The Challenges of United Front Work

The evolution and escalation of China’s overseas influence in recent years has captured the attention of foreign policy elites across the world. In October 2022, news broke of the discovery of three secret police stations run by the Chinese government in London and Glasgow. It was revealed these stations were being used to repatriate overseas Chinese, monitor those classified by the Communist Party of China (CPC) as political dissidents, as well as counteract social movements in the UK deemed ‘anti-China’.[1] A report by the Spanish civil rights group Safeguard Defenders confirmed the existence of such stations in at least 21 countries across five continents since 2018.[2] A few months prior in January 2022, MI5 had issued an unprecedented alert detailing Chinese United Front Work Department official Christine Lee’s targeted donations of £420,000 to UK parliamentarians of strategic interest to Beijing, including Sir Ed Davey and Barry Gardiner.[3]

The evolution and escalation of China’s overseas influence in recent years has captured the attention of foreign policy elites across the world. In October 2022, news broke of the discovery of three secret police stations run by the Chinese government in London and Glasgow. It was revealed these stations were being used to repatriate overseas Chinese, monitor those classified by the Communist Party of China (CPC) as political dissidents, as well as counteract social movements in the UK deemed ‘anti-China’.[1] A report by the Spanish civil rights group Safeguard Defenders confirmed the existence of such stations in at least 21 countries across five continents since 2018.[2] A few months prior in January 2022, MI5 had issued an unprecedented alert detailing Chinese United Front Work Department official Christine Lee’s targeted donations of £420,000 to UK parliamentarians of strategic interest to Beijing, including Sir Ed Davey and Barry Gardiner.[3]Such activities are not unique to the UK. They are commonplace in countries with high overseas Chinese populations and robust economic exchanges with China. This is due to Xi Jinping’s revival of united front work (tongyi zhanxian gongzuo 统一战线工作), a strategy of propaganda, alliance-building, and espionage that has undergirded his administration’s foreign policy in recent years. Historically, the CPC employed united front tactics to bring certain individuals and groups within Chinese society into the Party’s fold, and ultimately establish moral and ideological leadership across China. In 1942, united front work became a set of domestic governance practices institutionalised in the creation of the United Front Work Department. Under Xi, modern-day united front work tactics have been elevated from a domestic governance approach to a foreign policy strategy which targets the civil societies, governments, and economic operations of other countries.[4] This foreign policy strategy has received unparalleled institutional support granted under Xi’s 2018 reforms, including the creation of four new bureaus responsible for ‘overseas Chinese affairs’ as well as the United Front Work Department’s absorption of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office and the State Administration for Religious Affairs.[5] According to analysts, these institutional reforms effectively subordinated China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the United Front Work Department.[6] Modern day united front work operates on the principle of the ‘three warfares’ (san zhan 三战): public opinion warfare (yulun zhan 舆论战), psychological warfare (xinli zhan 心理战), and legal warfare (falü zhan 法律战).[7] Experts have struggled to categorise united front work as either ‘hybrid warfare,’ ‘soft power,’or ‘sharp power,’ because it involves a wide range of activities from espionage to cultural diplomacy. Nevertheless, these activities all aim to influence the domestic environments of countries overseas in ways that favour the advancement of CPC objectives.[8]

Specifically, united front efforts can include but are not limited to: (a) disinformation and pro-CPC propaganda campaigns, (b) substantial donations to influential individuals and groups that hold favourable views of China, © discouraging Chinese diaspora from supporting political dissidents or anti-CPC movements, (d) mobilising pro-China groups to silence criticism of the CPC, and (e) reducing the impact of the ‘Taiwan democratic model’ overseas.[9]

Compared to authoritarian systems, democracies are especially vulnerable to these activities; their commitments to freedom of speech and freedom of press usually entail looser regulations on civil society activities and the flow of information. The traditional dichotomy drawn between civil society and the military spheres within democratic systems has also undermined efforts to identify united front work.

This dichotomy has caused policy makers to view united front work as simply a security issue as opposed to a society-wide phenomenon requiring cooperation and coordination between civil society and the organs of national security. This presents fertile ground for disinformation and propaganda to take root among targeted social groups, which can stoke distrust in democratic elites, institutions, and processes.

Many countries experiencing united front work within their borders presently lack the institutional means to identify and counter these interference activities, highlighting the urgent need for research on institutions that effectively resist it at the levels of national security and civil society.

Taiwan is arguably the country with the richest experience and greatest institutional capacity in terms of resisting united front work. During the Chinese Civil War from 1927 to 1949, the CPC developed united front tactics to co-opt groups within Chinese society into alliances with the Communists against the rival Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, hereafter ‘KMT’ or ‘Nationalists’) vying for political and military control over China. After losing the civil war, the Nationalists relocated their government to Taiwan to in 1949.[10] Since then, China and Taiwan have maintained separate political, legal, and economic systems. Since the 1970s, Beijing has used united front work to advance the goal of China’s unification with Taiwan. CPC propaganda campaigns have sought to influence the Taiwanese public to support peaceful unification with China, to identify more as ‘Chinese’ than ‘Taiwanese,’ as well as empower groups within Taiwanese society and politics that favour unification with China. However, despite these efforts, approximately 90% of the country’s population identify exclusively as ‘Taiwanese’ as opposed to ‘Taiwanese and Chinese’ or ‘Chinese,’[11] and a vast majority of Taiwanese oppose unification with China.[12] Alongside the strong consensus among Taiwanese that Taiwan and China are separate states, Taiwan has also become more entrenched in its commitment to democratic norms and values since its transition from authoritarianism to democracy in the 1990s. Today Taiwan is widely considered one of the leading democracies in Asia, consistently achieving high scores in the RSF Freedom of Press Index and Freedom House’s Freedom in the World country reports. As a democracy with decades-long experience at the forefront of resisting Chinese interference, the case of Taiwan offers valuable lessons for other democratic nations facing united front activities within their borders.

As Taiwan’s counter-interference institutions have played a crucial role in its resistance to united front efforts, they are worth further examination. One of the institutions at the forefront of countering united front work is Taiwan’s political warfare system (zhengzhan zhidu 政戰制度). Drawing lessons from the loss of mainland China in the civil war, KMT elites believed the main factor contributing to their defeat was a lack of political unity and ideological conviction within the party. In other words, where the Nationalists had failed to win over the Chinese population to their cause, the CPC had succeeded in persuading diverse groups of people of the appeal of Marxist-Leninist ideology and the Communist’s superior leadership.

So effective was united front work propaganda that it even convinced several high-ranking KMT commanders to defect to the CPC during the civil war. Seeking to address the lack of ideological unity within the Nationalist’s ranks, party leader Chiang Kai-shek established the political warfare system in Taiwan in the 1950s.

The political warfare system became crucial to fostering a strategic culture, defined as a common set of ideas regarding strategy that exist across a population, within the Taiwanese military and society that has arguably contributed to the country’s effective resistance towards united front work today.[13]

‘Political Work’ and the Origins of Taiwan’s Political Warfare System

To understand the political warfare system and its approach to countering united front work in the modern era, it is essential to briefly examine its historical origins. The precursor to the political warfare system was the political commissar system, an institutional model geared toward the ideological instruction of a state’s military that was imported from the Soviet Union by both the Nationalists (KMT) and Communists (CPC) during the 1920s.[14] The political commissar system runs parallel to the structure of the military and has two main functions: to provide education in political values to military personnel and monitor the political loyalties of troops, ensuring they did not deviate from the party.[15] In 1924, in an effort to unite the country and eliminate the chaos brought about by provincial warlords competing for territorial control over China, the KMT and CPC forces established the first ‘united front’ with support from the Soviet Union. That same year, the Huangpu Military Academy was founded by the KMT with the support and guidance of Soviet Union officials to train troops from both the Nationalist and Communist forces in military strategy as well as the ideology of party founder Sun-Yat Sen.[16] In 1926, Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-Shek led a purge against the Communists which resulted in the dissolution of the united front between the two parties and the start of the Chinese Civil War. The political commissar systems of the KMT and CPC, once interconnected under the first united front, were separated that same year.[17] In 1927, KMT elites discovered the CPC was targeting Huangpu Military Academy trainees with propaganda which sought to dissuade them from supporting the Nationalists due to widespread corruption within the party.[18] Communist propaganda was so effective it resulted in widespread defection from the KMT to the CPC. Nationalist and Taiwanese military elites to this day view the experience at Huangpu Military Academy as a ‘historical lesson’,[19] and consider this episode the prototype for the modern political warfare system — evidenced by the prevalence of slogans like ‘Huangpu spirit’ (huangbu jingshen 黃埔精神) in the institution today.[20]

The origins of political warfare lie in the concept of ‘political work’ (zhenggong 政 工), a practice employed by both the Nationalists and Communists which sought to strengthen ideological commitment to the party. Chiang Ching-kuo, son of Chiang Kai-shek and former president (1978–1988), described the significance of political work in the following way: ‘Revolutionary spirit flourishes most when political work is most developed. Military spirit falls when political work declines.’[21] It is clear political work was seen by the KMT as a tool for consolidating unity and boosting morale among troops. Chiang’s conceptualisation of political work is strongly linked with Sun Yat-Sen’s ‘political tutelage’ (zhengxun 訓政), a stage within Sun’s envisioned path to eventually establishing constitutional democracy where the party educates citizens in an effort to instill loyalty to the KMT and fundamental values within society. These values included fostering nationalism, democracy, and citizens’ livelihood under Sun’s ‘Three Principles of the People’ (sanmin zhuyi 三民主義). Nationalist elites believed would create the necessary environment for constitutional democracy to be introduced. In the years following the KMT’s loss of control over China to the CPC and retreat to Taiwan, the Nationalist leadership was most preoccupied with ensuring the military’s ideological loyalty through political work. Political work was seen as the antidote to the defection and espionage activities that had unfolded in Huangpu Military Academy at the onset of the Chinese Civil War. The task of political work was not only to impart KMT values to the military but also to foster a quasi-nationalistic political loyalty toward the party. During the early martial law era, political work was carried out with the aim of reinvigorating troops’ morale to one day fight against the Communists and regain control of China.

As the KMT implemented political work within the military, an initial conceptualisation of ‘political warfare’ began to emerge. Chiang Kai-shek described political warfare as a ‘battle of wits’ (douzhi 鬥知) in contrast to warfare on the battlefield as a ‘battle for power’ (douli 鬥力). In the 1956 Joint Operations Framework (lianhe zuozhan gangyao 聯合作戰綱要), Chiang built on the ideational focus of political warfare in the ‘30% military and 70% politics’ principle (sanfen junshi, qifen zhengzhi 三分軍事, 七分政治). The ‘70% politics’ referred to organisational warfare (zuzhi zhan 組織戰), political warfare (zhengzhi zhan 政治戰) social warfare (shehui zhan 社會戰), strategic warfare (moulüe zhan 謀略戰), psychological warfare (xinli zhan 心理戰), propaganda warfare (xuanchuan zhan 宣傳戰), sabotage warfare (pohuai zhan 破壞戰), and intelligence warfare (qingbao zhan 情報戰).[22]

Chiang’s principle sought to articulate the link between the ideational or psychological elements of war — societal awareness of enemy tactics, persuasion, morale — with its more material components, such as running military drills or the procurement and maintenance of weapons systems. However, as the political warfare curriculum developed over the course of the martial law era, the concept evolved to encompass six more distinct categories of warfare: psychological warfare (xinli zhan 心理戰), ideological warfare (sixiang zhan 思想戰), organisational warfare (zuzhi zhan 組織戰), intelligence warfare (qingbao zhan 情報戰), strategic warfare (moulüe zhan 謀略戰), and mass warfare (qunzhong zhan 群眾戰). These are known as the ‘six warfares’ (liu zhan 六戰) and are the basis from which Taiwan’s political warfare system trains political warfare officers in counter-interference today.

Psychological warfare is defined as the ‘extra-military skill’ of defeating the enemy through spiritual determination (jingshen yizhi 精神意志), using strategy as guidance, ideology as a foundation, intelligence as a reference point. In practice this means attacking the weak points of the enemy’s ideology. Unlike psychological warfare, which focuses on the enemy or threat, ideological warfare involves establishing a coherent and unified ideology within the military and among civilians. Organisational warfare refers to establishing counter-interference organisations, coordinating their operations, generating plans with strategic goals, as well as synthesising the broader counter-interference strategy at the levels of politics, economy, culture, and society. Intelligence warfare is the practice of accumulating as much knowledge as possible about the enemy and developing warfare tactics from the basis of ‘knowing oneself and knowing the enemy.’ Strategic warfare involves consolidating the enforcement of policy at the military and political levels, differentiating united front activities according to the political, economic, psychological, and military spheres, as well as introducing confusion and chaos in the enemy implementing their strategy. Finally, mass warfare refers to integrating civil society’s role within warfare, mobilising and leading civilians during wartime, and removing any obstacles to military-civilian cooperation.[23] Overall, the two core values the political warfare system seeks to impart to soldiers and civilians are: 1) for whom do we fight? (weishei erzhan 為誰而戰), 2) for what do we fight? (weihe erzhan 為何而戰).[24] Figure 1 synthesises the political warfare system’s incorporation and operationalisation of the six warfares:

Figure 1

Figure 1The Evolution of the Political Warfare System from Martial Law to Democratisation

The modern-day structure and operations of the political warfare system are informed by Taiwan’s not-too-distant authoritarian past. A number of political warfare officers I interviewed argued that democratisation strengthened Taiwan’s political warfare system due to improved capacities for ‘soft warfare’ (ruanzhan 軟戰).[25] Others have claimed the system functioned best in an authoritarian context, but at the expense of citizens’ privacy and liberties.[26] However, this paper seeks neither to assess the effectiveness of the political warfare system in the pre- or post-democracy periods nor to evaluate whether the political warfare system is democratic or undemocratic. Rather, I argue that tracing the evolution of the political warfare system will provide a deeper understanding of how the institution has since been reconfigured to operate in a democratic context.

During the martial law era, Taiwan’s political system could be characterised as ‘rule by party’ (yidangzhiguo 以黨治國). This meant the party, military, and administrative offices of government were highly fused, with the party taking precedence over the operations of the other organs of state. The military, including the political warfare system, therefore remained ‘party-fied’ (danghua 黨化). As the KMT’s ideology was rooted in the ‘Principles of the Three People’ which included Sun Yat-Sen Thought (guofu sixiang 國父思想), this defined the party’s ideological education of political warfare officers. Sun Yat-Sen Thought emphasised the values of democracy (minzhu 民主), human rights (renquan 人權), legal systems (fazhi 法制), freedom (ziyou 自由). Historically Sun Yat-Sen Thought was viewed as the rival ideology to Communism and contrasting vision for uniting China during the Chinese Civil War. Over the decades following the KMT’s retreat to China in the 1940s and 50s, the Nationalists, still concerned with regaining territorial control over China, sought to revive Sun Yat-Sen Thought in its psychological warfare strategy towards Chinese citizens. Psychological warfare consisted of counter-propaganda campaigns which encouraged the Chinese public to question the CPC’s leadership and support the Nationalist regime in Taiwan which promised greater freedoms and rights to citizens in Sun Yat-Sen’s envisioned path to constitutional democracy.[27]

Inspired by the US military, the KMT’s ideological education within the political warfare system emphasised cultivating patriotism, dedication to Sun Yat-Sen Thought, and loyalty to party elites under its ‘leadership programme’ (lingxiu gangling 領袖綱領). Taiwan’s Garrison Command (jingbei zongbu 警備總部) was the institution at the forefront of implementing Sun Yat-sen’s ‘political tutelage’ phase towards the military and society.[28] Under political tutelage, the political warfare system was not only responsible for monitoring the political beliefs of military officers but also Taiwanese citizens, which involved reading citizens’ private correspondence to ‘protect secrets and guard against espionage’ (baomi fangdie 保密防諜). Such activities were part and parcel of Taiwan’s party organisation (dangzu黨組) structure which, much like the CPC’s danwei (单位) system, established a party representative at most levels of civil society to exert political control. However, since Taiwan’s democratisation, the presence of the party organisation system within civil society has been entirely dismantled. Accordingly, the political warfare system no longer monitors private correspondence and the institution’s ‘monitoring’ (jiancha 監察) operations have been reformed to focus solely on military personnel.[29]

During the martial law era, China’s united front propaganda towards Taiwan emphasised mutual recognition between Chinese and Taiwanese, encouraged Taiwanese to identify as Chinese, and sought to advance the misleading narrative of Taiwan as a ‘breakaway province’ that must return to China. In response, Taiwan’s political warfare work was characterised by a strategy of ‘stabilising the interior, disrupting the exterior’ (annei raowai 安內繞外). For political warfare officers, stabilisation of the interior meant ensuring loyalty to the commander within each battalion, as well as ensuring the military strategy (junshi zhanlüe 軍事戰略) — building the military’s defence capabilities — and national strategy (guojia zhanlüe 國家戰略) — the ‘grand strategy’ of how the state combats warfare at the legal, military, and economic levels — were well-coordinated.[30] On the other hand, disruption of the exterior was characterised by two activities: 1) persuading the Chinese public of the merits of Sun Yat-Sen Thought, which emphasised citizens’ fundamental rights and the path of constitutional democracy in contrast to the CPC’s authoritarianism, 2) encouraging people in China to question CPC leadership and ideology. Slogans such as ‘The Three Principles of the People unifies China’ (sanmin zhuyi tongyi zhongguo 三民主義統一中國) were seen as an alternative, counterpropaganda to China’s pro-unification discourse, the content of which included promoting the phenomenon of ‘anti-Communist righteous surrender’ (fangong yizhi touxiang 反共義士投誠) as well as highlighting the superiority of Sun Yat-Sen’s Three Principles of the People (sanmin zhuyi 三民主義) vis-a-vis Communist ideology (gongchan zhuyi 共產主義). The Political Warfare System’s News Bureau and the Liu Shao Kang Office (liushaokang bangongshi 劉少康辦公室) were the primary institutions responsible for disseminating this counterpropaganda during the martial law era.[31] The Liu Shao Kang Office disseminated this propaganda through radio channels, banners on ships sailing through the Taiwan Strait, streamers from aircrafts, and other such means during the 1980s.[32]

However, following on the heels of Taiwan’s democratisation in the 1990s, the political warfare system was extensively reformed under a programme called ‘nationalisation of the military’ (jundui guojiahua 軍隊國家化). Nationalisation of the military meant ideologically and institutionally decoupling the party from the military. In the political warfare system, this involved reconfiguring the education of troops to train loyalty to the Republic of China (ROC) government and constitution as opposed to a single political party or individual. Nationalisation of the military was also characterised by a concerted effort to ensure greater ‘administrative neutrality’ (xingzheng zhongli 行政中立) among all military personnel. At a legislative level, this was enshrined in articles 5 and 6 of Taiwan’s National Defence Act, which state: ‘the ROC infantry, navy, and air forces should serve the Constitution, be loyal to the nation, love the people, bear the utmost responsibility, to protect national security,’and ‘the ROC infantry, navy, and air forces surpass individual, regional, and party ties, relying on the law to maintain political neutrality.’[33]

To implement this legislation, political warfare officers were barred from participating in any political events or publicly promoting their political views. The recruitment of political warfare officers was expanded to include more social groups beyond the KMT’s usual support base such as women and aboriginal peoples. Ideological education was gradually reformed to foster troops’ loyalty to the government and constitution, no matter the political party in power.[34] This meant less emphasis on Sun Yat-Sen Thought and the Three Principles of the People and an increased focus on learning the articles of the constitution relating to national defence. Decoupling the KMT from the military was also reflected in reforming the powers of appointment within Taiwan’s broader national defence system. For example, former president Chen Shui-bian (2000–2008) transferred the power of appointing the most senior position within Taiwan’s political warfare system from the president to the Ministry of Defence. The move was considered another important step towards ensuring greater administrative neutrality as it reduced the likelihood of politically motivated appointments made by the leader of the ruling party. The separation between the organs of the party and military was further underscored by the change of position’s title from ‘Chief of Defence’ (canmou zongzhang 參謀總長) to ‘Chief of National Defence’ (guofangbu canmou zongzhang 國防部參謀總長).[35]

However, the decoupling of the KMT from the military and the implementation of administrative neutrality within the political warfare system has taken several years and for some remains an on-going process. Many senior political warfare officers who were trained prior to the nationalisation of Taiwan’s military in the late 90s and early 2000s tend to favour the KMT politically. But as the political warfare system’s recruitment has broadened to include more women, aboriginal peoples, and people from Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ‘green’ regions, the make-up of the system and its ideological leanings appear to be moving closer towards the ideal of administrative neutrality.

Since democratisation, the counter-propaganda activities towards Chinese citizens as well as the surveillance of Taiwanese citizens’ political loyalties that were characteristic of the political warfare system under martial law have either ceased entirely or been extensively reformed in greater compliance with democratic norms and values. During the phase of political tutelage under martial law, the operations of ‘monitoring’ and ‘ideological education’ were directed towards both military personnel as well as civilians. The KMT elite considered this a necessary step in fostering a political environment in which constitutional democracy could eventually be realised. Following Taiwan’s democratic transition over the 90s, these functions of the political warfare system have largely been redirected towards the training of political warfare officers. Nevertheless, some vestiges of this authoritarian institutional legacy continue to inform the modern-day operations of the political warfare system. These institutional legacies will be further explored in the next section.

The Modern-day Operations and Structure of Taiwan’s Political Warfare System

The operations of the political warfare system can be categorised according to nine areas: political warfare (zhengzhan 政戰), propaganda/communications (wenxuan 文宣), monitoring (jiancha 監察), defence (baofang 保防), psychological warfare (xinzhan 心戰), counselling (xinfu 心輔), support for retired officers (juanfu 眷服), media (xinwen 新聞), civilian affairs (minshi 民事). Drawing from the works of several Taiwanese scholars of political warfare as well as several interviews with political warfare officers, the table below explains each component of the political warfare system as well as its practical applications:

Table 1

Table 1These categories and activities within the political warfare system are often overlapping and highly interconnected. For example, defence education of high school students falling under the category of ‘civilian affairs’ work may also involve utilising propaganda to highlight the effectiveness of the Taiwanese military response to China’s interference attempts and intimidation tactics. All-out defence education may then also contribute to the defence component of Taiwan’s political warfare system by increasing social awareness of the manifestations of China’s united front work and therefore reduce the likelihood of espionage activity. For example, Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defence hosts an ‘All-Out Defence Summer Camp’ which educates Taiwanese youths about the concept and operations of national defence: from counter-interference to providing support to other civilians in wartime scenarios.[40] These kinds of educational programmes have also featured trips to Taiwanese-controlled islands in the South China Sea, such as Itu Aba (Taiping) and Pratas (Dongsha), where political warfare officers detail Chinese military activity and Taiwanese responses.[41] Other activities falling under ‘All-out Defence Education’ and ‘civilian affairs’ work could involve dispatching political warfare personnel for administrative assistance to organisations like local temples,[42] which are commonly a target of Chinese united front activities.[43]

Some of the operations carried out by Taiwan’s political warfare system are still informed by its authoritarian past. For example, ideological education remains a fundamental component of modern political warfare training. These ideological education sessions require military personnel on a weekly basis to watch programmes like ‘Chuguang Island Garden’ (juguang yuandi 莒光園地) which educates soldiers in interference and counter-interference operations, such as the ‘three warfares’ approach underpinning China’s united front work, manifestations of united front work or CPC espionage, and other related topics. After watching this programme, trainees are then required to record their views on this ideological education material in diaries (dabing riji 大兵日記) which are then submitted to a political warfare officer for review.[44] If trainees exhibit thoughts or behaviours deemed ‘problematic’ or ‘risky’ for the operations of the political warfare system, such as mental illness, ‘anti-establishment thinking’, strong connections with the CPC, or excessive fixation on financial gain, they will either undergo further ideological education or be removed from the military.[45] The ideological education and monitoring components of the modern-day political warfare system are therefore continuations of the institutional practices during the martial law era.

Though many of the operations within these nine branches are largely concentrated within Taiwan’s military, there remains a high level of interaction and exchange between the political warfare system and civilians. This is in part because the political warfare system educates groups within Taiwanese society, including students and public service workers, about military operations and interference activities from China. This pedagogical function of the political warfare system is implemented through ‘all out defence education’ (quanmin guofang jiaoyu 全民國防教育) as well as ‘military classes’ (junshi ke 軍事課) taught in Taiwanese high schools and universities.[46] Furthermore, due to the policy of mandatory military service, most members of the Taiwanese public will receive a basic education in the ideology and operations of the political warfare system. Therefore, the political warfare system’s impact extends well beyond the military by fostering a strategic culture within civil society that contributes to the strength of Taiwanese resistance to united front work.

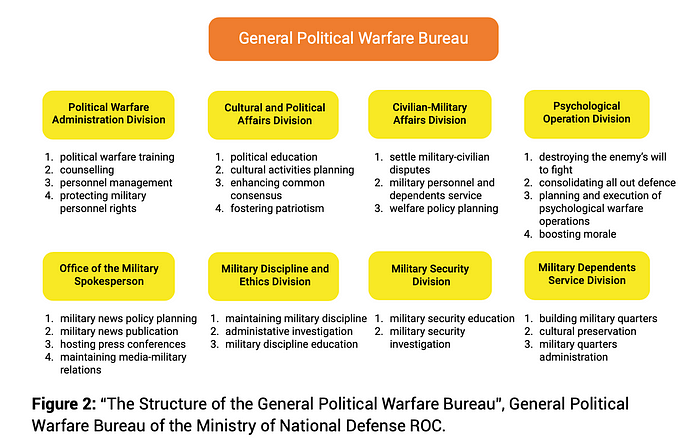

In terms of structure, the General Political Warfare Bureau (guofangbu zhengzhi zuozhanju 國防部政治作戰局) is the central institution of the political warfare system. The GPWB is comprised of eight divisions, each dedicated to operationalising the nine areas of political warfare:

Figure 2

Figure 2As Figure 2 demonstrates, several divisions within the GPWB coordinate with civilians to implement political warfare within Taiwanese society. The Psychological Operation Division is involved in delivering all-out defence education and bolstering public morale in the event of war. The Civilian-Military Affairs Division is responsible for resolving military-civilian disputes such as noise disturbances caused by military traffic zones situated near residential areas. The Military Spokesperson’s Office works with the Taiwanese mainstream media to deliver military-related news as well as identify fake news of cross-Strait military activity. The ways in which the GPWB divisions work with civil society is crucial to understanding the country’s relative success in resisting united front work campaigns and is an area that would benefit from further research.

The political warfare system is one institution within Taiwan’s broader national defence structure alongside the National Security Bureau (guojia anquanju國家安全局), Investigation Bureau (diaochaju 調查局), Ministry of the Interior National Policy Agency (neizhengbu jingzhengshu 內政部警政署), Coast Guard Administration Ocean Affairs Council (haiyang weiyuanhui xunshu 海洋委員會海巡署), and the Military Police Command (xianbin silingbu 憲兵司令部).[47] The majority of personnel within all of these institutions will have received training in political warfare. Within the broader national defence structure, the political warfare system works most closely with the National Security Bureau and the Investigation Bureau on countering espionage activity within Taiwan. The directors from the GPWB and National Security Bureau meet monthly to exchange intelligence and discuss how to counteract China’s united front work activities.[48] The GPWB and National Security Department also coordinate with the Ministry of Education to implement ‘all-out defence education’ across high schools and universities.[49] In recent years as disinformation campaigns have intensified, the GPWB has worked with the Fact Checking Centre (shishi chahe zhongxin 實查核中心), a cabinet-level department responsible for monitoring fake news on Taiwanese social media outlets, to identify and counter any disinformation relating to cross-Strait military activities. For example, following former US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022, a deep fake picture of Chinese naval warship off the Taiwanese mainland coast was widely circulated on Taiwanese social media outlets. The Fact Checking Centre worked with the GPWB and Ministry of National Defense to alert the public of this fake news through all official military webpages and accounts.[50] These examples highlight the ways in which Taiwan’s counter-interference strategy is highly interconnected and coordinated across areas of policy relating to both national defence as well as civilian affairs.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

The hybrid nature of united front work — a strategy of interference that employs both military and non-military tactics — presents substantial challenges for democratic countries which boast freedom of speech, freedom of press, and vibrant, diverse civil societies. United front work capitalises on the looser state control over civil society characteristic of many democracies as well as the lack of social awareness around the nature of CPC interference. This is evident in the number of pro-CPC organisations and societies linked to united front work institutions that exist across many democratic countries, as well as the increase in disinformation campaigns during events of political significance such as elections or referendums. Under Xi Jinping, united front work has become more institutionally robust and intertwined with China’s foreign policy than ever before. Repelling united front work activities therefore necessitates the institutionalisation of counter-interference and the coordination of counter-interference operations at the levels of national security and civil society.

Though its institutional character is informed by an authoritarian past, Taiwan’s political warfare system nevertheless presents interesting lessons in counter- interference for democracies. These lessons are even more pertinent when one considers how this once authoritarian institution has been reconfigured to not only to better conform to Taiwan’s democratic norms, values, and processes but also protect those features from foreign interference activities that would seek to exploit these features. Overall, this briefing has sought to highlight how the political warfare system has contributed to Taiwan’s ability to effectively resist united front work.

Through its educational role, the political warfare system strengthens counter- interference abilities in two ways: 1) exposing united front work and the ideology motivating these activities, 2) spreading awareness of united front work activity across the military and civil society. Many countries have been confounded in their attempts to identify united front work due to its hybrid and varied nature, which ranges from targeted political donations and espionage activity to the establishment of pro-CPC cultural organisations. Therefore, Taiwan’s political warfare system can be seen as an instructive case in how democracies can institutionalise the education of the military and civilian populations in foreign interference. If the public is more able to identify instances of foreign interference like disinformation, it will likely mitigate the effect of these activities and therefore improve a country’s ability to resist interference in the first place.

The political warfare system also assists in coordinating counter-interference efforts across Taiwan’s civil society and national defence architecture. Within Taiwan’s defence architecture, there is a high level of exchange and cooperation between the local and national level institutions–from the police to the investigation bureaus and national security organs–in identifying activities associated with united front work. The political warfare system contributes to this coordination not only by providing fundamental training to all personnel in united front work tactics but also through monthly briefings on united front activity with other organs of national defence. These regular cross-institutional exchanges can provide insight for other countries in terms of synthesising the identification and repellence of united front work.

Based on these findings, I posit the following policy recommendations for improving democratic resistance against united front work through a ‘whole-of- society’ response:Defining foreign interference in legislation and incorporating this definition into the frameworks of relevant state institutions.

Introducing education in foreign interference activity into the national curriculum.

Creating accessible educational programmes and or tools that improve public media literacy, public understanding of how foreign interference operates in the digital sphere as well as public knowledge of civic duties and democratic procedures.

Training all military personnel as well as staff within relevant state institutions in the nature of foreign interference as well as the implementation of a broader counter-interference strategy.

Establishing a chain of command between a centralised Fact-Checking Centre and the organs of state and national defence to identify and publicise any instances of foreign interference through social media.

Establishing a platform for greater coordination and cooperation between civil society groups and state institutions in reporting instances of espionage or foreign interference.

No comments:

Post a Comment