for its original purpose were more likely to find meaningless content posted by Chinese trolls and less likely to find content critical of the Chinese state. Russian-style engagement would, in fact, hamper the goal of flooding out narratives critical of China in this way.

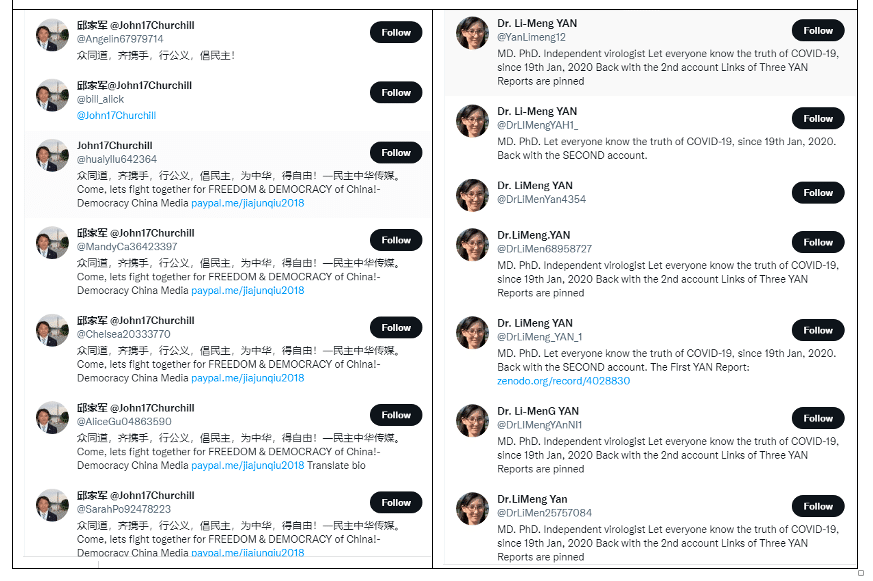

Figure 2. Spoofed Twitter Accounts to Minimize Problematic Expatriate Followership/Accessibility

The Chinese have applied the flooding technique to many different targets, in many different languages, across a large variety of platforms. The targets have included hashtags used by critics (#XinjiangCotton, #Accelerationism, #Safeguard) and the names or handles of critics, especially expatriate Chinese critics (#LiMengYan, #GuoWengui, #邱家军), and the names of disputed or troublesome territories (#HK, #taiwan, #Xinjiang). The flooding has occurred in (at least) Chinese, English, French, Korean, and Japanese, and has occurred across hundreds of international websites and social-media platforms. It included tens of thousands of posts, from thousands of profiles, across many months. In addition to flooding hashtags, they also flood identities—creating hundreds of spoof accounts mirroring individuals critical of China. When successful, flooding obscures all organic conversations. Searching for flooded narratives and targets is difficult because content is dominated by the flood and any new organic messages on targeted topics quickly get pushed down the feed, making organic discourse very costly and inefficient.

Moreover, hordes of spoof accounts make posts from any real account difficult to identify, effectively obscuring valid or legitimate messages from potential readers. The second order effect is to dissuade organic participants from contributing to the targeted conversations. The stifling of narratives and organic online discourse has real consequences and measurable impacts—shutting down content on topics targeted by a motivated political actor is one way to stifle dissent. Therefore, using the “Russian playbook” as the standard bearer and relying on the metrics used to measure Russian online influence campaigns is not helpful because the right measures to determine the impact of Chinese online influence campaigns are not numbers of retweets or likes. Instead, with Chinese efforts, focus should be on the harder problem of measuring the shortfall in organic content or views of that content and what that means for political discourse.

Figure 3. Example PRC “Low Quality” Social Media Profiles

Don’t Judge a Playbook by its Cover

China is not the only actor with designs in the information space that diverge from the “Russian playbook.” A recent (and ongoing) review of 113 foreign and domestic online influence efforts documents 28 distinct influence actors operating over the past decade. Among these campaigns, they identify six broad classes of political goals: discredit, hinder, polarize, spread, support, and influence. They also identify five specific tactics (bot, troll, hashtag flooding, information stealing, fake social media profile) and one catchall for “other strategy.” One could quibble about these particular categories, but they do demonstrate a substantial and important heterogeneity across these campaigns. As one would expect from adversaries matching their strategies to their goals, the tactics and aims correlate, and both vary by attacking country and over time.

Ultimately, the best way to fight influence operations is by setting normative conditions for the truth to flourish and thrive. Towards that end, the national security apparatus should avoid prioritizing threats based on a perceived level of sophistication or tradecraft but rather through a holistic and diversified portfolio that addresses the spectrum of tactics, techniques, and procedures our adversaries employ. Just as any artillery operator understands “low-tech still kills,” so too must information warfare professionals avoid disproportionately emphasizing biased ideas of sophistication over substantive and coherent evaluation strategies. Rather than simply condemn the Chinese behaviors, they should be treated no different than Russian threats and considered for asset freezes, criminal indictments, and even offensive cyber actions. Ultimately, the only viable path to avoiding Custer’s Last Tweet is one whereby information warfare professionals evaluate effectiveness solely on the basis of whether or not it accomplishes an adversary’s goals. In order to do so, however, they must first know their adversary and their goals.

2000 years before Custer’s final battle, Sun Tzu asserted in The Art of War, “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.” Obviously Custer should have considered this timeless piece of wisdom before Little Bighorn, as should Quintilius Varus before marching into the Teutoberg or Charles d’Albret at Agincourt. But they are also words that should be appreciated in whole new contexts that none of those leaders could have imagined. Understanding the mind and goals of an adversary is as important in the digital information environment as it is in any other domain of warfare. Different goals and contexts necessarily require different tactics. Not everyone is following the same playbook, Russian or otherwise. Why would they? They are all fighting different battles.

No comments:

Post a Comment