Alex Hollings

With its sights set squarely on countering Chinese threats in the Pacific and Russian aggression in Europe, the U.S. now has at least five secretive new warplanes in development. These programs range from next-generation air superiority fighters that will fly amid a constellation of AI-driven support drones to dual-cycle scramjet-powered hypersonic strike drones very similar to the long-awaited SR-72 concept.

With new multi-static anti-stealth radar arrays and more advanced integrated air defense systems continuing to come online, the U.S. Air Force has stated that it believes even the mighty F-22 Raptor will no longer be survivable enough in near-peer contested airspace as soon as 2030. The Raptor is widely considered to be the stealthiest fighter ever to take to the skies, so the broader context one can glean from concerns about its survivability is clear: the U.S. needs a slew of new offensive and defensive warplanes it can rely on to dominate the skies over its opponents. These warplanes will also have to defend our own airspace against a sea of new stealth fighters and bombers being hurriedly developed by Russia and China.

In order to meet the combined threat of new air defenses and increasingly potent enemy warplanes, the U.S. now has two different but deeply connected stealth-bomber programs at some stage of development, alongside two similarly connected stealth-fighter programs. But perhaps the most secretive of all of these new programs is an Air Force Research Laboratory effort to field fully-functioning dual-cycle scramjet engine systems for a low-observable hypersonic drone designed to fly three different types of combat missions.

1) NGAD: The US Air Force’s next air superiority fighter will come with its own drone wingmen

US Air Force NGAD stealth fighter render.

The F-22 Raptor is widely seen as the most capable air-superiority fighter on the planet, but with fewer than 150 combat-ready airframes left in service, America’s apex predator of the skies is an endangered species. That’s where the U.S. Air Force’s NGAD program comes in.

Unlike other efforts to field new warplanes, NGAD isn’t aiming to develop a single jet, but rather a whole family of systems that can be spread across multiple airframes, including a bevy of support drones that will fly alongside the crewed fighter. This new family of systems will specialize in air combat with the stated aim of dominating enemy airspace. However, like all modern tactical aircraft, it will have multi-role capabilities that will allow for air-to-ground engagements as well.

NGAD is expected to lean further into current aviation trends of cockpit automation and data fusion, taking many of the more monotonous or complex flight control functions out of the pilots’ hands to allow them to focus on the fight, especially while directing support drones to engage air or surface targets on the fighter’s behalf. While not confirmed, it’s expected that the NGAD fighter will leverage now-in-development adaptive cycle engines for increased thrust, improved fuel economy, and a dramatic jump in thermal management (and as a byproduct of that, more energy production for advanced systems like directed energy weapons).

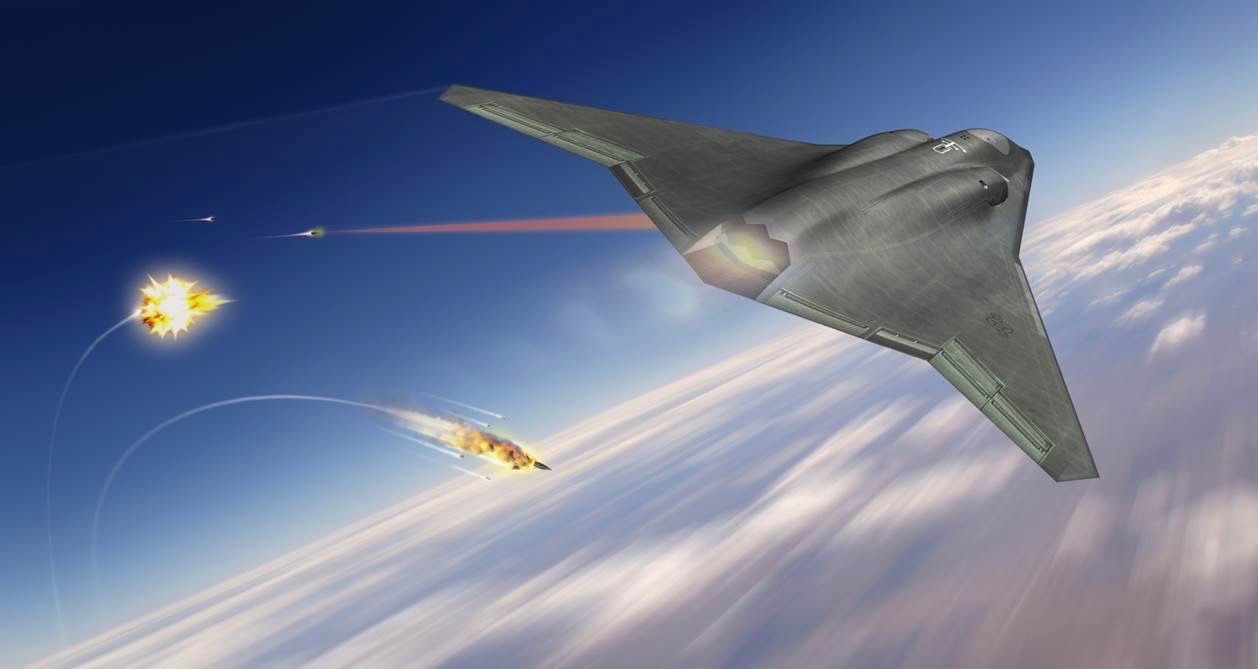

An artist’s rendering of NGAD.

An artist’s rendering of NGAD.In 2020, it was announced that a full-sized technology demonstrator for the NGAD program had not only already been flown, but had even broken multiple records. While it’s important to note that a technology demonstrator is not the same thing as a flying prototype and may not even look like the new air dominance warplanes the U.S. will eventually field, it sounds as though the NGAD program is progressing at full speed.

The expected sticker price for America’s new NGAD fighters will likely begin at around $200 million per airframe. Its support drone costs are expected to range wildly from attritable low-cost platforms like the Kratos XQ-58 Valkyrie, at around $1.3 million apiece, to fully-functioning unmanned stealth fighters at a per-unit cost of around $100 million which is greater than the F-35A’s per-unit cost. That may sound pretty steep, but it’s worth noting that America’s F-22 Raptor, which saw price increases due to the abrupt cancellation of the line, ended up ringing in at around $337 million per jet (when rolling development costs into production) in 2011 dollars. That’s a whopping $442 million today. The Air Force has stated that it does not intend to purchase NGAD fighters as 1:1 replacements for the F-22, so the total number of fighters this program will deliver remains uncertain.

2) B-21 Raider: The US Air Force’s next stealth bomber will sneak past radars that can even spot stealth fighters

A rendering of the B-21 Raider. (Northrop Grumman)

Despite its sleek, futuristic aesthetic, Northrop Grumman’s B-2 Spirit stealth bomber has now been in service for more than a quarter-century. Now, as China and Russia continue developing their own B-2 competitors, the firm is looking to expand America’s lead in this field with the B-21 Raider that is currently in development.

The B-21 will draw heavily from the B-2’s successful flying-wing design that Northrop has long specialized in, yet will be a fair bit smaller, carrying an anticipated 30,000-pound payload into the fight, rather than the B-2’s impressive 60,000. Despite the shrinkage, the B-21 will still be rated to carry just about every nuclear and conventional munition we’ve come to expect out of America’s bomber fleets, while leveraging stealth technology said to be at least “two generations ahead” of the famously sneaky B-2.

A rendering of the B-21 Raider. (Northrop Grumman)

Unlike stealth fighters, which are detectable (though not targettable) using low-frequency radar bands, the flying-wing design leveraged by both the B-2 and B-21 is said to be extremely stealthy against all radar frequencies. This makes these long-range bombers perfectly suited for strike operations in a heavily contested airspace in the initial days of conflict. If a war were to break out with China, for instance, it would almost certainly begin with U.S. stealth bomber fleets engaging anti-ship defenses on Chinese shores to allow aircraft carriers to close in.

Today, there are at least six B-21 Raider airframes in some stage of production, and unlike most clean-sheet builds for new warplanes in U.S. history, the Raider is expected to conduct its first test flights with all its mission systems already installed and operational. If all goes well, that will dramatically reduce the time between first flight and initial operating capability. The U.S. Air Force capped the per-unit price for its new stealth bomber at $550 million per airframe in 2010, which when adjusted for inflation, puts the Raider’s anticipated cost at around $729.25 million each. That figure might make your eye twitch, but the U.S. is said to have spent as much as $2 billion each on its original stealth bomber when rolling R&D costs into procurement.

3) F/A-XX: The US Navy’s new stealth fighter will share systems with NGAD while delivering a huge jump in range

A rendering of a potential F/A-XX design. (Boeing)

A rendering of a potential F/A-XX design. (Boeing)After decades of trying to force every fighter the U.S. has ever developed into carrier duty culminating in the acquisition nightmare that has been the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, the U.S. Navy’s next stealth fighter is being developed specifically to thrive on America’s flattops.

Being developed under the name F/A-XX, the “F/A” prefix indicates that this new aircraft will be expected to not only deliver multi-role capabilities like all modern fighters but will also be expected to excel at both air-to-air and air-to-ground combat operations. The U.S. Navy and Air Force have both indicated that the stealth fighter to emerge from the F/A-XX effort will share some common systems with the NGAD program, which will allow this new fighter to be fielded more rapidly. That will also mean the Navy’s next jet will benefit from the same modular software and hardware architecture intended to allow for frequent low-cost updates to these aircraft as technology matures around them.

A Boeing rendering of a potential F/A-XX design.

A Boeing rendering of a potential F/A-XX design.Aside from the requisite boost in stealth and data fusion capabilities the U.S. prioritizes in new fighter programs, the Navy’s F/A-XX will also need to deliver a huge increase in fuel range over the Super Hornets and F-35Cs currently operating at sea. China’s area-denial bubble, or the area of the Pacific that falls within reach of China’s advanced hypersonic anti-ship missiles like the DF-ZF, now extends more than 1,000 miles from Chinese shores, while Navy jets like the F/A-18E and F-35C have a combat radius of only around 650 miles. That means American carriers cannot sail close enough to China to fly combat sorties without placing the carriers themselves at risk of being sunk.

The F/A-XX is expected to address this capability gap by leveraging both larger fuel stores and the aforementioned more-efficient adaptive cycle engines likely destined for the NGAD, while also benefitting from mid-air refueling provided by carrier-based MQ-29 drones. The Navy has not yet released cost estimates for this fighter, but it will likely ring in at a comparable price to the NGAD.

4) Wingman Bomber: The US Air Force’s B-21 Raider will fly with an extremely advanced drone stealth bomber

A rendering of a B-21 Raider Drone Wingman (Created by Alex Hollings)

A rendering of a B-21 Raider Drone Wingman (Created by Alex Hollings)During a keynote speech delivered at the Air Force Association’s 2022 Warfare Symposium earlier this year, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall revealed that the United States is exploring the idea of an uncrewed stealth bomber platform that could fly missions ahead of the optionally-crewed B-21 Raider to expand upon America’s deep penetration strike capabilities in hotly contested airspace. This new bomber platform would be expected to have a “comparable range” to that of the new globe-spanning bomber, with payload capabilities to be determined in large part by price point… which is currently estimated to land somewhere near the incredible figure of $300 million or more per drone.

An unclassified Request for Information the Air Force has released to industry partners calls for this new drone stealth bomber to have at least a 4,000-pound payload capacity and a combat radius of 1,500 miles. Yet, as Aviation Week’s Steve Trimble has pointed out, it seems likely this aircraft will need to be able to match the B-21’s range in order to serve its purpose as a means of support on long-duration missions.

A B-21 Raider Drone Wingman rendering. (Created by Alex Hollings)

A B-21 Raider Drone Wingman rendering. (Created by Alex Hollings)A substantially cheaper drone stealth bomber that can fly ahead of the B-21 Raider could offer a huge strategic value. Raider crews could use these uncrewed bombers to target anti-ship weapons that are too well defended to risk engaging crewed aircraft, or they could engage air defense systems to allow for a safer route to the objective. Of course, at half the cost of a B-21, we’re still talking about a drone stealth bomber that costs as much as three or more F-35s. Nevertheless, the F-35 very likely couldn’t reach these targets, to begin with, whereas these new drone stealth bombers will be able to.

With the B-21 expected to replace both the B-2 Spirit and the B-1B Lancer, it makes sense for the U.S. to consider fielding less-expensive drone stealth bombers as a supplement to its next-generation bomber fleets. This program is still in the early stages of development, with Air Force officials currently assessing which of the B-21’s systems should be migrated to the stealth drone and which can’t be due to cost limitations.

5) Mayhem: The highly secretive US Air Force effort to field a hypersonic stealth drone could finally bring the SR-72 to fruition

An SR-72 rendering. (Lockheed Martin)

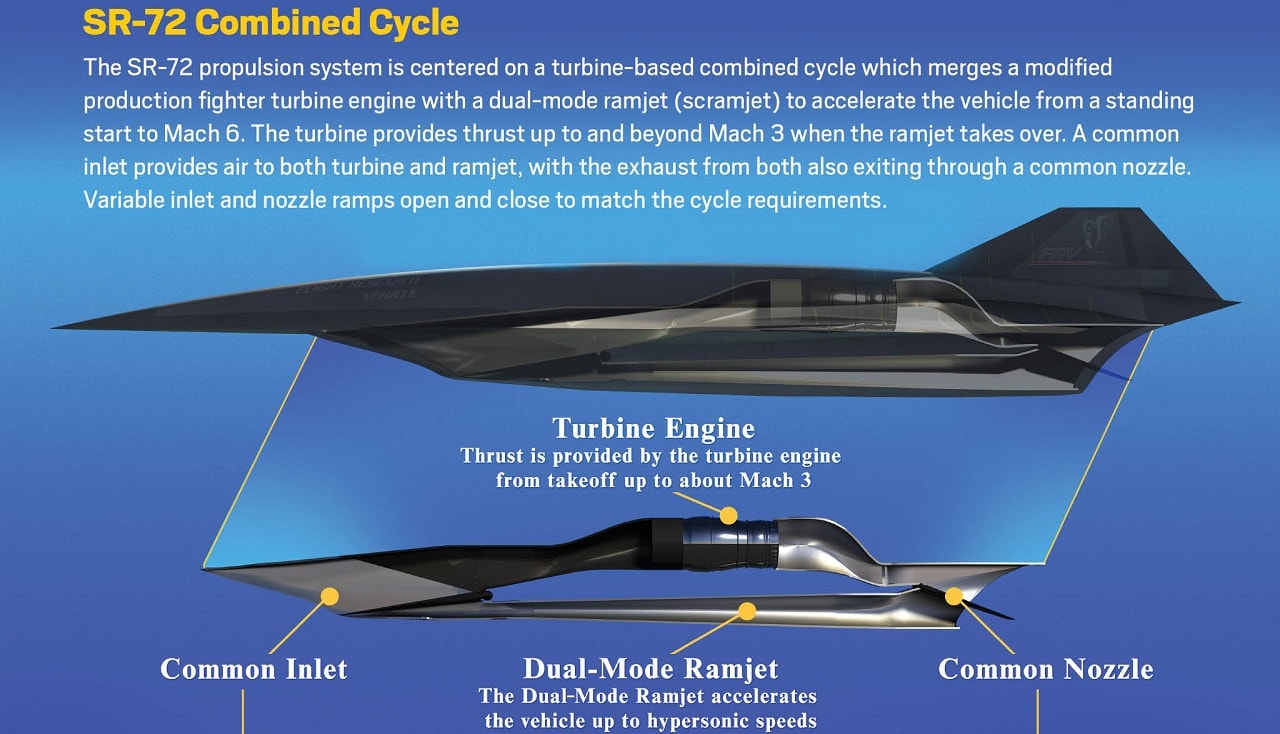

Hidden within the long list of hypersonic weapon programs drawing funds from Pentagon coffers, the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Mayhem Program appears to be developing a dual-cycle scramjet propulsion system for more than just missiles. The effort was originally tasked with fielding larger scramjet systems capable of propelling larger payloads further distances than unspecific “existing systems.”

Although Mayhem is regularly referred to as a missile program, a closer look at the branch’s issued Requests for Information (ROIs) suggests Mayhem is more likely aimed at fielding an uncrewed, reusable hypersonic drone platform capable of conducting two different specified mission sets: strike operations and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, or ISR, missions.

As Joseph Trevithick over at The War Zone noted late last year, Mayhem’s formal name recently changed from “Expendable Hypersonic Multi-Mission Air-Breathing Demonstrator” to “Hypersonic Multi-mission ISR and Strike,” and the effort has also been referenced as a “Multi-Mission Cruiser.” This strongly suggests that we’re not talking about a missile you fire at a target and forget about. The removal of the word “expendable” in conjunction with the “multi-mission” moniker both suggest Mayhem aims to field a reusable, autonomous platform that leverages what will likely be the world’s first dual-mode or turbine-based combined cycle (TBCC) hypersonic propulsion systems.

(Wikimedia Commons)

(Wikimedia Commons)In other words, Mayhem aims to field a turbine-based scramjet system that can function at all airspeeds from subsonic to supersonic and then hypersonic. Today’s ramjet and scramjet systems don’t function reliably until they’re moving at extremely high speeds, which are currently achieved using rockets that fire before the propulsion systems come online.

This concept is tantalizingly similar to the longstanding discussion about Lockheed Martin’s planned successor to the Mach 3.5-capable SR-71 Blackbird, known as the SR-72. All the way back in 2018, Lockheed Vice President Jack O’Banion seemed to indicate that an SR-72 demonstrator may have already flown, and he stated clearly that a full-sized propulsion system had already been built and tested. “The aircraft is also agile at hypersonic speeds,” O’Banion told a crowd at the 2018 SciTech Forum, “with reliable engine starts.”

A hypersonic strike and ISR platform would have far-reaching strategic ramifications: from the ability to deliver less-expensive non-hypersonic ordnance to targets at speeds above Mach 5 to rapid intelligence gathering even in places where satellite coverage is compromised. While the world worries about who is fielding new hypersonic missiles, it seems the Air Force is secretly planning to win the hypersonic aircraft race before the rest of the world even knows it’s begun.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in August 2022.

No comments:

Post a Comment