Jan Joel Andersson

INTRODUCTION

European defence is built on cooperation: between NATO and the EU; between the EU and its partners; and a myriad of multilateral and bilateral defence cooperation agreements among EU Member States and beyond. But is this intricate architecture a confusing mishmash of duplications and inefficiencies, or a web of steel providing the foundation for stronger European defence?

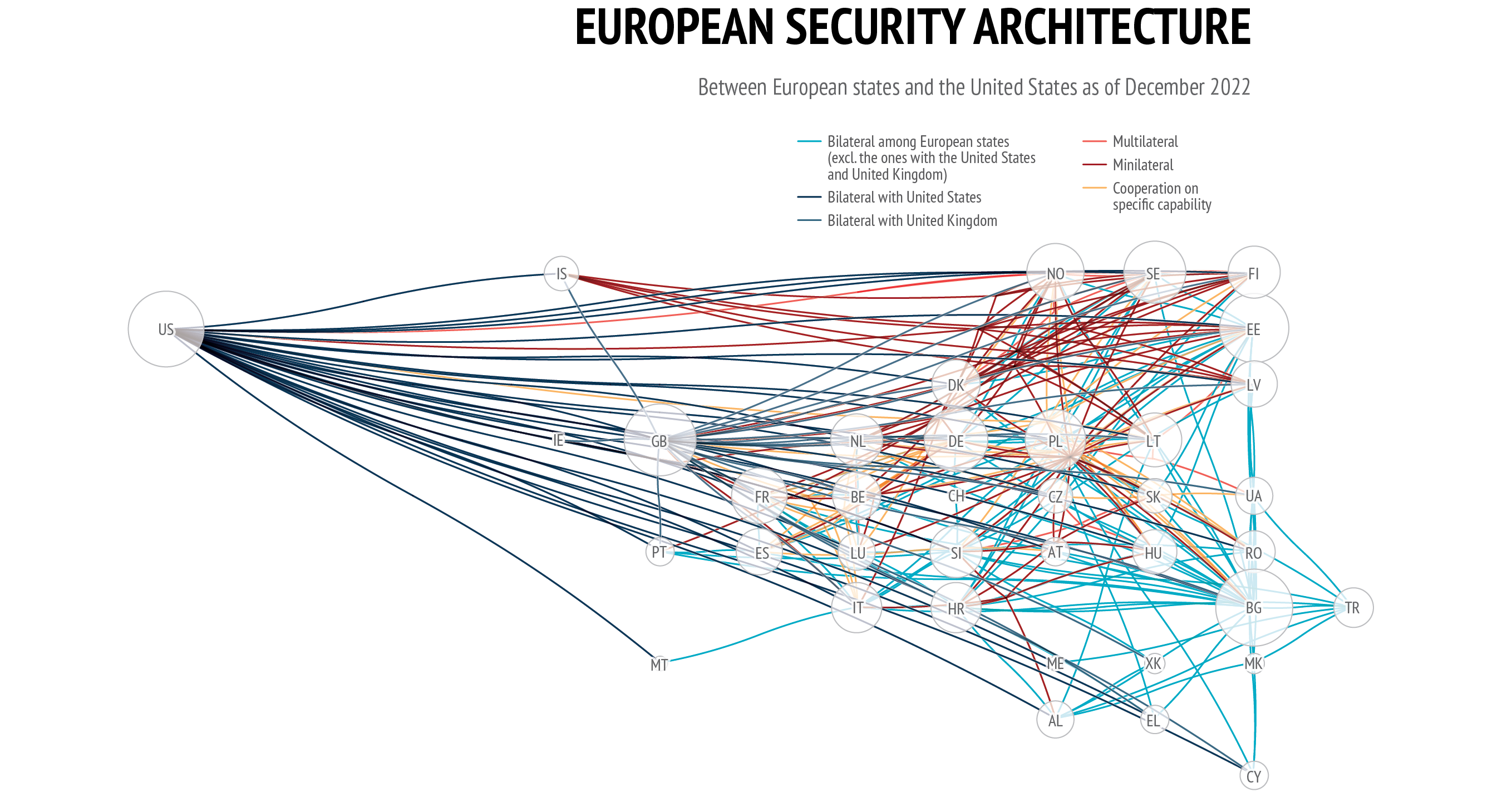

European defence is built on cooperation: between NATO and the EU; between the EU and its partners; and a myriad of multilateral and bilateral defence cooperation agreements among EU Member States and beyond. But is this intricate architecture a confusing mishmash of duplications and inefficiencies, or a web of steel providing the foundation for stronger European defence?In Europe, the EU’s most important defence partner is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). With 21 – soon 23 – EU Member States also being NATO Allies, the two organisations are the key pillars of the European security architecture (1). This architecture, however, also relies on the EU’s partnerships with key countries outside the Union as well as on EU Member States’ own multilateral and bilateral defence cooperation arrangements.

Accordingly, this Brief is structured in two parts. The first part analyses some of the EU’s most strategic partnerships and suggests ways in which these could be further tailored and enhanced, for instance, through a so-called ‘Strategic Partnership Plus’ format. The second part shifts the focus to EU Member States’ various multilateral and bilateral defence cooperation arrangements, introducing the analytical concept of ‘institutional nesting’ to reduce overlap and ‘meeting fatigue’, while increasing efficiency, coherence and output. The Brief concludes with reflections on how to ensure that European defence partnerships lay the foundations of a stronger Europe.

TAILORING EU DEFENCE PARTNERSHIPS

In the Strategic Compass, the EU commits to ‘engage more coherently, consistently and comprehensively’ with its bilateral partners and thus build ‘tailored partnerships’ based on shared values and interests (2). Given the grave security situation in Europe following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, strengthening defence cooperation is a priority for the EU and its Member States.

NATO

For most countries in Europe, the primary security organisation is NATO. In response to Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, NATO enhanced its defence planning and began the forward deployment of troops in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (3). Reacting to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, NATO significantly reinforced its troop presence in those four countries and also established four new multinational battlegroups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia. In June 2022, NATO endorsed a new Strategic Concept, reaffirming the core tasks of deterrence and collective defence, and invited Finland and Sweden to join the alliance (4).

The Strategic Compass reiterates the EU’s commitment to further strengthening the bond with NATO in accordance with the Joint Declarations from 2016 and 2018, and most recently, January 2023. While maintaining decision-making autonomy of both organisations, cooperation – based on inclusiveness, reciprocity, openness and transparency - on 74 identified actions has been steadily progressing (5). Since 24 February 2023, EU-NATO cooperation has intensified; in fact, it has never been closer (6). Emphasising the importance of this partnership, both the EU’s Strategic Compass and NATO’s new Strategic Concept call for further enhancing cooperation in areas of mutual interest, including military mobility, hybrid, cyber and climate change-related threats, outer space, and emerging and disruptive technologies.

While EU-NATO cooperation is now ‘the established norm and daily practice’ (7), the partnership remains subject to a number of constraints. Despite now much stronger support from Washington, some parts of NATO continue to view the EU’s burgeoning role in defence with scepticism. Indeed, while the highly anticipated (and repeatedly delayed) third Joint Declaration speaks of bringing the partnership ‘to the next level’, it is difficult to understand what this next level is and how to reach it (8). Due to the unresolved conflict between EU Member State Cyprus and NATO ally Turkey, the existing legal framework between EU and NATO can neither be reviewed nor updated. A higher level of defence cooperation is difficult to achieve without a formal agreement on how to share classified information. Also, other concerns such as restrictions on third states’ participation in the EU’s Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), projects funded by the European Defence Fund (EDF), and the compatibility between the NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP) and the EU’s Capability Development Plan (CDP) remain sources of contention. They are reflected in the new Joint Declaration’s call for transparency and the fullest possible involvement of non-EU NATO Allies in the EU’s defence initiatives, and vice versa (9).

Accordingly, further strengthening the EU-NATO partnership may not require more declarations but more coordination of policies and complementarity in existing cooperation. The fact that the EU finances weapon deliveries through the European Peace Facility (EPF) and trains Ukrainian soldiers in the EU Military Assistance Mission Ukraine (EUMAM), while NATO provides defence and deterrence for its Allies and supports EU Member States bordering Russia, is already a good example. Another example is the so-called Parallel and Coordinated Exercises (PACE) that could be further enhanced and expanded, even if joint and integrated exercises would ideally be a much more efficient way of proceeding.

Ultimately, developing coherent, complementary and interoperable defence capabilities is key for both organisations. However, bringing cooperation to the ‘next level’ will require EU Member States and NATO Allies to better define in which organisation they wish to undertake what actions. Here, defence innovation is an example. The EU Member States have established a Hub for European Defence Innovation (HEDI) in the European Defence Agency (EDA), but many of the same Member States are as Allies also setting up a Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) in NATO. HEDI and DIANA will both be working with public and private sector partners, academia and civil society to develop new defence-related technologies. To avoid duplication, cross-briefings between EDA and NATO have taken place, but to ensure long-term complementarity further coordination will have to be established. Other areas mentioned in the new Joint Declaration where clear guidance from capitals will be necessary to ensure complementarity are geostrategic challenges, protection of critical infrastructure, outer space, climate change and security, as well as foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI).

THE UNITED STATES

The transatlantic relationship with the United States was called ‘irreplaceable’ in the 2003 European Security Strategy and remains so today. A strong momentum on defence cooperation was created by the 2021 EU-US Summit and the subsequent establishment of a dedicated dialogue on security and defence, and the 2022 Strategic Compass lists the United States first among the EU’s bilateral partnerships (10).

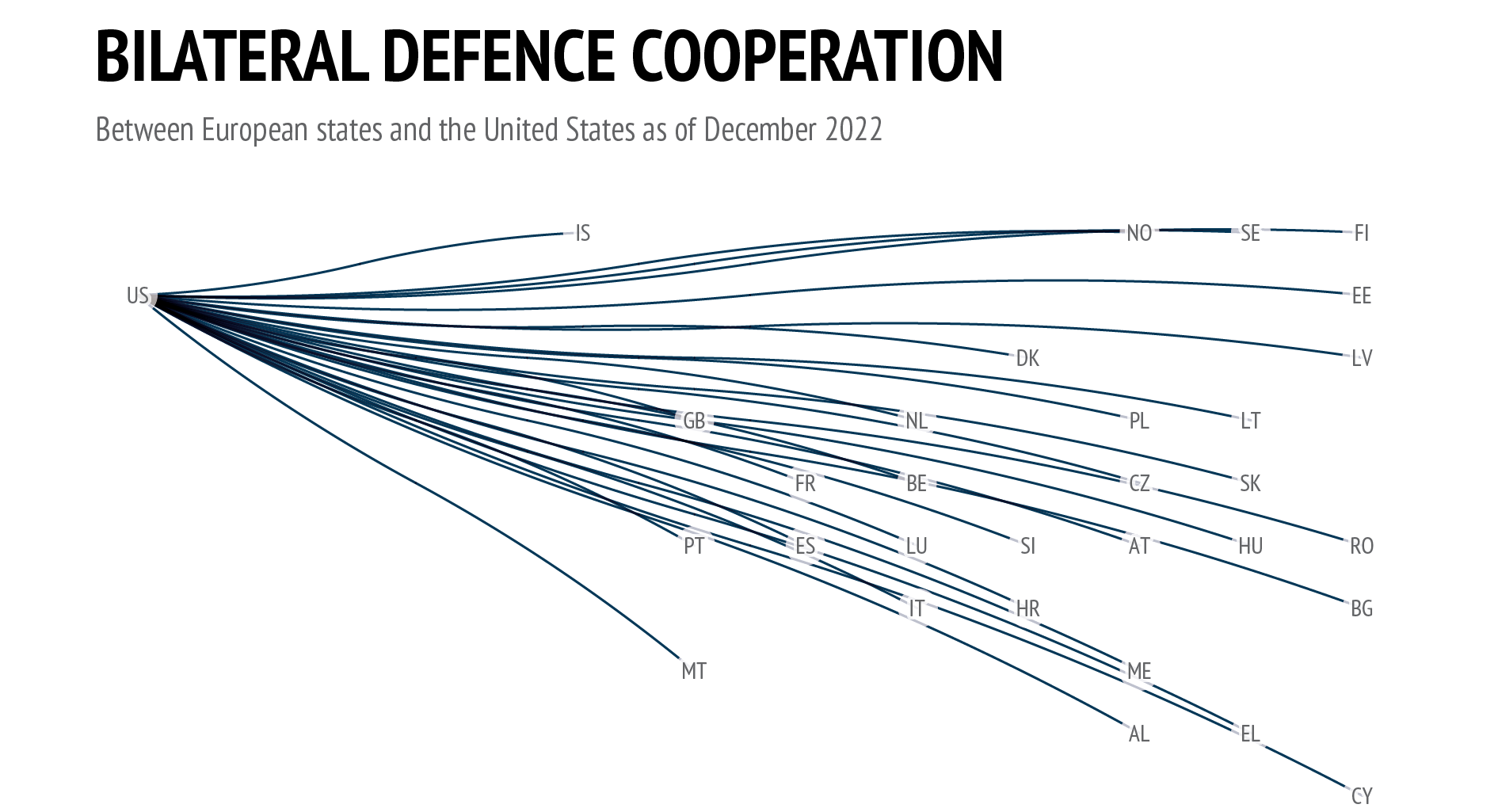

The EU’s growing role in defence offers more opportunities for engaging the United States, as demonstrated by both the invitation to the US to join the PESCO Military Mobility project in 2021 and the strong coordination on weapons deliveries to Ukraine and sanctions (11). The conclusion of an Administrative Arrangement between the EDA and the US Department of Defense in 2023 provides a framework to explore further opportunities, even if capability development and research & technology (R&T) activities remain outside the initial scope of cooperation (12). However, as States have their own bilateral security and defence partnership agreements with the United States. It is therefore critically important to identify the areas where Member States see a common need to discuss defence with the United States at the EU level. Here, protecting the global commons, and securing maritime routes, space assets and seabed infrastructure like undersea communication cables and energy pipelines could provide new areas for such EU-US security cooperation.

NORWAY

The Strategic Compass describes Norway as the EU’s ‘most closely associated partner’ due to its membership of the European Economic Area (EEA), which allows Norwegian industry to participate in the EDF, but also by virtue of Norway’s long-standing Administrative Arrangement with the EDA since 2006. Through seconded staff and participation in research and capability development projects, Norway is very actively engaged in the EDA. Under a Framework Participation Agreement (FPA), Norway has contributed civilian experts, military staff and naval assets to 12 EU CSDP missions and operations; it also contributed troops to the EU Nordic Battlegroup in 2008, 2011 and 2015 (13).

Norway has a comprehensive defence dialogue with the Union since 2021. That same year, it was invited to join the EU PESCO project on Military Mobility. In 2022, Norway became the first third country to contribute to the EPF in support of EUMAM (14). In addition, Norway cooperates with EU Member States in other defence formats such as the Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO), the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), the Northern Group, and the European Intervention Initiative (EI2) as well as in many bilateral defence constellations.

In sum, Norway’s security and defence cooperation with the EU is very close already. Any further deepening of this partnership could include invitations to Oslo to participate in more PESCO projects. Provided that Norway would be willing to commit to a further alignment with the EU’s level of ambition in capability development, it could also be invited to contribute to future revisions of the CDP and the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD).

CANADA

Canada is a long-standing partner of the EU in security and defence. Based on a Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) signed in 2016, strategic dialogues on cybersecurity, development and counter-terrorism have been conducted. The first meeting of the EU– Canada Joint Ministerial Committee in December 2017 identified deeper security and defence cooperation as one of three top priorities (15). Like Norway, Canada has contributed troops to CSDP missions and operations and in 2021, Canada was invited to join the EU PESCO project on Military Mobility (16).

Shared commitment to the European security order is a key reason for developing a closer EU-Canada defence partnership. Given Canada’s long-term engagement in European security, a tailored partnership could include further cooperation on the development of coherent and interoperable capabilities. Especially for operations in the Arctic, joint capability development of icebreakers, offshore patrol vessels, and surveillance and sensor systems for the polar region could be considered. Better protecting seabed infrastructure like communication cables and energy pipelines across the Arctic would provide another area for enhanced cooperation. In order to realise such aspirations, an Administrative Arrangement between the EDA and Canada could be advisable.

THE UNITED KINGDOM

Formal foreign and defence policy cooperation is not part of the EU-UK Agreement reached at the end of December 2020 (17). Foreign policy and defence were left out of negotiations at the request of the UK. Consequently, the Strategic Compass simply states that the Union remains ‘open to a broad and ambitious security and defence engagement with the United Kingdom’.

The lack of closer EU-UK defence cooperation is becoming increasingly awkward.

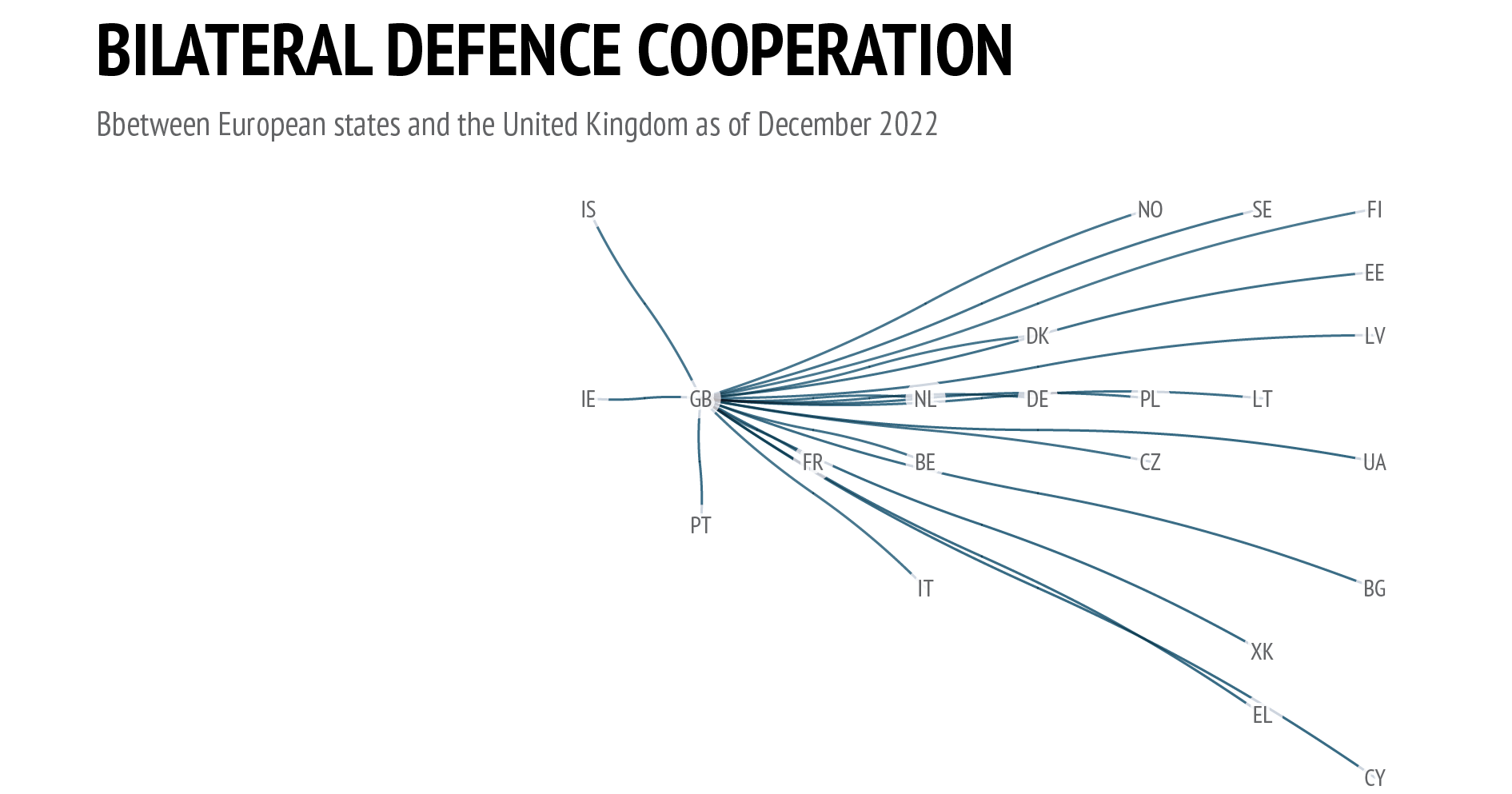

However, the lack of closer EU-UK defence cooperation is becoming increasingly awkward. The fact that the UK has been a leader in providing military support to Ukraine, maintains strong cooperation with almost all EU Member States bilaterally (as shown in the graphic on page 3), as well as in multilateral European defence cooperation formats, adds weight to arguments for a direct EU-UK dialogue (18). In fact, some defence cooperation, including the coordination of sanctions on Russia and weapons deliveries to Ukraine, has taken place. Furthermore, the UK was invited to join the EU PESCO project on Military Mobility in November 2022 (19).

To build on this progress, further participation of the United Kingdom in EU security and defence on an ad-hoc basis could be envisaged in other areas of mutual concern such as in the long-term support and training of the Ukrainian Army, societal resilience and defence research and capability development. To prepare for such cooperation, existing formats such as JEF and the Northern Group could provide venues for the EU to meet informally with the United Kingdom (and with partner countries Norway and Iceland) in back-to-back sessions, before any formal security and defence dialogue can be established.

UKRAINE

Ukraine is a priority partner and a candidate country to the EU since June 2022. As a candidate country at war with Russia, the EU is deeply committed to Ukraine’s survival and ability to fight. This includes massive financial support; sanctions on Russia; arms transfers by Member States partly funded by the EPF; and an EU military training mission.

Having accepted Ukraine as a candidate means that the EU will have to provide military support to Ukraine over the long term (20). The transfer of heavy modern western equipment such as Main Battle Tanks and advanced artillery is beginning but must be greatly scaled up. A further tailored EU defence partnership with Ukraine will not only have to include military assistance and training at an even larger scale, but also long-term provisions for rebuilding the defence industrial base and developing the future technologies and capabilities needed by Ukraine and the EU to face a hostile Russia in the years to come. Ukraine already has an Administrative Arrangement with the EDA since 2015 but which could be greatly expanded for these purposes. Also, invitations to selected PESCO projects could be considered.

STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP PLUS

NATO, the United States, Norway, Canada, the United Kingdom and Ukraine already cooperate on defence with the EU and its Member States quite extensively. Some suggestions on how to further tailor these partnerships have been outlined above. However, given the current grave security situation, elevating those partnerships to a ‘Strategic Partnership Plus’ format would be in the EU’s interest. Such a format would, however, need to be attractively and coherently designed, building upon the partners’ already significant contributions to European security and benefiting from shared threat perceptions. So, what might this look like?

Here, the ways in which the former WEU managed relations with its closest partners could serve as an inspiration. The WEU allowed non-EU, European NATO Allies to become ‘Associate Members’ who could join WEU missions and participate in some formal meetings and decision-making processes without voting rights (21). Following this model, the EU could consider creating a ‘Strategic Partnership Plus category’ for its closest partners.

However, a Strategic Partnership Plus format cannot be just another statement of intent but should reflect the importance the EU attributes to the respective partnerships in contrast to others. Accordingly, the few selected partners could be invited to regularly participate in the Political and Security US Committee and the Foreign Affairs Council, but without voting rights. Additionally, Administrative Arrangements with the EDA could be negotiated with close partners not already having one.

Norway, Canada and the United States can already contribute to CSDP missions and operations through their Framework Participation Agreements (FPAs), and all three have taken part in complex CSDP exercises on crisis management. (22) While cooperation with all those strategic partners is already quite extensive, further extending their access to appropriate EU decision-shaping on security and defence and collaboration on capability development should be discussed.

REGIONAL DEFENCE PARTNERSHIPS

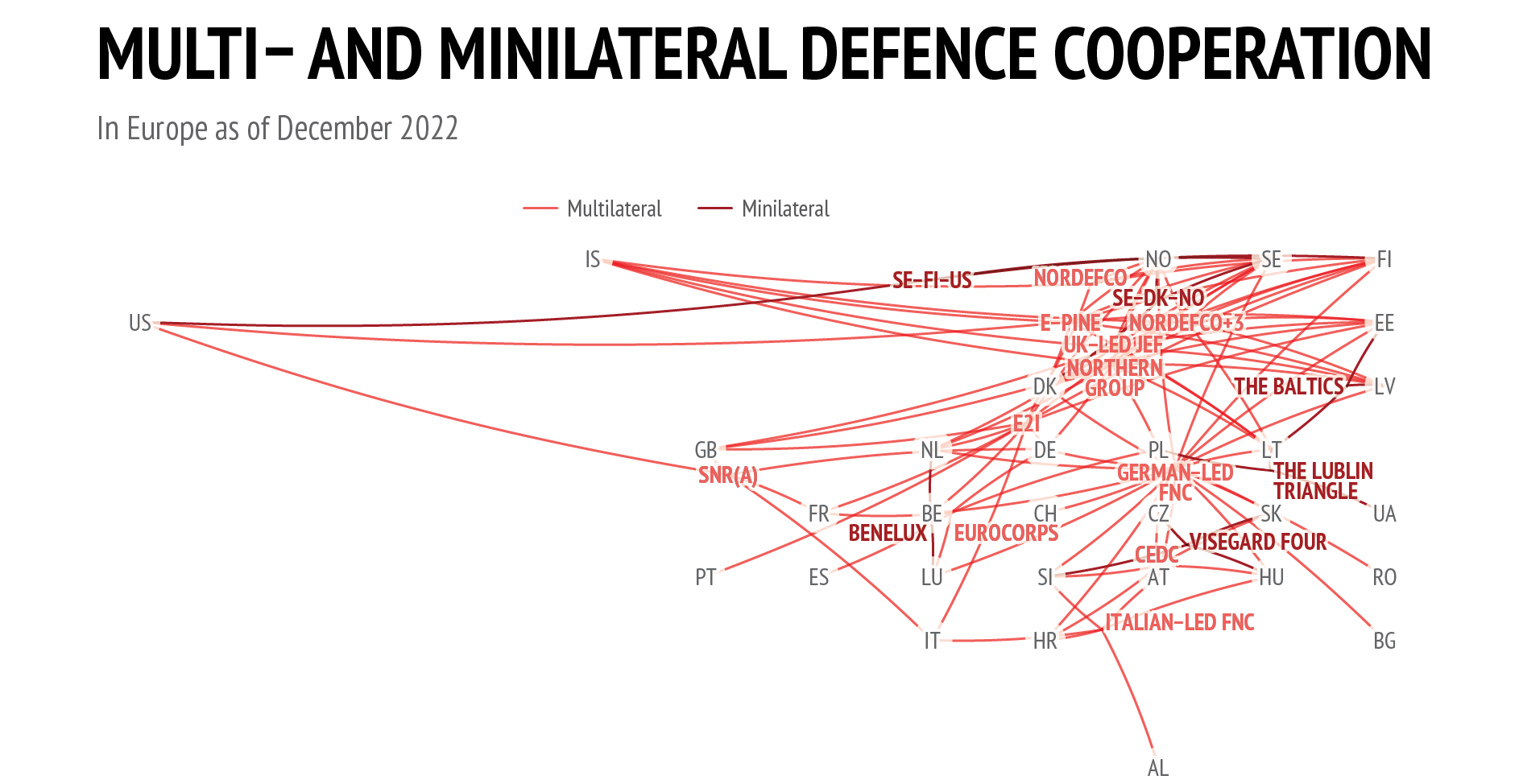

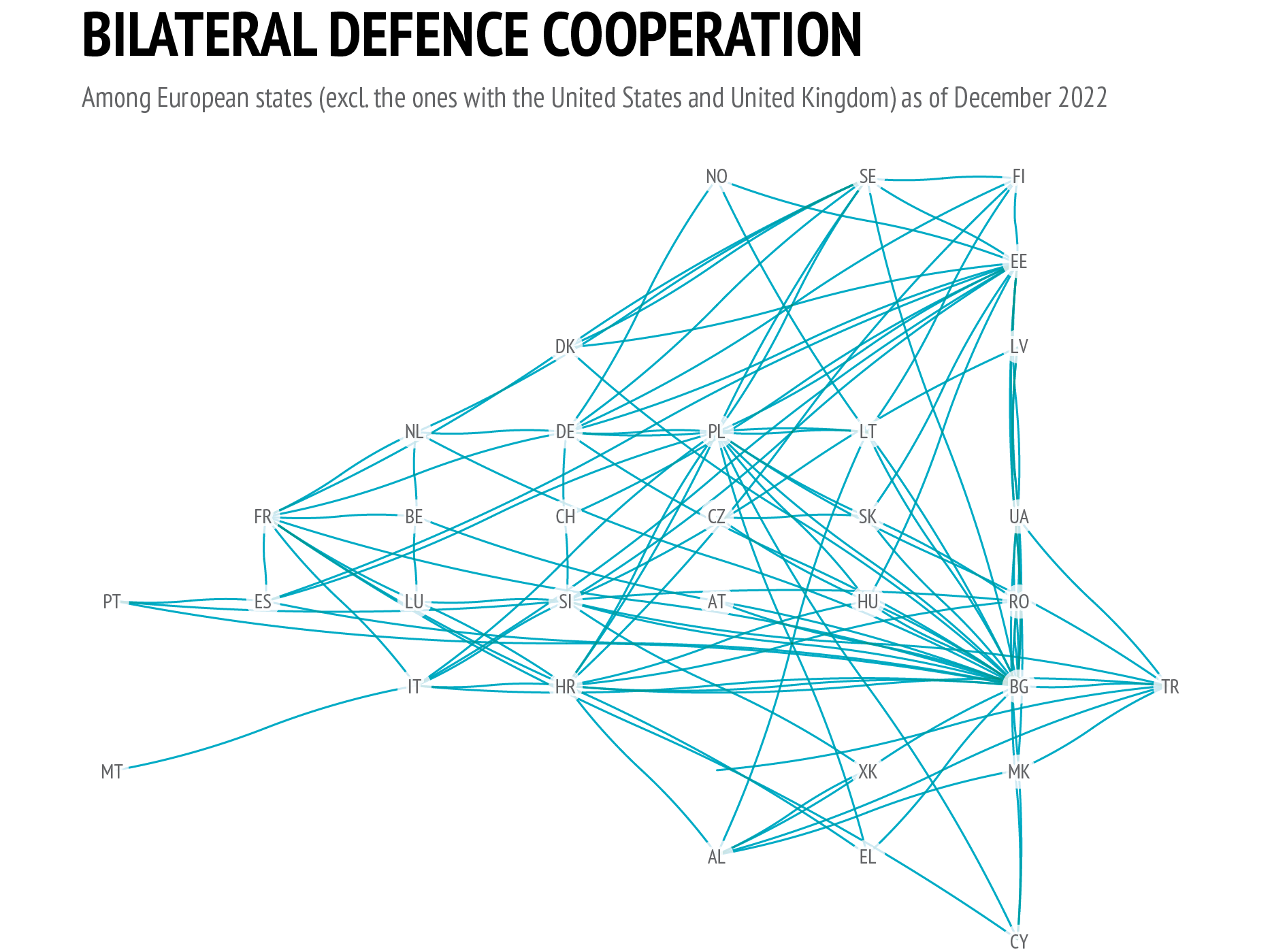

In addition to the EU and NATO, the European security architecture consists of numerous regional multilateral and bilateral defence cooperation formats, and for the purposes of this Brief, nearly 200 such defence partnerships have been mapped (23). In the graphic opposite, multilateral defence cooperation in Europe is illustrated and in the graphic overleaf on page 6, bilateral defence cooperation partnerships among European states are shown. Some of these formats are decades old, others very recent. Some are comprehensive and strategic in nature, while others focus on military branch-specific integration. Some are more regional or mission-oriented, and yet others are capability-focused with participating countries jointly building and/or acquiring new weapons systems. Almost all countries in Europe have bilateral and regional agreements with the United States.

MESSY SPAGHETTI OR WEB OF STEEL?

European defence cooperation consists of a myriad of multilateral and bilateral arrangements as well as capability-specific cooperation formats. A key question is whether this intricate architecture poses an obstacle to a more integrated European defence, or if it makes the overarching whole stronger. As illustrated in the graphic on page 7, are we looking at a bowl of messy spaghetti full of duplications and inefficiencies, or a web of steel providing the foundation for stronger European defence?

Given the many overlapping constellations, it may be tempting to argue for folding all defence cooperation into NATO or under the EU umbrella. However, each defence partnership builds on a different combination of driving factors. Some rely on geographical proximity or similar strategic cultures, and others have resulted from shared technological or industrial interests. While some partnerships are very traditional top-down general agreements, many European defence collaboration efforts are today bottom-up and demand-driven. For example, like-minded states cooperate in innovative ways to maintain key defence capabilities, ranging from cross-border training and common education to the pooling of spare parts and jointly operated air-to-air refuelling tankers (24).

Memberships often overlap. For example, there are bilateral and trilateral defence agreements between Finland and Sweden; between Finland, Sweden and Norway; between Norway, Sweden and Denmark; between Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden (NORDEFCO), which Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania sometimes join (NB8). All eight Nordic-Baltic countries are also part of the US-led Enhanced Partnership in Northern Europe (E-Pine) and the UK-led JEF with the Netherlands. All ten JEF-countries, in turn, join Germany and Poland in the informal Northern European Defence Policy Forum (Northern Group). All the Northern Group members except the UK are also members of the German-led 20-member Framework Nation Concept (FNC) construct. The Nordic countries (except Iceland) together with Estonia as well as the Netherlands, Germany and the UK are also part of the French-led European Intervention Initiative (EI2), in which Belgium, Italy, Portugal and Spain also participate. In addition, all countries mentioned have bilateral defence agreements with the United States.

Similar stories can be told in other parts of Europe. For example, in Central Europe there is bilateral defence cooperation between the Czech Republic and Slovakia; both cooperate with Hungary and Poland in the Visegrad Group (V4); all V4 countries are part of the Central European Defence Cooperation (CEDC) initiative, also involving Austria, Croatia and Slovenia. The latter three together with Hungary and Albania are part of the Italian-led Framework Nations Concept (FNC) cooperation mechanism. The seven countries in CEDC are all in the German-led FNC.

The most common form of European defence partnership is, however, bilateral. Some of these arrangements are rather empty of cooperation while others are extremely ambitious. In fact, many of the most successful partnerships are bilateral, a prime example of PT being the long-standing Belgian-Dutch integration of both countries’ respective surface fleets under a joint naval command.

Similarly, the 2010 Lancaster House treaties between France and the UK not only led to a Franco-British combined joint expeditionary task force but also to close collaboration on nuclear weapons issues.

The Netherlands and Germany are working very closely together, integrating their land forces, but also harmonising capability requirements, procedures, education and training. Similarly, close defence cooperation between Finland and Sweden includes operational defence planning, further cemented by their joint application for NATO membership.

Yet, some ambitious larger multilateral cooperation agreements exist as well. Given its focus on expeditionary capabilities in the Nordic-Baltic region, many analysts consider the JEF the most advanced Framework Nation Construct (25). Similarly, multilateral cooperation focused on system- or capability-specific strategic enablers that cannot be afforded or operated by individual countries has also proven successful. Here, the European Air Transport Command (EATC), where seven member nations pool and operate their military air transport assets under one single command, the Multinational Multi-Role Tanker and Transport Fleet (MMF) programme in which six countries jointly acquire and operate strategic tanker-transport aircraft, and the Strategic Airlift Command (SAC)/Heavy Airlift Wing (HAW) where 12 nations jointly own and operate strategic airlift together, are good examples (26). Another type of bottom-up, demand-driven defence collaboration can be found in user-groups of commonly used weapon systems in Europe, such as the Leopard 2 Main Battle Tank or the CV90 Infantry Fighting Vehicle, where participating Member States share first-hand experience of operating and maintaining the commonly held equipment (27).

LESS IS MORE

As the mapping shows, there is no shortage of European defence cooperation initiatives. While the Strategic Compass and other documents call for further strengthening European defence partnerships, coherence and quality of output should be prioritised over quantity of meetings. It is often said that EU Member States and NATO Allies only have one set of forces, but it is equally true that they only have one set of defence ministers and defence officials. Further proliferation of cooperation formats and meetings is arguably untenable and even counterproductive. The fragmented nature and slow pace of much defence cooperation also indicates that the lack of key European capabilities is not being adequately addressed. A major goal should be to focus on defence partnerships and cooperation formats that deliver value, and to reduce duplication and overlap. One proposal for improving efficiency and flexibility in European defence cooperation is to focus on outcomes in time-limited projects, rather than processes in open-ended partnerships, but also to ‘nest’ some cooperation formats hierarchically in the EU or NATO.

INSTITUTIONAL NESTING

Nesting refers to a situation in which one or more regional or issue-specific institutions exist within the framework of an overarching institution whose principles and norms (and often also rules and decision-making procedures) it shares, in a design similar to a set of Russian dolls, where one smaller doll fits inside a bigger one. Institutional nesting is thus a way to reconcile overlapping cooperation formats. In the case of trade, nesting occurs in the form of sector-specific international trade regimes that operate under the umbrella of the World Trade Organization (WTO)(28). In the case of defence, NATO’s FNC established at the Wales Summit in 2014 to develop deployable capabilities by multinational groups under a lead nation, is a good example. As JEF shows, the FNC enables countries that prefer working together to formalise and develop those relations but under NATO’s principles and norms. An example of a defence cooperation format nested in both NATO and the EU is perhaps the multinational EUROCORPS headquarters, which is linked with NATO’s command structure and the EU’s CSDP and stands at the disposal of both organisations.

In Northern Europe, all Nordic bilateral and trilateral cooperation formats could be nested inside NORDEFCO. With all Nordic countries soon to be NATO Allies, NORDEFCO itself could then be nested in the Alliance, resulting in an alignment of rules and decision-making procedures, as well as with NATO’s Defence Planning Process (NDPP). With Denmark joining CSDP and Norway and Iceland close partners of the EU, NORDEFCO could also facilitate Nordic coherence with EU-level priorities in the CDP and CARD, PESCO and the EDF. The fact that the recent defence ministers’ meetings between Finland, Norway and Sweden, as well as meetings of NORDEFCO, JEF and the Northern Group all took place back-to-back over two days in November 2022 indicates the striving for efficiency and the potential for nesting.

Capability-focused cooperation initiatives like the independent SAC and the MMF could also be institutionally nested. Both partnerships already rely on the NATO Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA) for support services but are not under NATO command. Given its close reliance on NSPA and the fact that Finland and Sweden will soon join the Alliance, the SAC could rather easily be nested in NATO, while the membership of the United States would make it difficult to nest it in the EU. In comparison, all the MMF nations are both NATO and EU Members and could more easily be nested in either organisation.

CONCLUSION

Today, European defence is built on cooperation between NATO and the EU, between the EU and its closest partners, as well on Member States’ bilateral and multilateral partnerships with each other and beyond the European continent. There is no shortage of European defence cooperation, but a stronger Europe in defence requires effective partnerships delivering real capabilities, and not additional summit declarations and photo opportunities. A major goal should therefore be to focus on partnerships and cooperation formats that deliver capabilities, while reducing duplication and overlap. The proliferation of meetings and working groups is untenable given that Member States and Allies operate with a single set of defence officials.

This Brief has first analysed EU defence cooperation with key partners and made suggestions for how these strategic partnerships might be further tailored and enhanced. Granting some of the closest partners more privileged access to select EU instruments and decision-making fora in a ‘Strategic Partnership Plus’ format could provide incentives for even deeper and more effective cooperation. The Brief has also focused on European multilateral and bilateral defence cooperation. Given the very large number of existing cooperation formats, the concept of ‘institutional nesting’ emerges as a way to reconcile the many overlapping formats. Hierarchically nesting some cooperation formats in others that all share overarching principles and norms would reduce overlap and ‘meeting fatigue’, increase efficiency, coherence and output of remaining European defence partnerships, and ultimately lead to a Europe that is ‘stronger together’.

No comments:

Post a Comment