Agustin E. Dominguez, Ryan Kertis

“As we face complex challenges that span across borders, our success will depend on how closely we work with our friends around the world to secure our common interests and promote our shared values.”

– Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III, Message to the Force, March 2021

Campaigning through cooperation is paramount to implementing the 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS), particularly in lower priority theaters. When the Department of Defense (DoD) transmitted the NDS to Congress in March 2022, it included an unclassified fact sheet that describes a strategic environment identifying China as the United States’ pacing challenge; the acute threats posed by Russia; persistent threats that include North Korea, Iran, and violent extremist organizations; and transboundary threats including climate change and pandemics. In other words, the United States cannot make every region a defense priority. Indeed, the unclassified NDS fact sheet is clear that the Indo-Pacific and Europe are the top priorities. While the fact sheet also makes reference to Central Command with its inclusion of Iran, it fails to mention US Southern Command or Africa Command.

The NDS further identifies integrated deterrence, campaigning, and actions that build enduring advantages as the three primary ways for the DoD to advance its goals. Partners and allies anchor this strategy: they are force multipliers and contribute to the enduring strength of the United States. The Army is well-positioned to leverage existing legal frameworks while applying current doctrine to best campaign through cooperation to provide the US Army access and influence, ensuring that land power remains critical to the Department’s efforts to outcompete China.

What Does Cooperation Look Like?

Joint Doctrine Note 1-19 (JDN 1-19), Competition Continuum, describes campaigning through cooperation as “a purposeful activity to achieve or maintain policy objectives.” Campaigning through cooperationcan build enduring advantages for the Joint Force and establish a resilient partner nation ecosystem that contributes to integrated deterrence. Ultimately, campaigning through cooperation provides the US Army with unique access to operational environments and partner forces that are necessary for maintaining elevated levels of readiness. Thus, establishing enduring relationships through cooperation gives the Army and the Joint Force benefits as it moves along the competition continuum.

The reduced number of warfighting assets and allocated units in lower priority theaters make security cooperation programs, including State Department-funded security assistance programs, the main tools to integrate the contributions of allies and partners. In fact, General Mark Milley, then Chief of Staff of the Army, remarked in 2016 that “we are most successful when we fight as part of a combined multi-national team. While our Armed Forces will always be capable of fighting alone, our priority is to fight together.” Yet security cooperation activities are typically reduced to experiences with security force assistance or greater desire for advise and assist missions. As DoD dedicates less and less resources to these lower priority theaters, channels for communication and action atrophy and steadily dilute in their effectiveness throughout the interagency environment.

Still, there is valuable legal and policy infrastructure to salvage in this space. Notably, a pre-existing legal framework that guides security cooperation activities should be the foremost organizing principle for campaigning through cooperation. For DoD programs, the Fiscal Year 2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) aggregated disparate authorities to streamline security cooperation planning and fundamentally changed the Department’s approach to security cooperation. Under this new framework, DoD conducts security cooperation activities that range from key leader engagements, exchanges, and technical training to large-scale combined exercises—otherwise collectively known as campaigning.

For the Department of State, security assistance programs are necessarily nested within the foreign policy objectives of each respective region and country. These programs include traditional assistance activities such as professional military education and training at US-based institutions and US-funded grants via foreign military financing. To be sure, the ongoing war in Ukraine best captures how both the State and Defense Departments have synergized their efforts within the last decade to professionalize, modernize, and prepare partner nation forces to defend their country.

Doctrine Meets Law: A Framework for Competition

Campaigning through cooperation inherently means the Army must rely on existing security cooperation authorities to make progress on policy objectives. Prior to the 2017 NDAA, a patchwork of authorities existed that enabled the Department of Defense to support myriad disparate programs to address counterterrorism, counternarcotics, and other cooperation activities. These authorities were born out of the post-9/11 reaction to make the DoD more responsive to the emergent threat of terrorism overseas. Combatant commands executed theater security cooperation and provided capabilities to a partner nation while also providing operational support to sustain it to best support counterterrorism objectives. Through the lens of the Army Operations Process, the combatant commands could remain in a prepare-execute-prepare-execute cycle so long as that capability continued to serve US interests and funding was available. Generally speaking, this era was marked by a myopic emphasis on tactical results, not partner nation capacity or US Army access and influence.

But after nearly two decades of global conflict and poor results in the Middle East and Central Asia, Congress passed the 2017 NDAA, ushering in the greatest reforms to security cooperation since the passing of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961. The most notable change was the onset of Title 10, Chapter 16: Security Cooperation. Here, practitioners can find the principal authorities available to conduct theater engagements, DoD-led train and equip programs, and the authority that permits the DoD to train alongside partner nations, an essential component of maintaining proficiency working with partner forces while campaigning. These are just a few examples of authorities the Army leverages in chapter 16.

While a suite of legal authorities remains available to conduct a wide range of activities, security cooperation professionals at all echelons can turn to Army fundamentals captured in Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 5-0: The Operations Process to plan programs. As a result, combatant command campaign plans and subsequent theater security cooperation plans will have a deliberate planning component targeting specific objectives, as opposed to disparate engagements that do not promote integrated campaigning for the Joint Force.

The Operations Process: A Deliberate Approach to Campaigning through Cooperation

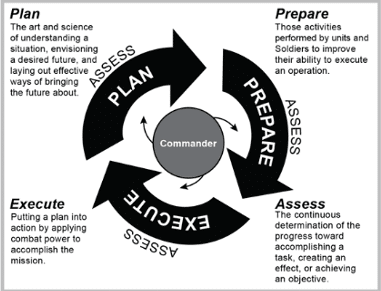

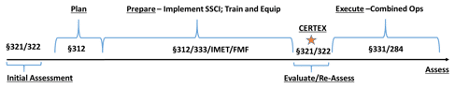

The Army Operations Process provides a helpful structure for implementing the legal framework available to the DoD. Although campaigning occurs at various echelons and security cooperation nests tactical activities for strategic effects, the operations process provides a doctrinal reference point for bridging these activities. ADP 5-0 defines planning as “the art and science of understanding a situation, envisioning a desired future, and laying out effective ways of bringing that future about.” The 2017 NDAA reforms and JDN 1-19 require a departure from the “prepare-execute” approach to successfully campaign through cooperation. The operations process describes fundamentals for effective planning, preparing, executing, and assessing operations, which are the essential aspects of proper security cooperation programing to support the partner nation from inception to full operating capability. Once that capability is achieved, it is critical that the partner provides a return on investment by conducting operations in support of US security interests, including multinational exercises that benefit US Army training objectives and bolster a culture of sustained interoperability.

Figure 1: ADP 5-0 Operations process

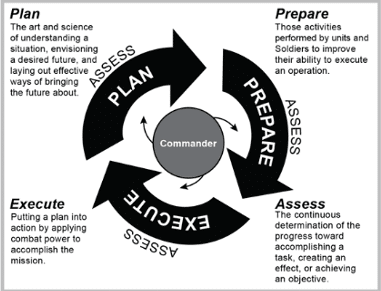

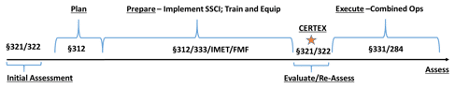

Approaching campaigning through cooperation via the Operations Process requires a change in mindset from implementing annual, individual security cooperation programs to planning holistic, multi-year programs to achieve campaign objectives. Security cooperation professionals at every echelon of the DoD Security Cooperation network must understand their role in the operations process and how it applies to campaigning. By getting back to the basics, the Army may use established doctrine as a roadmap to leverage the legal framework in support of campaigning through cooperation. As a result, security cooperation initiatives will grow the Army’s land power network while simultaneously fostering partner nation capabilities, improving US Army readiness, and implementing the NDS. The following describes how legal authorities can be layered within US Army doctrine:Plan: Pre-operational activities within §312, often referred to as Traditional Commander’s Activities, permit the DoD to fund the personnel expenses necessary for security cooperation. This commonly includes exchanges, planning meetings, and key leader engagements that are necessary for theater security cooperation.

Prepare: Preparing partner nations to train or fight alongside US forces requires the longest planning timeline to implement. Title 22 Foreign Military Financing, International Military Education and Training, and §333 Train and Equip are available tools, yet often require more than one year to plan.

Evaluate/Re-Assess: Leveraging security cooperation to bring US Army units to a “trained” status is critical to campaigning through cooperation and demonstrates the US commitment to partners while benefitting from the access created by deploying units abroad. Here, §321 and §322 can be used to evaluate and certify partners through combined exercises while developing US Army tactical tasks.

Execute: Once a partner force achieves full operational capability, combatant commands can turn to operational support authorities to enable combined operations with, or in lieu of, the US Joint Force. §331, for example, authorizes provision of logistics support, supplies, and services to friendly foreign countries that are conducting Secretary of Defense-designated operations, or a military or stability operation that benefits US national security interests.

Assess: A defining characteristic of the security cooperation reforms of 2017 was the legal mandate to conduct assessment, monitoring, and evaluation (AM&E). AM&E occurs continuously throughout the lifecycle of a program. Inherent to the operations process is the “assess” function that leaders at all levels apply throughout the training and operations cycle. Applying a more flexible, rapid, and qualitative assessment will provide the combatant commands and the US Army the ability to respond to emergent needs and to shift or terminate programs that are untenable.

Figure 2: Example cycle, does not illustrate all possible authorities to use.

Campaigning through cooperation in low priority theaters will require creative solutions on behalf of combatant commands and theater armies. Despite numerous arguments that the DoD is ill-equipped to out-compete, the inverse appears to be true. The tools are readily available for the Army to employ multidomain solutions in cooperation with partners to compete in all regions. In general terms, the operations process is already inherent to the basic implementation of security cooperation programs and this approach will grant those under-resourced regions the ability to prioritize operations, activities, and investments appropriately. A return to the post 9/11 era engagement plans and hyper-focus on tactical results will not suffice in the current environment.

Rather, planners must make a deliberate attempt to incorporate theater security cooperation activities to shape how the Joint Force will campaign through cooperation. ADP 5-0 does not only serve as a guide for conducting operations against the enemy. It can also serve the Army and the DoD in campaigning, through security cooperation, to achieve and maintain enduring advantages for the Joint Force, enable credible, integrated deterrence when required, and build partner capacity to operate with or in lieu of US forces in support of key US objectives.

Lt. Col. Agustin E. Dominguez, US Army, is a foreign area officer (FAO) currently serving as the US Army War College Fellow at the Brazilian National War College in Rio de Janeiro. He previously served in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy. He holds a BS from the US Military Academy and an MBA from Florida International University. As a FAO, he has also served as chief of the Office of Security Cooperation at the US Embassy in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, as the assistant Army attaché in Bogota, Colombia, and as a political-military officer in the Strategic Plans and Policy Directorate, J-5, Office of the Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff. Prior to becoming a FAO, Dominguez served with the 82nd Airborne Division and the 173rd Airborne Brigade.

Maj. Ryan Kertis, US Army, is a foreign area officer (FAO) currently serving in the Office of Defense Coordination in Mexico City. He previously served as a regional security assistance officer at the United States Southern Command and with the Security Cooperation Office in Santiago, Chile. He holds an MA in Latin American studies from Stanford University and an MA in diplomacy from Norwich University. Prior to becoming a FAO, Kertis served as an infantry officer with the 25th Infantry Division and 7th Infantry Division and completed tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

No comments:

Post a Comment