Willy Wo-Lap Lam

Executive Summary

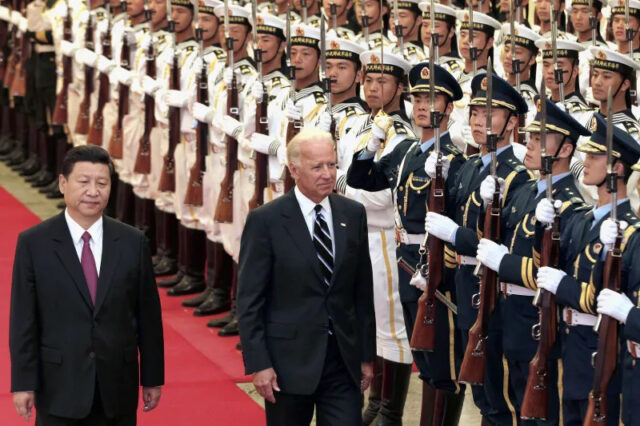

The increasingly ferocious competition between the United States and its allies on the one hand, and China and the “axis of autocratic states” on the other, has taken on unmistakable signs of a “new Cold War.” The leadership of President Xi Jinping, who is a hawkish nationalist convinced of the fact that “the East is rising and the West is declining,” is committed to challenging American dominance in fields ranging from economics and technology to geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific Area. President Joe Biden has crafted a so-called “anti-China containment policy” together with NATO in Europe as well Japan, South Korea and Australia in Asia. The Chinese response has been to continue supporting their long-time quasi-ally Russia and to build up a coalition consisting of non-democratic states in Central Asia together with Pakistan, Iran and North Korea so as to prevent the “eastern expansion” of NATO. Reports in the American media that several state-owned enterprises in China are helping Moscow with parts and components of military hardware has further inflamed the East-West contention over Ukraine. And given that flashpoints such as Beijing’s possible military action against Taiwan and the commitment of the U.S. and its allies to protect the “renegade island,” there is even a possibility of the “Cold War” turning hot.

The increasingly ferocious competition between the United States and its allies on the one hand, and China and the “axis of autocratic states” on the other, has taken on unmistakable signs of a “new Cold War.” The leadership of President Xi Jinping, who is a hawkish nationalist convinced of the fact that “the East is rising and the West is declining,” is committed to challenging American dominance in fields ranging from economics and technology to geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific Area. President Joe Biden has crafted a so-called “anti-China containment policy” together with NATO in Europe as well Japan, South Korea and Australia in Asia. The Chinese response has been to continue supporting their long-time quasi-ally Russia and to build up a coalition consisting of non-democratic states in Central Asia together with Pakistan, Iran and North Korea so as to prevent the “eastern expansion” of NATO. Reports in the American media that several state-owned enterprises in China are helping Moscow with parts and components of military hardware has further inflamed the East-West contention over Ukraine. And given that flashpoints such as Beijing’s possible military action against Taiwan and the commitment of the U.S. and its allies to protect the “renegade island,” there is even a possibility of the “Cold War” turning hot.After the “spy balloon” incident and evidence that several Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have supplied military components to the Vladimir Putin regime, relations between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States and its allies seem destined to go towards an irreversible downward spiral. The answer to the question of whether we are witnessing a Cold War or “new Cold War” analogous to the bitter struggle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union from World War II until 1991 has become more obvious. Developments in the foreseeable future seem to indicate that a new Cold War, although one that is substantially different in nature from the U.S.-USSR face-off, is in the offing.

This is despite denials from both Washington and Beijing that they are interested in fighting a Cold War. Both President Joe Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken have reiterated that Washington “is not looking for a Cold War” with China. Yet in a mid-2022 speech on Washington’s China policy, Blinken indicated that “China is the only country with both the intent to reshape the international order – and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do it.” [1] According to leading American political scientists Hal Brands and John Lewis Gaddis, “it is no longer debatable that the U.S. and China… are entering their own new Cold War. Chinese President Xi Jinping has declared it, and a rare bipartisan consensus in the U.S. Congress has accepted the challenge.” [2] Robert Daly and Rui Zhong of the Kissinger Institute have come to the same conclusion. “The United States and China are both struggling to frame their deteriorating relationship as something other than what it is: a Cold War,” they wrote. For example, they added, “the Biden administration denies that it wants to engage in a Cold War even as it prepares for one.” [3]

Senior Chinese cadres and official scholars have consistently claimed that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership does not think a Cold War with the U.S. is inevitable – and that Beijing is trying to avoid one. Without naming the U.S., President Xi, who is also CCP General Secretary and Commander-in-Chief, warned that “efforts to form cliques [of nations] and to foment a ‘new Cold War,’ ostracism and intimidation… will only push the world toward disintegration and even confrontation.” [4] Tao Wenzhao, an America expert at the official Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said Washington had made a big mistake in treating China as a Cold War antagonist. If the U.S. deems China as its biggest strategic competitor, he said, Washington “will continue escalating tensions, even turning that misjudgment into a self-fulfilling prophecy that would be no blessing – to China, the U.S. or the world.” [[5]] Another noted academic from Fudan University, Minghao Zhao, also highlighted Beijing’s aversion to a Cold War. “Both sides need to deal effectively with the transition to a relationship wherein the balance has tilted to a competitive angle and avoid the Thucydides trap,” he wrote, referring to the Athenian historian Thucydides’s characterization of the inevitable conflict between a status quo hegemon and a rising challenger. “Most Chinese analysts believe that China remains the underdog in this competition, as it lags considerably behind the U.S. in aggregate national strength.” [6]

The problem with Chinese interpretations of a new Cold War is that PRC leaders tend to use different characterizations depending on the occasion and the audience. While talking to foreign dignitaries, for example, during the Biden-Xi “mini-summit” on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Bali last November, the Chinese “leader for life” vowed that the PRC had no intention of challenging American supremacy. “This wide world can accommodate the developments of China and the U.S.,” Xi told Biden. “China never aspires to change the existing international order, to interfere in America’s internal affairs, or to challenge and replace the U.S.” [7] However, in internal meetings of CCP cadres, Xi has repeated a slogan first used by Mao Zedong in the 1950s, namely, “the East is rising and the West is declining.” At a recent Politburo meeting, Xi asserted that “modernization does not equal Westernization.” [8] On other occasions, the supreme leader expressed confidence that the “Chinese program and Chinese path” are so superior that it is only a matter of a decade or so before the PRC can claim superpower status – as well as being the final arbiter of events first in Asia and then the rest of the world. Recently, the People’s Daily came out with nine commentaries all entitled “Why the U.S. must fail.” Faults and shortcomings of Washington cited by the official paper included “disregarding rules; indulging in zero-sum games; moving against the [accepted] trends; refusing to compete [fairly]; claiming that only themselves are correct and applying double standards to others; lack of trust; failure to listen to other views and thinking that they alone are smart.” [9]

The series of “spy balloons” and other surveillance airships apparently sent by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) over the U.S. in the past few years has underscored the determination of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) administration to demonstrate their military and intelligence clout. Going back to the second five-year term of Xi’s predecessor, ex-president Hu Jintao had already departed from Great Architect of Reform Deng Xiaoping’s “keep a low profile” edict and started projecting both hard and soft power all over the world. Xi went further in his determination to overtake the U.S. in areas including the economy, technology, geopolitical clout in the Indo-Pacific Region as well as space exploration. It was Xi who laid out the specific time frame when China would displace the U.S. as the world’s sole superpower: from 2035 to 2049, when Beijing would mark the centenary of the Communist state’s foundation. [10]

Differences and Similarities with the Cold War

The four-and-a-half-decade geopolitical contest between the U.S. and the Soviet Union from the end of WWII to 1991 was an existential struggle between two antagonistic blocs. Until roughly the second half of the 1980s – when Solidary and the Catholic Church began winning battles in their struggle to end the Polish Communist Party’s stranglehold on power – the two blocs managed to co-exist largely because of the threat of mutual assured destruction. [11] The Soviet success in putting the first satellite in space in 1957 was followed by a series of dramatic scientific breakthroughs. The technological ingenuity of the well-educated class in the USSR even convinced many Americans that it would be hard to catch up with the Soviets. Apart from the Cuban crisis, however, leaders of the USSR did not have a well-articulated intention of becoming the arbiter of the universe through, for example, gobbling up countries within the broad Western alliance or cooperating with socialist regimes such as the CCP to bid for world supremacy. [ ]In fact, the Sino-Soviet rupture in 1960 – and Chairman Mao’s subsequent conviction that Beijing must form some kind of an alliance with the U.S. to counter the Soviet threat – largely prevented the USSR and the Warsaw Pact from harboring or executing any gargantuan, world-sized projects comparable to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that was launched by President Xi in 2013 [12] (see following story).

In the 1970s, Moscow did try to gain a foothold in the Middle East through supporting the Palestinians and Arab countries’ conflicts with Israel. However, while it gained influence in Iraq and Syria, the USSR was unable to prevent Saudi Arabia and Egypt’s diplomatic tilt towards the U.S. [13] Overall, the Kremlin could not match the overseas development funds and sophisticated weapons provided by the U.S. Then Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev’s decision in December 1979 to invade Afghanistan would lead to a military disaster and a depletion of both the assets and the legitimacy of the Communist regime. Afghanistan being a Muslim country, the Soviet misadventure also raised the ire of a number of countries and groups in the Middle East. [14]

Moreover, the Kremlin faced severe challenges both within the USSR and periodic pro-liberal, pro-democracy uprisings in Warsaw Pact countries such as Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary. Most importantly, the Soviet economy began to run into serious problems from the mid-1980s, which were manifested by long queues of citizens outside bakeries and supermarkets. In his remarkable book Will the USSR survive until 1984? dissident thinker Andrei Amalrik noted that Soviet authoritarianism had led to “the extreme isolation in which the regime has placed both society and itself.” “This isolation has not only separated the regime from society, and all sectors of society from each other, but also put the country in extreme isolation from the rest of the world,” he wrote. [15] The Kremlin had followed the strategy of focusing most of its resources on heavy industry and defense, at the expense of the standard of living of the population. By 1991, the Soviet GDP was less than half that of the U.S. Owing to the myriad problems within the CPSU, a group of young reformist leaders led by Mikhail Gorbachev began the internal dissolution first of the ideology and then the power structure of the party. Gorbachev’s concepts of glasnost and perestroika would undermine the orthodoxy of his dictatorial predecessors from Lenin through Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev, and Leonid Brezhnev. [16]

Misplaced Hopes

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the American historian Francis Fukuyama put forward the theory of “the end of history.” This was a reference to the fact that American-style values whose gist consists of general elections, the rule of law and laissez-faire economics have been proven to be mankind’s best model, particularly in light of the dismal failure of the Soviet socialist approach, which meant heavy control by the party of not only the market but everything else as well. [17] In the first few years after 1991, liberals represented by Vice-Premier Yegor Gaidar advocated for “shock therapy” to speed up quasi-capitalist liberalization of the economy. Unfortunately, experiments with market-oriented reforms ended up allowing the rise of oligarchs – and the collusion between the government and the plutocrats in monopolizing resources and ripping off ordinary folks. What makes possible the relative longevity of dictator Putin’s reign was his appeal to Russians’ sense of nationalism – and his efforts to restore the glory of Imperial Russia and the USSR. The high-sounding slogan “Make Russia Great Again,” however, would pave the way for Moscow’s current fiasco over Ukraine. [18]

The decisive victory of the U.S. over the Soviet Union resulted in the fact that for almost two decades, the global situation could accurately be characterized by former CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin as “one superpower, several great powers.” [19] By the middle of the 2000’s, however, it became apparent that American supremacy was again being challenged from another socialist country, CCP-ruled China. Anti-American fusillades came thick and fast particularly after pseduo-Maoist Xi Jinping came to power in 2012. In the eyes of Biden, Xi “does not have a single democratic bone in his body.” Blinken has repeatedly indicated that since “Beijing’s vision would move us away from the universal values that have sustained so much of the world’s progress,” Washington has “developed and implemented a comprehensive strategy” toward Beijing “to harness our national strengths and our unmatched network of allies and partners to realize the future that we seek.” [20] Other American allies have also raised the level of their concern about the “China threat” to unprecedentedly high levels. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said he supported a hardening of diplomatic relations with Beijing, since China posed a “systemic challenge to our values and interests.” And Canadian Foreign Minister Melanie Joly said in late 2022 that “China is an increasingly disruptive, global power [which] seeks to shape the global environment into one that is more permissive for interests and values that increasingly depart from ours.” [21]

A U.S.-China Cold War?

So are we witnessing a “new Cold War” or at least a quasi-Cold War that will soon metamorphose into a full-fledged one? There are two major differences between the U.S.-Soviet and U.S.-China contentions. The relations between the U.S. and the USSR were poisonously fraught right from WWII until 1991. Conversely, a kind of unlikely romance between the U.S. and the Middle Kingdom had developed until approximately the second half of the tenure of ex-president Hu Jintao (2007-2012). The “China Fantasy,” which underpinned a policy of engagement largely followed by presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, was that as the PRC became rich, its citizens would follow the rebellious students in Tiananmen Square and regard the Statue of Liberty as the icon of freedom and justice. [22] In time, members of the Chinese middle class would clamour for political participation and rule of law. Carter supported China’s “punishment” of Vietnam, which resulted in a bloody skirmish in 1979 between the erstwhile allies. Clinton, who got along very well with then-president Jiang Zemin (1926-2022), encouraged China to get into the World Trade Organization in 2001. It was a pivotal landmark for Deng’s open-door policy, and the leaps-and-bounds growth of China’s exports to the U.S. and the EU underpinned the Chinese economic miracle which lasted until the early 2010s. At the height of U.S.-China friendship, politicians and opinion leaders in America even talked about an inchoate “G2” – a reference to the fact that the U.S. would, together with a fast-liberalizing China, become joint-arbiters in global rule-setting. [23]

Unlike even than the most ambitious Soviet leaders, Xi, who is a super-nationalistic princeling (the offspring of the founders of the PRC), stated from the outset overarching goals for achieving the so-called Chinese dream, or the “great renaissance of the Chinese nation.” He also laid down the “two centenary goals.” By the year 2021, the centenary of the establishment of the CCP, China will eliminate poverty and all Chinese could become a part of xiaokangshehui, or a “moderately prosperous society.” And by 2049, the centenary of the founding of the PRC, China would overtake the U.S. and become the most powerful country on earth. [24] At the same time, Xi mapped out ambitious programs for the development of cutting-edge technologies such as semiconductors, supercomputers, AI, robotics, electronic vehicles, bio-engineering and pharmaceuticals. In the year 2015, the CCP leadership laid down a gameplan called “China 2025,” meaning that Chinese science and technology would play a leading role in the world in the not-too-distant future. [25]

Secondly, the PRC’s global influence is much more extensive than the Soviet Empire.

Preoccupied by issues both within itself and in Warsaw Pact countries, Moscow lacked the resources to extend its tentacles to other continents in a big way. The PRC, however, has the economic and technological resources to go after global influence. By 2010, China had emerged as the second largest economy – and the biggest trading nation – on earth. In 2022, China was the foremost trading partner of more than 120 countries and regions, including the ASEAN group of countries, Russia, Japan, Australia, South Africa and Brazil. The CCP administration has not been shy about weaponizing trade. Numerous countries have been penalized by Beijing after their leaders have met with the Dalai Lama, the head of the exiled Tibetan administration. Beijing boycotted Norwegian products for six years after a non-governmental committee awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2010. And after Seoul allowed the U.S. to install Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile batteries in South Korea in 2016, Chinese authorities put immense pressures on Korean firms operating in China – in addition to stopping tourists from visiting the country. [26]

The Xi administration has also spearheaded the formation of large, cross-continental trade and security blocs that testify to the PRC’s growing clout. China was the biggest proponent for the establishment of one of the largest trading blocs in the world, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which incorporates ASEAN members as well as Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. The RCEP was also perceived as a counterweight to the U.S.-centric Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which is a free trade pact among Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam. While the U.S. is not yet a member, it provided important geopolitical support to the grouping. [27] Previously, in the tail end of the Obama administration, Washington had taken the lead in forming a Trans-Pacific Partnership, one of whose goals was to “isolate” China; the TPP was abolished during the first month of the Trump presidency. Given the PRC’s ties with Russia and several near Eastern countries, Beijing has expanded the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to include not only China, Russia and the four Central Asian states, but also Pakistan, India, and Iran (starting early 2023). A host of non-democratic countries such as Afghanistan and Mongolia possess “observer status” while Belarus, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Armenia, Cambodia and Nepal have become “dialogue partners.” This potential “axis of autocratic states,” however, has internal problems such as the hidden rivalry between China and Russia, and the animosity between members such as Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, as well as India and Pakistan. Yet another trans-continental network at least partially initiated by the Chinese and Russians is the BRICS bloc. Apart from Brazil, India and South Africa, Beijing and Moscow have also expressed an interest in recruiting members including Algeria, Argentina, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt and Afghanistan. BRICS has so far opposed sanctions levied by the UN on rogue countries such Iran, North Korea and Myanmar. [28]

Yet a truly overarching endeavor of the Xi leadership is the Belt and Road initiative, which would help nations across five continents build infrastructural projects such as ports, airports, super-highways and high-speed railways, many of which will link China up with Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Europe and Africa. This series of projects would involve mainly Chinese government financing: the initial estimate is a budget of $1 trillion for the first five years. This would be seven times the amount that the U.S. spent on the Marshall Plan for resuscitating war-torn Europe in the 1940s and 1950s. The BRI is closely enmeshed with Chinese efforts to acquire key ports and other facilities ranging from Hambantoto in Sri Lanka and Gwadar in Pakistan to the Piraeus in Greece and a quasi-military base in Djibouti. Huawei and other IT state-owned enterprises are actively laying down 5G-related broadband lines for a number of less developed countries in Central Asia, Africa and Latin America. That this infrastructure spending binge is related to hard-power projection is without doubt. Despite a pledge made in an earlier era that the PLA would not construct overseas military bases, such facilities have been set up in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Djibouti, among other strategic spots. [29]

At the same time, China would project its soft power through a program called dawaixuan or “world-wide propaganda and united front work” aimed at the promulgation of Chinese soft power through generous grants to universities and think-tanks around the world as well as contributions to the campaign funds of politicians from Australia to the U.S. At least according to intelligence organizations in the U.S., Canada, U.K., and Australia, Chinese spies – to include diplomats, journalists, businesspeople, scientists and even graduate students working in rich countries – would conduct different forms of espionage geared toward stealing know-how from the most advanced universities and industrial laboratories. Influence peddlers with deep pockets are also pumping cash into the election campaigns of both ruling and opposition parties in Western countries. Australia went so far as to expel a Chinese-Australian businessman who was deeply involved in allegedly bribing politicians in that country. In late February, The Globe and Mail broke the story of an extensive campaign by the Chinese to influence the Canadian federal elections in 2022. [30]

The peculiar nature of this “new Cold War” has been based on the interpenetration between China, on the one hand, and the U.S. and its allies on the other. Despite the pandemic, 290,000 Chinese students went to the U.S. for further studies in the 2021-2022 term. Hundreds of thousands of professionally proficient Chinese – most of whom having acquired U.S. citizenship or green cards – are working in America’s top tech enterprises. Beijing has an extensive network of intelligence gatherers and influence peddlers who report to different mainland departments as well as the seven official Chinese missions in the U.S. In 2020, President Trump closed down the Houston Chinese Consulate on the grounds that it was a command center for spying and intellectual property (IP) theft. [31]

Conclusion

At the height of the old Cold War, interactions between the U.S. and the USSR was largely restricted to diplomatic and military dealings. From the moment in the early 1910s when the U.S. government used the indemnities from the Qing dynasty court to set up Tsinghua University – which is China’s most prestigious science and engineering school – American professors, in tandem with missionaries, began coming to China in huge numbers. The relationship becomes even more entrenched and multifaceted after China’s accession to the WTO. Multi-dimensional interaction and cooperation in the field not only of trade and technology transfer but also overall human interactions simply exploded. During the “fantasy period” involving the “G2” idea, Sino-American relationship was so intimate that the Chinese phrase nizhongyouwo wozhongyouni [“you are part of me and I am part of you”] was used to describe the close ties characterized as “Chimerica.” [32]

But bilateral ties underwent a sea change when it became obvious that “ruler for life” Xi is determined to displace the U.S. as the status quo superpower. Despite the economic contretemps bedevilling the PRC, the CCP administration still has the means to fiercely compete with the U.S. on multiple fronts, particularly in the geopolitical arenas of East Asia and Southeast Asia, Central Asia (including Russia, which is becoming a junior partner in the Sino-Russian quasi-alliance) and Africa. The various measures taken by the Biden administration to rein in China’s high-tech sectors have been relatively successful. Partly in view of the recent agreement among the U.S., Japan and the Netherlands about choking off the chip-related supply chain to the PRC, different industries in China have been dealt a big blow. [33] Moreover, Washington has woven together a spider-web of alliances with the aim of containing China, particularly when the Xi administration has chosen to tie itself to the Russian chariot. These alliances include the U.S.-NATO agreement to jointly handle the challenge of the China- and Russian-led “axis of autocratic states;” America’s AUKUS agreement with the U.K. and Australia; the Quad (the U.S., Japan, India and Australia); the long-standing Five Eyes Alliance among the U.S., the U.K., Canada, Australia, New Zealand; and much-enhanced defense ties between the U.S. on the one hand, and Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and the Philippines on the other. [34]

Equally crucial is the fact that despite the U.S.-USSR animosity, the probability of a hot war began to dissipate following the seismic changes that began in Poland in the early 1980s. Taiwan is a unique problem that has few parallels in the contention between the U.S. and other large powers. Various experts in America and China have painted a pessimistic picture of the PLA seeking to annex Taiwan by the mid-2030s at the latest. Despite the fact that Washington is unlikely to put “boots on the ground” in Taiwan, it has transferred sophisticated hardware to the Taiwanese army. Since his inauguration, Biden has on at least three public occasions declared that Washington would come to Taiwan’s aid in case of a PLA invasion. [[35]] Japan, which appears to believe that the chances are high that it will have to engage the PLA in the immediate aftermath of the latter’s actions against the “Taiwanese separatists”, has not only expanded its military budget but signed significant mutual-defense agreements with Australia and the U.K. While it is improbable that the PLA’s firepower will exceed that of the U.S. – especially the combined military strength of the U.S. and its European and Asian allies – there are worries that Xi might still want to reunify Taiwan in his lifetime. Given the growing socio-economic problems in the PRC, the possibility also exists that the Xi leadership might seek a foreign adventure to divert dissatisfaction at home. [36] There are widespread fears that the cat-and-mouse games frequently played by American and Chinese jetfighter pilots close to Taiwan and South China Sea hotspots could lead to accidental skirmishes that would spiral out of control, in the process setting into motion a “hot war.” [37] By contrast, in the “proxy war” with Russia over Ukraine, the U.S.-led Western Alliance is much more cautious about sending advanced weapons such as jetfighters to the war-torn country.

In his 2022 book The Avoidable War, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said it was possible to manage the deteriorating strategic competition between the two behemoths. He proposed that “some basic guardrails [be] put in place, with the agreement of both sides, to prevent the relationship from spinning out of control by accident, rather than by design.” Rudd admitted however, that this is a tall order given that “the stock of political and diplomatic capital available in the bilateral relationship has been depleted to near zero.” [38] Russia’s humiliating experience in Ukraine might persuade Xi and the Chinese leadership, including the PLA top brass, to think twice before initiating hostilities against Taiwan. Moreover, the Chinese economy, which is buffeted by outsize debts, weak consumer spending, the greying of the population, and the relocation of foreign factories away from the Chinese coast to Southeast Asia, is unlikely to return to the high-growth decades of the 1990s and 2000s. [39] There is, however, the counter-argument that Xi, who is obsessed with accomplishing an epochal national goal that even eluded his idol Mao Zedong, might be persuaded to take a gamble on Taiwan before the gap between China’s economic and military capacity and those of the U.S. and its allies were to significantly widen. Sinologists Hal Brands and Michael Beckley have argued that a China in decline “makes it more dangerous, not less.” For example, the two experts said, China could soon try to seize Taiwan, while it is still able to do so. [40] Given such dire scenarios, the possibility is growing that the establishment of mutually acceptable and sustainable “guardrails” for bilateral ties requires a level of perspicacity and flexibility that is beyond the current leaderships of both countries.

No comments:

Post a Comment