Martin Kleiven Jørgensen

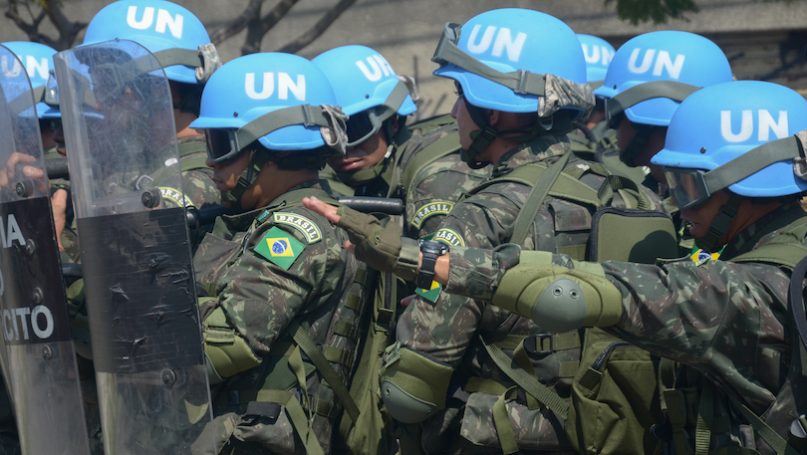

The turn towards more robust peacekeeping came as a response to failures of United Nations (UN) peacekeepers in the 1990s to hinder mass atrocities, such as in Rwanda and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Tardy, 2011). Today, there is a consensus that the UN was too slow to respond and that the peacekeepers on the ground were risk-averse and lacked the necessary equipment and personnel to prevent these atrocities (Rhoads, 2019). The UN’s Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) (2009, p.21) defines robust peacekeeping as “a political and operational strategy to signal the intention of a UN mission to implement its mandate and to deter threats to an existing peace process in the face of resistance from spoilers”. A robust approach seeks to have a more powerful and proactive military to protect civilians (Hultman, 2010) and authorises peacekeepers to use force on the tactical level in self-defence and defence of the mandate (e.g., protecting civilians) against certain armed factions (DPKO, 2009).

However, practitioners disagree on whether the robust turn has led to more effective peacekeeping (Laurence, 2019). Drawing on Hunt’s (2017) argument, this essay argues that the turn towards robust peacekeeping has had several unintended consequences, with the potential of undermining the unity of effort and effectiveness of UN peace operations. The essay begins by exploring how risk-averse troops often hinder effective implementation of the Protection of Civilians (POC) mandate and how robust peacekeeping missions might be effective in the short term. It proceeds by investigating how these missions clash with traditional principles of peacekeeping and can have unintended implications for humanitarian access, the security of UN personnel and civilians and the behaviour of Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs). It continues by examining how robust peacekeepers can undermine a peace process by using force. Lastly, it investigates how the ambiguity of robust peacekeeping can affect the unity of effort of UN peace operations.

Risk-averse troops can prevent effective implementation of the POC mandate, and peacekeepers must use force if there are no other alternatives to protect civilians from imminent threats. Advocates for robust peacekeeping rightly argue that a lack of use of force protection and passivity among peacekeepers have often prevented more effective implementation of the POC mandate (Rhoads, 2019). For instance, in Juba in South Sudan, in July 2016, Government and Opposition forces fired weapons indiscriminately, striking protection of civilian sites and UN facilities, causing the death of 20 civilians and injuring more (United Nations, 2016). The UN report also notes that Government forces attacked Terrain Camp (a private UN compound) and were responsible for sexual abuse, robbery and murders of UN personnel, local staff, and aid workers. Still, UN peacekeepers did little to prevent these atrocities despite receiving reports, in some cases witnessing these incidents, and that the headquarters of the UN Mission in South Sudan was a kilometre away (United Nations, 2016). The report concludes that the peacekeepers did not intervene effectively due to a risk-averse attitude and lack of unified command, illustrating the limitations of risk-averse troops. But there is a distinction between defensively using force to protect civilians, as the peacekeepers should have done in Juba, and carrying out offensive operations against insurgents.

Using peacekeepers to carry out offensive operations might be effective in the short term to protect civilians but clashes with traditional core principles of peacekeeping. According to the High-level Independent Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (HIPPO) (2015), peacekeepers must use all tools available to protect civilians. Where there is no peace to keep, using force could be effective in the short term (Hunt, 2017) as providing military support to governments in civil wars could increase the likelihood of ending the fighting (Hultman, 2010). As such, robust peacekeeping can stabilise conflicts (increase the government’s legitimacy by protecting the civilian population through reducing and preventing violence) (Aoi et al., 2017). For instance, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the UN deployed the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) to defeat the M23 group as the latter had indiscriminately targeted civilians (Laurence, 2019). Though the FIB defeated the M23, it is difficult to imagine how it could adhere to the traditional principle of peacekeeping of minimum use of force in defence of the POC mandate whilst fulfilling its mandate to neutralise insurgents (Hunt, 2017). However, the FIB may not have used more force than necessary to defeat the M23 and thus saved civilians. It is difficult to establish whether the latter is true, but the use of FIB contradicts with the core principle of impartiality (Moe, 2021).

The robust turn has, in practice, led to the UN becoming a direct party to different conflicts, and undermining its impartiality. Robust peacekeeping missions (e.g., in Mali and the DRC) support the government against non-state actors and thus lose their impartiality (Hultman, 2010). In theory, UN peacekeepers should implement their mandates impartially (Willmot et al., 2015), meaning they should hold both government and non-state forces responsible for human atrocities. Still, in practice, this is often not the case. For instance, in DRC, UN peacekeepers have not held government forces, at least not to the same extent as rebel forces, accountable for human rights violations, harming their reputation and legitimacy (Willmot and Sheeran, 2013). As the UN supports the government, it is more difficult for the organisation to distance itself from these actions. But as Willmot and Sheeran emphasise, human rights monitoring of or use of force against government forces could lead to a less cooperative government (e.g., withdrawal of consent for the mission, restrictions on humanitarian access, etc.), making it harder for the UN to protect civilians. Despite this, the UN must strive to hold all actors accountable for human rights violations and equivalent as the loss of impartiality can have negative implications for the security of UN personnel and civilians and humanitarian access.

A loss of impartiality can lead to attacks on peacekeepers and prevent them from fulfilling their duty to protect civilians. Ensuring the protection of UN personnel is vital for the efficacy of mandate execution (Willmot et al., 2015), referring to that one must protect UN personnel (e.g., humanitarian workers) to ensure that they can implement their mandates. However, there is always a risk of attacks on UN personnel in peacekeeping missions, especially when the UN is considered a party to the conflict (Sherman, 2018). When peacekeepers lose their impartiality, they also lose their immunity granted under international law and might instead be deemed as legitimate targets in conflicts (Willmot et al., 2015). Willmot et al. note that this might lead to heightened risks for UN personnel when they thwart the objectives of insurgents. This is evident in northern Mail, where non-state actors consider the UN as a legitimate target as the latter supports the “enemy” (the government) (Moe, 2021). Though it is difficult to attribute the frequency of attacks on peacekeepers to the extent a peace operation is robust (Hunt, 2017), peacekeepers might be deemed legitimate targets if they lose their impartiality, undermining the effectiveness of peacekeeping. A loss of impartiality can also have negative implications for humanitarian access.

When UN peacekeepers lose their impartiality, it can harm the ability of humanitarian actors to access those in need. All humanitarian organisations must adhere to four principles:

they must not get involved or take sides in conflicts (Neutrality), they must be independent of any political, economic or military objective (Independence), they must address suffering wherever it is found (Humanity) and should only be guided by the need of the people, without any discrimination (Impartiality).(Hess, 2019, p.30).

As humanitarian organisations depend on negotiating access with the authorities or belligerents in control of different areas (Visser, 2019), following these principles are vital to gain humanitarian access. But, for UN agencies and humanitarian actors reporting to the UN, it is often difficult to distinguish themselves from the political objectives of the UN (Metcalfe et al., 2011). In turn, when the UN loses its impartiality, the perception of humanitarian actors and their ability to deliver aid is also often affected. For instance, in Yemen, the Houthis have obstructed the delivery of humanitarian aid as they consider the UN and its agencies to be partial and support their enemy, the Hadi government (Coppi, 2018). Hence, when belligerents perceive UN peacekeepers to be partial, it can affect the ability of humanitarian actors to deliver aid, undermining the goal of peacekeeping to protect civilians.

Civilians, which peacekeepers are mandated to protect, may also be targeted due to a loss of impartiality of peacekeeping missions. There is a risk of collateral damage to civilians due to robust military operations attempting to neutralise insurgents (Tardy, 2011). Although such collateral damage is rare (Hunt, 2017), these attacks might lead to retaliation from insurgents. For instance, in Mali, the loss of impartiality of the UN mission resulted in non-state actors opposing the government deemed all contributors to the UN mission, including civilians, as legitimate targets (Moe, 2021). Similar events occurred in DRC, where insurgents have attacked villagers considered traitors for cooperating with the UN (Oxfam, 2015). Even when insurgents respond with force to robust military operations but do not target civilians specifically, it can lead to an increased risk of collateral damage to civilians. Hence, robust peacekeeping missions can lead to attacks on those the missions are mandated to protect.

When peacekeepers fail to protect civilians, it can harm the perception of peacekeeping as an effective tool as “there is an expectation that peace operations should improve the security and well-being of those affected by conflict” (Peter, 2019, p.5). In turn, this might affect the willingness of TCCs to contribute troops to UN peace operations.

The perception of peacekeeping as an effective tool and the security concerns to UN personnel and civilians attributed to robust peacekeeping might affect the willingness of TCCs to contribute troops. Some of the largest TCCs like Bangladesh and Ethiopia have raised concerns about the more ambitious and risky mandates the UN Security Council authorises (Rhoads, 2019). TCCs have a great interest in ensuring the safe return of their forces from UN peace operations (Willmot et al., 2015). It might be difficult for a government to explain to its population the deaths of its soldiers when there are no apparent gains of involvement in a conflict (e.g., political or economic benefits). Furthermore, member states of the Global South have been concerned with whether robust peacekeeping might lead to a more activist and intrusive UN in the internal affairs of states (Tardy, 2011). TCCs could be more reluctant to contribute troops to the UN if they lose confidence in peacekeeping as a tool (Hunt, 2017). As the UN does not have an army and is dependent on its member states to provide resources and personnel (Coleman and Williams, 2021), a greater reluctance amongst the TCCs to contribute troops could undermine the effectiveness of UN peacekeeping. Still, it is uncertain to what degree these concerns will affect the willingness of TCCs to contribute troops. There is, therefore, a need to further assess the extent to which the robust turn affects perceptions of peacekeeping as a tool, particularly as the use of force can undermine a peace process.

Robust peacekeeping can, in certain cases, undermine a peace process. Creating peace requires political solutions, and a greater military capability will not solve the root causes of violence (e.g., social inequalities or political marginalisation) (HIPPO, 2015). A key task of peacekeepers is to help implement peace agreements (Peter, 2019). But when peacekeepers “start killing people and become a party to conflicts they are supposed to control, they become a part of the problem” (Willmot and Sheeran, 2013, p.536). In DRC, the government admitted that the ineffectiveness of state institutions, (e.g., its inability to address poverty and social inequalities) was a root cause of the conflict (Tull, 2018). As Tull notes, the government, therefore, agreed to substantial reforms (e.g., democratisation and security reforms) to address this. However, when the FIB defeated the M23, one of the government’s biggest enemies, it changed the balance of power in favour of the government, disincentivising the latter from implementing these reforms as it would no longer benefit them (Tull, 2018). By consolidating the power of the government, it constrained the ability of other non-violent political actors to represent and raise their concerns (Hunt, 2017), affecting the inclusiveness of the peace process in the DRC. Though robust peacekeeping has not been the only challenge to the peace efforts in DRC, the example illustrates that robust peacekeeping can undermine peace efforts. Another explanation for this is the ambiguity of robust peacekeeping.

The lack of consensus on what robust peacekeeping means in practice can affect the unity of effort in peacekeeping operations. Robust peacekeeping is difficult to operationalise since it is ambiguous and ill-defined (Tardy, 2010). One needs to clarify what aspects of a mandate (e.g., human rights monitoring, disarming combatants, etc.) might require the use of force (HIPPO, 2015) and, if so, in what fashion. Furthermore, the distinction between peacekeeping and peace enforcement has, in practice, become blurred. On paper, peace enforcement allows the use of offensive force on the strategic level and does not require consent from the host authorities (Tardy, 2010). Peacekeeping, however, needs consent from the host state and should only use force on the tactical level in a defensive fashion (DPKO, 2009). Still, robust peacekeeping missions in Mali and DRC have received consent from the host governments to carry out strategic offensive operations against insurgent groups (Moe, 2021). Hence, leading to confusion about the distinction between robust peacekeeping and peace enforcement (Tardy, 2011). Such confusion can lead to different understandings and expectations of what robust peacekeeping means in practice, affecting the unity of effort of peace operations. Without a shared understanding of the term, it risks undermining the effectiveness of peacekeeping.

To conclude, the essay argues that the move towards more robust peacekeeping has had unintended consequences which can undermine the unity of effort and effectiveness of peacekeeping. Risk-averse troops often prevent effective implementation of the POC mandate, and peacekeepers must use force if there are no other alternatives to protect civilians from imminent threats. Still, there is a distinction between using force defensively and offensively. Using peacekeepers to carry out offensive operations against insurgents might be effective in the short term but is often problematic in the long term and clashes with traditional core principles of peacekeeping (e.g., limited use of force and impartiality). The loss of impartiality is problematic when the government the UN mission supports is responsible for human rights violations and often has implications for humanitarian access, the security of UN personnel and civilians and the behaviour of TCCs. However, it is uncertain to what extent the robust turn will affect humanitarian access, the security of UN personnel and civilians and the behaviour of TCCs in the future. But there is a need to clarify what robust peacekeeping means in practice as its current lack of clarity risks undermining the unity of effort of peacekeeping operations.

No comments:

Post a Comment